When It Comes to Reporting Deaths of Incarcerated People, Most States Break the Law

Our team at the University of North Carolina analyzed death-in-custody reporting policies at every state and federal carceral entity. Data collection is a mess—and many states don’t follow the law at all.

Death reporting in prisons has become even more opaque in 2022. For more than 20 years, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) at the Department of Justice (DOJ) has collected data on deaths of incarcerated people under its Mortality in Correctional Institutions program (MCI). The MCI, created in response to the Death in Custody Reporting Act (DCRA) of 2000, has been criticized for years as inadequate and toothless. Nearly every state seems to comply with the law differently—and many do not comply at all.

But in spring 2021, the BJS quietly announced it was terminating that data collecting entirely. Since reporting runs roughly one year behind, this means that December 2021’s report on the 2019 calendar year will be the last.

Our team analyzed department of corrections policies that should align with the DCRA, which Congress reauthorized in 2014, and found that most correctional institutions do not maintain such protocols. There is reason to believe the law is not being followed. To address these problems, we suggest that data on deaths in custody should be managed by an independent agency housed outside the DOJ, and that when jurisdictions fail to adhere to the law, they should be penalized with grant-funding cuts.

The Origins of the Federal Death in Custody Act

The DCRA was designed to provide oversight of carceral record-keeping. The legislation arose after reporters began investigating and publicizing the excessive number of custodial deaths in the 1990s. Perhaps most notably, Mike Masterson, then an investigative reporter with the Asbury Park Press in New Jersey, estimated in 1995 that more than 1,000 people had died in jails across the country over a four-month period. Masterson then traveled to Washington, D.C., to distribute copies of his report directly to lawmakers. The first version of the DCRA passed five years later in 2000.

The law requires state and federal law enforcement agencies to report deaths that occur in prisons and jails, or in police custody, to the U.S. Attorney General’s office every three months. In addition, the DCRA mandates that law enforcement agencies collect data on the circumstances surrounding an individual’s death in custody as well as their demographic information, including gender, race, ethnicity, and age.

States that fail to share this information can lose up to 10 percent of their funding under the Edward Byrne Justice Assistance Grant Program, one of the main programs by which the federal government subsidizes state and local law enforcement agencies. Importantly, however, there appears to be no evidence that any state has ever been penalized for failing to comply with the DCRA.

Mortality in Correctional Institutions Reports

These reports are the only reports detailing deaths in custody nationally. However, the publication of these statistics lags behind the data collection; the most recent Mortality in State and Federal Prisons data available to the public is from 2019.

Further, past reporting has raised questions about the quality of the data itself. For example, a 2018 report by the Office of the Inspector General found that not all federal law enforcement agencies were submitting reports. The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), for example, does not currently publish data reports on deaths of people in federal custody. As for state prisons, the DOJ decided that the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) would collect data for the department starting with the first quarter of fiscal year 2020. Carceral entities would report death information from their respective facilities on a quarterly basis to a centralized state agency that would collate and submit the information to BJA in compliance with federal law.

When asked for comment on the future of MCI data collection, BJS Public Affairs Specialist Tannyr Watkins referred The Appeal to the DCRA’s list of Frequently Asked Questions but did not provide comment on the sunsetting of the dataset. The agency did not say whether it plans to publish data collected from carceral agencies.

An Analysis of Death-Reporting Policies

We explored death-investigation procedures and reporting policies among correctional departments by reviewing the operational guidelines at 50 state prison systems, the District of Columbia Department of Corrections, the BOP, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). We supplemented our analysis with information from state and federal records obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests. In addition to policies on public reporting, we evaluated procedural obligations dictating whether correctional facilities must contact a medical examiner/coroner upon an individual’s death and whether obtaining an autopsy is necessary in all instances.

Our main objective was to understand how states report mortality information to higher authorities. Additionally, we surveyed reports and press releases from departments of corrections to understand how systems share mortality data on public-facing websites.

Most States Do Not Follow the Rules Set Forth in the DCRA

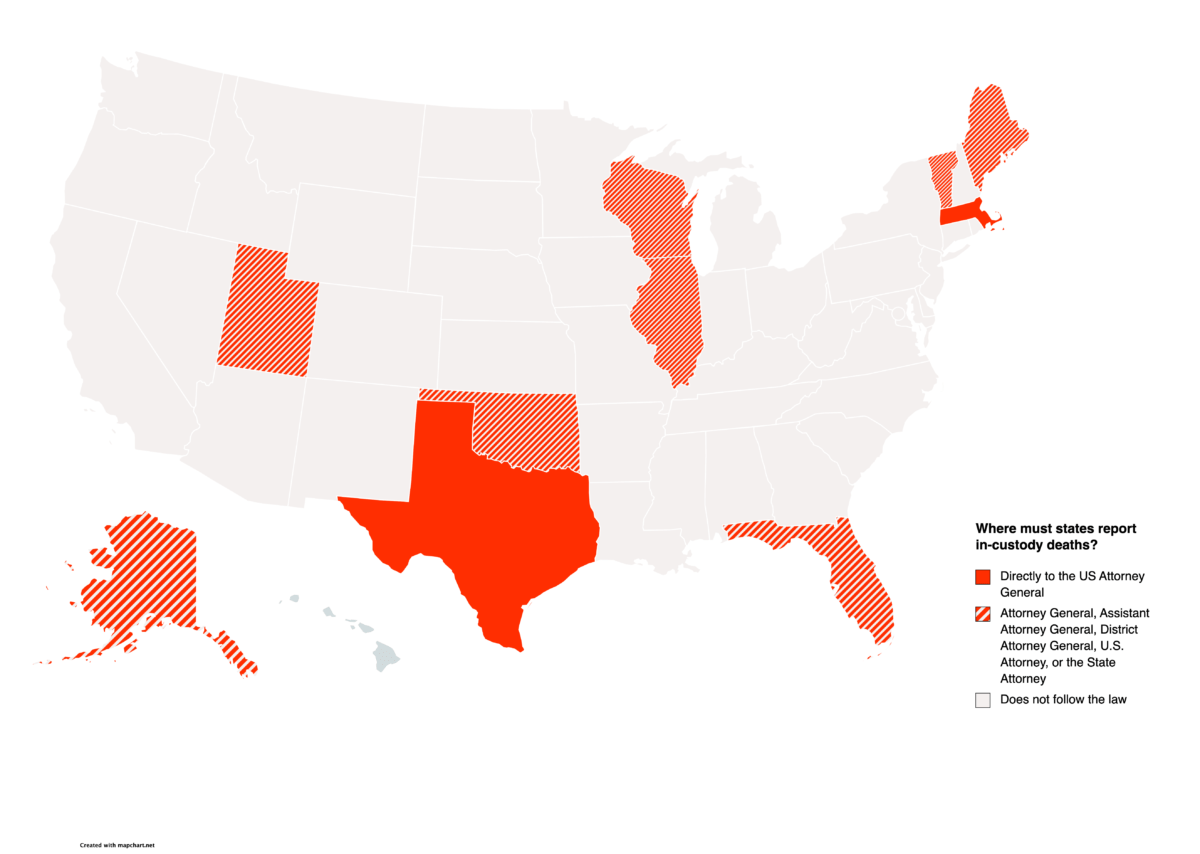

We found that internal policies on death reporting vary substantially across prison systems. Only 15 states mandate the reporting of deaths to courts or prosecutors. Of those 15 systems, just two (the Massachusetts Department of Correction and the Texas Department of Criminal Justice) require correctional facilities to report in-custody deaths directly to the U.S. Attorney General and the DOJ.

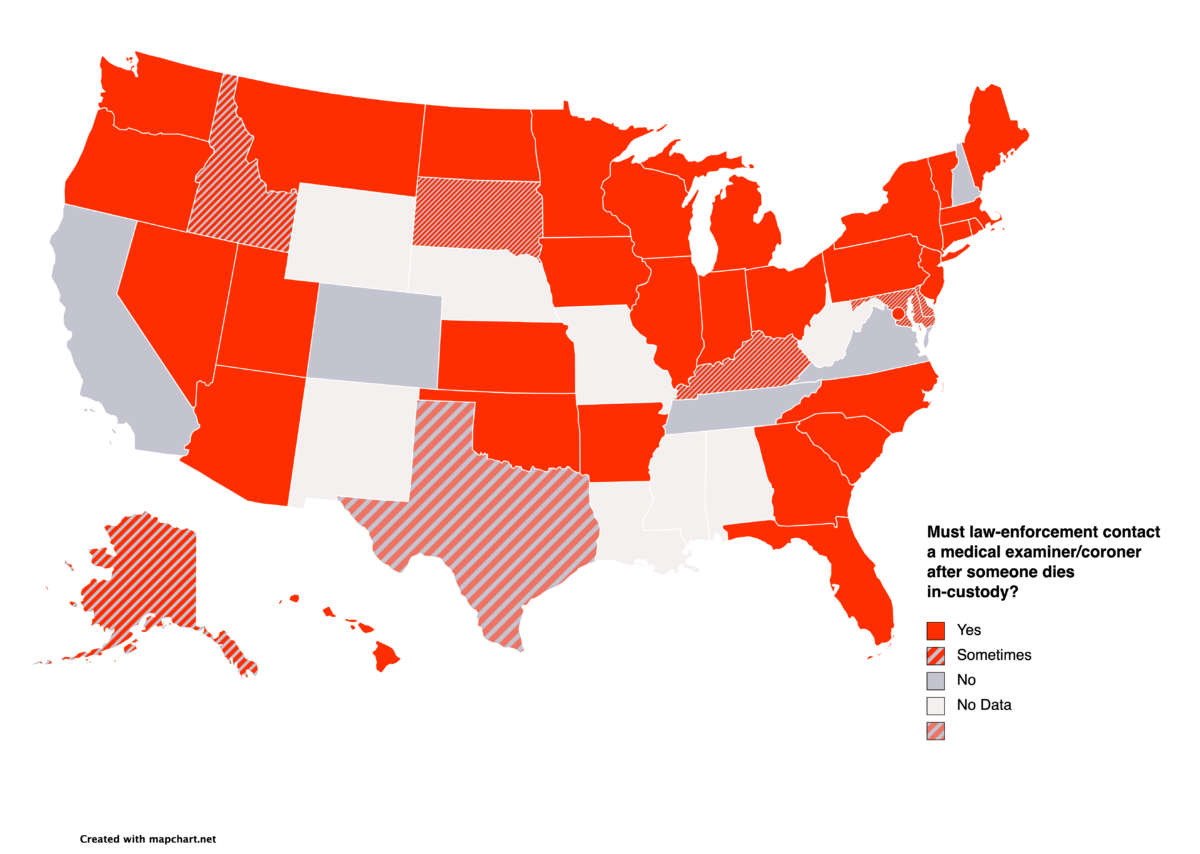

We found that 38 prison systems maintain policies consistent with state requirements that frequently require notification of a medical examiner or coroner in response to the death of an individual in custody. However, of these jurisdictions, only 31 require this contact for all instances of death. Just eight systems explicitly require that an autopsy be conducted, with two (ICE and the Arizona Department of Corrections) mandating this for all death. While the absence of compliant policies does not inherently mean an agency is violating the law, neither does it allow for a degree of transparency aligned with the seriousness and finality of death.

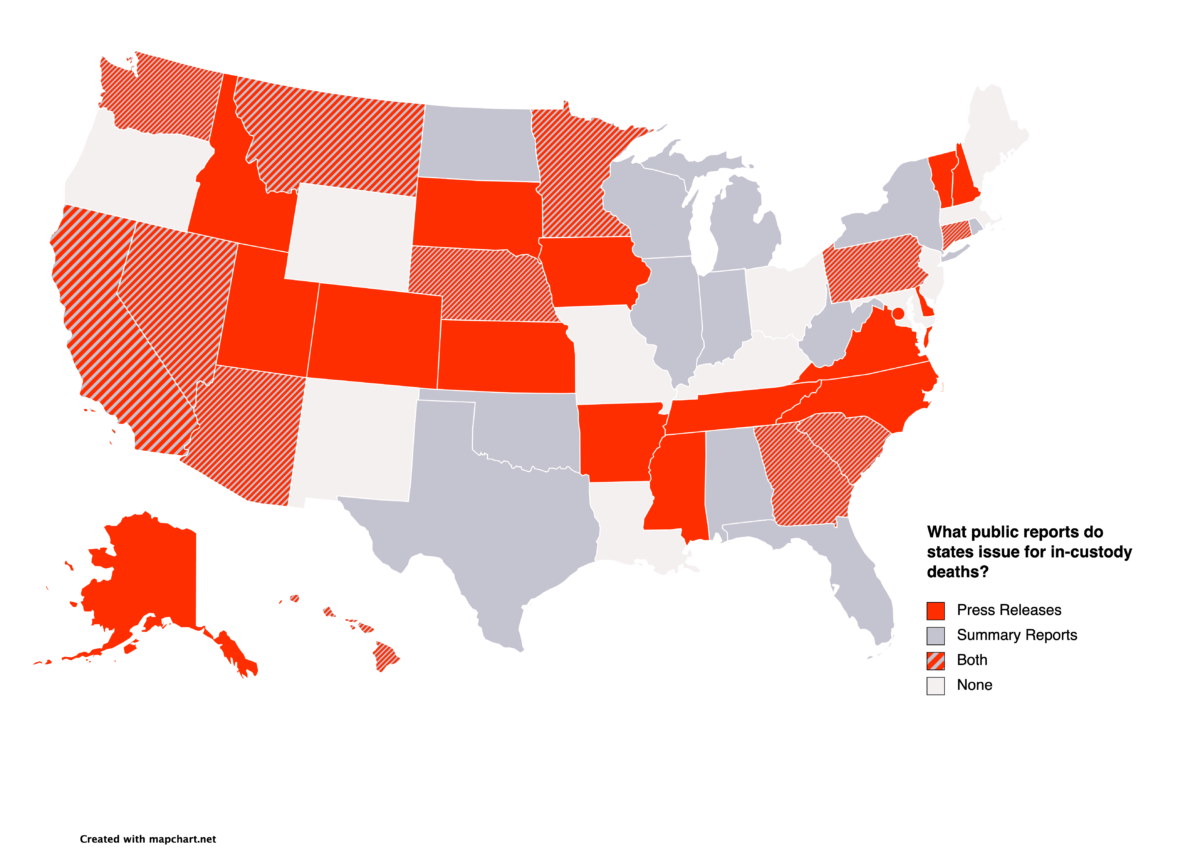

Thirty-six systems provide some public disclosure of the number of deaths in custody (e.g., through statistical reports or press releases). However, the content and breadth of the reports vary widely. In addition, reports do not always list causes of death—eight systems reported a number of deaths with no such information. Many states do not record the race of those who die while in prison custody, a key variable in understanding the role of incarceration in worsening health inequities. Twenty-eight systems issue press releases when an incarcerated person dies. Still, the frequency of press releases in states such as Louisiana, Mississippi, and Montana did not match the number of deaths reported in statistical publications.

Our Recommendations

The failure of many states to standardize reporting protocols means that prison systems may inaccurately estimate deaths of incarcerated people in their custody. Available mortality data is neither transparent nor timely. This lack of information hampers public health efforts to respond to deaths in real time. Failing to provide current data on mortality also creates additional barriers to combating communicable diseases in carceral settings, such as COVID-19.

Government leaders require such data to make informed decisions about deploying resources to protect the health and well-being of both incarcerated people and members of the public. The absence of demographic-linked mortality data also obscures health inequities of overrepresented communities in carceral populations.

Incarceration worsens health, shortens life expectancy, and exacerbates preexisting medical conditions. Mortality data linked to race, ethnicity, national origin, gender, disability, and religion is crucial to understanding how incarceration heightens health inequities. Confronting these disparities requires data on health outcomes disaggregated by key demographics.

In the absence of accurate, timely, and transparent data, academia has responded with creative, interdisciplinary research methods. For example, students under the tutelage of Professor Andrea Armstrong at the Loyola University New Orleans, College of Law have worked to identify previously unreported in-custody deaths in Louisiana parish jails through records requests.

Similarly, the University of North Carolina’s Third City Project, led by founder and principal investigator Dr. Lauren Brinkley-Rubinstein, uses cause-of-death information to uncover hidden health disparities across U.S. prisons.

And yet, such an essential government function should not be the responsibility of researchers alone. Ideally, an independent agency housed outside the DOJ would manage the reporting of deaths in custody. Monitors could, among other things, draft model policies for corrections departments so they can adopt minimum reporting standards. One way to achieve this is to make in-custody deaths a “notifiable condition”—that is, a type of disease or cause of death of which authorities must legally be notified. In a December 2015 piece in the academic journal PLOS Medicine, a team of Harvard University researchers argued that these types of accountability and oversight structures could be applied to police killings and law enforcement agencies more broadly.

Jurisdictions that fail to adhere to the law should be penalized with grant-funding cuts. Financial consequences for noncompliance are necessary to achieve meaningful reforms in mortality-data transparency. Most importantly—given the growing acknowledgment that policing and incarceration adversely impact individual and public health—funding should perhaps be redirected from law enforcement agencies to public health programs designed to curb mortality and prevent incarceration. Specifically, dollars can be reinvested in communities that represent people who are dually affected by disparities in health and targeted by the criminal legal system. Thus, holding law enforcement agencies responsible for violating the DCRA is a solution that is simultaneously obvious, feasible, and without precedent.