Support Independent Journalism. Donate today!

President Biden has pardoned thousands of people for cannabis-related offenses. But to truly give people “second chances,” he should push congress to erase peoples’ marijuana-related criminal records entirely.

Death row prisoners rarely get last meals, writes Lyle May, who is on death row in North Carolina. But on the night of an execution, the prison staff break room is full of cookies and cake.

In total, 44 states lack universal air conditioning requirements in their prisons. A new federal program called the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund could help catalyze action.

A suit filed this week accuses Broome County Jail staff of using threats of punishment to “create a culture of fear” that forces pretrial detainees to submit to unpaid labor.

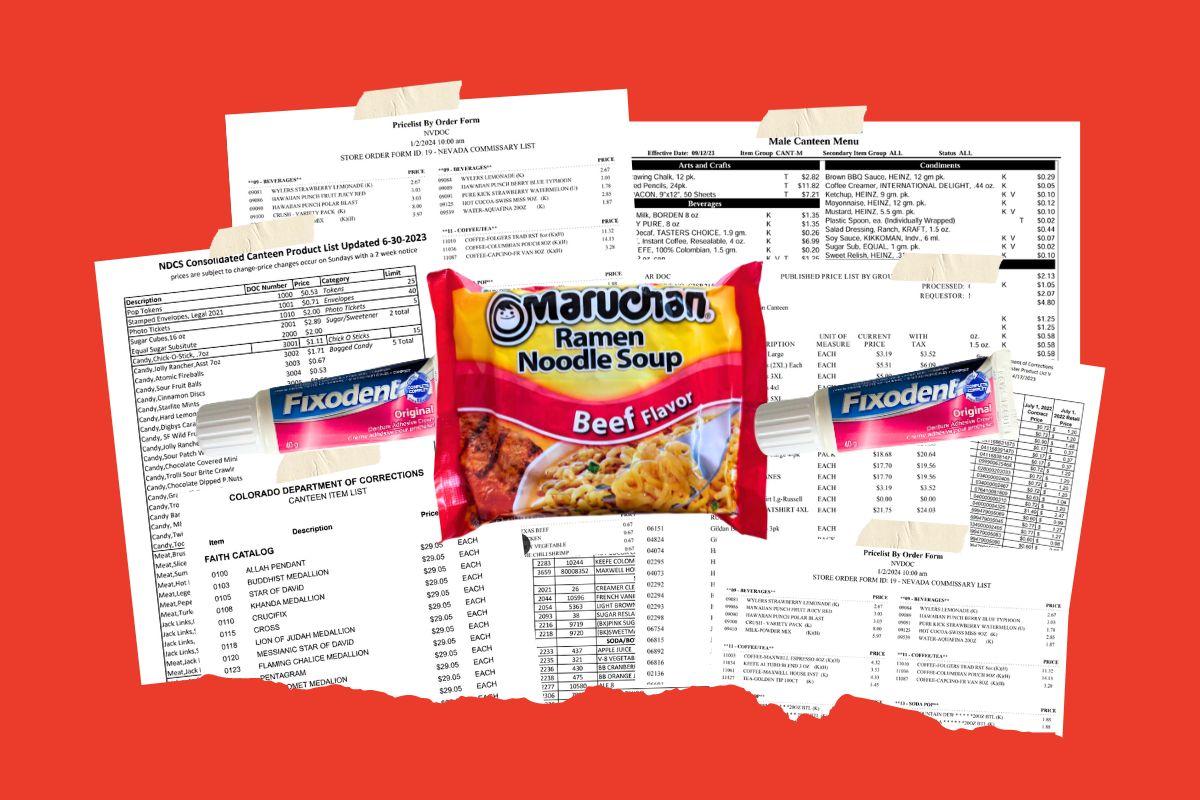

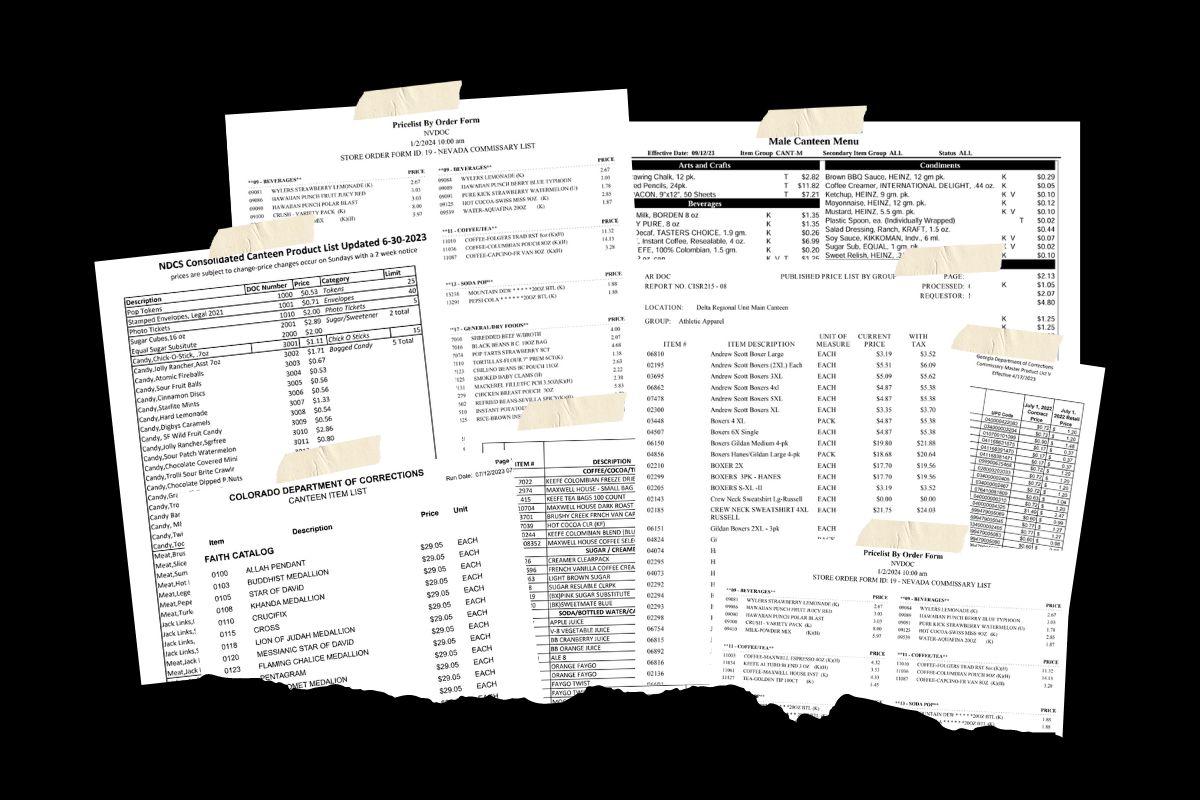

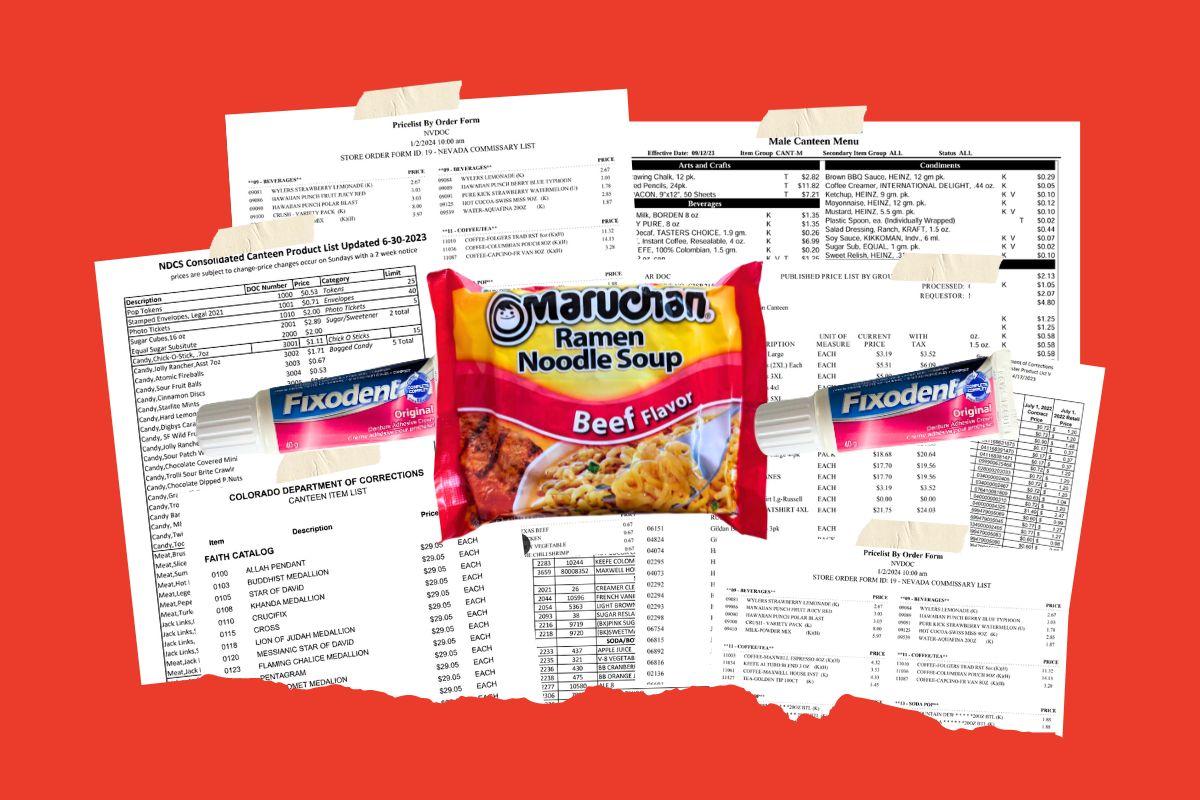

Inside The Appeal’s 9-month investigation.

The Appeal’s 9-month investigation uncovered prison commissaries’ exploitative, inconsistent systems with inside prices up to five times higher than in the community and markups as high as 600 percent.

At Kentucky’s Northpoint Training Center, incarcerated people are not allowed to participate in programs until they’re at least four years away from their parole board date—robbing people of years of educational opportunities.

Incarcerated people have testified before state lawmakers about legislation that would directly impact their lives, including bills to change the cost of prison communications and rein in extreme sentencing practices and the use of solitary confinement.

The Arizona Supreme Court ruled that the state can enforce a near-total abortion ban from 1864. The ban allows no abortions except to save the life of a pregnant person and carries a mandatory two- to five-year prison sentence for people who provide abortions.

Lawmakers tried and failed to track “wandering officers.” But state regulators also refuse to release data that would help journalists and the public do so.

On the hook to repay $1.3 billion of debt this year, the nation’s largest prison telecom company, Securus, is on the verge of bankruptcy. Its failure would represent a remarkable victory for advocates—and a potential beginning of the end for the industry as we know it.

The federal Bureau of Prisons has suggested banning imprisoned people from using social media—but First Amendment defenders say the rule would chill free speech and silence whistleblowers.

A report by the Vera Institute of Justice and Black & Pink highlights the many ways in which state prisons mistreat transgender people—nearly 90 percent of respondents said they’d been placed in solitary at some point.

Free prison tablet programs rely on predatory contracts with juggernauts of prison industry, Aventiv and Global Tel Link.

“That video visitation is going to work,” one Genesee County official reportedly said in 2012. “A lot of people are going to swipe that Mastercard and visit their grandkids.”

Larry Jones says Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputy Ira Ynigo crushed his middle finger in a door and, instead of helping him, locked the door and walked away. “He watched me scream,” Jones said.

A former youth social worker reckons with her involvement in an institution that often does irreparable harm to the children it is supposed to help.

The ACLU sued the state after it moved children to the former death row unit at the notorious Angola prison. But a court filing says the kids have faced abuse in their new facility, too.

The U.S. Department of Justice is investigating the Phoenix Police Department for potential civil rights violations. During last week’s city council meeting, residents said city officials must stop fighting the inquiry.

A recent report by the New Jersey Comptroller’s office found that a company called Street Cop trained police to shoot indiscriminately at people, medically experiment on the injured, and treat virtually anyone who isn’t a white, straight, cisgender male with open disdain. More training like this won’t make America safer.

New York officials have flooded the subway system with cops and military personnel in a show of “security theater.” Will it actually make people safer—and is that even the point?

The teacher was disciplined after refusing a supervisor’s orders to tell students literacy tests weren’t racist and instead meant to ensure people “knew what they were voting for,” according to the lawsuit.

My husband Nick died from COVID-19 in March 2020 while imprisoned pretrial. Joe Biden has said he’d help others like him before it’s too late. But so far, the president has yet to make good on his promises.

BOP Director Colette Peters blamed understaffing and “crumbling” facilities for the increasing number of deaths in federal prisons during hearings last week.

Five public defenders are running for seats on the Los Angeles Superior Court. Tomorrow, voters will decide whether to elect candidates who support alternatives to incarceration—or maintain the status quo.

Multiple legal groups on Monday filed a lawsuit to protect Pennsylvanians from being thrown in solitary for extended periods of time, or if they have mental illness.

Sens. Elizabeth Warren, Ed Markey, and Jeff Merkley wrote a letter to the federal Bureau of Prisons and Department of Justice asking the agencies not to renew a contract with the American Correctional Association.

I realized that I had fallen victim to one of white supremacy’s greatest weapons: the war on imagination.

The ACLU says the state’s policy is the “most restrictive” in the nation.

The Thirteenth Amendment bans all “badges and incidents” of slavery. But the use of police dogs enacts cruelty on both people of color and the dogs themselves. To fully rid society of slavery, the dogs must be retired.

According to (admittedly flawed) FBI data, the U.S. is about as safe as it’s ever been. So why is tough-on-crime rhetoric on the rise?

On Jan. 19, New York City Mayor Eric Adams vetoed a bill that would have effectively banned solitary confinement in his city’s jails. Incarcerated writer Chris Blackwell and CUNY Law Professor Deborah Zalesne share why the practice is so horrific.

State Sen. Anna Hernandez filed the bill following The Appeal’s investigation into the Phoenix Police Department’s shooting of Jacob Harris. Though police killed Harris, his friends were charged using the state’s felony murder statute. Tomorrow, a coalition will join Hernandez in a press conference to support the bill.

The bill requires people be held on bail for dozens of new, small-time charges—and virtually eliminates charitable bail funds after nonprofits posted bonds for many anti-Cop City protesters last year. Gov. Brian Kemp is expected to sign the measure into law.

A small unit inside the Omaha Police Department helps to handle the deluge of mental health crises that police grapple with daily.

In 2001, a jury found Terence Richardson and Ferrone Claiborne not guilty of murdering a police officer. But, thanks to a 1996 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, a judge sentenced both men to life in prison anyway. Yesterday, the Supreme Court of Virginia granted Richardson a new hearing to prove his innocence.

A federal complaint filed today alleges that the Ronald McDonald House is discriminating against people with sick children who happen to have been convicted of certain crimes in the past. The ACLU, among other groups, alleges the rule violates the federal Fair Housing Act.

Late last year, the U.S. Department of Justice warned the state of Tennessee that its “aggravated prostitution” statute—which makes it a felony to engage in sex work while HIV positive—violates the Americans with Disabilities Act. Activists hope the measure shows how the government can use the ADA to fight ableism around the nation.

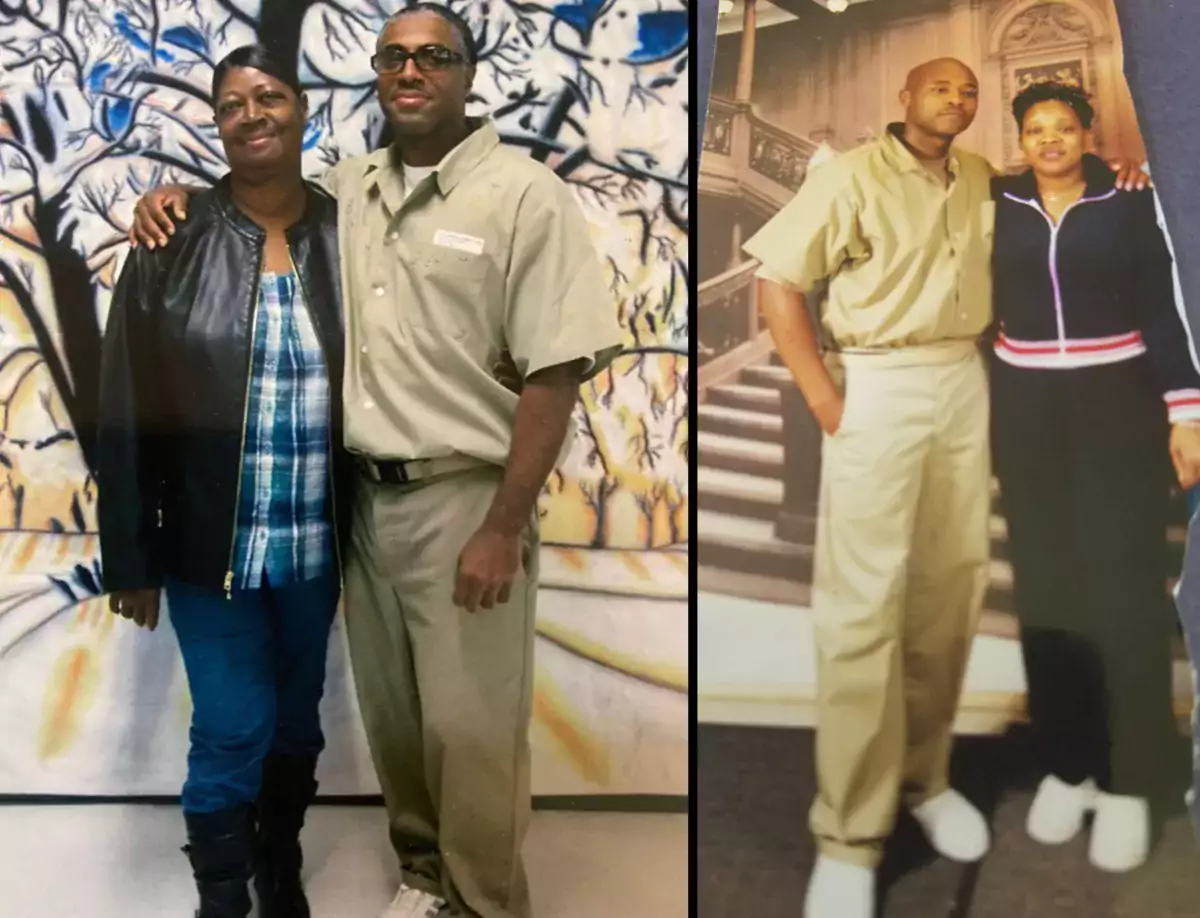

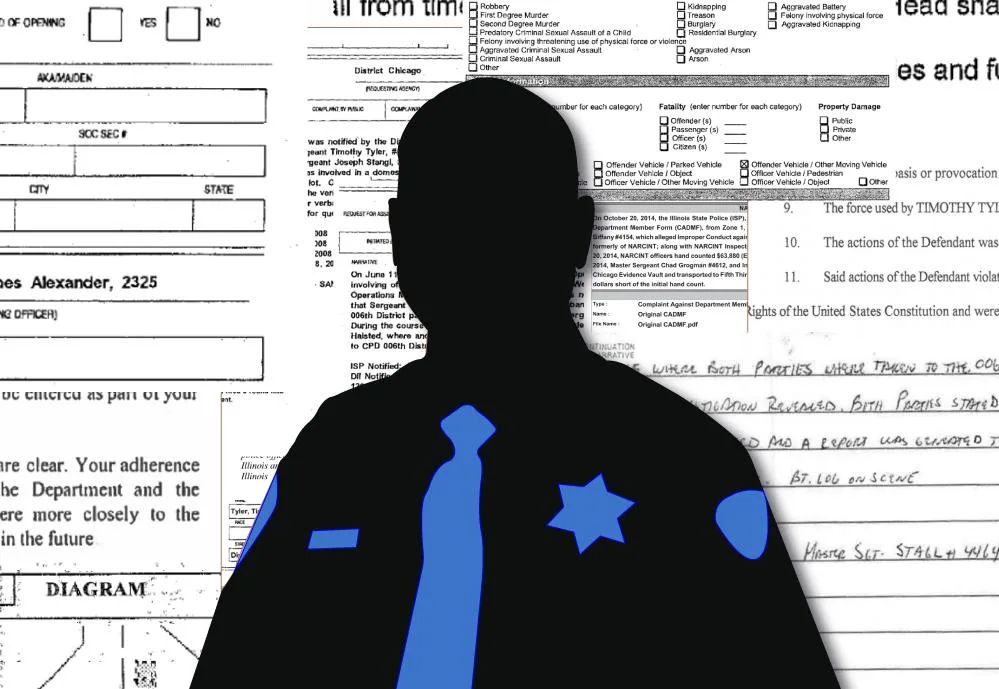

In 2022, Timothy Tyler was chosen to lead the Champaign Police Department — despite a string of misconduct allegations from his first policing job in the south Chicago suburb of Markham through his time at the Illinois State Police.

The department reported misses more than 550 times in 2023, and a public safety director complained about a 55-round miss in 2022.