Commentary

Ask The Appeal: Why Do Americans Think the U.S. is Too ‘Soft’ on Crime?

According to (admittedly flawed) FBI data, the U.S. is about as safe as it’s ever been. So why is tough-on-crime rhetoric on the rise?

Welcome to “Ask the Appeal,” the first in an ongoing series of pieces in which we answer common questions about the criminal legal system—and how it intersects with everyday life. For our inaugural piece, Appeal Research & Projects Editor Ethan Corey breaks down why, despite plummeting crime rates, tough-on-crime policies seem poised for a comeback. Have a question you’d like to ask? Email tips@theappeal.org with the subject line “Ask the Appeal” today.

According to a Gallup poll released in November, for the first time in 20 years, the majority of Americans think the U.S. is “not tough enough” on crime. In a marked shift from the last time Gallup asked this question, 58 percent of respondents said they believe the criminal-legal system is too soft, up from 41 percent in 2020.

This change in public opinion coincides with growing fears about—allegedly—rising crime in the United States. In the 2022 midterms, most voters ranked violent crime among their top issues. And in late 2020, a Gallup poll found that perceptions of increased crime reached their highest levels since 1993.

A few years earlier, “tough on crime” policies seemed passé. In major cities, voters elected pro-reform prosecutors who ran on promises to reduce the use of cash bail and end prosecutions of low-level misdemeanors. Deep-red states like Oklahoma and Louisiana enacted sweeping criminal justice reform legislation in 2016 and 2017, respectively.

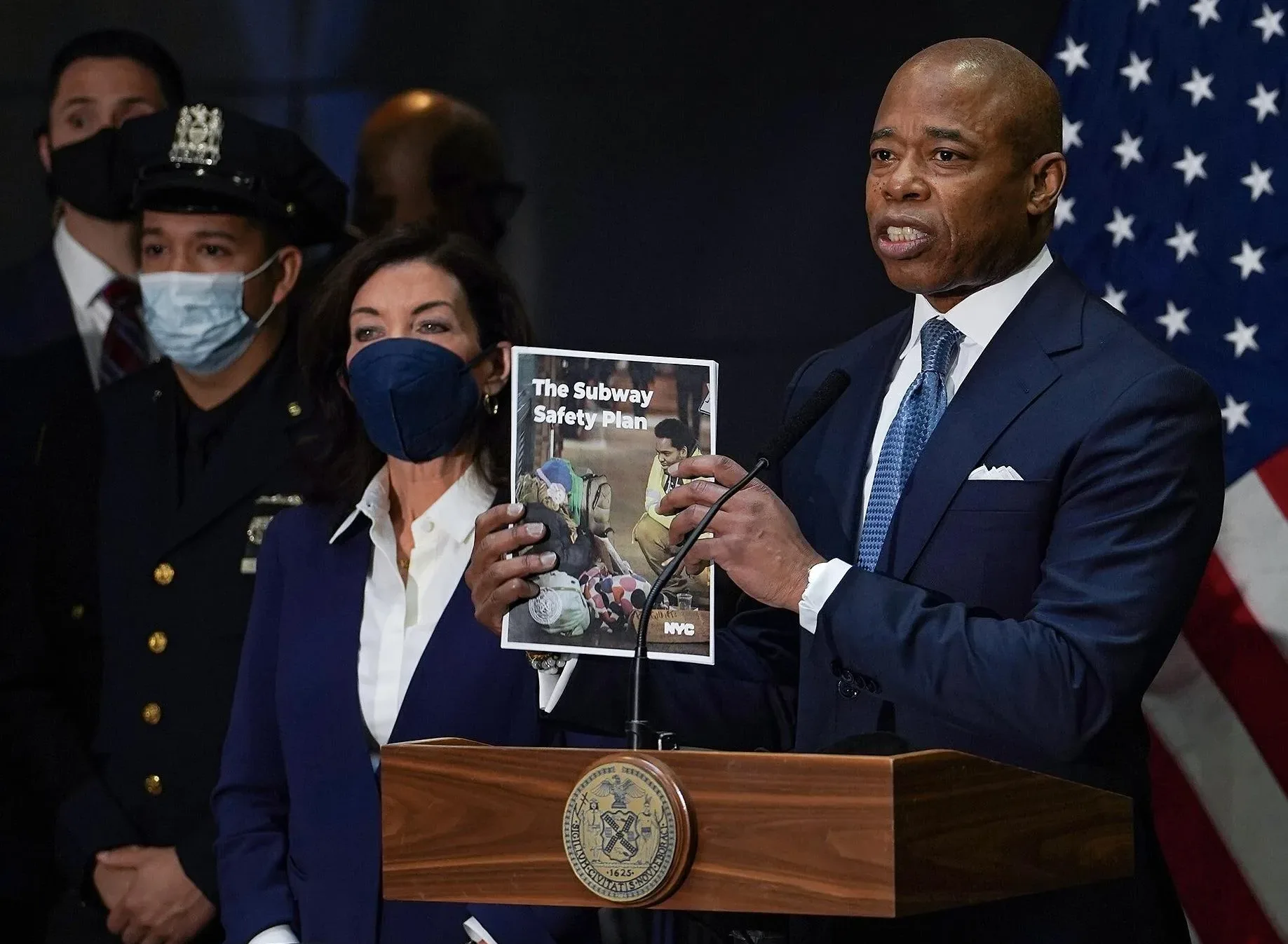

Since 2020, however, punitive approaches to public safety have come back in style. Progressive prosecutors have left office in jurisdictions like San Francisco, Orlando, and St. Louis, ousted by voters and hostile state officials. Numerous states have enacted harsh new penalties for drug crimes and retail theft. Landmark victories for the reform movement, such as New York’s 2019 bail reform legislation, have been rolled back by the same legislators who initially passed them.

On the surface, this shift towards “tough on crime” policies and rhetoric may appear to be a natural response to voters’ growing concerns about public safety. But this simplistic narrative misses a more nuanced understanding of Americans’ complex and often contradictory attitudes toward the criminal-legal system. Not only are perceptions of crime out of whack with reality, but public opinion polls show that most voters still support efforts to reduce incarceration, increase police accountability, and invest in alternative approaches to public safety.

According to Insha Rahman, vice president of the reform-minded lobbying group Vera Action, a blinkered focus on whether or not the U.S. is “tough enough” on crime ignores the fact that lawmakers can address public safety concerns without using punitive tactics or rolling back reforms.

“What kind of crime are they concerned about? And what kinds of solutions do they think actually work to address the concerns that they have?” Rahman said. “When you start to ask those series of questions, one thing that becomes really apparent is the political conventional wisdom that concern about crime equals or assumes support for tough on crime in the traditional way that we think of it, that’s actually not true.”

Has the American Criminal-Legal System Gone “Soft”?

In some ways, the U.S. criminal-legal system has become less punitive over the past two decades. Policy changes like the legalization or decriminalization of marijuana across more than half the country helped decrease drug-related arrests from more than one million in 2012 to just over 200,000 in 2022, according to FBI data. Between 2001 and 2016, at least 30 states increased the dollar value to qualify for felony theft, effectively reducing the penalty for minor larceny incidents. At least 14 states have enacted policies to reduce or eliminate cash bail since 2009, making it easier for people accused of crimes to remain out of jail before trial.

Incarceration rates peaked nationally in 2008, when more than 2.3 million Americans were in prison or jail. In 2021, incarceration rates in the U.S. reached their lowest level since 1995, when prison and jail populations dropped to 2.1 million, due mainly to the effects of the pandemic. But the number of people behind bars is still orders of magnitude larger than it was before 1980, when prison and jail populations rarely exceeded half a million.

Critics of these reforms have blamed them for fueling increases in crime, accusing reformers of prioritizing the rights of people accused of crimes over those of crime victims. The problem with that narrative is that there’s little evidence that crime has worsened nationwide—or that jurisdictions that enacted reforms experience more crime than those with stricter policies.

“The evidence is actually that reform has been consistent with–and certainly hasn’t undermined–safety and in some cases appears to advance safety,” Rahman told The Appeal.

“In places like Massachusetts and Philadelphia where district attorneys have declined to prosecute low-level offenses, the research has actually shown that it enhances public safety because people, if they avoid contact with the system, are less likely in the future to be arrested.”

On a national level, the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report (UCR), which is composed of data submitted by law enforcement agencies, shows that crime rates for most offenses rose slightly during the first two years of the pandemic. However, those numbers have fallen back below pre-pandemic levels in recent months. The UCR, of course, can’t measure crimes that never get reported to police. But the most recent National Crime Victimization Survey, which tracks data from victims of crimes regardless of whether or not they reported the incidents to police, also suggests crime remains at or near record lows. There are some exceptions to this overall trend, most notably when it comes to homicides, which increased by an unprecedented 30 percent in 2020. But that spike also appears to have been temporary, and murder rates have fallen sharply since peaking in 2021. While even one murder is one too many, it doesn’t point to a criminal-legal system unraveling at the seams.

On a local level, some places that have enacted significant reforms have seen sharp increases in crime. Washington, D.C., for example, saw murders hit a 26-year high and carjackings double in 2023 after enacting a slate of wide-ranging criminal justice reforms the previous year. (Congress later overturned some of those changes.) However, some cities that have resisted reforms have also experienced rising crime rates. For example, homicides hit record levels in Memphis last year—despite its state and local governments doing virtually nothing to roll back the city’s systems of punishment.

Why Do Americans Think Crime Is Out of Control?

Despite these facts, more Americans say they are concerned about crime today than at any other point in the 21st century. Historically, perceptions of crime have rarely matched reality. However, the gap between public opinion and official crime statistics has never been wider.

“Perception is shaped not by numbers and data, but by two things: what people feel and see when they go outside, and what people hear and read on the news,” Rahman said.

The biggest culprit for Americans’ inflated fears about crime and safety is the local and national media. In 2021, an analysis by FWD.us found that, between 2019 and 2020, support for bail reforms in New York plummeted from 55 percent to 37 percent after an onslaught of negative media coverage. Likewise, a recent report by the Center for Just Journalism found that news outlets cover violent and property crimes far more often than other social problems that cause similar levels of harm. For instance, 10 major newspapers published nearly 5,000 articles on retail theft between 2018 and 2022, compared to just over 100 stories on wage theft, even though wage theft costs working people an estimated $50 billion a year. Adding to the constant drumbeat of crime coverage, Republican candidates in the 2022 midterms ran thousands of ads blaming Democrats for supposedly skyrocketing crime rates.

Rahman notes that some efforts to respond to voters’ concerns about crime have backfired. When Democratic political leaders in New York reacted to the backlash against bail reform, many endorsed efforts to roll back the reforms instead of defending the legislation they had just passed. Less than three weeks after the legislation took effect in January 2020, Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins held meetings with bail reform opponents to discuss revisions to the law. By February, she had already announced a plan to repeal some of the reforms’ key provisions. By April, then-Governor Andrew Cuomo was signing the rollbacks into law.

In doing so, they added to the perception that bail reform was bad for public safety and undermined voters’ confidence in their ability to pass sensible policies. After all, if the same people who enacted bail reform aren’t willing to defend it, why should voters trust them to be stewards of public safety?

Rahman also points out that when people talk about “crime,” they’re often really talking about signs of public disorder.

“In many places across the country, especially in cities like New York and San Francisco, LA, Portland, and Seattle, people walk outside, and there’s a feeling of disorder,” Rahman said. “There’s more trash in the streets, they see more people without homes, they see more open-air drug use. It lends itself to a sense of disorder, and disorder gets conflated with crimes.”

The number of Americans dying from drug overdoses has quintupled over the past 20 years. Fatalities from auto accidents hit a 16-year high in 2021. Last January, homelessness in the United States reached its highest level since the federal government started keeping track in 2007. Mass shootings, while still just a fraction of overall murders, remain a regular occurrence while politicians block efforts to reduce access to assault rifles. No wonder many people feel less safe than they did a few years ago.

The bottom line is that concern about crime is often a proxy for broader fears about social disorder. Public safety is about more than just the number of robberies and assaults that occur in a given year; it is also about whether people feel safe when they leave their homes. And those vibes have been way off during the past four years.

What Do Americans Want Policymakers to Do About Public Safety?

Regardless of why concerns about crime have grown, elected officials across the political spectrum have reacted to this news by re-discovering their love for police and prisons. In his 2022 State of the Union address, President Biden declared, “We should all agree the answer is not to defund the police. It’s to fund the police. Fund them. Fund them. Fund them with the resources and training — resources and training they need to protect our communities.”

Even policymakers inclined towards reform have felt compelled to retreat in the face of political backlash.

“People feel like backlash is like the weather, that there’s nothing you can do except wait for it to pass,” Rahman said.

The reality is that voters remain receptive to policies aimed at reducing the harms of police violence, criminalization, and mass incarceration as long as policymakers also offer solutions to improve public safety.

The same Gallup poll in which the majority of adults surveyed said the criminal-legal system is “not tough enough” also found that most Americans don’t think police and prisons are the answer. In response to a question that asked whether “more money and effort should go to addressing social and economic problems such as drug addiction, homelessness, and mental health” or, instead, “more money and effort should go to strengthening law enforcement,” 64 percent of respondents picked the first option.

Bolstering these findings, a poll commissioned by Vera Action in September found that the majority of voters prefer increased funding to address the root causes of crime and disorder, such as better schools, affordable housing, mental health care, drug addiction treatment, and reduced access to firearms.

The poll also found that voters were more likely to support candidates who embraced a comprehensive approach to public safety. In contrast, when both candidates used “tough on crime” messaging, voters were more likely to pick the Republican.

This dynamic recently played out in Illinois, where Republicans tried to claim that people released due to the Pretrial Fairness Act—a state law that eliminated cash bail—had gone on to commit rampant crimes. Instead of adopting their tough-on-crime rhetoric or dismissing concerns about crime altogether, Illinois Democrats successfully defended their reforms and proposed alternative solutions for improving public safety.

“They actually owned the issue and reminded voters about why we need accountability and justice and why we need bail reform,” Rahman said. “They explained how it puts safety and not wealth as a priority for who is released after an arrest. And then they also said that you have really valid concerns about increased shootings and carjackings and other kinds of crimes. If you blame the wrong causes, you’ll miss the right solution. Rolling back bail reform isn’t going to address gun violence or carjackings. So let’s talk about solutions that do work.”

Rahman said the takeaway is that lawmakers can simultaneously address crime concerns and reduce legal system injustices. Voters are eager for solutions to both problems. Politicians just have to offer them.

“Voters are signaling that they’re concerned about crime,” she said. “There are some voters that fully believe in the ‘tough-on-crime’ approach. But that’s not the majority of voters. The problem is that elected officials and candidates are only listening to the minority that want a tough-on-crime approach, and that’s the only thing they’re saying about crime and safety.”

She added: “We have a narrative opportunity to talk about some of these other things like good programs, more mental health treatment, to talk about them as immediate crimefighting interventions. And if you label it as that, it helps to get over the skepticism that communities and voters have.”