Michigan Counties Ban Jail Visits to Profit From Videochat Fees, Lawsuits Say

“That video visitation is going to work,” one Genesee County official reportedly said in 2012. “A lot of people are going to swipe that Mastercard and visit their grandkids.”

Two lawsuits filed in state court today allege counties in Michigan are depriving children of their constitutional right to visit and hug their incarcerated parents—and that the municipalities are doing so to make money.

The lawsuits say St. Clair County and Genesee County conspired with the prison telecommunications firms Securus and Global Tel*Link (GTL), respectively, by giving the companies lucrative contracts that exploit incarcerated people and their loved ones. The companies then allegedly split the profits with the counties.

“That video visitation is going to work,” one Genesee County official reportedly said in 2012. “A lot of people are going to swipe that Mastercard and visit their grandkids.”

The civil rights attorneys, who are suing each county individually, seek immediate preliminary injunctions against the family-visit bans. The suit says the bans have had catastrophic consequences for detainees, many of whom are presumed innocent and only detained because they can’t afford bail.

One child, identified in documents as M.M., told the court in a statement that she had not been able to hug her father since his arrest in October. The suit says he’s been at the St. Clair County Jail for about five months.

“My dad is a very nice person and he loves me very much,” M.M. told the court. “I want to help other kids like me be able to see their parent.”

The counties and GTL did not immediately answer messages from The Appeal. We will update this story with their responses. Securus declined to comment.

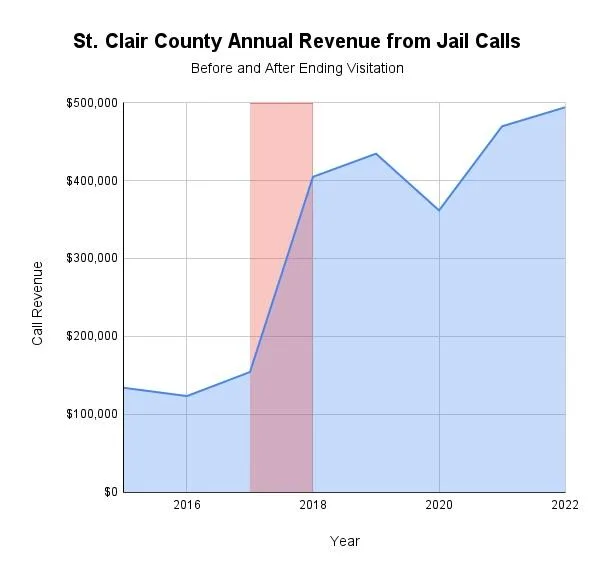

The lawsuit filed today against St. Clair County alleges that county officials banned in-person visitation in 2017 so they could profit from detainees’ expensive video calls.

The nonprofits Civil Rights Corps and Public Justice, as well as the law firm Pitt McGehee Palmer Bonnani & Rivers, sued St. Clair County, its sheriff, Securus Technologies, and investment firm Platinum Equity, LLC, which bought Securus in 2017. Billionaire and Detroit Pistons owner Tom Gores, who is also named as a defendant, is the chair and CEO of Platinum Equity.

“Defendants cannot, consistent with the Michigan Constitution, conspire to prohibit in-person family contact as part of a scheme to make money,” the complaint says. “Defendants decided to prohibit in-person visitation in order to make them money, not to address any public safety or law enforcement interest.”

The suit says in-person visitation is banned at the 16 Michigan jails that contract with Securus.

The complaint adds that, under the contract terms, Securus pays the county a $190,000 up-front payment. Once the county’s revenue share exceeds that annual lump sum, the suit says the company gives the local government half the cost of every $12.99, 20-minute video call and almost 80 percent of each $0.21 per-minute phone call.

The plaintiffs allege the deal gives the county a financial incentive to lock up as many potential Securus customers as possible. The complaint says that the contract with Securus stipulates that if the jail population drops by more than 5 percent, the company can reduce the county’s telephone commission and annual payment.

Detainees are allegedly offered one free video call per week, but the visitor must travel to the jail to use it. The suit says the calls are plagued with technical difficulties that often make the visit impossible.

The county has allegedly seen rising profits since it eliminated in-person visitation. The suit says that, in the three years before the county banned visits, call revenue made up 4 percent of total jail revenue. But from 2017 to 2022—the most recent years for which data is available—the suit says videochat fees jumped to 14 percent of the jail’s finances. In 2021, video call money allegedly made up nearly one-fifth of the budget.

“Well that is a nice increase in revenues!” a jail administrator for St. Clair County wrote to her colleagues in 2018, according to emails shared in the lawsuit.

“Heck yes it is!” St. Clair County’s accounting manager responded. “Keeps getting bigger every month too.” She ended the message with a smiley-face emoji.

The separate lawsuit filed against Genesee County today names the sheriff, GTL, and company CEO Deb Alderson as defendants. Like the suit against Securus, the attorneys allege that county officials separated parents and children to make money.

The lawsuit states that, under the county’s contract with GTL, the company pays more than $240,000 a year from the profits it makes from phone calls and video visits. The contract also gives GTL the right to end its video call service “if the Sheriff does not produce sufficient cash revenue from the video calls for the Defendants to split between themselves.”

The suit says Genesee County officials banned in-person visitation in 2014, allegedly as part of the same type of kickback scheme used in St. Clair County. According to the suit, the county then switched to GTL in 2018 when the company offered them a potentially more profitable deal.

The plaintiffs’ attorneys allege that the county’s family visitation ban forces low-income families to make impossible decisions: maintain some form of contact with their loved one by paying $10 for a 25-minute video visit or use that money to pay for other necessities such as food, rent, or gas.

The suit says parents and their young children have borne the brunt of the company and county’s greed.

A 15-year-old child, identified as A.H. in court documents, says she was separated from her father for more than a year while he was incarcerated in Genesee County Jail.

She said she used to go to the jail with her sister, mother, and aunt, who would all stand outside the building to wave to her father. They couldn’t see his face, but he would “do a special wave to signal that it was him.”

“We could never call my dad; he could only call us,” A.H. wrote to the court. “If I argued with my mom or sister, I’d go into my room and cry. I wish that I could have hugged him or talked to him then.”

This is a breaking story. This post will be updated.