Why Public Defenders Matter More Than Ever in a Time of Reform

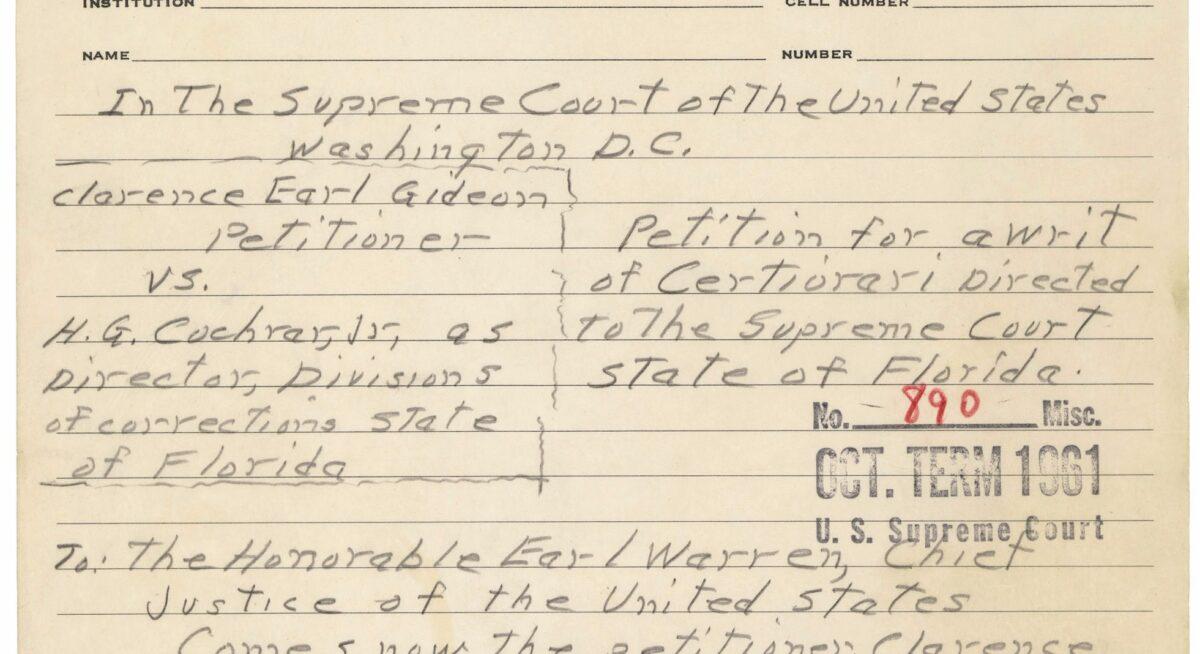

In 1963, the Supreme Court handed down Gideon v. Wainwright, which held that the government had to provide a lawyer to any poor defendant facing prison time. While often trumpeted as one of the Court’s greatest modern decisions, it has also been embroiled in controversy from the beginning. Like all Supreme Court opinions that impose new […]

In 1963, the Supreme Court handed down Gideon v. Wainwright, which held that the government had to provide a lawyer to any poor defendant facing prison time. While often trumpeted as one of the Court’s greatest modern decisions, it has also been embroiled in controversy from the beginning. Like all Supreme Court opinions that impose new obligations on state governments, Gideon was an unfunded mandate — and, given the political unpopularity of criminal defendants, the states have aggressively gone out of their way to make sure that this constitutional obligation stays unfunded.

Critics of the American criminal justice system have often pointed to Gideon’s failure as a major cause of mass incarceration, and of mass punishment more broadly. And they have proposed myriad ways, including increasing defender funding, to try to fix or repair or improve how we provide legal services to the poor. I count myself among those who have done so, having argued that funding indigent defense nationwide is one of the few steps the federal government could take that would really make a difference (although this is obviously not something that this administration would do).

To many, realizing Gideon’s vision of effective counsel for all is seen as one of the, if not the, most important steps toward real criminal justice reform that we can take. Indeed, one of the more high-profile reform groups is Gideon’s Promise, a nonprofit that partners with public defender offices around the country to implement best practices in public defense and has been the subject of a documentary aired on HBO.

There is no doubt that the work public defenders do is vitally important, and there is no doubt that they are underfunded — both in absolute terms, and compared to far better-funded prosecutor offices. Improved funding for indigent defense should be an important part of criminal justice reform.

But what if an emphasis on Gideon raises serious problems at a more fundamental level? What if pouring money into indigent defense really wouldn’t make the sort of difference for which many hope? What if Gideondistracts us from what really matters — or, worse, what if focusing on Gideonmakes more impactful reforms harder?

Georgetown University law professor Paul Butler made just this argument a few years ago in a provocatively titled Yale Law Journal piece, “Poor People Lose: Gideon and the Critique of Rights” (a not-at-all-stuffy-law-review essay everyone should read). Butler raised several powerful points, but here I want to focus on just one of them: that mass incarceration and mass punishment are not really the product of procedural breakdowns in individual cases — which is the implicit assumption of Gideon-focused reforms — but rather the result of systemic and systematic decisions about who to arrest, to charge, to send to prison.

I think Butler’s critique is spot-on. And, even just a few years ago, it was a powerful argument against directing too much attention and resources toward Gideon. But the politics of criminal justice have changed sharply over the past few years, and so too has, perhaps, the role that Gideon can play in bringing about real change.

For Butler and others, the jumping-off point of Gideon’s limitation is something that often gets overlooked in all the discussions of wrongful convictions, Brady violations, false confessions, bad forensics, and conviction integrity units: most — perhaps almost all — who are arrested, charged, convicted, and sentenced are guilty of a crime. Our criminal laws are sprawling, open-ended codes that punish people for wide swaths of behavior. More often than not, defense work is about triage, about minimizing the harms that come from an almost-guaranteed — and legally sound — conviction.

The core problem with Gideon-focused reform is that mass incarceration is driven by decisions made by police and prosecutors about who to arrest and who to charge, not procedural issues about how the arrest is made or how the trial or plea bargain is conducted. The criminal justice system is a blunt tool, and not everyone who violates the terms of a criminal statute should be arrested, charged, convicted, sentenced.

In fact, Butler suggests that focusing on Gideon might make reforms harder, by effectively white-washing the substantive injustices of our criminal justice system, such as disparities in which groups (such as low-income Black men) face higher risks of arrests, charges, and convictions, for the same conduct.

So while evidence suggests that competent indigent defense makes a difference — what few studies we have suggest that those with better lawyers are less likely to be convicted or serve less prison time — the traditional role of public defenders is individualistic and reactive: They handle the specific cases that the police arrest and the prosecutors charge.

In other words, while improving the often-frightening procedural failings of the criminal process is important work, real reform lies far more in changing the systemic choices made by police and prosecutors. The decisions about where to deploy police, what sort of arrest policies to have, what sort of cases prosecutors get charged vs. dismissed — these are the decisions that really drive mass punishment.

This is why, Butler suggests, focusing on Gideon risks making reform harder. If everyone has a decent lawyer, then we might be less troubled by why some people are more likely to need that lawyer in the first place.

Yet, suddenly, perhaps public defenders are in a position to make these changes. Perhaps today, Gideon can serve a new, substantive function.

Over the past few years, at least in more urban counties, voters have started to push prosecutors to adopt less harsh and more progressive policies. The changes they demand are systemic, not individualistic: to no longer ask for cash bail in entire categories of cases, to stop prosecuting entire types of offenses (such as marijuana and low-level theft), and so on. Prosecutors are facing political pressure to shift from tough-on-crime to something far more “smart-on-crime”-like, and they are increasingly making promises along those lines.

But promises are just words, and sometimes it seems like prosecutors running for election or re-election are quickly learning a set of reformist buzzwords they can trot out to voters — but then struggle to implement in practice. Many observers were deeply disappointed with former Brooklyn District Attorney Ken Thompson’s broken promises on declining to prosecute low-level marijuana cases. Thompson died of cancer in the fall of 2016 and court monitors report that under Brooklyn’s current DA, Eric Gonzalez, they still see marijuana possession cases whenever they’re in court. Manhattan DA Cy Vance, meanwhile, continues to promise to stop charging people with jumping turnstiles, yet seems to keep doing so.

The potential disconnect between promise and practice has become sufficiently concerning that at least in New York City, a group of nonprofits, including a coalition of public defenders, recently created Court Watch NYC, which sends observers to courts across the city to make sure that DAs are living up to their reformist promises.

The role of public defenders is thus clear: They’re in the best position to ensure that progressive-sounding prosecutors fulfill their campaign promises. Unlike court watchers, they are present at every step of the process — not just public hearings, some of which might be held in the middle of the night — but the behind-closed-doors plea bargaining processes that resolve about 95 percent of all cases. They see the charges that prosecutors threaten and then withdraw, the factors that seem to shape prosecutors’ decisions about when they drop charges and when they move forward, and so on.

Real reform requires real data, but prosecutor offices are notoriously stingy with their numbers. About 80 percent of all defendants nationwide qualify for indigent representation, which means that while defender offices do not handle every case, they handle most, and a data-rich annual report from a public defender’s office would inevitably provide a detailed picture of what the prosecutor’s office is up to as well.

As voters, or at least urban voters, increasingly demand a new form of criminal justice, there is increasingly a role for public defenders to ensure that substantive, systemic change happens. All of this, however, takes time — and money. If public defender offices cannot fulfill their basic ethical — and constitutional — obligations to represent their clients, they certainly can’t start generating data or court-watching reports.

In fact, the role of public defender offices could expand even more. When criticized for being excessively harsh, prosecutors often like to say that they are only doing what the legislature has instructed them to do. It’s a doubly disingenuous claim, not just because “prosecutorial discretion” means that prosecutors are not required to be as harsh as the legislature permit, only that they can be — but because many of those tough laws come about from aggressive lobbying by statewide district attorney associations.

As criminal justice reform becomes more politically tenable, however, there is room for public defender offices to take on a lobbying role as well. They are well-positioned to tell legislators the stories about the costs of excessive and counterproductive harshness, to help put a human face on the costs of punitiveness — and, as lawyers, to suggest how to change specific statutes and rules to minimize those harms. But this too requires funding.

It’s worth pointing out that the proposals here would only work in counties or states with centralized public defender offices, as opposed to those that contract indigent defense to otherwise private lawyers. But that could just mean that fulfilling Gideon’s more-meaningful promise also means pushing jurisdictions that don’t have public defender offices to adopt them.

Historically, public defenders have played primarily procedural roles — profoundly important, constitutional roles to be sure, and ones that should be far better funded than they are, even if you ignore all the arguments I’ve made here. But mass incarceration and mass punishment are not really the products of procedural failings at the trial stage. They are far more the result of discretionary choices by police and prosecutors, as well as judges and legislators. Yet in this reformist moment, as voters demand smarter policies from still-opaque prosecutor offices, and as legislators seem more open to less-punitive approaches to social problems, public defenders are well positioned to play a critical role—which makes the role of Gideon all the more important.