New Jersey ‘Shaken Baby Syndrome’ Ruling Puts ‘Junk Science’ Diagnosis Under Fire

In a decision last month that could impact other cases, an appellate court ruled that “the very basis of the theory has never been proven.”

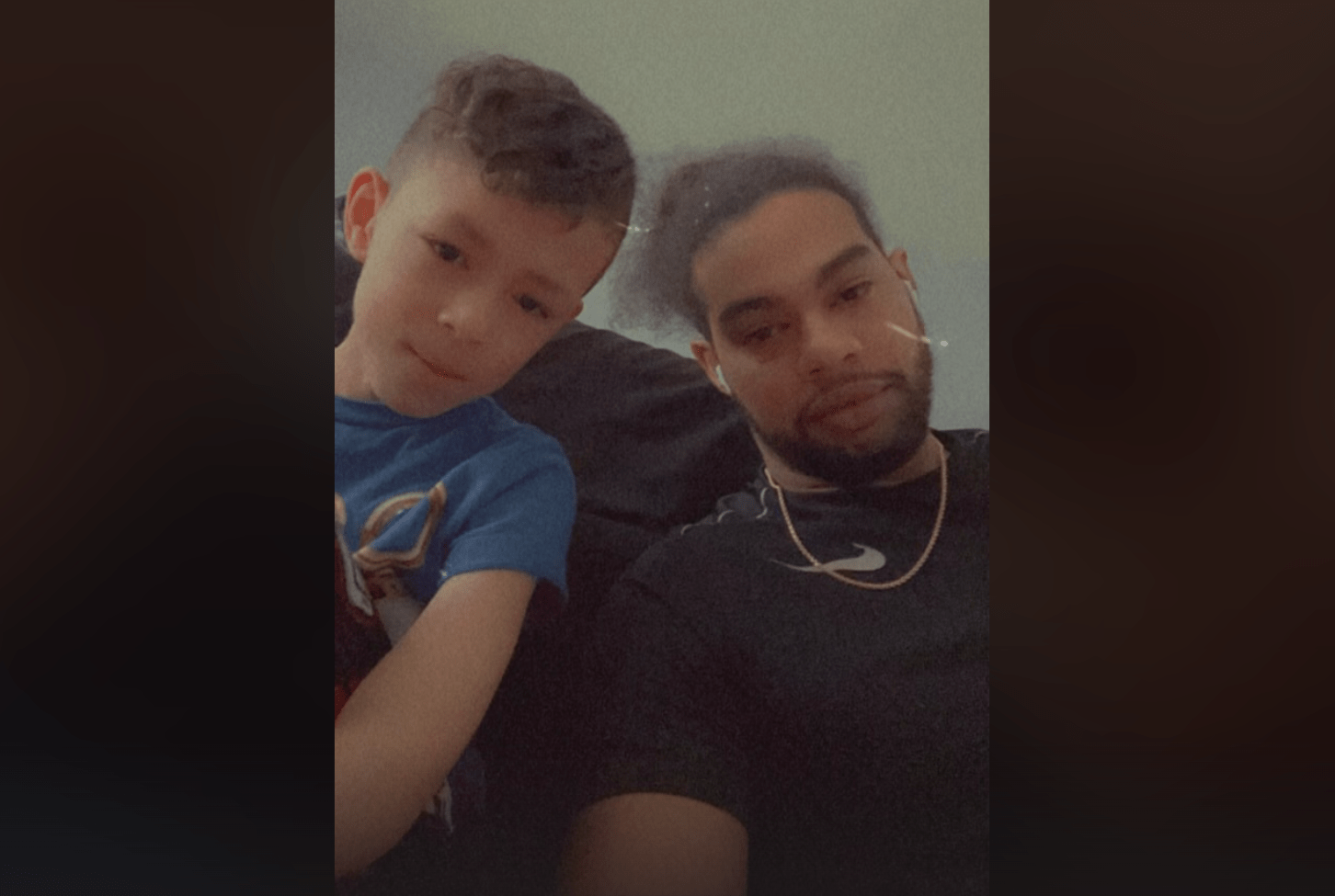

Darryl Nieves’s wrongful prosecution began as many Shaken Baby Syndrome cases do—with a call for help.

On February 10, 2017, Nieves’s 11-month-old son, D.J., appeared to be having a seizure, Nieves told The Appeal. He called 911. The paramedics arrived, administered oxygen, and D.J. regained consciousness. They took him to St. Peter’s University Hospital in New Brunswick, New Jersey, the same hospital where D.J. had been born prematurely, at just 25 weeks gestation, according to a brief filed by Nieves’s attorneys with the Office of the Public Defender. (The Appeal is using the child’s nickname to protect his privacy.)

Despite D.J.’s well-documented medical conditions—he’d spent the first seven months of his life hospitalized and had already undergone two cardiac surgeries—a child abuse pediatrician at the hospital diagnosed him with abusive head trauma, or AHT, “as occurs with a shaking event with or without impact.” This diagnosis is often known as Shaken Baby Syndrome.

Nieves was arrested and charged with aggravated assault and child endangerment. He was released after about four days in jail but was not allowed to have any contact with his son, he said. It would be more than four years until he could see D.J. again.

“I was thinking the government fails everyone, especially Black African Americans, so I felt it was going to fail me,” Nieves told The Appeal.

Prosecutors offered him probation if he pleaded guilty, according to Danica Rue, a member of Nieves’s legal team at the public defender’s office. Nieves turned it down.

The then-26-year-old father appeared to be on the same catastrophic path that has sent many parents and other caregivers to prison based solely on a doctor’s “shaken baby” diagnosis.

“Detectives were saying the doctor has proof; the doctors are never wrong,” Nieves said. “That’s what they were saying to me. Basically trying to scare me into admitting something I didn’t do.”

But then something happened that changed the course of Nieves’s case and future Shaken Baby Syndrome prosecutions in New Jersey.

On January 7, 2022, after years of delays, a trial judge sided with Nieves’s defense and ruled that prosecutors could not introduce testimony on Shaken Baby Syndrome in the case. The judge declared the controversial theory “akin to junk science” and, a few weeks later, dismissed the indictment against Nieves.

The Middlesex County Prosecutor’s Office appealed to the Superior Court of New Jersey. In a decision last month, the superior court affirmed the trial judge’s ruling.

“The very basis of the theory has never been proven,” Judge Greta Gooden Brown wrote in the court’s opinion. “The State has not demonstrated general acceptance of the SBS/AHT hypothesis to justify its admission in a criminal trial.”

The prosecutor’s office says it intends to appeal the ruling to the Supreme Court of New Jersey.

The previous appellate court ruling is still significant, explained Rue. State judges have now repeatedly found that the SBS/AHT theory is “not scientifically valid.” That casts further doubt on “shaken baby” diagnoses in cases with similar fact patterns, where a person is accused of causing a child’s injuries by shaking alone. The precedent-setting nature of these findings may depend on how the state Supreme Court rules—if they decide to hear the case at all. But for the time being, the legitimacy of this evidence hangs in the balance.

Proponents of the controversial “shaken baby” theory say that such victims suffer from a specific triad of symptoms that would only otherwise appear if a child had fallen from a multi-story building or been in a car accident. In many past cases, a physician’s shaking diagnosis has set police and prosecutors off to zero in on the last person with the child as the only viable suspect. Frequently, this has been the caregiver who called 911 for help.

But there are other explanations for a child’s collapse. Several studies and exonerations have demonstrated that strokes, trauma from childbirth, short-distance falls, seizures, and illness can cause a child to suddenly fall unconscious, even though they had appeared lucid immediately beforehand.

Last month, Michael Griffin became the 32nd person in the U.S. exonerated in a “shaken baby” case since 1989, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. When he brought his daughter to the hospital in 2009, he told staff that his seven-month-old daughter had fallen from her motorized swing. Griffin was arrested weeks later, prosecuted for his daughter’s murder, and sentenced to life in prison. Griffin served more than 10 years of his sentence before he was released.

“Shaken baby” arrests, prosecutions, and convictions have continued despite the mounting evidence that the theory is deeply flawed. In Texas, Robert Roberson, an autistic father, is on death row after his conviction for shaking his two-year-old daughter to death, a crime he says he didn’t commit and that likely never occurred. As in Nieves’s case, Roberson’s daughter had serious medical issues since birth, according to news reports. On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear his case, clearing the way for Texas to set an execution date. In 2016, Roberson’s attorney secured a stay just four days before his scheduled execution.

In New Jersey, Michelle Heale is serving a 15-year sentence for a crime that experts say likely never occurred. She was convicted of aggravated manslaughter in 2015 after prosecutors alleged she shook to death a 14-month-old in her care. The Appeal published an investigation into Heale’s case in 2020, which prompted University of South Carolina School of Law professor Colin Miller to begin looking into her conviction.

Last year, Miller submitted an application on Heale’s behalf to the New Jersey Attorney General’s Conviction Review Unit. The unit has not yet reached a decision on her application, according to a spokesperson for the Attorney General’s office. In an email to The Appeal, the spokesperson said that Heale’s case appears to be the only shaken baby case before the CRU.

The New Jersey Superior Court’s assessment of shaking cases further confirms what research and exonerations have already revealed about the diagnosis, Miller told The Appeal.

“Shaken Baby Syndrome has always stood on a foundation that was a house of cards,” he said.

It’s not clear how many people in New Jersey may be affected by the court’s decision in Nieves, said Jennifer Sellitti, director of training at the state public defender’s office. She said she’s working with her colleagues to identify former and current clients who may be impacted and to educate New Jersey defense attorneys about the decision.

“If any lawyer has a case that fits the factual scenario we’re talking about here, they would want to argue that this case is precedent, and it should prevent this evidence from coming into those trials as well,” Sellitti said. If the state Supreme Court takes up the Nieves case, defense attorneys may argue that the trial court should not rule on the admissibility of “shaken baby” evidence until that decision comes down, she added.

The impact of the Nieves ruling isn’t necessarily limited to New Jersey. Sellitti said defense attorneys from other states have contacted her office hoping to use the Nieves decision to persuade their own courts to issue similar rulings.

While the court’s decision in Nieves’s case may help curtail future wrongful prosecutions in New Jersey and throughout the country, that won’t replace the years Nieves has lost with his son. No one associated with his prosecution has offered an apology, according to Rue, his lawyer.

Last year, Nieves finally reunited with D.J. after more than four years apart. Before their forced separation, Nieves said he spent almost every day with his son.

“He didn’t really remember me because he was a baby at the time,” said Nieves. “It was very difficult at first.”

Nieves now lives with his partner, D.J., and his stepson. While his case was pending, Nieves wasn’t allowed to have so much as a phone call with D.J. The state’s prosecution robbed him of “the most valuable thing,” he said—time with his family.

“At this point, there’s nothing that can fix that,” Nieves said.