How Dubious Science Helped Put A New Jersey Woman In Prison For Killing A Baby In Her Care

The state said Michelle Heale shook the baby to death, but some experts say her conviction was based on debunked science.

On Aug. 28, 2012, Michelle Heale was home in Toms River, New Jersey, with her 3-year-old twins, and 14-month-old Mason Hess, whom she had been babysitting for about a year.

Mason’s mother, Kellie Hess, had volunteered to keep him home. The day before, he threw up at Heale’s, and was diagnosed with ear and upper respiratory infections. His pediatrician prescribed antibiotics.

“R u sure i don’t want to get any of you sick,” Kellie texted Heale on Aug. 27. “Won’t be the first time, won’t be the last time. Everyone will be fine,” Heale replied.

On the morning of Aug. 28, Kellie dropped off Mason. He ate his breakfast and played with the twins, according to texts between Kellie and Michelle. According to Heale’s account, at about 2 p.m., she fed him applesauce. He coughed, and she patted him on the back. She went to feed him more, but suddenly it appeared he could not breathe. She placed him on her shoulder and patted his back until applesauce came out on her shirt. She put him back down; his body went limp. Carrying Mason, she ran down the hallway for her phone to call 911. She swept his mouth to make sure it was clear.

“He has no movement in any parts of his body,” she told the 911 operator, who urged Heale to stay calm. “His whole body is lifeless.”

A police officer arrived, then an ambulance. Heale tried to call Mason’s father, Adam Hess, but his number was not in her new phone. She went to the local hospital with the officer.

Dispatch called Adam, who then picked up Kellie. At the hospital, the emergency room doctor looked at Mason’s chest X-ray and diagnosed him with pneumonia. The doctor also found elevated white blood cell counts which could indicate a bacterial infection.

That afternoon, Mason’s parents chose to send him to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). Adam went with Mason by helicopter. Mike, Michelle’s husband, drove Kellie and Michelle. The couples had met when Mike and Adam worked together as detectives in the Ocean County prosecutor’s office. They had been friends for about five years.

Mason never regained consciousness. On Aug. 31, doctors Samantha Schilling and Philip Scribano, members of CHOP’s Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect Team, told police that Mason had suffered a “severe brain injury” and bleeding in his eyes, according to a police report. The officer wrote, “The doctors concluded that the only diagnosis was Abusive Head Trauma, and it’s ‘indisputable for a violent event.’” Mason, the doctors said, must have been shaken. Kellie and Adam told police that Heale would never hurt their son.

Mason was pronounced dead on Sept. 1. On Nov. 27, Heale was arrested for first-degree murder.

The state’s case was built on testimony from the hospital’s doctors, as well as two of the most well-known adherents to the diagnosis known as shaken baby syndrome (SBS). But critics say SBS has failed to survive scientific scrutiny, and Heale’s case, according to medical and legal experts, appears to have involved a rush to judgment based on questionable science.

“I think this case has all the hallmarks of a miscarriage of justice,” said Randy Papetti, a lawyer and author of “The Forensic Unreliability of the Shaken Baby Syndrome,” who reviewed Heale’s legal documents at The Appeal’s request. “The key people that testified against her are prominent figures whose views are greatly controversial and looking more and more unreliable by the day.”

Conflicting testimony

Heale’s trial began in March 2015. The state’s medical experts testified that Mason suffered retinal and brain hemorrhaging, or bleeding, and swelling of the brain. Heale caused these injuries, they alleged, when she shook Mason to death.

Alex Levin, chief of pediatric ophthalmology and ocular genetics at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, testified that a photograph of one of Mason’s eyes would be on the cover of the American Academy of Ophthalmology publication, “Focal Points.”

“I have never seen such a classic photograph that tells us and shows us what shaken baby syndrome eye findings are all about,” he told the court. “It’s just an iconic photograph.”

The only other possible cause, Levin said, was if “a television or something crushed his head, unless he was killed in a car accident, unless he fell 11 meters.” Another witness, Lucy Rorke-Adams, a neuropathologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia who examined Mason’s brain and spinal cord, told the jury that choking or “natural disease” did not cause Mason’s collapse. When asked by the prosecutor if there was any doubt that Mason had been shaken to death, Rorke-Adams replied, “No.”

Prosecutors discounted other evidence that potentially contradicted their theory, including that Mason was ill before he collapsed and that the emergency room doctor diagnosed him with pneumonia. There was also a bruise on his forehead, according to the autopsy report, and his parents testified it was caused by a fall in their home about a week earlier.

“Mason just walked into the sliders… think the bump now looks bigger. Leaving the screen on now!!!” Heale texted Kellie the day before his collapse, according to court documents. “Lol unreal,” Hess replied.

When asked by the prosecutor if there was any doubt that Mason had been shaken to death, Rorke-Adams replied, “No.”

Heale’s defense team called experts in pathology, biomechanics, and opthamology who testified that Mason was not shaken. It was unknown why he had suddenly collapsed, they said.

Pathologists Zhongxue Hua and John Plunkett testified that the injuries Rorke-Adams observed on Mason’s brain and spinal cord could have been caused by a condition known as “respirator brain.” Mason was on a respirator for several days, which can lead to brain pressure and damage to the spinal cord, they said. It was not possible, Plunkett added, for a person to shake Mason, who was 22 pounds, according to the paramedics report, violently enough to cause brain damage. Heale weighed 105 pounds at the time of her arrest, according to a police report.

“Shaking had nothing to do with Mason’s collapse or with his subsequent death,” Plunkett testified.

Retinal hemorrhages, Plunkett said, are present in a variety of cases. In a 2001 study Plunkett authored, he showed that symptoms thought to be associated with SBS could also be caused by short-distance, accidental falls—just one of several causes that experts in countless trials had excluded as impossible.

Heale sobbed frequently at her court appearances, according to news reports, and during her telephone interview with The Appeal from the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women. On the first day of her trial, she cried in her husband’s arms that she wanted to go home, the Asbury Park Press reported. Heale testified on her own behalf, maintaining her innocence as she had since she was first accused.

The case came down to which experts the jury believed. Ultimately, they sided with the state’s. Heale was convicted of aggravated manslaughter on April 17, 2015.

The Hesses testified that Heale, who had no history of violence, was a patient and loving caregiver for Mason and her own children. They came to support the state’s version of events, particularly once they learned the medical examiner had classified their son’s death as a homicide, according to Adam Hess’s statement to police. At Heale’s sentencing hearing, Kellie called her a “monster,” the Asbury Park Press reported. Adam said, according to the local paper, “We know that the devil has saved a special place in hell for you because only an evil being would hurt a child.” The Hesses declined to comment when contacted by The Appeal.

Heale told The Appeal that losing their trust was devastating. “When you tell the truth, you expect to be believed,” she said in a phone interview.

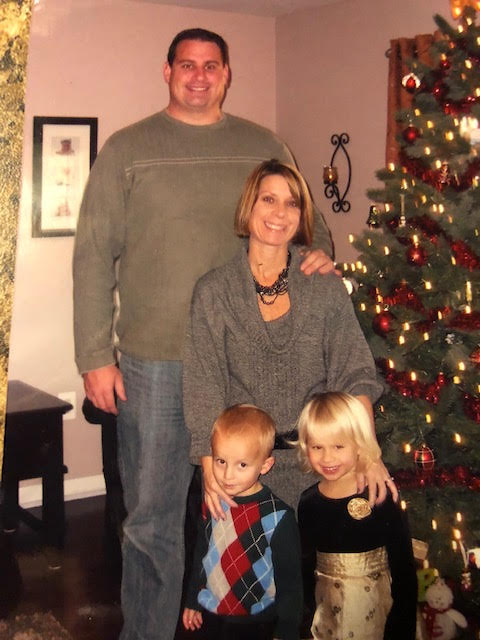

The judge sentenced her to 15 years in prison. At the time, her children were 6 years old.

“Mommy will come home,” Mike recalled telling the twins, reassuring them that she was safe and they could still see her. “It’s going to take a long time.”

Questioning an SBS diagnosis

Since the 1980s, there has been a steady climb in convictions for SBS, sometimes referred to as abusive head trauma, in U.S. courtrooms. In her book “Flawed Convictions: ‘Shaken Baby Syndrome’ and the Inertia of Injustice,” Deborah Tuerkheimer, a law professor at Northwestern University, wrote that before 1990, only 15 SBS cases were heard by appellate courts. Between 1990 and 2000, there were more than 200. And from 2001 to 2015, there were about 1,600 convictions in SBS cases, according to a study conducted by the Washington Post and the Medill Justice Project.

In the 1990s, medical experts routinely testified that the so-called triad—subdural hemorrhage, retinal hemorrhage, and brain swelling—could only be produced by violent shaking, a fall from a window, or a car accident, according to Tuerkheimer. The SBS diagnosis, she told The Appeal, is a “medical diagnosis of murder.”

“We continue to have prosecutions that are based on questionable scientific underpinnings,” she said. “What I care about is what is provable beyond a reasonable doubt in criminal court and there I think the science is not there.”

The hypotheses that undergird SBS were developed in the early 1970s. In 1971, A. Norman Guthkelch, a British pediatric neurosurgeon, speculated that babies could be shaken to death without any apparent external injuries, based on an examination of five babies. Those babies, he wrote, “had no external marks of injury on the head.” Then, in 1972 and 1974, John Caffey, a pediatric radiologist, published papers theorizing that “whiplash forces” could cause subdural bleeding and retinal hemorrhages. The condition he called “the whiplash shaken infant syndrome” would later be dubbed shaken baby syndrome. But Caffey cautioned at the time that “current evidence” was “manifestly incomplete and largely circumstantial.”

We continue to have prosecutions that are based on questionable scientific underpinnings.

Deborah Tuerkheimer law professor at Northwestern University

It has been on this problematic foundation that people like Heale have been convicted, said Keith Findley, co-founder of the Wisconsin Innocence Project and the Center for Integrity in Forensic Sciences. “It was never scientifically validated,” he told The Appeal.

These convictions follow a familiar pattern, according to Findley and other legal experts with whom The Appeal spoke—a pattern that is mirrored in Heale’s case: A baby collapses and is rushed to the hospital, but there are no external signs of abuse or trauma. At the hospital, the baby’s brain is scanned, Findley explained. If bleeding is observed, it triggers a concern for child abuse, he said. If retinal hemorrhages are also found, physicians may quickly conclude that the baby was shaken to death. Once this tunnel vision sets in, he said, medical professionals and investigators will “remember, understand, interpret all different data in a way that conforms to that original belief.”

“You look at the scan and you see subdural hematoma and think this looks like abuse,” he told The Appeal. “Pretty much everything thereafter is filtered through that lens, ‘We think it’s abuse.’”

Though prosecutors often portray the babies as having been in perfect health before the incident, it often emerges that they have been intermittently fussy, ill, or had trouble eating, according to Findley.

This pattern was observed in the case of Findley’s client Audrey Edmunds, who, like Heale, was accused of killing a baby in her care.

Almost two decades before Heale’s conviction, a Wisconsin judge sentenced Edmunds to 18 years in prison for shaking to death 7-month-old Natalie Beard. Beard’s parents testified that on the day of her death, before she arrived at Edmunds’s home, Beard was crying uncontrollably, according to a brief filed on Edmunds’s behalf by the Wisconsin Innocence Project. At the time, Beard was on antibiotics for an ear infection, according to the brief.

You look at the scan and you see subdural hematoma and think this looks like abuse. Pretty much everything thereafter is filtered through that lens.

Keith Findley co-founder of the Wisconsin Innocence Project and the Center for Integrity in Forensic Sciences

Edmunds testified that when she went into her bedroom to get Beard, she found the baby was unresponsive; Edmunds called 911. The state’s experts testified that Beard’s injuries could only have been caused by shaking, falling from a second- or third-floor window, or being in a car crash, and that her collapse immediately followed the violent event. In other words, the last person with the baby was responsible for her death.

“There was no evidence that the severe injuries Natalie sustained could have been the result of an accident, rather than intentional, forceful conduct, directed specifically at Natalie,” Judge Patience Roggensack wrote in her 1999 opinion for the Court of Appeals of Wisconsin, affirming Edmunds’s conviction.

In 2006, the Wisconsin Innocence Project presented evidence that showed in the intervening years between her conviction and appeals, research had established there could be other causes of Beard’s injuries. The pathologist who performed the autopsy on Beard—and had testified for the state at trial—now testified on Edmunds’s behalf that a baby could be conscious and then suddenly collapse, without an obvious precipitating event.

“The science that sent Audrey Edmunds to prison did not stand still,” her appellate attorneys wrote to the court. “Without the original medical unanimity, the State’s theory lost its foundation.”

The Court of Appeals of Wisconsin agreed and overturned her conviction. “At trial, and on Edmunds’s first post-conviction motion, there was no such fierce debate,” wrote Judge Charles Dykman. “Now, a jury would be faced with competing credible medical opinions in determining whether there is a reasonable doubt as to Edmunds’s guilt.” The state opted not to retry her and dropped the charges in July 2008. Edmunds is one of 17 people since 1989 who has been exonerated of an assault or murder involving SBS, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

‘Nothing to do with science’

Many features of Edmunds’s case are mirrored in Heale’s, including the testimony. Levin, the ophthalmologist who testified for the state in Heale’s case, also testified for the state at Edmunds’s evidentiary hearing. In both cases, he told the court that violent shaking produced the retinal hemorrhages the babies in those incidents incurred.

But a 2017 study published by the Belgian Neurological Society concluded that “there is no pathognomonic size, distribution, or location of RH [retinal hemorrhages] seen only in AHT [abusive head trauma].” Others question if shaking causes retinal hemorrhages at all.

Waney Squier, a pediatric neuropathologist in England who has researched SBS extensively, said there is reason to doubt that shaking produces any of the symptoms associated with the diagnosis. Squier pointed to an analysis published in 2016 by the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services. The report’s authors examined 1,065 studies on SBS to determine if shaking caused the so-called triad. The vast majority—1,035—were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, such as examining 10 or more cases. Of the 30 studies that met the study’s criteria, two were of “moderate quality” and none were of “high quality.”

“There is actually no science whatsoever that underpins the shaken baby hypothesis,” Squier told The Appeal. “This whole thing is based on what we believe, and nothing to do with science.”

Squier’s own position has changed over time, she said. In 2000, she provided the prosecution a report stating that Lorraine Harris, who was raising her family in England, had shaken to death her 4-month-old son. Harris was convicted and sent to prison. But on appeal, in 2005, Squier testified on her behalf, and Harris’s conviction was overturned. (Rorke-Adams, who testified for the state in Heale’s case, also testified for the prosecution in Harris’s case on appeal.)

I’d been responsible for her going to prison. I realized I was wrong.

Waney Squier pediatric neuropathologist, discussing her testimony against Lorraine Harris

“I’d been responsible for her going to prison,” said Squier. “I realized I was wrong.”

Squier went on to testify in other cases in which people were accused of shaking babies to death, telling the courts that SBS was not a valid diagnosis—statements that would jeopardize her career. In 2016, the General Medical Council ruled that her testimony in six SBS cases was dishonest and she was no longer permitted to practice medicine in the United Kingdom. On appeal, her medical license was reinstated, but she was banned from testifying as an expert for three years in U.K. courts.

“I challenged the mainstream,” said Squier. “I said it might be mainstream, but it’s not science.”

Plunkett, who testified for the defense in Heale’s trial, also faced repercussions for questioning popular thought. In 2001, Plunkett testified as an expert witness for the defense in the case of Lisa Stickney, a daycare worker who was accused of shaking a baby to death. After Stickney was acquitted, the Deschutes County, Oregon DA’s office filed charges against Plunkett for “false swearing,” which is akin to perjury. In 2005, he was acquitted. Plunkett died in 2018.

What happened to Squier and Plunkett is part of a “pattern of hostile attacks” against physicians who challenge the SBS hypothesis, Findley told The Appeal.

“It’s so antithetical to what should be the nature of scientific inquiry which should embrace criticism and open debate and open discussion,” said Findley. “We need to be sorting through these difficult medical and legal issues.”

Defenders of the diagnosis

Even as medical opinion has evolved, Levin and Rorke-Adams—two of the doctors who testified for the state in Heale’s case—have held fast to the diagnosis.

Levin has written extensively on SBS and serves on the advisory board for the National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome. At Heale’s trial, he told the jury the organization had recognized him for “outstanding leadership and support.”

“Dr. Levin, at least over the last 20 years, to me is the single most influential person in preserving the classic version of the shaken baby syndrome diagnosis,” said Papetti, author of “The Forensic Unreliability of the Shaken Baby Syndrome.”

Rorke-Adams was also recognized by the National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome. In 2014, she received an award for outstanding contributions in the field of shaken baby syndrome/abusive head trauma.

But prior to Heale’s trial, both doctors had testified against people who were later exonerated of shaking children in their care to death; the jury never heard this.

In 2005, Rorke-Adams testified in Harris’s appeal, and in 2007, Levin testified for the state in Edmund’s case. In 2014, the same year Rorke-Adams received her award, a federal judge in Illinois rebuked her testimony in the case of Jennifer Del Prete, a daycare worker accused of shaking a 3-month-old infant to death.

Prior to Heale’s trial, both doctors had testified against people who were later exonerated of shaking children in their care to death; the jury never heard this.

Called to testify by the state at Del Prete’s evidentiary hearing, Rorke-Adams told the court that the baby’s brain was “falling to pieces” and “hardly recognizable as brain.” The injuries were caused, she testified, by abusive head trauma by shaking.

However, the district court found a portion of her testimony “completely unbelievable and unreliable.” Rorke-Adams had, the judge wrote, “viewed the autopsy photo of the brain sections upside-down and had drawn erroneous and unwarranted conclusions from this.”

An expert for Del Prete testified at the evidentiary hearing that what Rorke-Adams had identified—mistakenly, she said—as a contusion was, in fact, an injury that occurred when the brain was removed during autopsy. The baby, she surmised, likely died of a blood clot in the brain.

“I don’t know if anything can make up for what I went through,” Del Prete said in 2017, about a year after her conviction was overturned. “But I never stopped fighting to make my way back to my kids and my family.”

Rorke-Adams did not respond to The Appeal’s requests for comment. In response to The Appeal’s questions, Levin wrote in an email to The Appeal, “I simply review the medical facts and relate those to the known science and try to provide the court with education in the matter.”

He went on to explain that, “there is no single finding in the eye” that is indicative of a particular condition. “But never should we use one single finding,” he wrote. “The diagnosis of abuse is based on careful consideration of all eye findings in the context of the systemic findings, laboratory results, pretinent [sic] negatives (what is absent), history and radiologic investigations.”

Looking ahead

In January 2018, the Superior Court of New Jersey affirmed Heale’s conviction. In June of that year, the Supreme Court of New Jersey refused to hear her case.

But about two months later, another New Jersey court questioned the validity of SBS. At a bench trial in Passaic County, Robert Jacoby was acquitted of aggravated assault. About four years earlier, Jacoby’s approximately 11-week-old son vomited and went limp while in his care. Jacoby took him to the hospital and was soon accused of causing the injuries by shaking.

“It is now well established and widely accepted in the scientific community that there are other alternate causes or conditions that ‘mimic’ findings commonly associated with SBS,” the trial judge wrote in his ruling, which cited the Edmunds case. “Some of these causes include birth trauma, playground injuries, motor vehicle crashes, and other medical issues.”

Last year, the attorney general of New Jersey announced a conviction review unit to investigate claims of actual innocence, which could offer Heale another chance at vindication. While they wait for Michelle to come home, the Heales are committed to maintaining their family. One of the hardest things to accept, Michelle told The Appeal, is losing “the life that you thought you were going to give your children.”

One of the hardest things to accept, Michelle told The Appeal, is losing “the life that you thought you were going to give your children.”

Mike and Michelle, who have been married for more than 15 years, continue their tradition of, as they call it, “date nights,” now held once a month in a prison visiting room. The twins, who are in fifth grade, visit every other week.

Michelle works with prisoners who are mentally ill, making $7 a day, which she sends home to her children for their savings accounts, according to Michelle. “I need to make somebody’s life a little bit easier,” she told The Appeal of her work. “I need to put a smile on somebody’s face.”

Mike said he tries to focus on what Michelle will be home for, and not the milestones she will miss. He said he has told her, “You’re gonna miss certain things: Sports. And you’re gonna miss high school prom. High school graduation. But what they’re gonna do afterwards, you’re gonna be there. You’re gonna be there for the weddings. You’re gonna be there for the birth of their child. You’re not away forever.”