Michigan Lifers Are Organizing Their Families to Vote

The Adolescent Redemption Project, a new group organized by Michigan prisoners sentenced to life without the possibility of parole, is advocating for progressive prosecutors.

Earlier this year, as COVID-19 ravaged G. Robert Cotton Correctional Facility, Joshua Puckett and his fiancée Cassandra Anzalone hatched an idea.

Puckett, who is incarcerated at Cotton, has been in the Michigan prison system for 25 years. When he was 18, he was convicted of aiding and abetting first-degree murder because he gave directions to somene he knew who carried out a drive-by shooting and later removed a gun from the scene. He was not in the vehicle.

Over the summer, with the November election approaching and issues around mass incarceration gaining steam with voters and leaders alike, Puckett and Anzalone founded The Adolescent Redemption Project, or TARP, a 501(c)4 organization dedicated to ending the mass incarceration of people ages 18 to 25 through political advocacy.

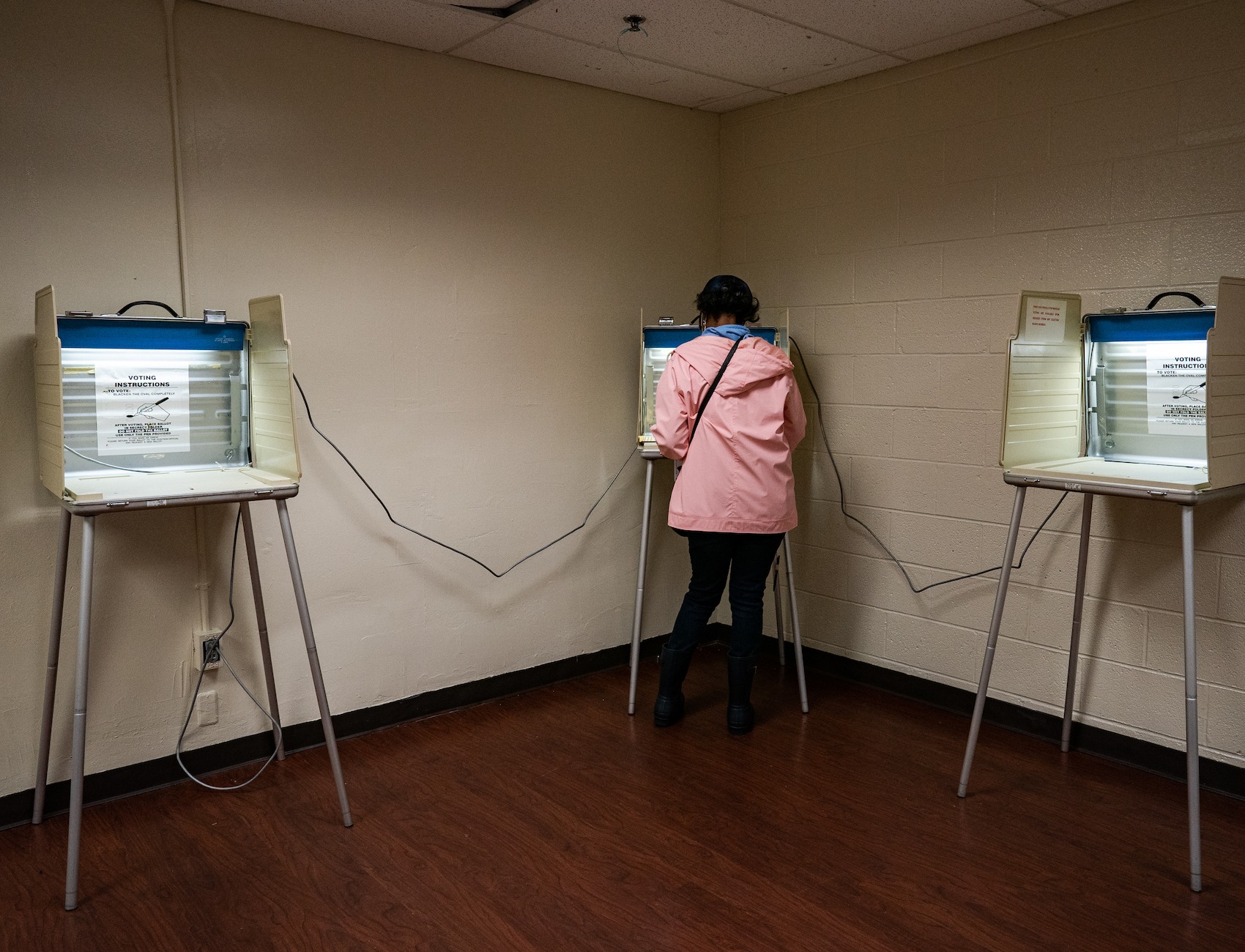

But because the roughly 35,000 people incarcerated in Michigan’s prisons cannot vote, TARP is creating a “voting bloc” of friends and family of incarcerated people who support criminal justice issues and progressive prosecutors.

“If even approx. 20,000 [prisoners] that we got to influence just 2 family members to vote for justice reform progressive candidates we then have 40K votes!” Puckett wrote in an email to The Appeal. “That’s powerful. Prison[ers] have never before had a lobby that moves on their interests.”

TARP estimates that it has spread its “Redemption Voting Bloc” flyers to about 20,000 prisoners since the summer by posting them in dayrooms and on bulletin boards. The flyers use a tear-off form that prisoners can share with their families to register with TARP as part of the “bloc” and receive TARP’s mailings on candidates and issues.

The flyers describe TARP’s mission as “a campaign for mercy,” calling for an end to the “mass incarceration of late adolescent offenders” through eliminating mandatory minimums and allowing judges to retroactively consider adolescent brain development.

The group is also supporting Carol Siemon, a prosecutor running for re-election in Ingham County, which includes parts of Lansing, the state capital. She won handily in 2016, besting three other candidates in the Democratic primary, and she represents a county that votes reliably blue.

Since taking office, Siemon has reviewed life without the possibility of parole cases, beginning with people who committed a crime at age 17 or younger. She said she saw people who had “transformed”—not because of anything the Michigan Department of Corrections had done—but because they found a good mentor, “aged out” of their violent behavior, or they had a child they wanted to see grow up.

“In 20 years, and hopefully sooner, but I say in 20 years, we’re going to look back and say, how did we ever do life for people in prison without the possibility of parole?” she told The Appeal.

In January, Siemon told the Lansing City Pulse about her plans to review and possibly seek commutations for 90 people convicted of first-degree murder serving life without parole. She later apologized after backlash over her comments, saying she regretted not speaking to the victims’ families first.

Still, Siemon has remained true to her philosophy. According to the City Pulse, after Siemon’s election, “nearly all murder defendants have had the chance to plead to a lesser charge [of] second-degree murder.” (Michigan does not have the death penalty.)

“We knew right there we had to support her. If she loses, no other prosecutors will do this kind of work,” Puckett said. Siemon co-wrote a commentary calling for an end to juvenile life without parole and cited the adolescent brain science TARP relies on. She also signed on to a letter committing to reject police contributions and endorsements to her campaign, the only Michigan prosecutor to do so.

“I’ve been a lawyer for 39 years, and I’m really annoyed that the same conversations I was having 35 years ago, we’re still having,” Siemon said, pointing to alternatives to incarceration such as after-school programs and drug addiction rehabilitation.

TARP has also supported Karen McDonald’s candidacy for prosecutor in Oakland County. McDonald won the Democratic primary with 66 percent of the vote, besting incumbent Jessica Cooper, a “tough on crime” Democrat who gained national attention for punishing a 15-year-old Black girl for failing to complete schoolwork while on probation.

The group’s organizing comes amid growing public support for voting rights for formerly incarcerated people, though there is still progress to be made. In 2018, Florida voters approved a constitutional amendment to allow people who served felony sentences to vote again. But in 2019, the state legislature passed a law requiring them to pay all fees before being eligible to vote, effectively disenfranchising thousands, despite questions over its constitutionality. Felony disenfranchisement laws are a Jim Crow relic, but they prevent more than 5 million Americans from voting.

TARP is still new—all volunteers—but its organizers say that it’s growing and empowering incarcerated people. “We’ve created somewhat of a sensation [among] the Michigan prisoners,” said Stephen Silha, a TARP board member. DeAndrea Taylor, one of Breonna Taylor’s sisters, recently joined the board to advocate for their father, Everette Taylor, who has been incarcerated in Michigan since he was 22.

In addition to pushing for change through the courts, TARP is also working on drafting second look legislation, which allows courts to re-evaluate people’s sentences after a significant period of time. Some states have already considered similar legislation, and a version has been introduced in Congress.

“If you can get the legislators to change the law,” said Laurel Kelly Young, Puckett’s attorney and a TARP board member, “things will happen a lot quicker than, like, trying to create precedent to the court.”