A New Jersey Woman Claimed Innocence In ‘Shaken Baby’ Death. Now Her Conviction May Get Another Look.

Spurred by an Appeal investigation into Michelle Heale’s controversial 2015 case, a law professor is asking New Jersey’s Conviction Review Unit to “correct an injustice” and set Heale free.

Michelle Heale was babysitting 14-month-old Mason Hess in 2012, when, according to Heale, his body suddenly went limp. She called 911.

“He has no movement in any parts of his body,” she told the operator. “His whole body is lifeless.”

An ambulance arrived and rushed Hess to the hospital. He died days later.

Police and prosecutors claimed Heale, who had no history of violence, had shaken Hess, causing his death. Heale maintained her innocence, but in 2015, a New Jersey jury convicted her of aggravated manslaughter and child endangerment. When the verdict was read, Heale “was in complete shock,” she wrote to The Appeal.

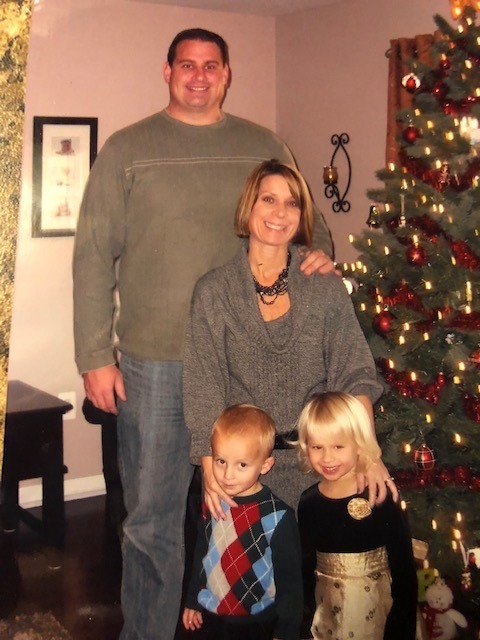

Heale was sentenced to 15 years in prison. At the time, her twins were six years old.

Significant questions about Heale’s guilt have emerged in recent years, spurred by an investigation published in The Appeal in 2020 that tackled the questionable science her conviction had been based upon.

Now, Heale’s conviction may be on its way to getting another look. This week, Colin Miller, a professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law, is submitting an application on Heale’s behalf to the New Jersey Attorney General’s Conviction Review Unit, asking that they “correct an injustice and set Michelle Heale free.” Law student Jasmine Caruthers assisted Miller in preparing the application.

Miller, who is also co-host of the wrongful convictions podcast, Undisclosed, began to investigate Heale’s case after reading The Appeal’s reporting.

“This is one of those cases where forensic science has gone haywire,” said Miller, comparing SBS to the discredited fields of bite mark analysis and microscopic hair comparison. False or misleading forensic science has contributed to more than 700 known wrongful convictions since 1989, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

Former New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir Grewal created the conviction review unit in April 2019. Since its inception, the unit, which is headed by former prosecutor and family court judge Carolyn Murray, has exonerated just one person, Taron Hill. Hill was wrongfully convicted of murder in 2006 and was released in July. Over 450 applications have been submitted to the unit, according to the attorney general’s office, each involving a potential miscarriage of justice. Nearly 200 of those applications are in the screening process, and another 95 are awaiting screening. Nineteen applications are “currently under active re-investigation.”

Hill is one of 43 people who has been exonerated in New Jersey since 1989, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. Heale’s supporters hope she will soon be added to that list.

At Heale’s trial in 2015, the prosecution relied on evidence that, at worst, has been discredited, and at best, remains highly contested.

Shaken baby syndrome, also known as abusive head trauma, is a theory first developed in the 1970s. Proponents claim that shaking a baby produces a so-called “triad” of catastrophic injuries exclusive to victims of SBS — subdural hemorrhage, retinal hemorrhage, and brain swelling. No other injuries, such as bruising or grab marks, need to be present for the diagnosis. The shaking is so violent, medical experts often testify, that the person last with the child must be the one responsible.

But studies — and a growing number of exonerations — have challenged the tenets of SBS.

“The imprimatur of that incorrect medical conclusion has led not only to wrongful convictions, but also a cascade of collateral harms: decades of incarceration or even imposition of the death penalty, the shattering of families,” said Laura Cohen, a Rutgers University law professor and co-founder of the New Jersey Innocence Project, in an email to The Appeal.

In a 2016 literature review, researchers examined 1,065 studies on SBS in an attempt to determine if shaking, with no external injuries, produced the triad of injuries. In total, 1,035 of those studies were excluded because they had examined fewer than 10 cases. The review didn’t identify a single SBS study that could be characterized as “high quality,” noting that most studies were unable to confirm whether subjects had been the victims of abuse.

A separate study, published by the Belgian Neurological Society, concluded that, contrary to expert testimony common in SBS cases, there are no retinal hemorrhages that are only present in abusive head trauma cases.

“[SBS] has never been validated,” said Keith Findley, co-founder and president of the Center for Integrity in Forensic Sciences and co-founder of the Wisconsin Innocence Project. While defenders of SBS often point to their clinical experience to support their diagnoses that shaking causes the triad, “that doesn’t confirm the shaking is the cause,” said Findley. “It just confirms that they call it the same thing every time.”

Courts, too, have become skeptical of prosecutions based on the SBS triad. In the summer of 2018, about two months after the state Supreme Court refused to hear Heale’s appeal, a trial court acquitted Robert Jacoby of aggravated assault. New Jersey prosecutors had claimed Jacoby had shaken his approximately 11-week-old son. But Jacoby maintained that his baby had unexpectedly vomited and gone limp, at which point he’d taken him to the hospital.

“It is now well established and widely accepted in the scientific community that there are other alternate causes or conditions that ‘mimic’ findings commonly associated with SBS,” the trial judge wrote in his ruling.

In Heale’s case, the prosecution’s medical experts told the jury that illness or an accidental fall — both of which Hess had experienced shortly before his collapse — could not have contributed to Hess’s death.

Alex Levin, then chief of pediatric ophthalmology and ocular genetics at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, testified that the injuries to Hess’s eyes provided a textbook example of the effects of shaken baby syndrome. The only other possible cause of the injuries, Levin claimed, was if “a television or something crushed his head, unless he was killed in a car accident, unless he fell 11 meters.” The prosecutor asked another witness, Lucy Rorke-Adams, then a neuropathologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, if there was any doubt that Hess had been shaken to death. Rorke-Adams replied, “No.”

Both Levin and Rorke-Adams have testified for the prosecution in SBS cases where the accused was later exonerated.

Contrary to testimony from the state’s experts, there were other viable explanations for Hess’s death, according to The Appeal’s 2020 investigation.

The day before Hess collapsed, he threw up at Heale’s home. His mother took him to the pediatrician, who diagnosed him with ear and upper respiratory infections, and prescribed antibiotics. His mother, who’d been friends with Heale for several years, offered to keep him home.

“R u sure i don’t want to get any of you sick,” she texted Heale. “Won’t be the first time, won’t be the last time. Everyone will be fine,” Heale replied.

When Hess was rushed to the hospital from Heale’s home, the emergency room doctor diagnosed him with pneumonia.

Hess had also suffered a fall at home about a week before his collapse, his parents testified. In the autopsy report, the medical examiner noted there was a bruise on his forehead.

“Mason just walked into the sliders… think the bump now looks bigger. Leaving the screen on now!!!” Heale texted Hess’s mother the day before his collapse, according to court documents. “Lol unreal,” his mother replied.

Several studies have concluded that symptoms once thought to be exclusively associated with SBS can be caused by something as simple as a short-distance, accidental fall. There can also be a delay between the fall and a child’s collapse or death, according to several case examples Miller cites in Heale’s application.

“You can have cases where initially everything appears okay and then it’s only later when you realize the impact this had,” said Miller.

Before Heale’s trial began, her attorneys contacted Chris Van Ee, a biomechanical engineer and accident reconstruction specialist. Van Ee prepared a report and emailed it to her attorneys, but never heard back, according to Heale’s application. In his report, Van Ee wrote that external injuries would be present on Hess if Heale had violently shaken him. “There are no reported skull fractures, bruises, or other injuries to indicate that Mason was abusively shaken with great force or otherwise assaulted,” he wrote. But his report was never presented at trial.

“There was an expert — the leading expert — ready, willing, and able to testify,” said Miller, adding that Van Ee’s report presented evidence that Hess’s death was “far more likely” caused by a short fall than by shaking.

“Shaken baby syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion, not inclusion,” said Miller. “This is something that certainly cannot be excluded as the cause of death.”

In many SBS cases, medical professionals and law enforcement dismiss evidence that supports alternate explanations for a child’s death, said Jessica Henry, a professor at Montclair State University and author of the book, “Smoke But No Fire: Convicting the Innocent of Crimes that Never Happened.”

“Once folks come in with this notion that the child is dead because there must have been some kind of abusive act, they stop focusing on the rest of the medical evidence that would suggest otherwise,” said Henry.

Heale hopes the attorney general’s office will review “all the facts of my case” and “recognize that I am not the woman portrayed by the prosecution,” she wrote to The Appeal.

Heale stays in touch with her twins, now 13, through phone calls, emails, and occasional visits. Before the pandemic, she saw her children two or three times a month, but over the last two years, she’s gone for months at a time without seeing them.

“Physically being away from my children and husband is the hardest part of being incarcerated,” Heale wrote to The Appeal. “Nothing can replace being home and involved with them on a day to day basis.”

Even as her faith in the legal system has deteriorated, Heale has tried to remain optimistic, buoyed by the support of her family and friends. On the first day of the month, she wrote, “Happy February…another month closer to home!”