LA is Locking Up More Mentally Ill People, Despite Diversion Efforts

In 2015, Los Angeles County created a program to reduce the number of mentally ill people trapped in jail. But since then, the number of people with mental illness incarcerated in LA has instead increased significantly.

This story is the first in a series on the mental health crisis in Los Angeles County jails. The articles were produced in collaboration with the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

In 2015, Los Angeles County created an Office of Diversion and Reentry to keep people with mental and physical health needs out of the county’s jails. Upon creating the program—which connects people with mental health needs to supportive services instead of jail—county officials trumpeted it as a new era for justice in the most populated county in the United States.

“Our priority is to expand diversion services that work, like mental health, like drug abuse treatment and housing to keep vulnerable individuals out of the criminal justice system,” former supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas said on the day the county created the office.

But since then, the number of people with mental illnesses in the county’s decaying, overcrowded jail system has instead increased significantly, according to data obtained by The Appeal.

The numbers suggest that Los Angeles County has so far failed to rise to the standard it set for itself more than seven years ago. Data from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD) shows that in 2015, more than 3,700 people with mental illnesses were locked up in county jails. By 2022, that number increased to almost 5,700. In that time, the total jail population decreased from roughly 17,000 to 13,800—which means the share of people with mental illness in the jail system rose from about 22 percent to 41 percent in that time period.

Seven community activists, mental health professionals, and attorneys who spoke with The Appeal said the number of incarcerated people experiencing mental illnesses has grown because of the county’s longstanding failure to adequately invest in resources that could prevent people from coming into contact with the criminal legal system in the first place—like affordable housing, mental health care, youth programs, and job opportunities.

That decadeslong lack of care has ballooned into the situation Los Angeles is experiencing today, where the number of people experiencing mental health issues is rising and more people are becoming unhoused. At the same time, advocates say the county’s jail system has become decrepit, dangerous, and unfit to house anyone—let alone people with mental illness.

“We are reaping what the county has sowed,” said Ivette Alé-Ferlito, executive director of La Defensa, an intersectional feminist organization that works to divert funding out of the criminal legal system and implement alternatives to incarceration. “It’s a reflection of the state of the county and the world in terms of the impacts of sustained trauma and generational divestment from supportive services. Families grow more and more fractured. More and more people are being displaced. And things that would actually ensure healthy communities are not being funded.”

While the creation of the Office of Diversion and Reentry has been a major step forward for the county, experts say it is not being funded at the pace of the problem. The office has successfully gotten thousands of people with mental illnesses out of jail, but absent significantly more funding or fewer arrests, the number of incarcerated people suffering from mental illness will likely continue to rise. Los Angeles County’s most recent adopted budget was $44.6 billion. The Office of Diversion and Reentry accounted for around half a percent of that.

“The Office of Diversion and Reentry does an incredible job getting people out, but they don’t stop the flow of people going in,” said Mark-Anthony Clayton-Johnson, the executive director of Dignity and Power Now, a grassroots organization that supports incarcerated people and their loved ones. “The only thing that will do that is community beds and community treatment that is not rooted in this carceral logic.”

In a written statement, a spokesperson for Los Angeles County said that it has invested heavily in solutions to reduce the number of incarcerated people with mental illness. The county stated that ODR is just one of several programs and departments that provides services to residents in need and noted that the county is obligated to fund various programs at appropriate levels.

“Measuring only ODR’s $280.3 million annual budget as a percentage of County spending ignores the hundreds of millions in additional funding for individuals experiencing homelessness, many of whom suffer from mental illness, for example,” the County of Los Angeles said in an emailed statement. “It is also worth noting that ODR had for many years struggled with a structural deficit that we were finally able to close last year through the budget process with an infusion of $20.6 million. In total, we increased ODR’s budget by $109.6 million, a 64% increase.”

In a separate written statement, the sheriff’s department, which oversees the county’s jail system, said that it is committed to working with other county agencies, improving the safety and security of incarcerated people, and providing a constitutional level of care.

“We support the efforts of ODR and other partners in seeking solutions for appropriate placement in our communities while balancing public safety,” the department said. “Our jails and our population have seen changes over the last few years requiring an even greater focus on our increasing mentally ill population.”

Los Angeles County is home to the largest jail system in the country, with more than 14,000 people incarcerated in the county jails in 2022. Nearly half of them are being held pretrial, meaning they have not been convicted of a crime. The jails have been called a human rights disaster by advocates and jail staff alike, and the appalling conditions inside the jails—including a lack of mental health care, excessive force complaints, and suicides—prompted the Department of Justice to put the jail system under a mandatory federal monitoring program in 2015.

That same year, the county’s Board of Supervisors created the Office of Diversion and Reentry (ODR) with a goal to keep people experiencing mental illness, substance use issues, or houselessness out of jail. ODR uses several different programs to divert people from jail. One program connects pretrial detainees with permanent supportive housing, case management services, and treatment. Other programs take people who have been found incompetent to stand trial out of jail and place them in community-based care, which ranges from acute inpatient treatment to open residential services.

Since its creation, the office has been extremely successful. One 2019 report by the RAND Corporation found that of a group of 96 participants, 74 percent remained stably housed after one year and 86 percent had no new felony convictions.

But while ODR helped the people it could on a relatively shoestring budget, conditions in the jails remained poor, and the county continued to lock up more people with mental illnesses. In an attempt to reduce the county’s reliance on jails, the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors in 2019 adopted a “care first, jails last” approach to public safety and established an Alternatives to Incarceration Work Group. The following year, the committee published a report with 114 recommendations detailing how the county could reduce its reliance on incarceration and instead invest in community care. But in the three years since the group released its proposal, little progress has been made.

“That roadmap has been in the county’s hands since March of 2020,” said Alé-Ferlito from La Defensa. “We’re coming up on three years and we’ve seen very little traction in actually moving the implementation of these recommendations.”

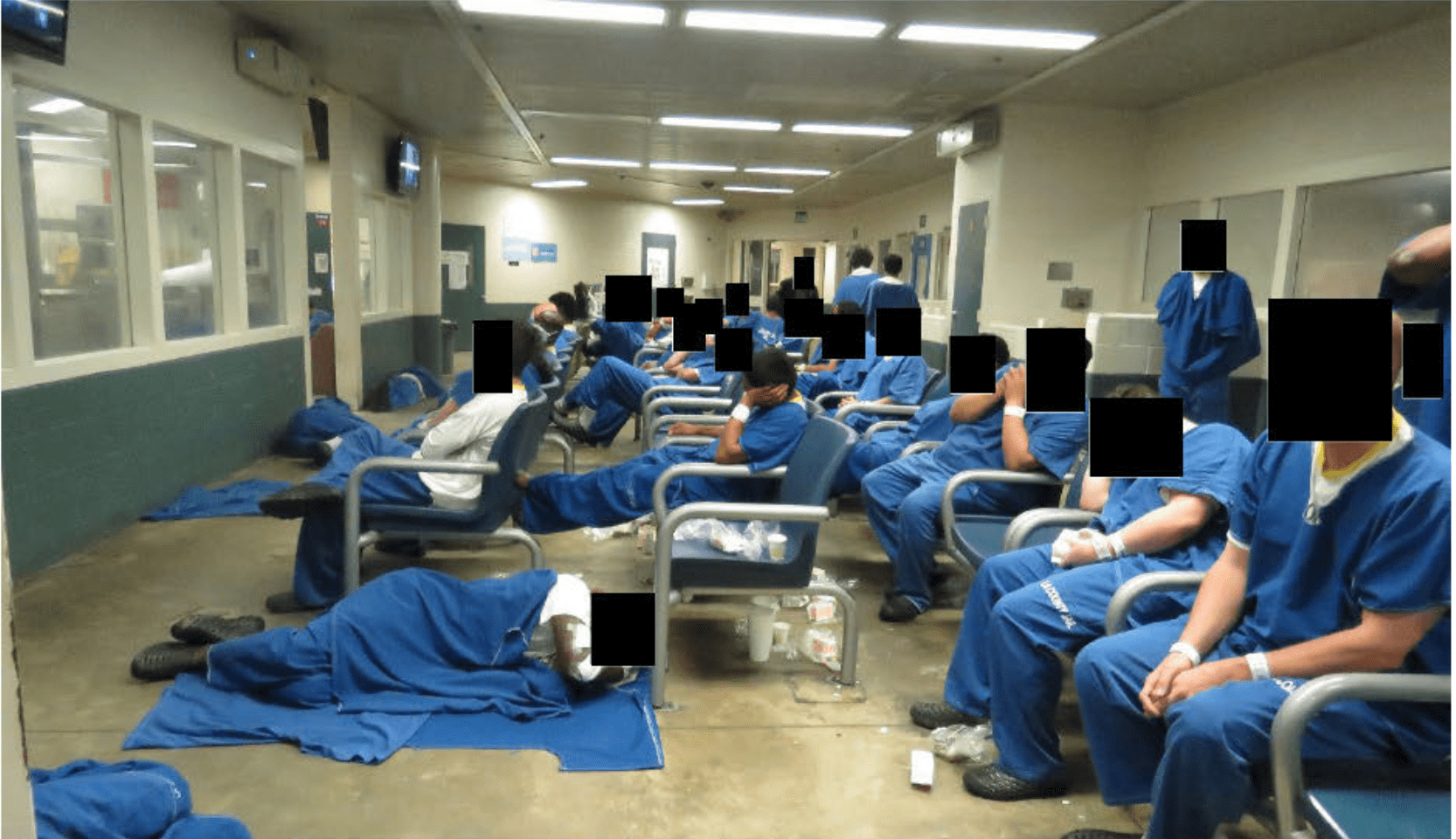

In 2021, the county voted to close one of its jails—the squalid and overcrowded Men’s Central Jail (MCJ). But officials have slow-walked closing that facility too. In September 2022, the American Civil Liberties Union filed an emergency motion stating that the jail system’s main booking location, the Inmate Reception Center, was so overcrowded people were being chained to chairs for days at a time and forced to urinate and defecate on themselves.

“Everyone is on edge because it is crowded, we can’t sleep, deputies treat us like we are subhuman,” Diego Bolton, an incarcerated person, told the ACLU in a sworn statement. “Everywhere in the area there is blood and pee on the floor and people have to sleep on the floor.”

After the ACLU filed its motion, the sheriff’s department opted to reduce overcrowding and long wait times at the booking center by moving people from the booking center to other facilities.

Those sites include MCJ—even though the county has agreed to close it, said Melissa Camacho, senior staff attorney at the ACLU of Southern California. According to data from the LASD, as of February 24, almost 3,600 people were being held inside Men’s Central Jail—nearly 70 beds over the jail’s recommended capacity.

Camacho said that when she visited the central booking center last summer, she witnessed people peeing in cups and laying in puddles of urine. In addition to the unsanitary conditions, she said it’s likely people with mental health needs are going weeks or months without seeing a psychiatrist or getting medication.

“If they were on medication up to the point of arrest and booking, they may be taken off cold turkey and left off for weeks and months,” Camacho said. “You can imagine the deterioration those people experience.”

On Tuesday, the ACLU filed a motion asking a judge to impose sanctions on the County Board of Supervisors and the sheriff and to find them in contempt of court for failing to comply with a court order requiring them to address the appalling conditions at the booking center. The motion states that jail staff have been tethering people with mental illness to gurneys and have repeatedly failed to provide people in the intake center with the medications they were prescribed prior to being arrested.

“After almost five decades of an endless cycle of promises followed by excuses and failures, and generations of class members enduring abysmal conditions, the time for talk is over,” attorneys for the ACLU of Southern California wrote. “While the Board [of Supervisors’] inaction means there is a dire shortage of community beds and treatment for people with serious mental illness, there continues to be no shortage of these same people suffering inhumane conditions in IRC day after day.”

The county has not yet responded to the motion in court.

Advocates say solutions are within reach and question the county’s reticence to fully fund ODR when the program has been so successful.

A 2020 report by the RAND Corporation estimated that more than 60 percent of the jail’s mental health population—over 3,300 people—could be diverted from jail. ODR hit its maximum capacity of 2,200 beds in 2021, and the office was forced to turn away people it could have helped divert from jail. Last October, the board of supervisors agreed to fund an additional 750 beds—a far cry from the number of beds needed to close Men’s Central Jail.

“You never hear of us running out of jail beds,” said Liz Sutton, a licensed clinical social worker who runs a program that helps get incarcerated people with mental health needs released into outpatient care. “The money is going to incarcerating people, so that’s where people end up. We need money to go to mental health care, we need more psych beds, we can’t staff programs to the extent necessary because there isn’t enough funding.”

Los Angeles County allocated nearly $214 million from its general fund to ODR’s budget in its 2022-2023 Final Budget. In comparison, the county gave nearly $3.6 billion to the sheriff’s department from that same funding source—nearly 17 times that of ODR and about 8 percent of the entire county budget.

The Appeal gathered data on every settlement the county made that involved the sheriff’s department in the 2022 calendar year. A review of that data shows the county spent nearly $84 million—more than a third of the money the county gives ODR—settling lawsuits against the LASD. Additionally, data from Los Angeles County litigation reports shows that the county has spent nearly $400 million on lawsuits involving the LASD between fiscal years 2014 and 2020.

In one of those cases, sheriff’s deputies violently restrained, tasered, and punched a man named Eric Briceno, killing him. Briceno was in the midst of a mental health crisis when his mom called for help. In another case, the county paid the family of Rufino Paredes $1.9 million after Paredes died by suicide in a county jail.

“There seems to be unlimited money for settlements over people who die in custody, but not for programs that would reduce overcrowding and make deaths less likely,” said Camacho of the ACLU.

So far this year, the sheriff’s department says four people have died in its jails. In 2021, 55 people died in custody—a rate of about one death per week, according to a report from the Office of the Inspector General, a county agency tasked with overseeing the jails.

“We just don’t have the correct view of the emergency situation that exists,” Camacho said. “This isn’t OK if it persists while we work slowly to get rid of it. This is urgent. People are dying on their watch.”

This story previously stated that the Office of Diversion and Reentry did not respond to requests for comment. After publication, a spokesperson for Los Angeles County clarified that the Office of Diversion and Reentry contributed to the county’s statements for this story. This story has been updated to reflect that.