L.A. County’s Jail Booking Center Has Become a ‘Living Hell,’ Detainees Say in Court Filing

County officials agree that conditions have deteriorated at L.A.’s Inmate Reception Center. But they’re resisting calls for substantive change.

Inside the Los Angeles County jail’s booking center, people with severe mental illness are chained to benches or chairs for days on end, often forced to defecate and urinate on themselves, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) alleged in a filing submitted in federal court last week.

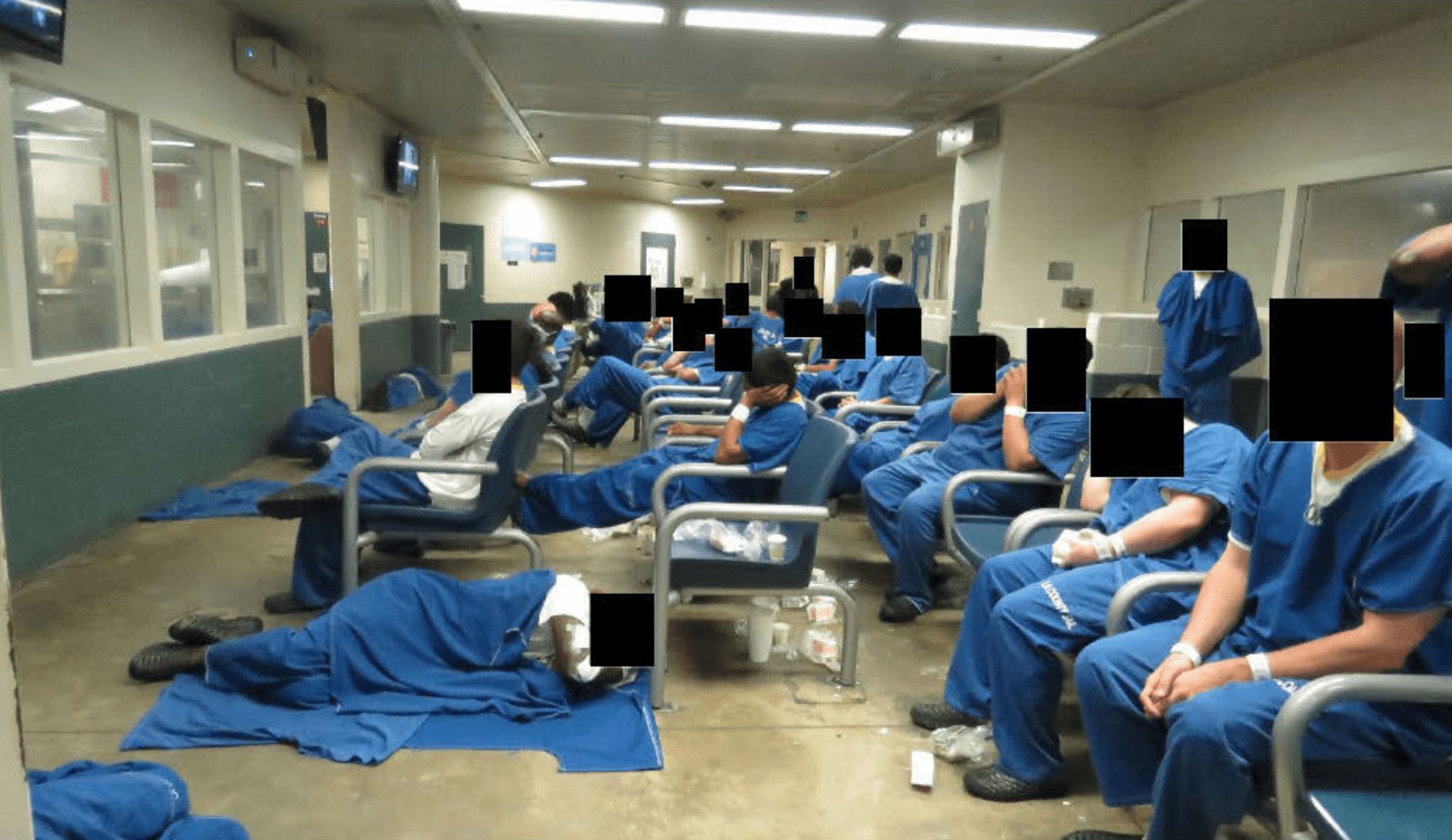

The Los Angeles County jail system’s Inmate Reception Center (IRC) has become so overcrowded that detainees are left to sleep on the ground, most of them without blankets, according to the ACLU. The floor is covered in garbage and urine. The men are denied showers and clean clothes. The toilets are clogged and smeared with feces.

“It is a living hell in here,” Gilberto, a detainee, told an ACLU attorney who visited in August. Gilberto, who has asthma, said that since he’d arrived at the IRC four days earlier, he had not been given an inhaler, which he typically uses three to four times a day. “The deputies treat us like animals and don’t give two shits about us.” (The Appeal is only using detainees’ first names to protect their privacy.)

Gilberto’s sworn statement is among a set of interviews and observations the ACLU submitted to Federal District Judge Dean D. Pregerson on Thursday, following visits last month to the IRC by attorneys with the ACLU’s National Prison Project and the ACLU of Southern California.

The ACLU is asking the court to order Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva and the County of Los Angeles to limit custody at the IRC to no more than 24 hours and to ensure detainees are held in sanitary conditions with access to drinking water, working toilets, and medical care. The filing argues that the county should be compelled to act under the terms of a 1975 class-action lawsuit that successfully challenged rights violations at the Los Angeles Men’s Central Jail.

Each year, tens of thousands of men entering the Los Angeles County jail system—the largest in the country— are processed at the IRC before being sent to another facility. Detainees are supposed to spend less than 24 hours at the booking center, but in recent months people have been held there, in inhumane conditions, for more than a week, according to the ACLU.

On Monday, the county and sheriff’s office filed their response to the ACLU’s allegations and agreed that conditions inside the IRC “have deteriorated dramatically in past months.” However, they opposed the ACLU’s request for a 24-hour cap on detention. Instead, they proposed a limit of 36 continuous hours in only the clinic area, where nurses conduct medical screenings for new arrivals. This would not apply to people in holding cells. In a reply submitted to the court on Monday night, the ACLU reiterated the need for a 24-hour limit for everyone held at the booking center.

The county and sheriff say conditions at the IRC have worsened because the facility “has been overwhelmed with new inmates entering” the jail system, including a “skyrocketing number” with serious mental health conditions. These detainees require specialized housing, known as Moderate Observation Housing or High Observation Housing, both of which have been “in short supply,” they told the court.

The county and sheriff say they’ve already begun to address this issue by double-bunking detainees with mental illness who had previously been held alone in two-person cells. They’re also converting more county jail beds to mental health beds.

In an email to The Appeal, the sheriff’s office said they could not comment on pending litigation. The County Board of Supervisors did not respond to requests for comment.

The reversal of a zero cash bail policy for most misdemeanors and low-level felonies has also contributed to a “surge” of people churning through the IRC, according to the response from the county and sheriff.

The Los Angeles County Superior Court instituted a zero cash bail policy in April 2020, at the start of the pandemic. The number of people being processed through the IRC quickly fell by nearly half, from about 86,000 in 2019 to about 45,000 in 2021. The policy “had a profound effect on the county’s overall jail census,” the county and sheriff told the court.

Since the reversal of the bail policy in July, the number of people coming through the booking center “approximates the pre-pandemic 2019 pace,” according to the county and sheriff.

The county could reduce the number of people entering the jail system by voting to implement and make permanent the zero cash bail policy, Corene Kendrick, deputy director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project, told The Appeal. With more than 14,000 people currently detained in Los Angeles County jails, the system is operating almost 20 percent over capacity. (The county and sheriff told the court that while there is a bottleneck at the IRC, overcrowding is not an issue at other facilities.) Nearly half of all people held in the Los Angeles County Jail System are awaiting trial and are presumed innocent.

Kendrick also urged the county to provide adequate funding for community-based programs that serve people with mental health disorders. A 2020 study commissioned by the county found that over 60 percent of detainees with mental illness could be safely placed in community programs if they existed and had the necessary resources.

The ACLU has asked the court to order the county to justify why it has failed to adequately fund “programs to provide an additional 1000 beds in the community for people with mental illness who would otherwise be in the Jail.”

During Kendrick’s visit to the IRC in June, she reported seeing nine men chained to chairs. Several appeared to be detoxing, and at least two people appeared to be “floridly psychotic or disassociating, speaking to themselves or others only they could see,” she wrote in her declaration to the court. In the past month, some people have been chained to chairs for almost seven consecutive days, according to the ACLU.

The ACLU is requesting a four-hour limit on the time a person can be chained, but the county and sheriff oppose a cap and have defended the practice. In their response to the court, they claimed that individuals “tethered” to “cushioned chairs” had been identified as “high risks for engaging in a suicide attempt or self-directed violence,” or were “acting out due to mental illness or intoxication.”

When the ACLU visited the IRC in August, people with mental illness told attorneys they were rapidly unraveling.

Chuck, who has bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, told an ACLU attorney that he hadn’t received any of his medications since he’d arrived at the booking center days earlier. He was afraid to eat the food because “voices say to me it is poisoned.”

“I have been crying on and off since I have been here,” he said. “I was thinking about suicide but don’t want to tell anyone because if I do they will chain me to [a] chair.”

A 61-year-old man said he had defecated on himself, but wasn’t allowed to shower. Since arriving at the IRC, he said he hadn’t been given his medication for depression or paranoid schizophrenia. He repeatedly asked to see a mental health specialist, but was told he couldn’t see one until he was transferred to another facility. “Throughout the day, I will break out into tears,” he wrote in a statement submitted to the court.

Another man described being put in a holding cell on his first night with 40 to 50 other men, packed in like sardines. “We only got out when we started screaming, kicking the windows and threatening not to eat,” he told an attorney with the ACLU. Since arriving, he said he had not received his psychiatric medication for depression, leading him to “feel despair.”

“This is cruel and inhumane,” he said. “No human should be treated this way.”