Jeff Sessions Left Behind a Record-Breaking Gun Prosecution Machine

The program was supposed to target ‘leading’ violent offenders. Today it’s sweeping up low-level, and disproportionately Black, defendants.

On the evening of Nov. 30, 2015, Adarius Montrells Sims of Birmingham, Alabama, was driving his gold Grand Am home. Tired after hanging out all night, he fell asleep at the wheel. The car crashed, and medics found Sims unconscious. After the crash, a police officer peering into the wreck spotted a .40 caliber pistol on the passenger-side floorboard. Police ran Sims’s name and saw he had two prior marijuana possession convictions, a record that made that gun illegal in Alabama.

But Sims hadn’t hurt anyone and his record was nonviolent. So he was sent to a gun court rehabilitation program, paying fines, and taking classes on anger management. While taking part in the program, he met with a federal agent from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, who told him that he could still face federal charges despite the local gun program he was agreeing to.

“I had told him I was doing gun court, but he was saying they overrule all of that, and if they wanted me they could get me,” Sims recalls. “But he said they weren’t going to. I don’t got a violent history.”

Over the next two years, this apparent promise of discretion seemed to hold. No other charges from the incident were brought and Sims began to move on. The father of two got a new construction job, and his girlfriend became pregnant.

Sims had no idea, however, that thousands of miles away in Washington, D.C., the new Attorney General Jeff Sessions was reversing the previous administration’s course on federal gun charges, which had dropped steadily throughout the Obama era. Focused on what he called the nation’s “rising tide of violent crime,” Sessions wanted to prosecute more gun cases to deter those he deemed most likely to commit violent crime: people with guns and felony records.

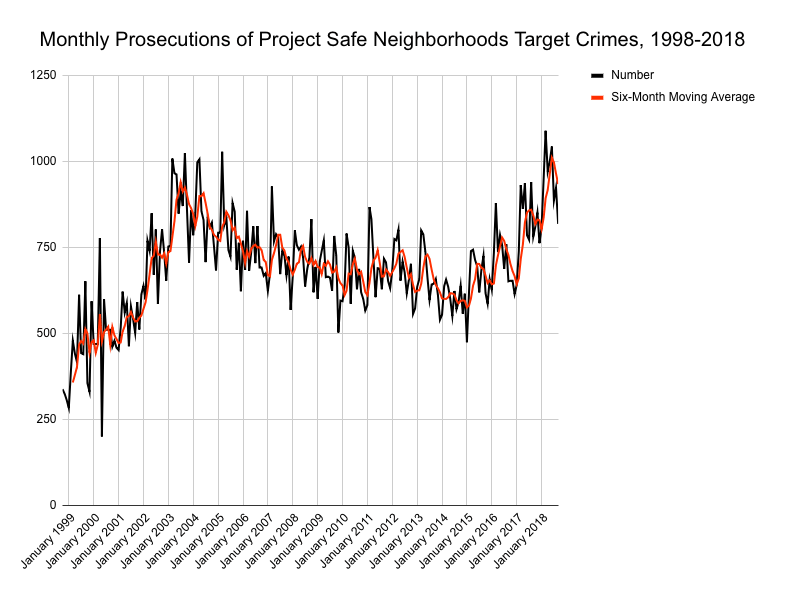

In March 2017, only a month after assuming his post, Sessions announced his game plan. He ordered all federal prosecutors nationwide to prioritize firearm prosecutions, especially for illegal possession. Federal prosecutors would be evaluated by their commitment to such tactics, Sessions announced later that year, as part of a reinvigorated Department of Justice program, known as Project Safe Neighborhoods. A few months after his initial call to action, federal gun prosecutions ramped up by 23 percent. In the first half of 2018, attorneys who worked under Sessions took on more firearms cases than any previous administration in the same time period.

Since Trump took office, federal prosecutors’ gun caseloads, adopted from cops and county prosecutors below, have risen to a rate never before seen.

This widened net eventually caught Sims. Sometime around May, while working on a construction site, Sims got an angry call from his father. Federal agents had come to his father’s apartment looking for him. He didn’t know why. He cooperated and had them pick him up at work. Only then did he realize he was again facing charges, this time from federal prosecutors, for the same gun found in his crashed car over two years ago. The next month, Sims pleaded guilty to felon gun possession. He will be sentenced in January on a charge that carries about five years in federal prison on average. (A local conviction for felon gun possession may only result in probation time, especially in states with permissive gun laws.)

At President Trump’s request, Sessions resigned from his post this month. But he’s left in place a formidable assembly line that transfers low-level gun cases from counties nationwide to federal prosecutors. That assembly line, which Sessions called his “centerpiece” crime reduction initiative, is still processing thousands of people across the country, with no sign of slowing.

In his resignation letter, Sessions alluded to the program as one of his major achievements, boasting that, under his watch, U.S. attorneys “prosecuted the largest number of violent offenders and firearms defendants in our country’s history.” And most observers expect that this tough-on-crime model, which Trump praised during his 2016 presidential campaign, is likely to remain a DOJ priority.

How it works

The initiative has federal prosecutors adopt ongoing gun cases from local police and prosecutors, or mine local court dockets for already adjudicated cases involving guns. The resulting federal sentences are generally longer and can send people to federal facilities far from home.

The punishment banishes “leading violent offenders” from their support networks and isolates them in long-term imprisonment. The combined damage is supposed to serve as a powerful deterrent.

Sessions explained the underlying logic during his Senate confirmation hearing. “Criminals are most likely the kind of person that will shoot somebody when they go about their business,” he said. “And if those people are not carrying guns because they believe they might go federal court, be sent to a federal jail for five years, perhaps they’ll stop carrying those guns during that drug dealing and their other activities that are criminal. Fewer people get killed.”

Despite Sessions’s departure, the data suggest that local law enforcement in certain parts of the country have responded enthusiastically to these calls. Since Trump took office, federal prosecutors’ gun caseloads, adopted from cops and county prosecutors below, have risen to a rate never before seen.

And, as with previous administrations, a majority of these gun charges are hitting Black defendants. In fiscal year 2017, for example, 53 percent of defendants, convicted of felon in possession firearms, were Black. Such disparities have held constant throughout the years.

The prosecution pipeline

On the morning of Sept. 24, the ballroom of the Wynfrey Hotel in Hoover, Alabama, was packed with prosecutors. They had flown in from across the country to hear Sessions discuss his vision for combating violent crime. Sessions, who aggressively prosecuted gun cases during his stint as a U.S. attorney in Alabama, rallied the troops, insisting that their work was helping to combat the slight uptick in violent crime seen in 2015 and 2016.

“We’ve charged the most federal firearms prosecutions in a decade, and we’re not just putting people in jail, our efforts are bearing fruit,” Sessions declared, crediting the program for preliminary data showing a 2017 drop in violent crime.

Seated next to Sessions that day was Jay Town, Northern Alabama’s 45-year-old U.S. Attorney. Like Sessions decades ago, Town has made a name for himself by zealously carrying out Washington’s gun prosecution agenda, an approach that regularly earned him the former attorney general’s praise.

Of all 94 U.S. attorney districts nationwide, Town’s Northern Alabama office is among the top 20 (raw and per capita) for the violent crime prosecutions Sessions prioritized in March 2017, 94 percent of which are gun cases. (Most of the districts topping the list are also in the South.)

To achieve these numbers, Town has built a prosecution pipeline, routing cases from local law enforcement all across Northern Alabama to his office. Last year Town met with all 27 county-level prosecutors in his district, and instituted a program streamlining the process by which county prosecutors can refer gun cases to his office. At the same time, Town has been working closely with the ATF, which has been taking over cases after local police encounter residents with guns and felony records.

In May, for example, under the mantle of Project Safe Neighborhoods, Town announced the arrests and indictments of 71 people on gun charges, saying that local prosecutors had brought him their most serious gun cases. “We asked them to bring us their worst cases, bring us your trigger pullers,” Town told local media, which proceeded to publish the mug shots of numerous defendants, almost all Black.

The indictments from the gun roundup, however, suggest that many of the defendants were stopped randomly for low-level infractions. Town’s office published the names of 46 of the 71 people. But only a handful were charged federally because of gun offenses that indicated serious violent intentions, such as the production of a firearm silencer. Most cases stemmed from run-of-the-mill police operations, such as controlled buys, traffic infractions, or responses to residents’ calls about suspicious activity.

Although many of these cases are low-level and sometimes based on random police encounters, Town has said that authorities are going after top targets, based on prior intelligence. “The defendants that we’re prosecuting, we’re not always going to get them for their worst offenses,” he said to local media in October. “But they are our worst offenders.”

But several Alabama police officers and prosecutors working on the program with Town’s office told The Appeal that federal prosecutors seem to be accepting a wide range of everyday gun offender cases, rather than targeting select people.

Christina Kilgore, chief deputy district attorney of Talladega County, said her office sends gun cases federal whenever an opportunity presents itself. If a defendant has a felony history and is caught for possession, she said in a phone interview, either local police will send it to the ATF, or her office will refer it to federal prosecutors. “I don’t know what other factors anyone’s considering,” she said, “We don’t have an agenda as to which we’re picking and which ones we’re not picking.”

You have to make people feel safer, that’s the reason these guys are carrying guns.

Andrew Papachristos a sociology professor at Northwestern University

Similarly, a police officer, who requested anonymity citing fears of professional reprisal, said that he sees his department referring all gun cases that they can to federal law enforcement authorities, like the ATF.

“There are people who should never see the light of day again, but there are also people who made a mistake years ago, but are law abiding and now need a gun for protection,” the officer said. “There’s no distinction between those two types. It bothers a lot of people in law enforcement.”

This wide net is being cast, they say, because federal prosecutors have not given locals targeted guidance for when to send cases federal. According to one prosecutor, who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak on the subject, federal prosecutors are just taking cases whenever it means more time. “Nobody has asked what’s the criteria for the ‘worst of the worst.’”

The program is just “chasing numbers,” said another prosecutor, who requested anonymity citing fears of professional reprisal. “The message is ‘target,’ but what they do is ‘net.’”

The Department of Justice did not respond to request for comment about these criticisms of Project Safe Neighborhoods.

‘Make people feel safer’

Sessions’s model for combating gun violence is premised on the idea that the fear of incarceration and exile will compel people to put down their guns. But the program’s design does not address the social conditions that cause people to carry, argues Andrew Papachristos, a sociology professor at Northwestern University whose work focuses on gun violence.

The irony of the program’s target selection “is that the group most likely to be victimized is most likely to carry guns,” Papachristos notes. “You have to make people feel safer, that’s the reason these guys are carrying guns.”

Living in public housing, Sims said he saw people getting robbed at night or caught in crossfire, and felt he needed protection.“Until I was grown I didn’t need to have a gun,” he said. “I was a sports guy, but as I grown up and got kids, I needed to protect them.”

Gun violence is concentrated in West Birmingham, the poorer and overwhelmingly Black side of the city. Several men with felony records in Ensley, one of the west side’s neighborhoods, told The Appeal that they understood the risks of carrying guns but choose to carry anyway because of day-to-day dangers they face.

Of all major American cities, Birmingham had the fourth-highest murder rate per capita from August 2017 to July 2018. Its murder rate during that period, 43.35 murders per 100,000 residents, is higher than New York City’s at the height of the crack epidemic. And as of 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Alabama ranked second highest in the country for gun deaths per capita.

Surveys in other high-violence cities have similarly found that people say they need illegal guns for safety and are not deterred by the potential criminal consequences.

A recent Urban Institute survey of hundreds of young adults in high-crime pockets of West Side and South Side Chicago found that the vast majority of male gun holders said they carried to protect themselves, friends, and family, not for economic or status motivations. Ninety-eight percent of these respondents said they knew someone who had been victimized by gun violence in the past year. And men who had been shot or shot at in the past year were 300 percent more likely to report that they had carried a gun at some point, the researchers found.

Given this high exposure to violence, the threat of law enforcement punishment for gun possession did not register very highly to respondents. Less than 16 percent of gun holders surveyed felt that police were likely to catch someone for holding guns, or even shooting at someone. And even if they knew they were going to be arrested, only 27 percent said this guarantee of punishment would make them less likely to carry.

The omission of this reality may help explain why the model’s effects on violent crime historically have been fairly minimal, argues Alex Vitale, a sociology professor at Brooklyn College, whose research focuses on policing.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, concentrated federal gun prosecution programs were tried across the country with mixed results. One study on Richmond, Virginia, found that it possibly sped up a decline in gun murders in the early 2000s, while another concluded it had zero impact. A 2009 study of the first iteration of Project Safe Neighborhoods, which Sessions frequently cited in public speeches, found the program only produced a 4.1 percent drop in violent crime during its existence in the early 2000s.

Despite these “small magnitude” results, Vitale argues, Sessions clung to the strategy because of a puritanical political vision, which demanded retribution against the criminal forces of lawlessness.

“I don’t think they really understand the reality of why people carry,” says Vitale, referring to supporters of Sessions’s tough-on-crime approach. “They’re so committed to the Manichean worldview and deterrence-based understanding of human nature that the only way they can respond to the failure of their programs is to double down on them.”

A political strategy honed for decades

Sessions got his first taste for harsh federal sentences against gun holders in the early 1990s as a federal prosecutor under President George H.W. Bush. Bush had won his election, in part, by tarring his opponent Michael Dukakis with the racist Willie Horton ad campaign, suggesting to voters that Dukakis was too lenient on Black criminals. With violent crime rates at an all time high, his administration’s federal prosecutors began prioritizing day-to-day drug and gun cases, shifting away from former focuses like civil rights and white collar crime. Following Bush’s call to “take back the streets” from “vicious thugs,” Sessions ramped up gun cases, as The Trace documented, often hitting people simply caught for illegal guns or drug activity.

Since the 1960s, federal administrations have consistently flaunted tough-on-crime initiatives to appeal to the fears and desires of white voters, notes Vitale. Sessions encouraged his allies to exploit the political value of such gestures for decades.

In a 1982 memo to Reagan’s attorney general, for example, Sessions pushed the White House to take on draconian anti-crime bills as a trap for its liberal opponents. “After they have come forth and identified themselves as sympathizers for drug smugglers and other assorted criminals, congregating about the bait, they should then be flattened by the President in a full-scale campaign on behalf of the legislation,” he wrote. “We support stability and order; they wander about wringing their hands crying for the criminals while violence everywhere escalates.”

I pray everyday. Leave it up to God.

Adarius Sims Birmingham resident

As attorney general, Sessions used similarly charged language when discussing violent crime and gun violence, frequently pitting “the law abiding people of this country” against the “violent thugs” and “poison peddlers.” Since the program’s launch, U.S. attorney’s offices across the country have held press conferences, announcing large-scale arrests and getting photos of guns and mugshots of Black defendants published in local news outlets.

The political dangers, on the other hand, seem to be minimal. Both gun rights and gun control advocates have publicly praised Sessions’s federal gun prosecutions. The National Rifle Association says it’s the best way to deter gun crime. The nonprofit Brady Campaign argues that prosecutors should hit illegal gun purchasers, in addition to other targets, like gun suppliers.

This bipartisan consensus on guns, however, has hurt people like Adarius Sims. Sims says he tries not to think about the charges, and keeps up his normal routine without telling many people about what’s happening.

“I’ve been working, doing what I have to do,” he says. “I really don’t think about it. I pray everyday. Leave it up to God.”

Though the average punishment for his charge is about five years, Sims and his girlfriend, who doesn’t have a job, are hoping the judge will be lenient. “Hopefully they see my background and they keep me on probation, I’m hoping.”

Though he faces sentencing in just a few months, he hasn’t talked to his kids about it. “They really won’t understand, they’re so young,” he says.

Sims insists he should not be considered one of the “leading violent offenders” that federal prosecutors claim to be targeting. Asked why he is now facing 10 years, Sims says, “I don’t know, I really don’t know… I’m not a ‘trigger puller’ or violent. I was just in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

This story was co-published with Slate.