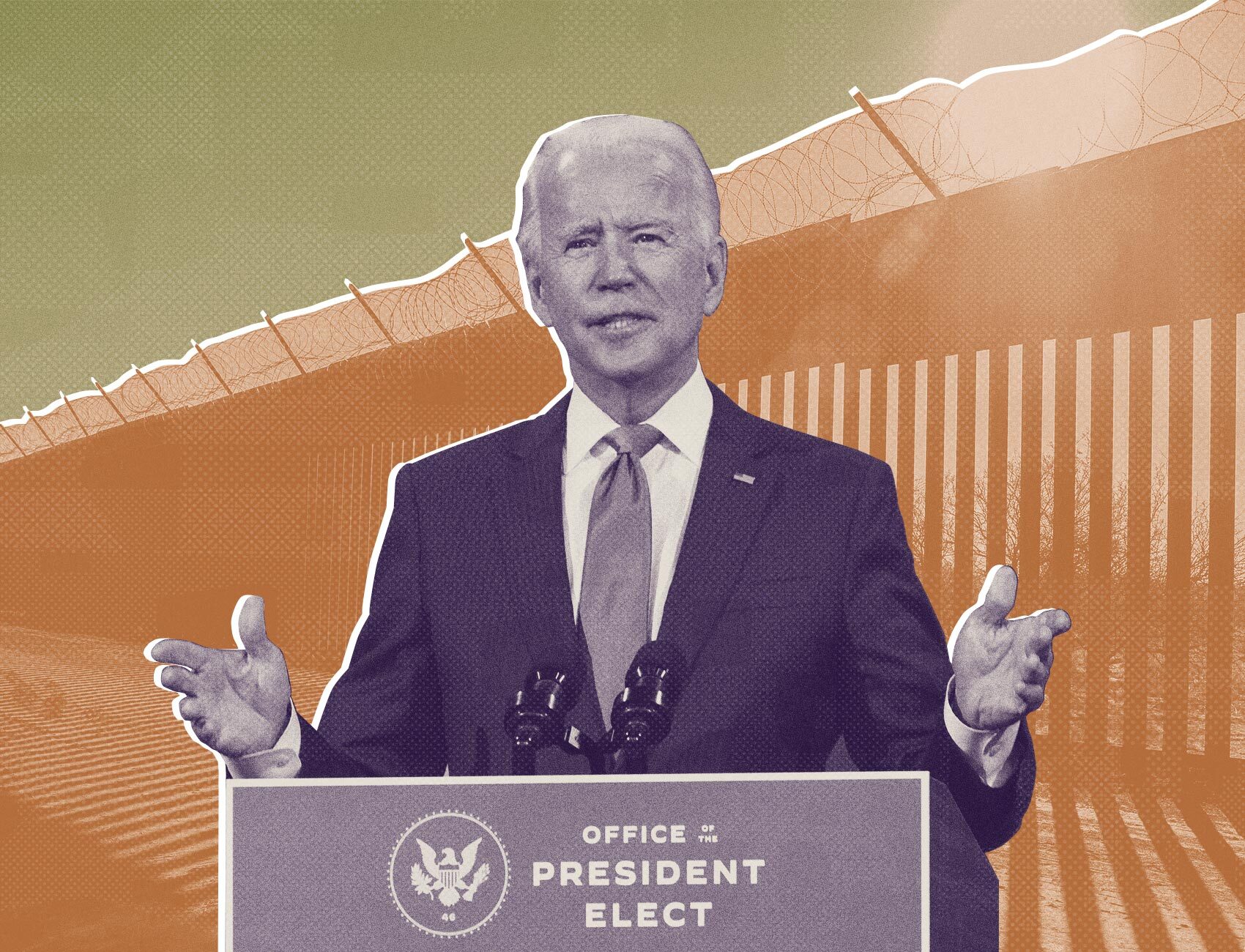

Biden’s Attorney General Needs to Think Like an Immigrant Rights Activist

With aggressive legal maneuvering, the incoming head of the Justice Department can reverse some of Trump’s most lasting harm and take steps toward a more humane immigration system.

This commentary is part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

President-elect Joe Biden has promised that he will “end the Trump Administration’s draconian [immigration] policies … and restore America’s moral leadership.”

It’s hard not to be skeptical about that, given Biden’s propensity for masking tepid platforms in ambitious language. And Biden’s promise ignores that the United States’s immigration system was a human rights disaster before Trump (Biden’s former boss holds the title of “deporter-in-chief”), and that the damage that nativist zealots have since done to that system is not easily reversible.

But if Biden is actually serious about injecting some morality into the U.S. immigration system, his administration must be bold. Like the xenophobia czars of the Trump White House, the incoming administration must be willing to buck policy-making norms—something Biden’s lane of Democrats are often reticent to do—which means taking the fight for immigration justice to new venues.

Given the unlikeliness that Democrats in Congress will be able to substantively change immigration law anytime soon, much advocacy energy has been focused on what Biden can do to tighten the leash of the U.S. deportation machine’s attack dog agencies, like ICE, under the Department of Homeland Security. But to get at the heart of some of the cruelest policies and practices, the administration will also have to weaponize the often overlooked but immensely consequential legal arm of the immigration system, via the Department of Justice and its head, Biden’s yet to be named attorney general.

With an activist attorney general, the Biden administration could sidestep congressional hurdles and rewire the immigration system in fundamental ways. Rather than simply holding ICE back from enforcing mass detention and deportation, the Justice Department could give tens of thousands of immigrants a chance to escape its clutches.

Instead of being part of the judicial branch like all other federal courts in the United States, the immigration legal system falls under the executive branch—specifically, the Department of Justice. And as head of the Justice Department, the attorney general has tremendous power over immigration courts.

Perhaps most consequentially, the attorney general can, unilaterally and at will, snatch cases from the appellate level of the immigration court system and issue their own decisions on them, in the process setting wide-reaching legal precedent. Use of this selective precedent-setting power increased under George W. Bush during the conception of immigration enforcement as homeland security. But until Trump’s election, attorneys general mostly took up cases in order to address what they saw as pressing bureaucratic issues or immigration judges’ honest misinterpretations of immigration law.

Trump’s attorneys general—first Jeff Sessions, then Matthew Whitaker (acting), and now William Barr—have taken this power to a new level. In four years, they’ve commandeered more cases than any administration since the inception of the modern U.S. immigration system, cherry picking issues to inflict what will likely be lasting damage to the application of immigration law.

Many of the cases Trump’s attorneys general targeted have centered on asylum and other persecution-based protections against deportation. In two decisions, for example, Sessions and Barr unilaterally classified certain types of migrants as being ineligible for asylum. Though federal courts intervened to overturn much of the more wide-reaching of those decisions, it still had the temporary effect of blocking almost all migrants fleeing gang violence and unchecked domestic violence—two of the biggest reasons refugees arrive at the U.S. southern border—from winning asylum. Another Barr decision made it virtually impossible for certain victims of designated terror groups to gain asylum—like former child soldiers and people forced to work for such groups under threat of death. And in yet another pair of cases, Barr severely restricted who can claim protection under the international Convention Against Torture, which is one of the most common ways immigrants who become ineligible for asylum avoid deportation to countries where they’ll be persecuted.

In addition to limiting asylum and other protections against deportation, Trump’s attorneys general have used their precedent-setting power to expand the categories of immigrants who are eligible for deportation in the first place. In one case, Barr declared that immigrants with two or more convictions for driving under the influence over a 10-year period are ineligible for “cancelation of removal”—a provision that allows for some who have lived in the U.S. for an extended period to have their deportation proceedings terminated—because DUIs indicate that they don’t pass immigration law’s “good moral character” standard. In another case, he expanded the number of criminal convictions that could trigger deportation proceedings. And in yet another case, Barr effectively blocked the practice of state criminal courts shielding people from deportation by modifying their sentences.

When Sessions headed the Justice Department, he also set several precedents that limited judges’ ability to manage their chaotic dockets by removing delayed or stalled cases. In addition to other Trump administration policies, like the euphemistically named Migrant Protection Protocols (otherwise known as the “remain in Mexico” policy), these Sessions decisions have contributed to a skyrocketing immigration court backlog under Trump—from 516,000 cases nationwide in September 2016 to more than 1.2 million last year and this year, according to data from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University. Larger court backlogs mean longer case wait times, and, for many immigrants, more time spent in immigration detention or in unsafe camps on the Mexican side of the southern border.

Though immense, the attorney general’s power over the immigration court system isn’t completely unchecked; the office’s precedent-setting decisions can be challenged in federal courts. In fact, advocates successfully sued to overturn key aspects of two of Trump’s attorneys general’s highest-profile and potentially most harmful decisions. In one, Sessions declared that, “generally,” claims “pertaining to domestic violence or gang violence … will not qualify for asylum”—a guidance that would have eliminated protections for a huge proportion of Central American and other migrants if the courts hadn’t stepped in. And in another, Barr barred immigration judges from holding bond hearings for asylum seekers who fled to the U.S., in effect subjecting them to mandatory detention for the duration of their months- or years-long immigration court proceedings.

Yet despite such oversight, the attorney general still holds wide-ranging and rarely checked power over the interpretation and application of immigration law in the United States. And Biden’s Justice Department needs to wield that power.

When it comes to the Biden Justice Department’s immigration policy, it’s clear that the central mandate is to reverse the harm of Sessions’s and Barr’s cherry-picked precedent-setting decisions. The incoming attorney general needs to take up their own cases and reorient interpretation of immigration law in ways that will yield more positive asylum cases, restrict the parameters for deportation proceedings, facilitate more releases from detention, reduce the immigration court backlog, and more.

Biden could also reverse the staffing choices of the Trump Justice Department, which promoted judges with questionable records and some of the highest rates of asylum denial to the appellate level of the immigration court system.

But Biden’s attorney general should go further than merely reversing the worst of the Trump administration’s immigration legal work. They should also seek to remedy some of the deficiencies built into the immigration legal system that have for years enabled coldhearted deportations and asylum denials.

As Sessions’s and Barr’s casework makes clear, immigration law is full of vague, malleable phrases and concepts, the definitions of which are only laid out in ever-evolving legal precedent. “Material support,” “good moral character”—a Biden attorney general could work within the vast confines of these terms to build a more humane immigration system.

Specifically, a Biden attorney general should work to redefine one of the most important phrases in asylum law: “particular social group.” U.S. law, based on international refugee law, stipulates that, in order for the government to grant a migrant asylum, the dangers from which they fled their home country must fit into one of five categories: persecution based on “race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.” But this presents a big problem: These categories date back to the aftermath of World War II, and don’t take into account the sorts of reasons people become refugees in the 21st century—like targeted gang violence, or domestic violence with near full impunity for abusers, both of which, in many places, are just as deadly and just as inescapable as race-, religion-, nationality-, or politics-based persecution.

As a result, modern asylum seekers and the lawyers who represent them are forced to seize upon the vaguest of the five acceptable causes of persecution—“membership in a particular social group”—and attempt to explain why the violence they fled fits into the definition of such an amorphous term. This dynamic is under constant debate, and has led to reams of legal opinions and precedent setting forth its parameters.

Trump’s attorneys general have taken advantage of this legal chaos. In 2018, Sessions, obsessed with curbing the flow of Central American asylum seekers, asserted that the two most common types of threats those migrants flee (gang and domestic violence) are incompatible with “membership in a particular social group,” contradicting years of case law. A year later, Barr did the same with another common “particular social group” class: those endangered because of their proximity to a family member targeted by gang violence.

It should be a priority of any legislative immigration initiative to expand the parameters of asylum beyond these outdated categories—not least because the U.S. has had a direct hand in creating the conditions that made uncategorized types of persecution so rampant in certain countries. But until that happens, the immigration court system has to work with these limits, and a Biden attorney general should do everything they can to make the interpretation of existing laws as hospitable and humane as possible.

Chris Gelardi is a New York City-based journalist.