‘She Just Said She Wanted To Be Believed’

More than 20 women accused Harry Morel, a longtime district attorney in Louisiana, of sexual misconduct. But Morel pleaded guilty to just a single obstruction of justice count while Mike Zummer, the FBI agent who investigated him, was fired. Now, Zummer is speaking about what he says is a grave injustice—at the hands of the Justice Department.

Over the years, Carla had heard rumors that Harry Morel would make problems go away for women willing to perform “favors” for him. But she never believed the awful things she’d heard about Morel, who at the time was the district attorney of St. Charles Parish in Louisiana. Morel’s wife taught at her school; he also attended church with Carla’s family.

But one day in the late 1980s Morel took Carla to lunch in New Orleans—about a 30-minute drive from St. Charles Parish—and she couldn’t shake a bad feeling in her gut.

“I know girls that I grew up with, you know, if their boyfriends got in trouble, they had to do him a favor, I had heard all this,” she told The Appeal. “I didn’t believe it because he went to church! Until it happened to me.”

Morel was a big man, both in size and in political clout. He’d been the district attorney in St. Charles, a suburban parish of about 50,000 people, since 1979. (In Louisiana, counties are called “parishes.”) District attorneys are the most powerful players in the criminal legal system, and they have an even more outsize role in Louisiana because it is the mass incarceration capital of the United States. In smaller parishes like St. Charles, DAs maintain a kinglike status.

Carla’s connections to Morel also extended to the courthouse. Just before Morel took her to New Orleans, his office had helped Carla force her ex-husband to pay child support. That day, Carla’s mother dropped her off at Morel’s office to take photos for the local newspaper. Morel kept saying that he wanted to go out to celebrate. Morel said that he’d give her a ride back to her parents’ house, where she’d been staying since she left her husband, so she relented and got in the car with him.

After Morel turned east onto U.S. Route 90, she says she asked where they were going. He said New Orleans. While driving, she says he began complimenting her hair. She’d tied it up in a bun that day.

She recalls Morel telling her that her hair “looks good up, but it would probably look even better down.” When they made it to the restaurant in New Orleans, she says Morel continued to talk about her looks.

“He kept making comments—comments that I couldn’t believe a friend of my parents would make,” Carla said.

When they finished, Carla got back in the car with Morel, even though she’d said she could hitch a ride home with her friend, who worked at a nearby restaurant. As she cracked Morel’s car door open, he reached over and pulled it shut. Carla says he then grabbed her head and shoved it toward his crotch. She stiffened.

“What are you doing?” she gasped.

“You owe me,” Carla says Morel told her, his hand still on her head. “He kept saying, ‘I’ve done [you] all these favors,’” Carla recalled. “Like, ‘I got you all this money.’”

“I know your wife!” she says she shouted. She kept pushing back against his hand. “This is insane!” she recalls saying to Morel.

In a letter Carla later sent to a federal judge, she stated that Morel “sexually assaulted” her in the car that day. Carla told The Appeal he threatened her and told her never to speak about what happened. She said she then called a friend to help take her home. When she got there, she said she walked into the house and stared at her mother.

“Don’t you ever put me in that situation again!” she barked at her mom in what she said was a fit of misplaced anger at her parents for leaving her alone with Morel. But she was too embarrassed to explain what really had happened. So she lashed out. “Promise me!”

Carla spoke to The Appeal on the condition that her real name not be used. The Appeal allowed her to remain anonymous because she says she is a sexual assault victim and is identified only by a number in FBI documents in the Morel case.

Carla says she resolved to keep the secret of what happened that day. She stopped going to church so she could avoid Morel. She eventually moved away and bought a house in another state. She underwent therapy to learn to live with what she says Morel did to her. And she didn’t speak about the incident again—until the FBI showed up at her workplace decades later and told her she wasn’t the only person Morel had abused.

In all, the FBI identified 22 women who alleged that Morel touched them inappropriately, made sexually suggestive comments, or pressured them into performing sex acts while he was the St. Charles Parish DA. Of the 22, FBI records stated that 13 said they’d had some form of sexual contact with Morel. In FBI documents—transcripts, video, audio of covertly recorded conversations, as well as an 87-slide joint FBI and St. Charles Parish sheriff’s office PowerPoint summary of the case featuring nearly two dozen witness accounts, including Carla’s, that was released to the public by the St. Charles Parish Sheriff’s Office in 2016—federal investigators laid out their claims that Morel used his office for decades to target women with offers to help them out or make criminal cases disappear if they performed sex acts for him. Five women told the FBI they’d had oral sexual contact with Morel. Eight women stated they’d had other forms of sexual contact with Morel, and nine said that he had solicited sex from them. Carla, too, cooperated with the FBI and filed a written statement during Morel’s sentencing in federal court accusing Morel of sexually assaulting her.

Another woman, Danelle Keim, helped the FBI conduct a sting and catch Morel groping her on camera—but she died from a drug overdose less than 24 hours after news of her involvement in the case hit local newspapers.

But federal prosecutors never charged Morel with a sex-related crime. As part of his 2016 plea agreement, however, Morel signed a factual basis admitting that “on other occasions, between 2007 to 2009, [he] solicited sex from other individuals who were defendants or who had family members who were defendants in the St. Charles Parish criminal justice system. While soliciting sex from these individuals, Morel likewise used the office of the District Attorney to provide benefits to these other individuals, including falsifying community service reports.”

In the factual basis, Morel admitted to harassing Keim—identified only as “Individual ‘A’”—and attempting “to prevent and dissuade Individual ‘A’ from attending or testifying in an official proceeding, i.e., the federal grand jury, by telling Individual ‘A’ to ‘get rid of’ and to ‘destroy’ the evidence of a meeting they had and to deny the inappropriate nature of the meeting to law enforcement officials.”

The factual basis signed by Morel also states that, had “this case proceeded to trial, the Government would have presented credible testimony, documents, cellular phone records, cell site information, recorded conversations, video recordings, and other reliable evidence to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Harry J. Morel Jr. obstructed justice, in violation of federal law.”

Morel was ultimately sentenced to three years in prison after pleading guilty to a single obstruction of justice charge in federal court in New Orleans. (He was also forced to pay a $20,000 fine and serve one year of supervised release.)

Morel served a little less than two years of his sentence—and he spent a portion of that time in a halfway house in New Orleans. He was released on Aug. 6, 2018. Morel’s legal team did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story. In previous statements to the press, Morel attorney Ralph Capitelli has described the FBI’s claim that his client was a serial sexual predator as a “smear tactic” to influence the court during sentencing that was “both unfair and, in my judgement, impermissible.” Capitelli has also said that Morel “denied and still denies any type of sexual assault on any woman whatsoever.”

Some of the key people involved in the Morel case—the lead FBI agent who investigated him, the St. Charles Parish Sheriff, and multiple alleged victims—say it was a miscarriage of justice brought about by a flawed prosecution that treated a powerful man with kid gloves despite evidence suggesting he’d abused his elected position for decades.

Peter G. Strasser, the current U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Louisiana, told The Appeal he could not comment on the case since he was not appointed to the position until 2018. The Appeal contacted every assistant U.S. attorney referenced in this story and did not receive a response; Strasser declined to comment on their behalf and stated that assistant U.S. attorneys are barred from speaking to the media. Though the FBI agent leading the investigation filed multiple complaints against federal prosecutors in relation to the case, internal department investigators have repeatedly cleared U.S. attorney’s office employees of wrongdoing.

Aya Gruber, a professor at the University of Colorado-Boulder Law School and former federal public defender, said the criminal legal system generally fails to prevent sexual and domestic violence, and prosecutors tend to focus on men from marginalized communities while balking at taking on more well-connected people.

“When I was a public defender, I saw plenty of men—and mostly marginalized men—prosecuted for sex assault for things like, say, grabbing somebody’s butt on a dance floor,” Gruber, author of “The Feminist War on Crime: The Unexpected Role of Women’s Liberation in Mass Incarceration,” told The Appeal. “The idea that the government never takes sexual assault seriously—personally I think it has a lot to do with who the people are and what their connections may be.”

One of the harshest punishments meted out in the Morel case was against one of the people who investigated him: New Orleans-based FBI Special Agent Mike Zummer, who says he was fired for complaining about a lenient plea deal for Morel and what he says was one federal prosecutor’s cozy relationship with Morel’s attorney. Zummer outlined these complaints in a series of letters he sent the judge in Morel’s criminal case, Kurt Engelhardt, in connection with Morel’s sentencing for obstruction. The letters later became public as part of a civil lawsuit Zummer filed against the FBI.

Zummer complained to both Judge Engelhardt and the DOJ’s inspector general that Fred Harper, a federal prosecutor in the Eastern District of Louisiana, co-owned a vacation home with Morel’s attorney, Capitelli. In Zummer’s opinion, the relationship “caused at least an appearance” of partiality at the DOJ. In a 2018 report, the inspector general found “no evidence” that the relationship between Capitelli and Harper “improperly influenced” the U.S. Attorney’s initial decision not to bring charges against Morel in 2013.

Neither Harper nor Capitelli responded to requests for comment. The 2018 report also found no misconduct by DOJ officials.

In a press conference after Morel’s guilty plea in 2016, then-U.S. Attorney Kenneth Polite told the public that his office declined to file stronger charges against Morel due to “significant evidentiary concerns,” including a fear that the testimonies of Morel’s accusers would not stand up in court. Polite did not respond to a request for comment.

After Zummer reported his complaints—including in a letter to the U.S. Senate’s Judiciary Committee chair—he was suspended from the FBI and fired earlier this year. In October, the DOJ filed a bar complaint against Zummer, who holds a law license in Louisiana, for allegedly sending the aforementioned letters to the judge in Morel’s criminal case without proper approval from the DOJ. Zummer denies any wrongdoing.

In April 2017, Keim’s mother, Tammy Glover, sued Morel and an associate of Morel’s in St. Charles Parish civil court for racketeering. The lawsuit claimed Morel extorted sexual favors from Keim and at least 21 other women in exchange for reducing or dismissing criminal charges against them. The suit was later dismissed. One of Glover’s attorneys, Glenn C. McGovern, told The Appeal that the DOJ “dropped the ball” in its Morel prosecution and called the outcome “nauseating.”

“Sometimes things don’t work out, and sometimes the system doesn’t work,” he said.

That August, Zummer sued the FBI in federal court for violating his First Amendment rights; the defendants sought to dismiss the lawsuit, arguing, among other things, that they were acting within their discretion to suspend Zummer’s security clearance, and that he violated his FBI employment contract and other FBI regulations by disclosing his letters to Engelhardt. Some of Zummer’s claims have been dismissed by the court, but his assertion that his First Amendment rights were violated by the FBI for its refusal to publish his unredacted letter to the public remains part of his ongoing lawsuit.

Zummer is represented by Robert McDuff, a veteran civil rights attorney who was the lead attorney for Curtis Flowers, a Mississippi man tried for the same murder six times before charges against him were finally dropped this year and whose case was the subject of a hit podcast. McDuff declined to comment for this story.

Zummer told The Appeal this year that the outcome of the case shattered his faith in the DOJ. “Financially, you look at what I did, you look at my record, you look at his record, you look at where I’m at, compared to where he’s at,” he said. “Yeah, I mean—it pays to be a sexual predator.”

Zummer also filed a separate complaint with the DOJ’s Office of the Inspector General, the agency’s internal watchdog, alleging he’d been retaliated against for speaking out about the case. However, the office’s June 2018 report cleared the FBI and DOJ of any wrongdoing and stated that it did not find evidence Zummer had been retaliated against.

An FBI spokesperson declined to comment on Zummer’s firing, stating that the agency does not “comment on personnel matters.”

In court pleadings filed in response to Zummer’s pending federal lawsuit, the FBI has also argued that Zummer was legally suspended from the agency and that he was fired for violating the terms of his employment as a special agent.

“About one week before his security clearance was suspended, FBI officials informed Zummer that he could no longer be assigned investigative work because Zummer had taken the position that he was free to publicly disclose information he gathered during the course of his official duties as an FBI Special Agent,” attorneys for the FBI wrote in 2018. “FBI officials believed that it was Zummer’s position that this information, which was the property of the United States, could be disclosed without first receiving authorization from the FBI even though Zummer was obligated by the terms of the FBI Employment Agreement to seek and obtain authorization prior to disclosing FBI information.”

In October 2018, the OIG issued a separate report into allegations about Zummer, which also stated that he had disobeyed orders and violated the terms of his employment when releasing his letters to Engelhardt. But that investigation found “mitigating factors” in Zummer’s favor, including that the “instruction Zummer obtained” from the DOJ’s Office of General Counsel “was faulty.”

In a previous statement to the press, Capitelli called Zummer a “disgraced rogue FBI agent who is trying to desperately salvage his career.”

Mark Osler, a former assistant United States attorney in the Eastern District of Michigan (Detroit) who now teaches law at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, reviewed aspects of the Morel case at The Appeal’s request. He said that although Zummer might not have followed proper whistleblower procedure, he “obviously has a moral compass and took a big risk in making public something that he knew would harm him professionally.”

St. Charles Parish Sheriff Greg Champagne, who worked closely with the FBI on the case, told The Appeal he believes Morel received a lenient plea deal and that Zummer was mistreated by the FBI.

“I can honestly say I have never met anyone with more honesty and integrity than Mike,” he said. Before his tenure as sheriff, Champagne was a prosecutor in Morel’s office from 1982 to 1995. He said he was unaware that Morel was allegedly engaged in sexual misconduct until the FBI began its investigation years later.

“Do I believe he deserved more? Yes I do,” Champagne said of Morel’s prison sentence. “Knowing what I know and what I believe he did? Yeah. I think he should still be in prison to be honest with you.”

Tessie Keim, sister of deceased witness Danelle Keim, told The Appeal that Zummer became like family during the investigation and believes he was treated too harshly by the FBI.

“He lost it all over it,” she said. “And so we’re just extremely grateful. He knows if there’s anything he ever needed, he could just pick up the phone, call any one of us, and we’re there.”

Multiple efforts to reach Morel were unsuccessful.

The FBI’s first chance at investigating Morel came in 2001, when according to the agency’s internal PowerPoint outlining a timeline of the investigation, an unnamed witness contacted the agency and told agents that, as part of a DWI case, Morel asked her to meet. She told the FBI she believed he wanted sexual favors. But the FBI’s New Orleans field office closed the investigation shortly afterward because of a lack of evidence.

By then, Morel had become a big name in Louisiana politics. Harry J. Morel Jr. was born in 1943. Morel received an undergraduate degree from Louisiana State University in 1965 and later took his first law job with then 29th Judicial District Court Judge Joel T. Chaisson—father of current St. Charles Parish DA Joel Chaisson II. Morel was elected DA in 1978 and won five straight elections without fielding a single opponent. He prosecuted at least two cases in which he successfully argued people should be executed; his office convinced the state to execute a man with significant intellectual disabilities in 1987. Morel also once served as president of the Louisiana District Attorneys Association, one of the most powerful lobbying groups in the state. In 2009, then-Governor Bobby Jindal also appointed Morel to serve on the Louisiana Drug Control and Violent Crime Policy Board. That same year, Morel was inducted into the Louisiana Justice Hall of Fame.

Also that year, Zummer says he was sitting in a group of cubicles at the FBI’s New Orleans field office when his boss asked if anyone would look into a tip that had just come in about Harry Morel.

I raised my hand, and that has changed my life.

Mike Zummer former FBI special agent

Zummer, 49, was born in the Chicago area and graduated with a political science degree from Duke University in 1993. He later enlisted in the Marine Corps, and did tours in the Persian Gulf and Western Pacific before taking a job with the FBI investigating white-collar crime in New Orleans. When President George W. Bush announced the invasion of Iraq in 2003, Zummer joined the Marines yet again, this time as an adviser for the Iraqi security forces and as a public-corruption investigator in Al-Anbar province. He earned a law degree from Stanford before returning to the FBI’s New Orleans field office.

This time, Zummer joined an FBI public corruption unit that, in tandem with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Louisiana, was hailed in the local media as “modern-day untouchables” after a series of successful post-Hurricane Katrina cases targeting New Orleans police and politicians. Jim Letten, the chief U.S. attorney in that office at the time, was so adept at prosecuting public corruption cases that President Barack Obama declined to dismiss him upon taking office, even though Letten had been appointed by President George W. Bush.

“I raised my hand,” Zummer said of his boss’s request. “And that has changed my life.”

Zummer’s boss at the FBI explained that the St. Charles Parish Sheriff’’s Office had received a 911 call from a woman who had asked for help taking care of a third party’s traffic ticket. According to the FBI and St. Charles Parish sheriff’s office PowerPoint summary of the case, she said she’d spoken to Morel four times, and that he suggested she travel to a house he owns in Mississippi where they could “play.” The woman asked Morel what she needed to do for the ticket. Morel backed off, but according to the FBI PowerPoint summary, he suggested they could “go do something” after the case ended. When she said she wasn’t going to have sex with him, Morel stopped calling her back. The third party with the ticket was sentenced to several years in prison.

“I basically called the FBI cold and got a referral and Zummer ended up calling me back,” Champagne, the St. Charles Parish sheriff, told the Appeal.

Zummer was eager to investigate Morel further, but the witness was uncooperative. “The natural thing for an FBI agent—and particularly in corruption—is to do something covert,” Zummer said. “You want to find somebody to wire up on him. We really had a hard time figuring out what to do.”

But Zummer’s luck changed on April 16, 2010, when Champagne’s office alerted the FBI that it had received a frantic 911 call that evening from a woman who said she was groped by Morel.

The caller sounded rattled.

“Um, yes sir, my name is Danelle McGovern,” she told a dispatcher, according to an audio recording and transcript of the 911 call, which were released publicly in 2016. (She pronounced her name “Danielle” and later returned to using her maiden name, Keim.) “I need to make a complaint. I need the cops out here.” She then gave her address—an apartment complex on East Club Drive, a tree-lined street in tiny St. Rose, Louisiana—to the dispatcher.

“And what was your name?”

“Danelle McGovern. I need to make a sexual harassment charge on Harry Morel.”

“The district attorney?” the dispatcher asked.

“The district attorney, yes,” she responded. “I have all the evidence.”

As Keim provided the dispatcher with her phone number, she began to weep.

“OK, when did this happen?”

“Just now,” she said, sniffling audibly through tears. “He just left my house 10 minutes ago.”

Keim told the dispatcher that she’d recently been arrested for a DWI in St. Charles Parish and was meeting weekly with Morel to discuss what could be done about her case. She said she’d blown a 0.00 on a breathalyzer test and asked Morel for help.

“I didn’t know he was like that, you know?” she continued. “So he was like, ‘How about I come to your house?’ I just kinda felt that it kinda sounded weird, but he’s district attorney, so what harm can he do?”

“Exactly what did he do?” the dispatcher asked.

“He grabbed me,” she responded. “He kissed me and he touched me in my private area, he touched me in my ass. He wanted me to take off my clothes. He wanted me to take my pants off so he could please me.”

The dispatcher thanked Keim and hung up. By then, the sheriff’s office was aware of Zummer’s burgeoning investigation into Morel, so it asked the FBI to meet with Keim. Zummer arrived later at Keim’s one-bedroom apartment in St. Rose. Sheriff’s deputies were already at the home and ushered Zummer inside to meet Keim, a petite then-24-year-old. Keim had recently been arrested for a DWI and was supporting herself and her young son by working at a Quiznos.

Tessie Keim, Danelle’s younger sister, told The Appeal that Danelle had “such a large personality,” loved to sing and dance, and doted on her young son. At the same time, both sisters could be intense and intimidating when the need arose.

“She just was very strong, she just had an inner strength always, since we were kids—very fearless,” she said.

Although Keim sounded distraught on her 911 call, Zummer remembered that she was calm during his first visit with her.

“From the start, she just said she wanted to be believed,” Zummer said.

Keim told the FBI that Morel first tracked her down at the Quiznos where she worked and called her on the job. Keim met Morel in his office, where she told the FBI he showed her a picture of his house in Mississippi and hugged her. According to the FBI PowerPoint, after meeting Morel a second time, Keim assumed he was going to dismiss her case. But she told Zummer that when she got a court summons, she called Morel again and asked him to meet.

“He claimed he was in the neighborhood, I think back from a golf tournament, and he told her he’d come right by,” Zummer remembered.

Keim told investigators that her son wasn’t in the apartment when Morel arrived. According to a handwritten statement Keim filed with the St. Charles Parish sheriff’s office, Keim said Morel promised to help her—and also asked for sex. Keim said she told Morel she had to go pick up her son that night. In her statement, she told investigators that she tried to walk Morel out of her apartment, but “before I could open my door, he grabbed me and started kissing me and feeling on me. I backed away and when I turned around to open my door, he grabbed my privit [sic] area in between my legs and then ran his hans [sic] all over my ass. And was touching me very firmly.”

After she told him to leave, she wrote that Morel “told me to call him anytime, and if his wife answers, to just tell her I’m just calling about my case.”

But after Zummer’s first meeting with Keim, she stopped cooperating with the FBI. Zummer didn’t hear from Keim again until July 2011, when she went to meet with Morel to ask him to help her then-boyfriend, who faced burglary charges. By then, Keim had also been arrested for a second DWI in neighboring Lafourche Parish.

“That was where he started touching her with, I think I would say her ‘forced consent,’” Zummer said.

According to the FBI’s PowerPoint case summary, Keim met with Morel at the St. Charles Parish Courthouse on July 4, 2011. She told the FBI that Morel asked her if she was taking birth control, and that he wasn’t pleased when she said she wasn’t. Morel then allegedly grabbed her breast and kissed her. Keim said she heard someone nearby, so the pair agreed to meet at a satellite office that was likely to be empty. They took separate cars; Morel drove a white Chevrolet Suburban, while Keim drove a white Pontiac Grand Prix.

Once they were at the satellite courthouse, Keim told the FBI, Morel set ground rules. She alleged she could ask about her boyfriend’s case—but for every question, Morel would get to touch her body. After the first question, she said Morel grabbed her breast. When Morel eventually promised not to let her boyfriend go to prison until later, Keim said he put his hand down her pants. He wanted her to touch him, and she said she was having her period. She told the FBI he unbuttoned her pants and began breathing heavily; he said he’d be fast when they had sex. Morel asked if she wanted to go to a hotel room with him. Using her son as an excuse, she was able to escape.

Four days later, Morel asked Keim to meet him again, this time at a daiquiri shop. As Keim told the FBI, she sat next to him in his car. He told her he was doing a lot for her and that he wasn’t getting much in return. Morel said he was thinking of seeking a sentence of five to seven years in prison for Keim’s boyfriend—and then allegedly unzipped his pants and began touching himself.

Zummer was later alerted that Keim had met with Morel again. He and another agent contacted Keim and met her in a park. Zummer shared personal notes of the meeting with The Appeal; he remembers Keim as inebriated, barely able to walk, her eyes glazed over. Zummer drove Keim to a restaurant in Metairie, a city in neighboring Jefferson Parish, before taking her to a Starbucks as she sobered up. Zummer interviewed her again the next day. As she told him a story about sleeping while clutching toilet paper during a stint in jail to prevent others from stealing it, Zummer realized that this was the closest he’d gotten to someone on the opposite end of the criminal legal system.

“I knew how to put people in jail, but I didn’t know what happened to them afterwards,” he wrote.

After Keim was arrested in August 2011 for shoplifting from a Walmart, Zummer met her in jail and pushed her to cooperate with the FBI; he admitted that he threatened to charge her as a co-conspirator in the Morel investigation if she didn’t agree to do so, a decision he says he now regrets. Keim agreed to work with the FBI to put together a sexual bribery case against Morel, which required recording him explicitly agreeing to extort sex for legal favors.

The FBI then helped get Keim into a drug treatment program. Later, Keim told Zummer that she was bouncing between homes—so the agency helped move her into a new apartment with spare furniture from its New Orleans field office. Keim then agreed to start wearing a wire and record conversations with Morel. (Tessie Keim said she remembers helping fix Danelle’s wire to keep it hidden under her bra at one point.)

Several months after Keim began cooperating with the FBI, Morel stepped down from DA to a top assistant job because his daughter, Michele Morel, had decided to run for a judgeship in Louisiana’s 29th Judicial District. (He fully retired from the office in January 2013.)

In June 2012 , Keim entered a guilty plea in her DWI case in Lafourche Parish and was sentenced to 64 hours of community service. On July 17, Morel was recorded promising to help Keim fake that she’d been volunteering at a Lions Club outpost in St. Charles Parish as part of her community service requirements.

“So what do I have to do at this Lion’s Club?” Keim asked, according to a transcript included in the factual basis Morel signed as part of his plea deal.

“You have to do what?” Morel responded.

“Like, what do I have to do?”

“The Lion’s Club? Nothing.”

While on tape, FBI records state Morel then suggested meeting her for a drink. He again floated the idea of meeting her at his Mississippi ranch and joked that it would be fun to give her “mouth-to-mouth.”

Morel and Keim spoke again by phone three days later. According to FBI audio tapes of phone calls between them on July 20, 2012, Morel updated Keim on the status of her fake community service records before she mentioned that her son was out of the house that week. They soon hung up. But, per the FBI’s PowerPoint case summary, Morel called back shortly after and started suggesting the pair meet at her house. She was able to put him off a few days.

“Oh, God,” Keim breathed into a microphone hidden underneath her clothes. “He’s here.”

On July 23, 2012, Morel arrived at Keim’s new apartment wearing light-blue jeans and a tan polo shirt. He brought root beer and wine, sat down on a dark-colored couch in front of a coffee table and small potted plant, and started to make small talk. Zummer listened to the conversation from a secure location nearby. The FBI also set up a hidden video camera directly in front of the couch.

“When he pulled in, she kind of started crying a little bit from the tension,” Zummer said. “What was just so amazing about her is that you could hear it in her voice—that ‘oh, God,’ that very genuine fear. But as soon as he showed up, she was on. She swallowed her fear down and suppressed it and she was just on top of it.”

According to a transcript of the conversation obtained by The Appeal, Keim said she didn’t know how to uncork a bottle of wine, so Morel showed her. Eventually, she asked Morel if he minded her smoking a cigarette. He told her not to, because he was going to kiss her and wind up smelling like smoke. He asked about her new apartment, her new job at a local bar, her new car.

In a video of the sting, Morel asked Keim to kiss him—she relented and said she would give him a “peck.” Morel then pulled her body closer to his while he ran his hand down her buttocks. Morel also excitedly asked if he was “an important guy” and, if so, could order her to kiss him.

“I got a deal for you, though,” she said. “Let’s see if we can make a deal.”

“What is it?”

“What’s the furthest—we, we never really went, really, we never really went further than kissing and just kinda touching and feeling,” she said. “What do you want from me?”

What was just so amazing about her is that you could hear it in her voice—that ‘oh, God,’ that very genuine fear.

Zummer former FBI special agent

Everything hinged on that question. Morel was a longtime prosecutor, and investigators knew it would be hard to get him to incriminate himself.

“I don’t know,” he said, seemingly ducking the question. “I want to spend some time with you.”

“You say that but you never—and I know you’re busy—but you never—”

“Well, I think about making love to you but then, you know, it gets me nervous, too,” he said. “And I don’t—but that’s not why I’m helping you. So I just sort of back off.”

She told him she was nervous about making enough community service hours in her case—and suggested that she might be able to let Morel touch her if he was able to help falsify records showing she’d been keeping up with her hours. She pleaded with him not to let her go to jail.

Keim then made it clear she wouldn’t sleep with Morel until he gave her the new, faked records showing she’d been complying with her community service requirements.

“I’m just saying just let me see, once all this is done, let me see the papers so I’ll know that I’m OK,” she said.

“Whatever you want,” Morel said.

Shortly after, Keim asked Morel to visit her at work.

“I gotta stay away until I got the papers,” he joked.

With that, Zummer thought he’d nailed the district attorney.

On Nov. 29, 2012, Keim alerted Morel that they had been followed and photographed, according to the FBI’s PowerPoint case summary.

One photograph showed a red-brick building with white colonial columns and shutters around each door. A white Chevrolet Suburban sat one space away from a Pontiac Grand Prix. In front of the cars, a sign on the lot read “Harry J. Morel, Jr., District Attorney.”

Keim’s boyfriend had tailed their cars on July 4, 2011—the day Morel pressured Keim to have sex with him in a satellite office. And on Nov. 29, 2012, the boyfriend was asking Keim to send the pictures to the FBI. That day, Morel, in a blue gingham shirt, sat down with Keim at a table in his office.

“You know, I don’t like hearing all this,” he said, according to FBI recordings. “We gotta get rid of that and put this all behind us. You can’t talk to that guy.”

“I know,” Keim said. “That’s why I come to you. I’m not gonna fucking talk to him. I’m not answering my phone, I’m changing my fucking number, something. Or I can block it. I can block his number.”

The incident was a set-up, and Keim was nailing her acting role. The photos were real—she had asked her then-boyfriend to tail their cars and photograph them before she’d even begun cooperating with the FBI—but Keim and her boyfriend had already turned the images over to the FBI. And Keim was recording the November 2012 conversation with Morel.

Keim played Morel perfectly. Morel had recently coordinated sending two faked letters to the Lafourche Parish district attorney’s office, according to the factual basis later signed by Morel. John J. Landry III, who ran the Luling-Boutte Lions Club in St. Charles Parish, wrote that Keim volunteered for 64 total hours between July and September 2012 at the club. Landry falsely told prosecutors that Keim had helped out at bingo, swept, organized nursing home supplies, and even delivered meals to needy people.

Sitting with Keim that day in November 2012, Morel directed her to destroy the memory card containing photos of their two cars parked next to one another.

The FBI gave Keim a copy of the card and sent her the next morning to hand over the evidence.

“How are you going to destroy it?” she asked. “It’s hard. You can’t even—I can’t even break it. I tried to crack it.

“Throw it in the garbage,” Morel responded.

“The garbage?”

“Yeah,” he said.

“Aren’t you going to break it or something, cut it up?”

“Well yeah, I can do that,” he said. He added that he was going to “get a hammer.”

In early 2013, the FBI’s investigation into Morel became public, and a federal grand jury issued a subpoena demanding that Morel turn over the memory card. Morel, meanwhile, had hired his own legal team, led by veteran defense attorney Ralph Capitelli. Capitelli is well-connected in New Orleans; he unsuccessfully ran for Orleans Parish district attorney in 2008 and this year was named the 63rd president of the organization that runs the Sugar Bowl college football game at the Superdome.

On Jan. 11, 2013, two major events in the case occurred. First, FBI agents arrived at the St. Charles Parish district attorney’s office and asked for consent to search the building.

Joel Chaisson II, who replaced Morel as St. Charles Parish DA, allowed the FBI to hunt through Morel’s office. According to the FBI’s investigative notes, an agent opened one of Morel’s desk drawers and found the torn open packaging for a memory card reader. Morel’s attorneys told the FBI that the memory card was in the office, but there was no card to be found.

That same day, the FBI paid Landry a visit. FBI agents showed Landry the faked papers that said Keim had worked there and asked whether he’d supervised her.

“Yeah, mostly,” Landry said. The FBI then asked him to pick Keim’s face out of a lineup of photos. He wasn’t able to do so. He then claimed it was “too early in the morning” to recognize her.

Five days later, Landry confessed. He admitted to the FBI that he’d faked Keim’s paperwork and other letters for Morel. He admitted to having falsified a letter for a local priest on Morel’s behalf. In exchange, he told the agency that Morel helped take care of traffic tickets for Landry’s acquaintances. The St. Charles Parish DA’s office later charged Landry with four counts of filing false records and four counts of conspiring to file false records. Although Chaisson’s office recused itself from the Morel investigation, it did not do so in Landry’s case. Chaisson’s office offered Landry a pretrial diversion agreement in which he agreed to complete 129 hours of community service and pay $2,500 in fines and fees in exchange for dropping the charges.

Keim was adamant that she didn’t want to take on Morel by herself. So Zummer and his partner continued their search for other women. Word was getting around the St. Charles Parish sheriff’s office that the FBI was on the hunt for tips about Morel. Sheriff Champagne told The Appeal that a friend told him his daughter—Carla—once came home upset after Morel took her to lunch in New Orleans.

“I think word got out that you could trust the sheriff’s office to pass on valid information,” Champagne said. “So we got a few more leads. One big one in particular was a friend of mine who came forward and told me about his daughter.”

Champagne says he passed the tip on to the FBI.

“Next thing I knew,” Carla told The Appeal, “there’s somebody at the front counter” of her workplace.

“It was an FBI agent,” she said. “I looked at him with a cold stare and said, ‘I’m not talking, you can’t make me, nothing’s ever going to come out of this.’” But, eventually, she agreed to cooperate as a witness.

The FBI’s investigation was also starting to attract significant media attention. Around the beginning of February 2013, Zummer said someone leaked Keim’s name to a reporter at the New Orleans Times-Picayune, the city’s newspaper of record. The reporter asked Keim to speak to him.

Keim called Zummer about the reporter. “I was out of town by this point, driving on the side of the road in Texas,” Zummer said. “We’re having an argument about it. I think I told her I’d never talk to her again if she’d talked to the press. And that really hurt her. I had become a big source of support for her.”

Keim mentioned that her boyfriend wanted to get engaged, but she wasn’t as enthused about it. She also fought with her boyfriend and some of his acquaintances and asked Zummer “to come help get rid of them, or whatever.” He told her to call the sheriff’s office.

Zummer said he stayed on the phone with Keim the night of Feb. 8 for hours. He estimates they talked on and off from the time he left Dallas until he hit Alexandria, Louisiana, on I-49 at about 5:15 p.m. She’d asked Zummer to stop by her home, but he said he wasn’t feeling well and that he was still hours from New Orleans.

“I was stuck in traffic about west of Baton Rouge on I-10, and I got some gas, and saw that it had hit the Times-Picayune and NOLA.com,” he said. “It didn’t name Danelle, but this ex-boyfriend was identified, and Morel would know who she was.”

Zummer said the drive home from Texas wore him out. He felt sick and fell asleep without remembering to plug his phone into its charger. He spent the morning of Feb. 9 watching “Law & Order” and trying to ignore a sore throat. But when his phone was finally charged, he saw that he had three voicemails, including one from the St. Charles Parish sheriff’s office. Sensing danger, he called the sheriff directly.

“Danelle’s dead, Mike,” the sheriff said. “I’m sorry.”

Zummer says he crawled into the shower and started weeping. Then, hands shaking, he put on a suit and drove to the crime scene. News reports later stated Keim’s new boyfriend, a 28-year-old named Matthew Savoie, called 911 in the early morning hours of Feb. 9 to report a drug overdose. In an arrest warrant application filed later that year, police said they arrived to find Savoie attempting CPR on Keim at 5:25 a.m. surrounded by puddles of water pooling around both floors of the house. Emergency medical professionals were unable to revive her.

According to Savoie’s arrest warrant, he said he met a friend in a Circle K parking lot on Feb. 8 who offered to distribute “mollies.” A different witness told detectives she later drove to Savoie’s residence and sold him five pills for $80. Savoie and Keim each took one at around 10 p.m., and then a second pill later that night. He says he fell asleep. In one interview, Savoie stated that he woke up in his bedroom and was alarmed when Keim wasn’t there. In another, he said he awoke around 4:30 a.m. in the kitchen, went to look for Keim, and found her lying facedown on the living room sofa. Savoie said he poured water on her and carried her upstairs, attempted to place her in the tub, and tried to wake her up by running the shower on her body. When that didn’t work, Savoie called 911.

The arrest warrant states that Keim ingested an “extremely high” dose of methylone, or MDMC—a cathinone analogue that drug dealers substitute for the more sought after MDMA, or Ecstasy.

The sheriff’s office ultimately arrested six people in relation to Keim’s death. Savoie was initially charged with the distribution, manufacture, or posession with intent to distribute a Schedule I controlled dangerous substance, as well as second-degree murder—a charge that carries a life without parole sentence in Louisiana. In November 2013, Savoie pleaded guilty to a lesser count of felony distribution of a Schedule I narcotic and was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Zummer noted that in addition to the stress of the investigation, Keim had been dealing with a series of family and relationship issues. Zummer believes Keim and her boyfriend each took the same dose of MDMC, but because she was simply much smaller than Savoie, she overdosed.

On Feb. 22, 2013, Zummer, two FBI agents, and a victim specialist attended Keim’s funeral. By then, news had broken that Keim had been cooperating with the FBI. Zummer wanted to place an FBI lapel pin on Keim’s body. Even though his bosses disagreed, he handed the pins to Keim’s family, who placed them under her blouse during the viewing.

As Zummer met members of her family, he told them how much he admired her. “I did a tour in Iraq with the Marines,” he said, “and she’s as brave as anyone I’ve ever known.”

Tessie Keim said the experience was “kind of like an out-of-body experience for all of us.” She added that she now works with local women’s shelters to help carry on her sister’s legacy, as she believes Danelle would have helped other women deal with their trauma once the Morel case ended. “She wouldn’t be cowering from it, she wouldn’t be sad about it, she wouldn’t have been any of those things,” Tessie said. “She would have been joyous. So we just really are trying to live that way about the situation for her.”

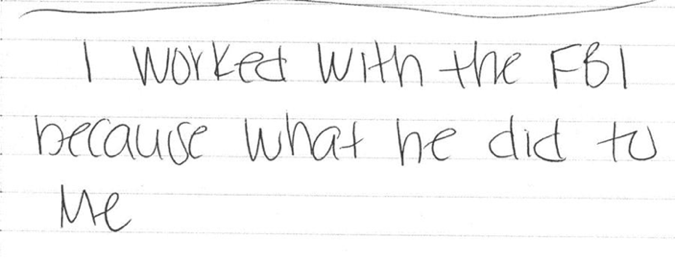

When searching Keim’s home after she died, sheriff’s deputies found that she’d been keeping a diary. Zummer remembers another agent bringing the diary to him and showing him a page.

“I worked with the FBI because [of] what he did to me,” it read.

After Keim’s death, it seemed like the case against Morel was falling apart.

The U.S. attorney’s office in New Orleans was also in freefall. In 2011, a defense attorney for one of the office’s targets determined that a commenter on the Times-Picayune’s website was a veteran prosecutor who’d been disparaging criminal defendants, judges, and other people involved in the legal system. Another prosecutor later admitted that she, too, had been commenting anonymously on NOLA.com.

The online commenting scandal led to fallout for both the U.S. attorney’s office and at least one of its major cases. In December 2012, U.S. attorney Letten resigned; in September 2013, verdicts in the Danziger Bridge case—a police killing after Hurricane Katrina that left two dead and four others wounded—were overturned by Engelhardt, who blasted “grotesque prosecutorial misconduct” in his written opinion. (Later, five Danziger officers entered guilty pleas to charges that significantly reduced their sentences.)

“Everything was really set back,” Champagne told The Appeal.

Toward the end of 2012, veteran federal prosecutor Dana Boente—who briefly served as acting U.S. attorney general in 2017 after President Trump fired Sally Yates—was flown in from Virginia to temporarily oversee the office. Boente did not respond to a request for comment from The Appeal.

With their lead witness deceased, Zummer says he was under pressure. He says one prosecutor on the case pushed him to come up with new evidence within a few weeks’ time. Over the ensuing weeks, Zummer broke sharply with federal prosecutors over their assessment of the strength of the Morel case.

While Keim was alive, Zummer said prosecutors complained that she wasn’t a strong witness. After she died, prosecutors said the case couldn’t go on without her. According to a 2018 Office of the Inspector General report, which was recently made public as part of Zummer’s lawsuit against the FBI, Zummer said that on Feb. 15, 2013, a prosecutor—unnamed in the report—told him that “after [the witness’s death] the case against Morel, which was difficult before, has since become impossible.” According to Zummer, that same prosecutor also argued that Keim’s tapes would no longer be admissible in court. Zummer told The Appeal that he disagreed with the prosecutor on the admissibility issue. (On March 7, 2013—almost exactly a month after Keim’s death—Morel’s attorneys found the missing memory card and gave it to the FBI, according to the FBI’s PowerPoint summary of the case.)

On April 9, 2013, the U.S attorney’s office formally declined to file charges against Morel, according to the FBI’s PowerPoint. Zummer fumed. He hadn’t had time to find new witnesses.

“I did not understand why the case had been declined,” Zummer later wrote to Engelhardt. “I had not asked that it be prosecuted. I wanted to obtain records to identify potential victims for interviews. At the time, we were aware of three women, including Keim, and believed there could be more victims. The sudden declination appeared to be designed to stop the overt investigation before it had the opportunity to start.”

Zummer complained to the DOJ’s Office of the Inspector General in May 2013 that a prosecutor in the Eastern District of Louisiana, Fred Harper, co-owned a vacation home in Gulf Shores, Alabama with his girlfriend, Capitelli, and Capitelli’s wife. Zummer told the inspector general’s office that Harper was involved in meetings about the case prior to the 2013 decision to decline prosecution.

But the inspector general’s office reviewed Harper’s work text messages, emails, and phone records and also interviewed Harper and other lawyers in the U.S. attorney’s office. In a June 2018 report, it “found no evidence” that Harper “had any substantive involvement in the Morel case or in the declination decision, or that [Harper’s] relationship with the Defense Attorney improperly influenced the USAO’s declination of the Morel case.”

According to the DOJ Inspector General’s Office, which also reviewed property records, Harper had begun divesting himself of the condominium in November 2012 and fully ceded legal ownership of the property to his girlfriend in March 2013—one month before the U.S. attorney’s office made the decision not to pursue charges against Morel, and more than one month before Zummer complained about it. Alabama property records confirm that Harper has fully deeded his share of that home to his girlfriend.

Zummer demanded a meeting about the decision not to bring charges. On April 17, 2013, eight days after prosecutors made that decision, Zummer joined Boente, Harper, and several employees from the FBI and the U.S. attorney’s office to discuss the case.

According to Zummer, prosecutors sharply criticized the evidence against Morel. As Zummer told the inspector general’s office—which summarized his recollections in its 2018 report—the criticisms included the fact Morel had been doing favors for other people without asking for sex in return. The inspector general’s report did not indicate whether other participants in the meeting corroborated Zummer’s account.

Eventually, prosecutors agreed to allow Zummer to continue to search for new witnesses.

“For me, I was pretty much just standing up for Danelle,” Zummer said.

Osler, the law professor and former federal prosecutor, said that the kind of friction between Zummer and the federal prosecutors on the Morel case is commonplace at the DOJ. “People tend to have this view of the investigating agents and prosecutors like they’re offensive linemen and quarterbacks,” he told The Appeal. “But it’s not unusual for there to be real conflict there. And there should be, frankly, because it’s a prosecutor’s job to make sure bad cases don’t go to trial.”

But he also explained that federal prosecutors often have a cozier relationship with local district attorneys than they do with the FBI agents because they collaborate with local prosecutors on cases, team up on investigative work, and even split up forfeited assets after criminal convictions.

“You’re gonna need that person in the future,” Osler said. “If you are going to, as a U.S. attorney, go after a local county attorney, you better take the king down or not try. If you’re unsuccessful, you’re going to have a dangerous enemy and a lost partner that may prove to be necessary in the future.”

He added: “The U.S. attorney’s office and local officials often know each other really well, and sometimes they’re friends. The line being crossed in this case—the DA and U.S. attorney’s office on one side, the investigators on the other, is significant, and in some cases can be more significant than state-federal divide.”

Zummer’s team spent the next few years crisscrossing the South to locate more witnesses. His team interviewed more than 100 people and administered 39 polygraph tests. According to the FBI’s PowerPoint summary of the Morel case, at least 22 women identified as victims by federal investigators shared similar stories. One said Morel pressed his erect penis against her body and asked for sex. Another said Morel seemed turned on by track marks on her arm from heroin use, but that she ultimately arranged for Morel to have sex with a different woman instead. Other women reported performing oral sex on Morel, while another witness said he shoved his face into her crotch but she was able to escape. One woman stated that Morel performed oral sex on her.

Zummer said the story of one witness—who, according to FBI documents, Morel had asked to look up her skirt—stuck out in his memory.

“She was crying talking about it,” Zummer recalled.

Champagne, too, says he remembers another woman attempting to speak about her experience with Morel but becoming so upset she vomited. “Mike followed up on all of those leads—really, I’ve never seen anybody so tenacious and thorough as what he did,” Champagne said. “And there were roadblocks. I mean, roadblocks seemed to be thrown our way by the U.S. attorney’s office pretty much every step of the way after Jim Letten went.”

He added: “There were former judges calling, saying check into this woman check into that woman. Everything was a good case. All of a sudden, it all went away.”

Another woman, Monica Jackson, told The Appeal that, sometime between 2011 and 2012, she’d gone to Morel for help after a woman attacked her in the St. Charles Parish Courthouse. Frustrated by the incident, Jackson said she began crying in Morel’s office. She said Morel then walked up behind her and started rubbing her neck. She says he kept repeating that he could help not just her, but other loved ones that had gotten into legal trouble, too. Then she realized something.

“He was like, he was rubbing my shoulders, but really he was looking at my boobs,” Jackson said. “I just called him a fat bastard. He’s just gross, man, he’s a gross motherfucker.” She said she stormed out of his office and “never had any more encounters with him anymore.” Jackson later filed a lawsuit in federal court in Louisiana alleging that she was retaliated against by St. Charles Parish prosecutors for testifying in the federal grand jury’s investigation into Morel. Despite the fact that Jackson’s name had not been released to the public, she says she received anonymous phone calls telling her to “leave Harry alone,” and that someone placed a dead pigeon and cat by her front door.

The “defendants are all Caucasian and I am African-American, which is why I feel I am being targeted,” she stated in the suit. A federal judge dismissed her case.

In 2014, newly appointed U.S Attorney Kenneth Polite formally reopened the investigation into Morel. By 2015, Zummer felt he’d gathered enough evidence to potentially charge Morel using the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act. Back then, federal prosecutors in New Orleans regularly brought RICO charges against street gangs. But according to Zummer’s letter to Engelhardt, prosecutors conveyed their concern over how it might look if the public found out about the 2013 complaint Zummer filed with the inspector general regarding Harper and Capitelli’s home.

“There was a discussion about how the complaint would make the USAO look if it did [become public knowledge],” Zummer wrote. According to both the FBI PowerPoint summary of the Morel case and Zummer’s letters to Engelhardt, the Department of Justice’s Organized Crime and Gang Section approved charging Morel with RICO violations in early 2016.

But federal prosecutors, who had been in plea negotiations with Morel since May 2015, balked and cut a deal instead. Zummer later alleged to Engelhardt that prosecutors initially considered charges that carried significantly longer potential prison sentences. Eventually, however, Zummer says he was informed that the plea deal had been reduced to just one obstruction charge carrying a maximum of three years’ imprisonment. Zummer also wrote that Morel’s attorneys, including Ralph Capitelli and his son Brian, had also threatened to expose “bombshells” about the agency.

“I believe the Capitellis were testing the government’s case by alleging wrongdoing,” Zummer wrote.

In Louisiana politics, it’s who you know. So Harry won and we lost.

Monica Jackson alleged victim

Osler told The Appeal that it’s rare for federal prosecutors to put the effort into getting charges approved through the DOJ’s main office in Washington, D.C., and then not follow through on filing them.

“Often, you’re talking about writing a 50-page memo to support that case,” he said.

On April 5, 2016, the U.S. attorney’s office formally charged Morel with one count of obstruction for ordering Keim to destroy her memory card full of photos. The charge carried a maximum sentence of 36 months’ imprisonment. Morel pleaded guilty April 20; he was disbarred soon afterward at his own request.

In a news conference the day of Morel’s guilty plea, Polite stood before reporters—with Zummer in the room—and said Morel had preyed on women for decades—despite the fact that his office had not actually charged Morel with any sex-related crimes.

Morel “perverted his position of power to take sexual advantage of desperate women who needed help—and he did this over and over again,” Polite said. “Some of these women needed help enforcing child-support obligations. Others had children who were in trouble with the law. Others were in trouble with the law themselves and were at the end of their rope.” Polite said he felt confident his office had forced Morel to plead to the strongest charge available according to the evidence—obstruction—before also noting the “dogged determination of Special Agent Mike Zummer.”

Zummer’s boss, New Orleans’s FBI Special Agent In Charge Jeffrey Sallet, then spoke, noting that Morel had been the top law enforcement officer in St. Charles Parish for 30 years.

“And what did he do with that tremendous privilege and responsibility?” Sallet asked. “He used it to prey on some of the most vulnerable individuals to satisfy his own sexual interests. This joint investigation uncovered more than 20 victims spanning 20 years. Harry Morel is nothing short of a sexual predator.”

Polite took questions. Reporters asked why, if the FBI had identified so many victims, Morel had been allowed to plead to a single obstruction charge. Polite stated that he was confident his office had brought the right charges after taking Morel’s age and health into account, among other factors.

“We hear ‘more than 20 victims’ and ‘more than 20 years’—he was called a ‘sexual predator’ here today,” a reporter in the room said. “A three-year obstruction charge? How do you tell victims who had to go through this that that is justice?”

“What I tell them, again, is that this is a slow process at times,” Polite responded. “Unfortunately, it is oftentimes an imperfect process. In many of these circumstances, we are dealing with very significant evidentiary concerns. We are dealing with vulnerable victims that, if exposed to the scrutiny of the media, or the scrutiny of the courtroom, would prove to be very difficult witnesses and may ultimately lead to no justice for this defendant.”

Bennett Capers, a law professor at Fordham University and former assistant U.S. attorney in the Southern District of New York (Manhattan), told The Appeal he “could easily see how this would be a difficult case to prove at trial, and how a federal prosecutor would accept a plea to an obstruction charge to dispose of the matter.”

“Any case that depends on lay person witnesses can be difficult,” Capers said, “and the difficulties compound when you add allegations of sexual assault, especially with victims whose credibility will be questioned.”

Champagne said he credited Polite with pushing to reopen the case, given that he had newly been appointed as U.S. attorney. And, as a former prosecutor, Champagne also worried the accusers would have not fared well in front of a “top-notch defense attorney.”

“A lot of these women—they were truly victims—but I’ve always said, I mean, he picked his victims well,” Champagne said of Morel. “He picked women with low self-esteem, with substance-abuse problems, and issues. I think it’s the type of women he knew would never, ever dream of going public against a powerful district attorney.”

Jackson, however, says she couldn’t help but laugh at how paltry the single charge was.

“The justice system didn’t help us at all,” she told The Appeal. “They let him escape through the cracks. In Louisiana politics, it’s who you know. So Harry won and we lost.”

Carla was petrified to see Morel again. But someone needed to say something. Keim was dead, and she resolved that she’d finally confront Morel at the federal courthouse in New Orleans.

“I was promised by the FBI that I couldn’t be hurt by Harry Morel,” she said. Carla said she attended Morel’s sentencing hearing as an observer but did not testify. Tessie Keim told The Appeal her mother ultimately did not attend the hearing.

Zummer read the government’s “factual basis”—a statement of the facts detailing a crime and its particulars that is agreed to by the prosecution and the defense, which forms a basis on which a judge can accept a guilty plea from the defendant. The document focuses almost exclusively on Morel’s involvement with Keim (identified as “Individual ‘A’”), and notes that Morel used his office to solicit sex “between 2007 and 2009.”

Zummer believed that the factual basis excluded significant pieces of evidence uncovered during the investigation and appeared to minimize both the number of alleged victims who’d spoken to the FBI and the years in which Morel was accused of misconduct. Enraged, Zummer asked the FBI if he could file a letter with the court accusing the U.S. attorney’s office of prosecutorial misconduct. The FBI told him to seek approval from the inspector general’s office, which forwarded his request to another office in the DOJ that ultimately told Zummer to talk to his supervisors. Starting to run out of time, Zummer submitted his letters to the FBI’s “prepublication review” office, which clears any public statements by bureau employees. That office told Zummer it would not review his letter. (Later, in October 2018, the OIG stated that the advice Zummer received from the DOJ “misled and frustrated” him.) On Aug. 15, 2016 two days before Morel’s sentencing hearing, Zummer fired off a 31-page letter to Engelhardt anyway.

“The purpose of my letter is to report misconduct by the United States Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Louisiana (hereinafter “USAO”) which has affected the prosecution of Morel,” Zummer wrote. “I believe that the USAO’s misconduct has resulted in a plea agreement with Morel based more on its own interest in covering up its misconduct than in advocating for a just result. I believe these matters are of public concern and deserve First Amendment protections.”

On Aug. 17, 2016, Morel appeared for his sentencing hearing at federal court in New Orleans. More than 100 people sent letters to Engelhardt pleading for leniency. Some big names vouched for the disgraced prosecutor: Former Louisiana Attorney General Richard Ieyoub wrote that Morel had “helped thousands of Louisiana’s citizens” and that he made “a mistake which I know he deeply regrets.”

Morel then gave a brief statement.

“Your Honor, I want to thank the court in this matter, and I also want to apologize for my actions in this matter,” he said. “It’s unfortunate that I did what I did. I’m very sorry, and of course, I want to thank my family for the things that I—for sticking with me. It’s been tough on them—as tough on them as it’s been tough on me with the publicity and everything. So I want to thank those that wrote the letters, good friends that stood up for me. That’s basically it.”

Federal prosecutors also thanked Engelhardt for reviewing the letters sent that criticized Morel’s conduct, including Carla’s.

“We’ve appreciated that the Court has reviewed those letters that lay out some of what Harry Morel has done over the years as a district attorney, especially [Carla’s] and her discussion of what happened many years ago and the way that it’s impacted her since, that she was a desperate person seeking the assistance of Harry Morel and he took advantage of her,” Assistant U.S. Attorney James Baehr said during the hearing.

After comments from both Morel and the U.S. government, Engelhardt sentenced Morel to serve three years in prison, the maximum time allowed for his obstruction charge. (Engelhardt noted during the hearing that the government said Morel had “sexually victimized” numerous women “between 1986 and 2012,” but their stories would not affect Morel’s sentencing.)

Engelhardt added that the “very idea” of a prosecutor obstructing justice “would on its face” justify the three-year maximum sentence.

“For those of you who may think that Mr. Morel deserves a harsher sentence for his conduct, I must again remind you that the federal judges’ sentencing determination is limited by and to the charge or charges brought by the government—by the Department of Justice—that is, the United States Attorney for the district,” Engelhardt stated, adding that “any inquiries or complaints that the maximum sentence imposed today is just too low should be directed to those decision-makers and their discretion, not the judiciary.”

Morel served only 23 months of that sentence at a low-security facility in Seagoville, Texas, and at a New Orleans halfway house. He was released from federal custody in August 2018.

Upon hearing the length of Morel’s sentence, Tessie Keim said her family “took a breath, had our moment of human emotion and frustration and all of the things we felt, and then again we said, ‘OK, well we know that he’s going to get his own judgment day.’ So that’s where it is.’”

Zummer, meanwhile, was told he was suspended from investigative activity. On Aug. 30, 2016, he was told to move his desk to an empty nurse’s office on the second floor of the FBI building. He was also denied access to restricted or prohibited cases in the FBI’s computer system. Zummer sent a second letter to Engelhardt on Sept. 6. The letters sparked media interest in Zummer’s story: Local reporter Jim Mustian wrote a story for the Advocate noting that the then-sealed letter most likely contained “explosive and potentially privileged material, but, unlike the other correspondence sent to the judge, it has been withheld from the court record.” Mustian also reported that federal prosecutors had been fighting to keep Zummer’s complaints from going public—and had even asked the court to keep secret their legal arguments demanding that Zummer’s letter be sealed. The prosecutors argued that Zummer had revealed sensitive material—including information regarding 31 people (mostly FBI and U.S. attorney’s office officials) other than himself and Morel—and “breach[ed] his Employment Agreement.”

“Publicly filing these submissions, while not revealing the exact contents of the privileged portions, would still reveal information related to confidential communications that SA Zummer was not authorized to disclose to the Court or public,” FBI attorneys wrote.

On Sept. 15, Engelhardt issued an order in which he called Zummer’s allegations about the DOJ “troubling, to say the least.” He wrote that “the legitimate concerns of FBI Special Agent Zummer—that the Department of Justice is either unable or unwilling to self police lapses of ethics, professionalism and truthfulness in its ranks—are shared by the undersigned, particularly over the last few years.”

But Engelhardt did not enter either of Zummer’s letters into the case’s public record. Since then, the Department of Justice has never agreed to release either document without significant redactions. On Dec. 8 of this year, an assistant special-agent-in-charge at the New Orleans FBI field office argued in a declaration filed in federal court that releasing the full documents “could harm attorney-client communications within the FBI and the Department of Justice” and “chill” FBI “employees’ ability to have candid communications.”

On Sept. 16, 2016, Zummer emailed an assistant FBI special agent in charge and asked for an update on whether he might be placed back on active duty.

“Unfortunately, because you have taken the position that information you personally gather in the performance of your duties as an FBI Special Agent may be disclosed by you as a private citizen should you determine there is a need despite being instructed not to do so and without authorization, you have made it impossible for us to assign you investigative work,” his superiors wrote back. “This is not a punishment.”

On Sept. 30, Zummer was indefinitely suspended from the FBI, temporarily stripped of his security clearance, and escorted off the premises of the New Orleans office. On Oct. 17, Zummer emailed the staff of Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa, the head of the Senate Judiciary Committee, alleging that Capitelli and Harper’s relationship may have led to Morel’s lenient sentence. On Nov. 15—seven days after Donald Trump won the presidential election—Grassley sent open letters to the DOJ’s inspector general, Attorney General Loretta Lynch, and FBI Director James Comey.

“Mr. Morel has admitted to soliciting sex from female defendants and female family members of defendants during his time as the St. Charles district attorney,” Grassley wrote. “However, Mr. Morel was not charged with any sexual offenses. Rather, Mr. Morel received a three-year sentence in 2016 after pleading guilty to a single count of obstructing justice. AUSA Harper and Mr. Capitelli, who represented Mr. Morel, owned a condominium together until March 2013 when AUSA Harper transferred his ownership to his girlfriend.”

Grassley further wrote that the suspension of Zummer’s pay and security clearance after he sent his letter to Engelhardt “looks like it could be a misuse of the security clearance process to mask retaliation for protected whistleblowing.”

The senator’s letter received national media coverage at the end of 2016 but disappeared from the news quickly afterward. The #MeToo reckoning that began with the fall of the film producer Harvey Weinstein wouldn’t begin until the following year.

On Aug. 7, 2017, Zummer filed a federal lawsuit against the FBI, Sallet, and 10 other bureau employees for free speech violations. (He later added three more defendants in an amended complaint.) In court motions, the FBI argued that Zummer had been suspended legally and that the information he had tried to disclose, in fact, “belonged to the United States.” Zummer also filed a complaint with the inspector general’s office, but in the office’s June 2018 report, the agency said it found “insufficient evidence” that Zummer had been retaliated against and stated that Zummer had not gone through proper whistleblower channels. In March of this year, Sallet, one of the people who suspended Zummer, was promoted to executive assistant director of the FBI’s entire human resources branch.

The FBI fired Zummer on April 29. His suspension from the agency lasted nearly four years. In August, Zummer began working as the in-house counsel for an activist group called Protect the FBI, which aims to help “safeguard the FBI from partisan politics” by helping whistleblowers file misconduct complaints. On Oct. 8, the DOJ’s Office of Professional Responsibility filed a letter with the Louisiana Bar suggesting that that agency investigate Zummer for his conduct in the Morel case.

Zummer now says he’s lost faith in the FBI’s mission and believes that new accusers coming forward with information about Morel should get a lawyer if possible.

“I would have a really hard time telling people they should come forward at this point,” he said. “I think the FBI and DOJ— the people at the top—pay lip service. They claim the FBI and DOJ look out for victims, and look out for witnesses, but in my experience, the institutions do not bear it out.”

Morel’s accusers are also struggling. Carla says she’s still terrified that Morel might find her one day. She said she’s undergone therapy and had to work to heal the damage Morel did not just to her, but to her entire family.

“I quit seeing my parents,” she said. “I didn’t see my mom as much as I should have, because I was so angry. And I didn’t want to go to Saturday Mass with them, because I didn’t want to see Harry Morel. I missed time with my mother.”

She added: “It’s a shame. But it’s his shame—not mine.”