Why Would Prosecutors Refuse DNA Testing?

In this Oregon capital case, it could ensure that the state doesn’t execute the wrong man.

On March 20, 1998, Harriet Thompson was found dead in her Salem, Oregon, apartment. The scene was gruesome, “a scene from a slaughterhouse” the District Attorney would say — blood stains on the floor, bloody shoe-prints, bloody towels, a bloody bathroom and a broken, bloody knife. The police formulated a theory that the crime was a murder-robbery.

A week later, the police arrested Jesse Lee Johnson because he had some of Thompson’s jewelry, allegedly giving earrings to his girlfriend and selling a ring. Johnson admitted he had been in Thompson’s apartment — he knew her — but denied being involved in her death. At trial, prosecutors presented some forensic evidence — a cigarette butt, footprints and fingerprints — to argue that Johnson had been in the house that day and had killed Thompson. Prosecutors offered to let Johnson plea to manslaughter, which he turned down. He was then convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death.

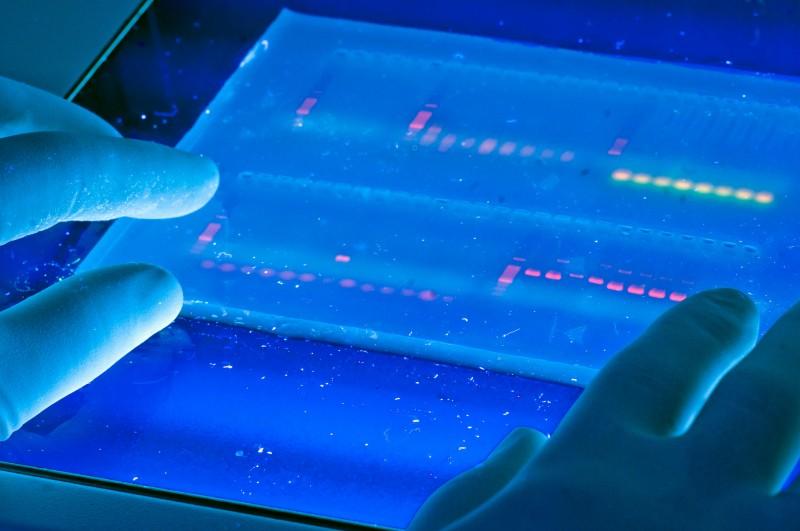

Johnson has maintained his innocence for twenty years. Now, his counsel, Steven Wax of the Oregon Innocence Project, is asking for DNA testing of 38 samples from the crime scene. Many of them were never tested; others were tested using an older DNA test that has fallen out of use because it is not as accurate as current methods. The Marion County District Attorney’s office is opposing any requests to test more evidence, arguing in their brief that “this is not a DNA case.”

Even though DNA testing has helped exonerate over 340 people, there are still prosecutors who oppose disturbing standing convictions, favoring finality over justice.

For example, St. Louis County Prosecutor Bob McCullough defended the capital conviction of Marcellus Williams even though post-conviction DNA testing pointed to a different person. McCullough’s office and the Missouri Attorney General’s office continued to argue that other evidence, mostly consisting of jailhouse snitch testimony, pointed to Williams’s guilt. Ultimately, the Missouri governor stayed the execution pending an investigation.

In another recent Philadelphia case, Anthony Wright faced execution for a rape and murder that he did not commit. Wright — who was only 20 at the time of his arrest — says he gave a confession after being threatened by the police. Post-conviction DNA testing, which the original prosecutor Lynne Abraham resisted, pointed to another suspect. Despite the fact that a judge ordered a retrial based on the DNA results, then-District Attorney Seth Williams prosecuted Wright again and lost.

And, even though DNA testing is the gold standard for convictions and exonerations, there are differences in how DNA evidence has historically been processed as well as how that evidence can be used and interpreted. In the early stages of DNA exonerations, the evidence was relatively simple — DNA from a rape kit, for example, definitively excluded the exoneree from the crime.

In Johnson’s case, the DNA evidence requires more interpretation because, as Johnson admits, he was in the apartment. Therefore, it would make sense that his DNA would be found on objects also in the crime scene. For example, some evidence was tested for DNA, but the results were not conclusive. Some DNA samples — like those from the bloody bathroom and the likely murder weapon — excluded Johnson, but law enforcement never matched the DNA to anyone else. Some DNA samples were mixed and difficult to process. Some DNA matched other people. And some DNA samples did match the defendant, but they could also have been present because Johnson had been in the apartment before. (The state used other evidence — like footprint matching — at trial, but the results were not only potentially tainted by law enforcement but have also been deemed unreliable by the scientific community.)

This is likely to be the next generation of DNA exonerations — cases where the DNA can point to other suspects or cast appreciable doubt on a conviction.

Last Friday, Johnson’s counsel argued in favor of additional DNA testing while the DA’s office defended their position that the current Oregon law does not apply to Johnson’s case because, they argued, there was not enough to show that the results would fully prove Johnson’s innocence. Steve Wax, Johnson’s legal counsel, argued that the Oregon statute only required a “reasonable possibility” that the evidence points to innocence. It would be impossible to prove otherwise until the testing is complete, as Wax explains. Via email he told me after the hearing, “Seven exclusions of Mr. Johnson’s DNA from items at the murder scene raise significant questions about the conviction that we are hopeful further testing could answer.”