Why Are Prosecutors Still Seeking to Execute People Who Have Innocence Claims and Untested DNA?

In these last two months of 2019, one man has been executed and two others are facing execution despite claims that they can show they don’t belong on death row.

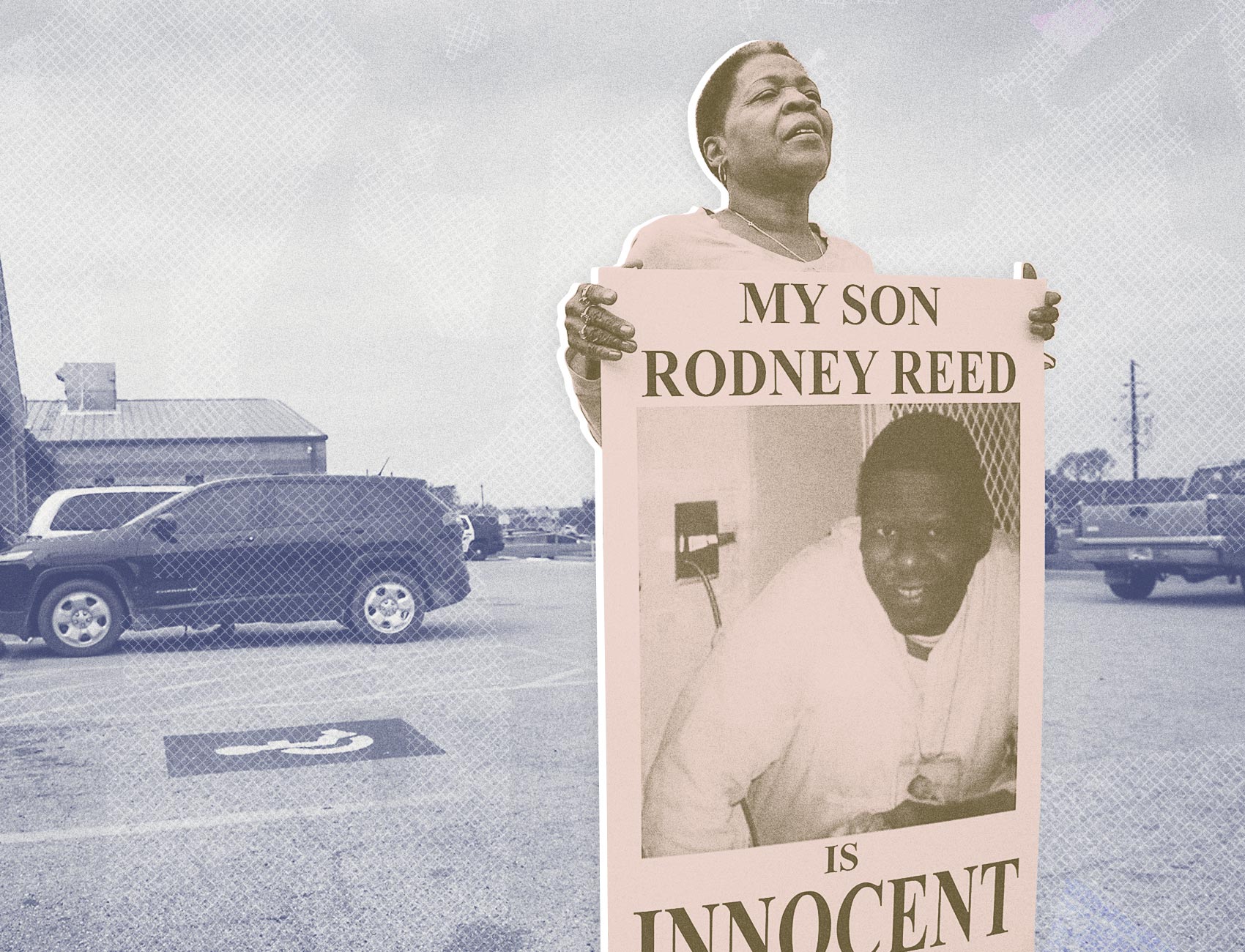

On Nov. 15, Texas’s highest criminal court postponed Rodney Reed’s execution indefinitely to allow time for a Bastrop County trial court to review evidence that he says shows he never murdered 19-year-old Stacey Stites. For two decades, his attorneys have argued they could prove his claim with DNA testing of several items found near her body, including the murder weapon. Their attempts, which faced opposition from prosecutors and the courts, had been predominantly unsuccessful until now.

Reed, however, is hardly alone in his struggle to prove his innocence. In these last two months of 2019, one man has been executed and two others are facing execution despite claims that they can show they don’t belong on death row. On Nov. 13, Georgia executed Ray Cromartie despite the existence of evidence, including DNA, that was never tested. And Florida was scheduled to execute James Dailey on Nov. 7, though the courts granted him a stay of execution that expires on Dec. 30. He was convicted largely on the testimony of jailhouse informants known for their history of police cooperation.

The United States has a long history of sending innocent people to death row. Since 1973, the beginning of the modern death penalty era, 166 people sentenced to die have been exonerated. And according to a 2014 analysis of past exonerations, approximately 4 percent of people, or roughly 110 prisoners, on death row are innocent.

But once a person is sentenced to death, proving innocence, no matter the evidence of innocence or misconduct, is challenging. This is intentional, experts say. “The system is designed to carry out executions, not to correct errors,” Robert Dunham, executive director of the nonpartisan Death Penalty Information Center, told The Appeal.

This is due to several reasons. In most cases, prosecutors are determined to make convictions stick, and due to procedural rules, judges have discretion over what to allow as evidence and which claims merit sending a case back for a new trial. Then there are laws, both state and federal, that make it difficult for death row prisoners to win innocence claims. As appeals climb through the courts, the window to prove innocence becomes tighter. “What you need is overwhelming evidence, and oftentimes overwhelming evidence still isn’t enough,” said Dunham.

DNA, which is facing new attention in Reed’s case, is never a sure thing. Available in less than 10 percent of cases involving a violent crime, securing testing of the material usually means fighting the prosecution and then hoping the courts rule favorably.

In many of the 20 cases of exonerations by DNA testing since 1973, people came within days of running out of time. For Cromartie, any chance of exoneration ended with his execution.

“It shows how arbitrary it is,” his attorney, Shawn Nolan, told The Appeal. “People get executed in this country because of statute of limitations issues and things like that or because of bad lawyering. It’s totally random.”

Ray Jefferson Cromartie

In 1994, two men walked into the Junior Food convenience store in Thomas County, Georgia. One raised a gun and shot the clerk, Richard Slysz. An Adidas shoe print in the mud and a fingerprint found on a piece of cardboard outside matched Cromartie and placed him at the store, according to the state. Until his death, Cromartie maintained that he didn’t pull the trigger. At his 1997 trial, his co-defendant, Corey Clark, sealed his fate by pinpointing him as the killer.

In exchange for his testimony, prosecutors dropped murder charges against Clark and gave him 25 years in prison; he was out on parole in 11. The getaway driver, Thaddeus Lucas, also testified for the state and took a plea deal. Cromartie, however, turned down a life sentence with the possibility of parole after seven years, believing he could convince the jury he wasn’t the gunman.

Beginning in 2018, Cromartie’s attorneys asked the courts for DNA testing on never before tested items, including the murder weapon and clothing believed to be worn by the shooter. Nolan said testing hadn’t been requested sooner because the technology to perform it wasn’t available yet. And under Georgia’s DNA testing law, defendants can only ask for testing one time, rendering the issue moot if the first test doesn’t return useful results.

Georgia Attorney General Christopher Carr and Thomas County District Attorney Ray Auman opposed the testing, arguing that the request had come too late and would not show that Cromartie was innocent. The courts agreed. Still, Cromartie had an unlikely ally in his corner.

Slysz’s daughter, Elizabeth Legette, wanted the evidence to be tested, writing to the Georgia Supreme Court in October, “I have read a lot about the case and I believe that there are serious questions about what happened the night my father was murdered and whether Ray Cromartie actually killed him.” She added that the prosecution had never responded to her requests to discuss her position on the testing.

Then a week before the execution, Lucas, the getaway driver, wrote an affidavit stating that he had heard Cromartie’s co-defendant, Clark, tell a friend he shot Slysz in the face. “Over the last couple of weeks I have read about the case in the news and it has made my very angry because the story is not the truth,” he wrote. “I keep hearing that Jeff Cromartie is the shooter and I know that’s probably not true.”

Lucas’s statements weren’t strong enough to sway the courts, which found them incredible and said that Cromartie’s legal team should have obtained them earlier. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review Cromartie’s claims and he was executed by lethal injection last week.

Nolan, Cromartie’s attorney, told The Appeal that Georgia executed an innocent man.

“It is so sad and frankly outrageous that the state of Georgia executed Ray Cromartie tonight after repeatedly denying his requests for DNA testing that would have proven he did not kill Richard Slysz,” he said in a statement following the execution. “In this day and age, where DNA testing is routine, it is shocking that Georgia decided to end this man’s life without allowing us, his attorneys, access to the materials to do these simple tests.”

Legette agreed, releasing a statement to the media saying she had “not been treated with fairness, dignity, or respect, and people in power have refused to listen to what I had to say. I believe this was, in part, because I was not saying what I was expected to say as a victim.”

James Milton Dailey

For nearly 35 years, Dailey has said he didn’t kill 14-year-old Shelly Boggio in the waters of Indian Rocks Beach, Florida, in 1985. But his story was no match for three jailhouse informants who testified at his 1987 trial they had heard Dailey make incriminating statements about his involvement in Shelly’s death.

According to the prosecution, Dailey and his friend, Jack Pearcy, had taken Shelly out to the beach, stabbed, then drowned her. When her naked body was pulled from the Gulf of Mexico, it was found mutilated with 31 stab wounds.

Pearcy, who received a life sentence for the crime, has been inconsistent in his statements about Dailey’s presence. In 2017, he signed an affidavit stating, “I alone am responsible for Shelly Boggio’s death.” He backtracked at a court hearing the following year, testifying under oath that what he said was false.

Over the years, Dailey’s defense team has raised several issues that they say call into question the reliability of his conviction. Among those, they have said that a Pinellas County Sheriff’s detective showed county jail prisoners news articles about Shelly’s murder and asked them if they had heard Dailey say anything about his involvement. That detective had earlier said he interviewed 15 prisoners about whether they had heard Dailey say anything incriminating, a practice he considered standard.

Dailey’s attorneys have also attacked other elements they say are key to their client’s case, but to no avail. This includes testimony that Pearcy was alone with Shelly for at least 90 minutes on the night she was killed, but the courts ruled that testimony unreliable. Many of Dailey’s claims have failed because of procedural rules.

Most recently, attorneys accused the Pinellas County state attorney’s office of prosecutorial misconduct, charging that it withheld vital evidence. Listed among that evidence is a police report establishing that Pearcy and Shelly were alone at the time of her murder, evidence of favorable treament given to the jailhouse informants, and the discovery that Pearcy had killed Shelly because she teased him about not being able to sexually perform.

Last month, a judge postponed Dailey’s execution until Dec. 30, while his attorneys, who were appointed on Oct. 1 to mitigate a conflict of interest with his previous lawyer, file further documentation on what they say is newly discovered evidence that will exonerate him. Florida leads the nation in death row exonerations. Since 1973, there have been 29; for every three executions, one person is freed.

Rodney Reed

Reed was largely convicted on three sperm cells found inside Stites, whose body was found by the side of a road in Bastrop County, Texas, in April 1996. At his 1998 trial, the prosecution argued that the sperm’s presence proved that Stites had been strangled with a belt right after Reed raped her. Reed countered that he and Stites had been having a consensual affair and his sperm were found because they had sex sometime after midnight the day before she was found dead.

In the two decades since he was sent to death row, medical experts—including the examiner who testified at trial that the sperm were evidence of sexual assault—have said the three sperm do not show that Reed raped Stites then killed her. This has been bolstered by statements from forensics experts challenging the state’s sequence of events.

Instead, Reed’s attorneys have alleged that Stites was murdered by her fiance, Jimmy Fennell. A former police officer, Fennell was released from prison in 2018 after being convicted of kidnapping and improper sexual contact with a woman in his custody in 2007. He has always denied killing Stites, but his inconsistent statements to police, along with statements from those close to him claiming he implicated himself, have cast suspicion on his involvement in her death.

According to a federal civil rights complaint, Fennell said on numerous occasions that he would kill Stites if she ever cheated on him, at least one time specifying it would be with a belt.

To date, prosecutors and the courts have refused to allow testing of the belt that was believed to have been used to strangle Stites. Bastrop County District Attorney Bryan Goertz has argued that the belt, along with other items, is not fit for testing because it has been contaminated by its various handlers over the years. And even if it wasn’t, he said it’s not enough to prove that Reed is innocent. Texas’s courts have agreed.

The case has been returned to the Bastrop County trial court for further consideration, but it remains to be seen whether DNA testing will be granted. “Postconviction DNA testing is not only to exonerate, but also to identify the guilty parties,” Reed’s attorney, Bryce Benjet, told The Appeal. “We know that the murderer held both ends of the belt, wrapped it around her neck and used it to strangle her. We know that in the process of doing that, cells on the perpetrator’s hands would have transferred to the ends of the belt.”

It’s likely that innocent people will continue to be executed until legislators greenlight reforms that make it easier for people to successfully challenge their convictions, experts say.

“If there’s DNA evidence, test it and mandate that it be tested,” said Dunham of the Death Penalty Information Center. “If there is other evidence suggesting innocence, hear it. And eliminate the procedural obstacles that have been created to intentionally make it difficult for the courts to do real justice.”

To do so, legislators must pass new laws that make it easier for death row prisoners to successfully challenge their convictions and roll back the laws that have devastated their chances thus far. High on the list is the Clinton-era Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, a law that has made it nearly impossible for people to win relief from the federal courts.

Brandon Garrett, a Duke University law professor and an expert in wrongful convictions, told The Appeal that it’s also vital that the government enacts reforms that make it easier for people to win DNA testing. Currently, each state has laws governing which items qualify for testing, but the decision on whether they meet that criteria is left with the courts.

“There should be stronger constitutional law ensuring such a right,” Garrett said. “We know that innocent people face execution and that DNA can prevent such terrible miscarriages of justice.”

Kirk Bloodsworth, the first person sentenced to death to be exonerated with DNA testing, told The Appeal, “It’s a crapshoot and nobody’s life should be dependent on that kind of crapshoot. Not even a little. We don’t need to do that in this country anymore.” He added, “If it could happen to me, it could happen to anyone in America.”

An earlier version of this article misstated the status of James Dailey’s execution date. The courts granted him a stay of execution that expires on Dec. 30.