Newsletter

‘This Is How Easy It Is For Someone To Be Wrongfully Convicted’

Uriah Courtney was sentenced to life in prison for a crime he didn’t commit. His conviction was overturned due to DNA evidence.

‘This Is How Easy It Is For Someone To Be Wrongfully Convicted’

by Meg O’Connor

Uriah Courtney was sentenced to life in prison for a crime he didn’t commit. In 2004, a teenage girl was sexually assaulted by a stranger on the streets of Lemon Grove, a city in San Diego County. Prior to being assaulted, the victim noticed a man staring at her from an old, light-colored truck with a fake wooden camper. When the victim spoke with police, she told them she assumed the man from the truck had attacked her, and that her attacker was a white male in his 20s.

Police put out an alert for a vehicle matching that description. Eventually, someone saw a light-colored truck with a fake wooden camper in that area and called the police. The truck belonged to Courtney’s stepfather. He used the truck for the business where he and Courtney worked and allowed his employees to use the truck as well. Courtney’s coworker had the truck parked in his driveway in Lemon Grove when someone called it in. Both the coworker and Courtney’s stepfather were too old to match the victim’s description, but Courtney wasn’t.

Police presented a photo of Courtney to the victim in a photo lineup. She picked out Courtney, saying she was, “Not sure, but the most similar is number 4,” according to the California Innocence Project, a nonprofit organization that helps free innocent people and overturn wrongful convictions.

An eyewitness also identified Courtney. Based on this, Courtney was arrested for kidnapping and rape. In 2005, a jury found him guilty and a judge sentenced him to life in prison.

Years later, the California Innocence Project took on Courtney’s case and got the San Diego District Attorney’s office to submit the victim’s clothing for DNA testing. The DNA on the victim’s clothing did not match Courtney. But it did match a man who lived three miles from the crime scene, looked like Courtney, and had been convicted of a sex crime.

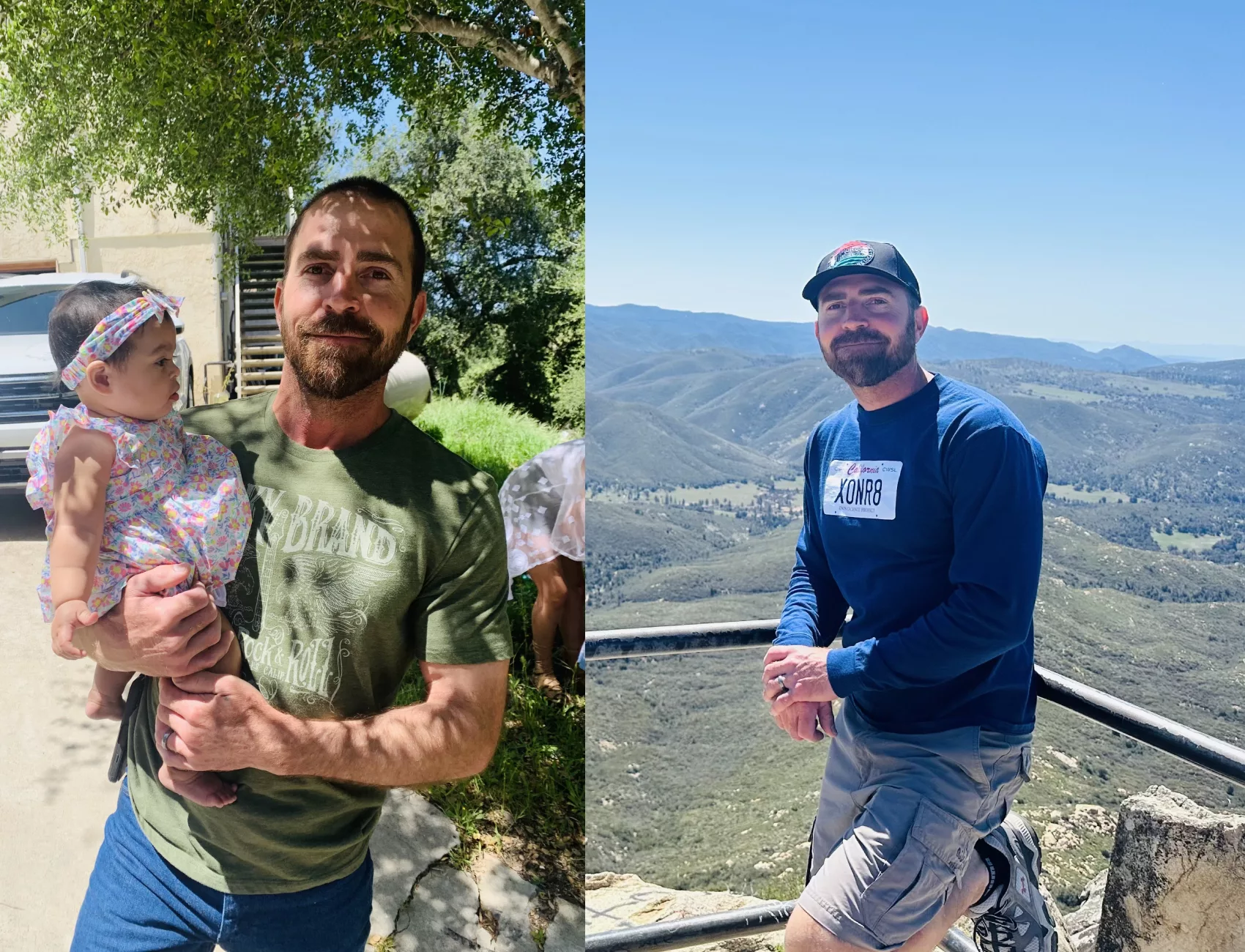

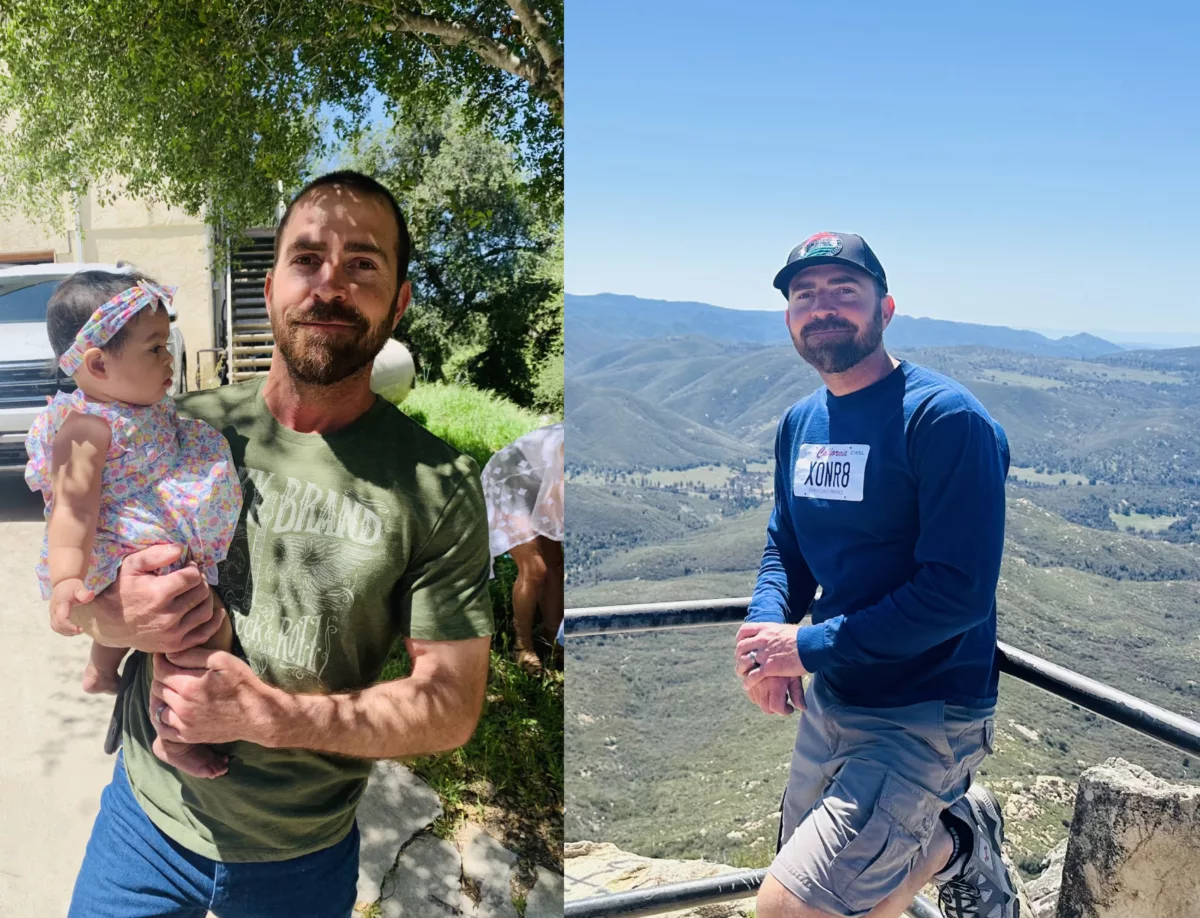

Courtney’s conviction was vacated in 2013. He spent eight years in prison. We spoke with Courtney about his experience and what he wants people to know about wrongful convictions.

“I could have been in prison for the rest of my life if there wasn’t DNA evidence,” Courtney said. “Sitting in prison all those years. I just felt hopeless. I wished I could die. When I hear about other people behind bars still awaiting their day back in court, or someone who was just released due to DNA evidence, it hits me from time to time. I try not to think about it.”

The California Innocence Project recently launched a true-crime podcast that highlights cases of wrongful convictions and features interviews with exonerees. The interview below has been condensed for clarity and length.

The Appeal: Can you tell us what happened to you?

Uriah Courtney: I was already caught up in the system. I was a drug addict. I’d been in and out of jail for minor offenses. Then later I had some more serious drug offenses. I was in a work furlough program. I didn’t follow it so I had a warrant out for my arrest.

I wound up getting arrested in Austin at my son’s mother’s house. I sat in Travis County jail for a couple of weeks before I was extradited to San Diego. I was called into court one day. A court-appointed attorney was there to represent me. I assumed I had been called into court because of my drug-related charges.

The judge started reading off these charges—robbery, kidnapping, rape, this and that. My legs just about buckled beneath me. It was all I could do to stay on my feet. I said something to the court-appointed attorney. He shushed me, said we’d talk after the hearing. We did, but he didn’t know anything.

The whole time I sat in the jail and all the court hearings leading up to the trial, I believed that someone would call me up, a detective or something, and say, ‘Sorry we made a mistake. You can go on your way.’ I really believed that, I was so naive. I just had no idea how screwed up the system actually is.

I wound up getting convicted and sentenced to life in prison. It was the worst day of my life. I was pacing and praying when the jury was deliberating. Praying the jury would see the truth.

TA: What was going through your mind when you heard your sentence?

UC: It’s hard to articulate. Words don’t do it justice. I was in a state of shock. I was devastated. I cried. I was depressed. I wanted to die. I wanted to live. I was angry. I was angry at the victim, angry at the detective, angry at the world. Eventually, I was able to not be angry at the victim. My family supported me throughout the whole ordeal. I was crushed. I was so confused. I didn’t know why this was happening to me.

TA: Why didn’t the police test the evidence sooner?

UC: When the attacker grabbed the victim, the victim struggled to get free. In the process, the attacker’s face rubbed against her clothing. The attacker digitally penetrated her. When the victim got away from him, she was picked up by a passerby. The driver took her home and called the police. During that time the victim took a shower and put her clothes in a laundry basket.

The police did fingernail scrapings, they took the clothes, they looked for semen. But they weren’t able to pull anyone else’s DNA from that. The type of DNA testing that was eventually done in my case—I don’t think it was really being used much at the time.

Years later, my stepdad contacted the California Innocence Project. At the San Diego District Attorney’s office, there was an assistant district attorney who worked with the California Innocence Project on cases where a conviction shouldn’t have happened. I cannot say enough good things about him or the California Innocence Project.

Eventually, they agreed to retest the evidence. They were able to extract male DNA from the areas of her skirt and tank top that had come into contact with her attacker. They compared it to my DNA and I was excluded as the male donor of that DNA.

I thought, ‘This is great, this will prove my evidence, and everyone will know it now.’ But the California Innocence Project told me I’d probably need to go to another trial unless they found an owner for that DNA.

It was finally entered into CODIS and it was an instant match. He was in the system for another sexual assault—after the one he committed that I was accused of.

If they had gotten things right to begin with there would have been one less victim out there. And I wouldn’t have spent eight years in prison.

Sometimes I ask myself, ‘How can these people look at themselves in the mirror? How can they sleep at night?’ It’s a condition of being human, I guess. Humans are sinful. There will always be people like this in the world.

I think—my background, my history prior to all this was not good. And I think because of that, they just wanted to get a “bad person” off the street no matter what it took. Even being dishonest. I just find it hard to believe that they didn’t see the flaws in their own case.

TA: What happened to the real attacker?

UC: They tracked him down. But the DA decided not to go after the guy because the statute of limitations on the rape case ran out. And they believed making the victim go through another trial was too much. He’s not in prison now, but he’s a registered sex offender.

That’s one of the things that still upsets me. The victim did not get justice. I got forced into this whole ordeal. I’m out of prison, but I’m still traumatized. There’s still injustice.

Nobody has been held accountable for this. Not the DA, not the detective, and not the perpetrator.

TA: Do you know how the victim has reacted to this?

UC: I was desperate to meet the victim after I was officially exonerated. I was hoping to tell her—whether it meant anything to her or not— I forgive you. It’s not your fault.

Unfortunately, she didn’t want to meet. The prosecuting attorney was desperate to hold on to her conviction. She came up with multiple theories for how the DNA evidence could have come about—maybe it was contaminated by the clothes hamper, or some guy sneezed on the bus, or the California Innocence Project tampered with evidence. And the victim said she still thought I was the guy that attacked her. I was pretty disappointed by that.

I’ve been out for nine years now. Some days it still feels like I just walked out those prison doors. And some days it feels like it’s been almost 10 years. I got married in 2016 to a strong, wonderful woman. I’ve got PTSD. Sometimes I’m still angry. I lost eight years of my life. Sometimes I think of what could have happened if I wasn’t arrested. What I was accused of could have gotten me killed in prison. I lived in fear daily. It wasn’t a matter of if someone was going to come after me, but when. Because people that are in prison for sex crimes, bad things happen to them.

I found myself in a unique situation, where part of me wanted to see bad things happen to those types of people, but had to remind myself—what if that guy’s in the same boat as me?

TA: What can people do to help or support you?

UC: I wrote a book. For me personally, I don’t really gain anything off the book. Writing it was just therapeutic. I wanted to get my story out there. If someone wants to support me, it’s called Uriah Courtney Exoneree.

The best thing anybody can do is to educate themselves on what is really going on. This is how easy it is for somebody to be wrongfully convicted. And whatever state you’re in, support your state’s innocence project. DNA tests are expensive. So are prison visits. All that stuff costs money. The more funds they have, the more attorneys they can hire, the more exonerees there’s gonna be.

ICYMI — from The Appeal

New York’s predatory “family policing” system routinely skirts the rights of parents and rarely substantiates abuse or neglect allegations. The agency primarily targets low-income families and disproportionately those who are Black or Latino, reports Daniel Moritz-Rabson in a story produced in partnership with the New York Civil Liberties Union.

“Family police” can carry out “child welfare” investigations without informing parents of their rights to speak to an attorney or to deny them entry into the home. “Family Miranda” requirements would protect parents from overreach, writes Sarah Duggan.

In the news

Your favorite skin care product has a dark secret. For over 20 years, Dr. Albert Kligman experimented on people incarcerated in Pennsylvania’s Holmesburg Prison. Tretinoin, a popular anti-aging cream, was a direct result of Kligman’s torturous and unethical experiments. [Tamar Sarai / Prism Reports]

Jordan Neely was a homicide victim. But media coverage that relied heavily on anonymous police sources painted him as the villain. [Matt Shuham / Huffington Post]

The New York City Department of Corrections is eliminating a $17 million program that offers people on Rikers Island group sessions on emotional regulation, financial literacy, and more as part of Mayor Eric Adams’ budget cuts. [Maya Kaufman / Politico New York]

Migrant aid organizations in El Paso are seeking donations and volunteers to help with the expected rise in people crossing the border after Title 42’s expiration last week. El Paso Matters published a list of ways to help migrants and asylum seekers. [Priscilla Totiyapungprasert / El Paso Matters]

Surveillance footage shows a Walgreens security guard killing Banko Brown, a 24-year-old community organizer for Black transgender youth. Brooke Jenkins, the San Francisco district attorney elected to replace Chesa Boudin, says the shooting was “reasonable” and she will not be filing charges. [Sam Levin / The Guardian]

Chris Blackwell has experienced plenty of inhumane treatment during his two decades in prison. But nothing prepared him for the horrors he witnessed while detained in county jail for two weeks in December. [Chris Blackwell / The New York Times]

That’s all for this week. As always, feel free to leave us some feedback, and if you want to invest in the future of The Appeal, donate here.