Brazilian Man’s Suicide Sends Shockwaves Through ‘Inhumane’ ICE Detention Center

Detainees at New Mexico’s Torrance County Detention Facility recently launched a hunger strike, motivated in part by the August death of a 23-year-old asylum seeker in custody.

SÃO PAULO – The August suicide of a young Brazilian man detained at a New Mexico Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facility has spurred new calls for action among immigrants’ rights advocates and fellow detainees, who recently launched a hunger strike to protest alleged abuse and inhumane conditions.

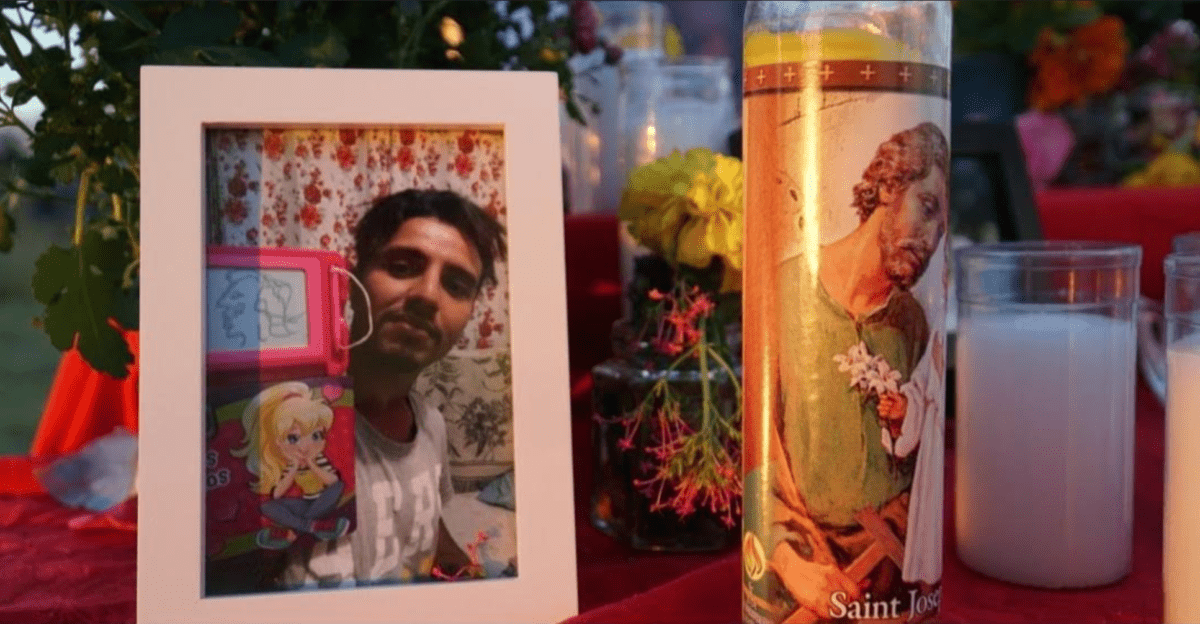

Kesley Vial, a 23-year-old asylum-seeker from Brazil, was found unconscious in his cell at the Torrance County Detention Facility on Aug. 17 and taken to the University of New Mexico Hospital. He died a week later. Though an official cause of death has yet to be determined, the American Civil Liberties Union and New Mexico Immigrant Law Center—who are in contact with Vial’s family and with other detainees at the facility—say that Vial died by suicide.

Vial had been in ICE custody for around four months at the time of his death. Border patrol agents first detained him on April 22 in Texas, following a border crossing. He was initially held at an immigration center in El Paso, before being transferred to Torrance. The privately operated ICE facility in Estancia has attracted national controversy amid officially documented reports of safety risks and unsanitary conditions, with the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) going so far as to call for the immediate removal of all detainees earlier this year.

Vial’s death has compounded the suffering that many immigrants in ICE custody say they’ve faced at Torrance. Some fear that another tragedy could unfold at any moment. Detainees and advocates now tell The Appeal that the only way to achieve justice is to shut the facility down.

Vial was born in São Paulo, Brazil’s largest city, and raised by his grandmother after his mother moved to the United States when he was a child. Vial spent part of his childhood in Galileia, a small city in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, before moving to Camboriú, in the state of Santa Catarina.

Victor Venâncio, a former classmate of Vial’s who still lives in Brazil, recalled studying together in 2008.

“He was a cool kid. A number of our childhood friends ended up going to the United States,” Venâncio told The Appeal in Portuguese during an interview.

After finishing school, Vial worked at a store and liked to play the guitar in his free time, a cousin told The Appeal in messages over social media. She asked to remain anonymous because she’d been advised not to speak to the press while Vial’s family considers its legal options. Vial was a “dreamer” and a “hard-working guy who could not harm anyone,” she said.

On April 22, border patrol agents detained Vial in El Paso after he crossed the border. He was taken to an immigration center and was kept there for a week.

At the detention facility in Texas, Vial was placed in a cell with an acquaintance from Brazil who had also been detained after crossing the border.

“I had not seen Kesley for seven years,” the man told The Appeal in Portuguese during an interview. “We had been friends in Galileia years ago.”

The man, who has since been released from ICE custody and asked to remain anonymous due to legal concerns, said that the facility in Texas was “tough,” and had “too many immigrants and only a few agents to handle all of them.”

After a few days in custody, the two old acquaintances parted ways. The friend was sent to another detention center in the South, where he said conditions “were much better.”

Vial, on the other hand, was taken to one of the worst ICE detention centers in the country. Indeed, since 2019 when Torrance began to receive asylum-seekers and immigrants, it has been the subject of intense criticism from detainees, non-governmental organizations, and federal officials alike.

In 2021, Nakamoto Group, ICE’s official inspection contractor, reported several issues at Torrance, including “numerous instances of sanitation and safety concerns” related to food preparation and chronic staff shortages.

“The current staffing level is at fifty percent of the authorized correction/security positions. Staff is currently working mandatory overtime shifts,” the report said.

Two detainees told inspectors they had “submitted sick call slips and had not been seen by medical staff.”

In February 2022, the Department of Homeland Security’s OIG carried out a surprise inspection at Torrance that resulted in an alert the following month recommending the immediate removal of all detainees from the facility.

The OIG report highlighted “critical staffing shortages that have led to safety risks and unsanitary living conditions” at Torrance. Inspectors identified serious problems concerning sanitation and hygiene.

But ICE did not accept OIG’s recommendation to remove detainees from the facility. Immigrants’ rights advocates say the situation did not improve after the report.

“The OIG does not have the power to order ICE to do something,” said Rebecca Sheff, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU of New Mexico, in an interview with The Appeal. “The same conditions persisted and in some cases they got worse. Those were the conditions that Kesley faced there.” Sheff said less than 100 detainees remain at Torrance, most from Latin America, but also from Turkey and other countries.

Detainees have also reported being denied information about their immigration cases. This has led to a form of indefinite detention for some people, during which they have no idea how long they might remain incarcerated, or whether or not they’ll be deported. Vial tried repeatedly to get updates on his case, but couldn’t get clear answers, according to Sheff.

“At some point after he was ordered to be deported, he was put into a plane,” she said. “But without any explanation he was taken out of it later and brought back to Torrance.”

After returning, Vial began “manifesting psychological problems,” a fellow Torrance detainee from South America, who requested anonymity due to fear of retaliation from ICE, told The Appeal in Spanish. A short time later, Vial was found unresponsive in his cell.

Vial’s death sent shockwaves through Torrance. The South American detainee said he had “a nervous breakdown” after learning of the suicide.

“We just cannot understand why they kept him here for four months,” he said. “That was an evidence of this place’s incompetence to handle mental health issues. We fear it can happen again.”

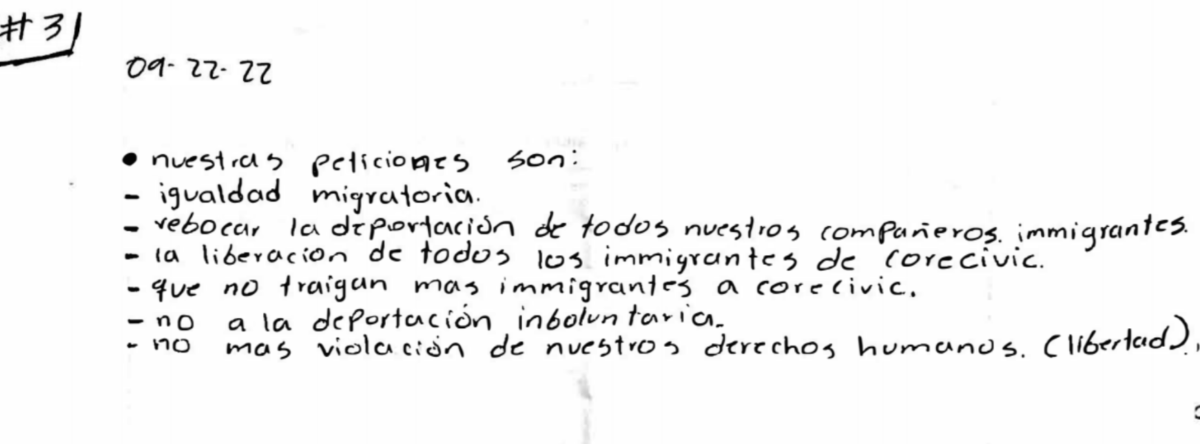

In September, a group of detainees launched a hunger strike, motivated in part by Vial’s death and the continued refusal of officials to make changes.

Orlando de los Santos Evangelista, a 39-year-old native of the Dominican Republic, helped organize the strike. Reached by phone at Torrance in late September, he told The Appeal that Vial’s death had strengthened their resolve to fight against involuntary deportation and for their freedom.

“Even after that, the ICE authorities did not consider that things ran out of control and that they should release us,” de los Santos Evangelista said in Spanish. “We understood that they do not have a heart and they do not care about our safety.”

De los Santos Evangelista has been detained at Torrance since July 18, and said he has suffered “verbal and psychological abuse” on a daily basis. After starting the hunger strike, officers threatened to put the strikers in a small, isolated room, he said.

In a letter released on Sept. 22, the strikers wrote that on the day before Vial’s suicide attempt, an official came into a pod and told detainees that “everyone is staying locked up in here for up to two years.” The letter suggested the official had made similar threats to other pods, and that Vial had killed himself “because of the stress” the official had caused.

Earlier this week, the strikers announced that they had temporarily suspended their protest after some participants allegedly disappeared in the middle of the night. An advocate for detainees with the New Mexico Immigrant Law Center told the Santa Fe New Mexican that some strikers had been targeted in retaliation for calling attention to the conditions at Torrance.

Both ICE and CoreCivic have denied reports of a hunger strike, with a spokesperson for the private prison company claiming in a statement that “not one detainee has missed a meal.”

Even after Vial’s death, the ACLU continues to receive complaints about “atrocious” conditions, including clogged toilets and sinks, cells dirty with human feces, a lack of access to drinking water, and detainees who cannot get medical attention for more than 24 hours after suffering a medical emergency, according to Sheff.

The detainee from South America, who has been detained at Torrance for more than two months, told The Appeal that he regularly received clothes that were poorly washed and stained, which caused skin infections. He described food that is nearly inedible and sometimes served raw.

“Given that I cannot stand it, I have been losing weight,” he said. “The last time I checked, I had already lost 24 pounds.” He recounted seeing a fellow detainee shivering with fever as staff ignored his calls for help. The man was taken to the doctor after seven hours, he said.

“The conditions are inhumane,” the detainee said. “I’m an immigrant, not someone who perpetrated a crime. There’s no reason for keeping me detained.”

Although Vial’s death led to renewed scrutiny of longstanding issues at Torrance, advocates say they have little hope that ICE will make changes voluntarily.

“The government cannot detain those people as a way of punishing them,” said Sheff. “They’re sending a message … Don’t come because we’ll treat you terribly. That is not acceptable under the law.”

Weeks after Vial’s death, his family and friends organized a crowdfunding campaign to help pay for his remains to be moved to Connecticut, where members of his family now live. The effort raised nearly $20,000, enough to pay for Vial’s body to be transported and to fly his grandmother from Brazil to be with the family.

In September, they held a velório—a Brazilian wake—for Vial. Photos posted on social media show grieving family members gathered around an open casket, with some, including Vial’s mother, giving him a last kiss. After 19 years apart, she was finally reunited with her son—if only to say goodbye.