The Push to End ‘Punishment Fever’ Against People With HIV

Advocates say laws that land people with HIV on the sex offender registry are outdated and dangerous.

Every five years, Mark Hunter has to pay around $300 to have his picture displayed in the newspaper and notices mailed to his neighbors, informing them that he is a sex offender. While on parole, he said, he pays about $60 a month in fees and has to attend a sex offender treatment class. His crime? In 2008, he was convicted of failing to tell two ex-girlfriends that he was HIV-positive.

Though neither partner contracted HIV, Hunter was still convicted under Arkansas’s HIV exposure law, which requires those who know they are HIV-positive to disclose their status to sexual partners. Sentenced to a dozen years in prison, he was released in 2011 after serving almost three.

But now, he must register as a sex offender, incurring the same obstacles, humiliation, and costs many others on registries face.

In Louisiana, where he now lives, Hunter’s driver’s license has “sex offender” written in capital letters under his photo, per the state’s registry requirements.

“When I saw it on my license, that was one of the most hardest things ever,” said Hunter, now 44. “Those two words on my license are still a hindrance to the life I want to live.”

Lousiana, Arkansas, Ohio, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Washington State require, or authorize courts to require, those convicted under HIV criminalization laws to be on the sex offender registry, according to the Center for HIV Law and Policy. Advocates, who condemn the statutes as ineffective, stigmatizing, and unscientific, are working to modernize the laws in the courts and state legislatures.

But even some of the fixes fall short, they say, including an amendment to Louisiana’s law that was enacted last year that removed biting and spitting as specifically identified means of transmission. Disclosure of HIV status is still required.

“We do not need to be punishing people through the criminal law,” said Robert Suttle, assistant director of the Sero Project, which advocates HIV criminalization law reforms. “This is a public health issue.”

Hunter, a hemophiliac, was diagnosed with HIV in 1981, at age 7. He said he and his family largely kept his status a secret.

“People were treated harshly who had this disease,” said Hunter. “They were treated like outcasts.”

But though the public’s perception of HIV has evolved, being on a sex offender registry carries a similar stigma. After he was released from prison in 2011, Hunter settled in Louisiana. He has found it difficult to find work, he said. Louisiana’s sex offender registry law requires him to register any address where he stays longer than seven days.

In the 1980s and 1990s, a flurry of HIV criminalization laws were enacted, many of which remain on the books. Today, 26 states have HIV-specific laws that criminalize exposure, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

HIV became “swept up” in the era’s “punishment fever,” explained Trevor Hoppe, author of “Punishing Disease: HIV and the Criminalization of Sickness.”

“Legislators around the country were already in the mode of punishment,” said Hoppe. “It was kind of a general approach they were taking to many social problems.”

Because there is no national database that tracks prosecutions, it is difficult to know how many people have been charged, convicted, or placed on the registry as a result of HIV criminalization laws, according to Catherine Hanssens, executive director of the Center for HIV Law and Policy. A comprehensive study of Florida’s criminalization laws found that more than 600 people had been arrested for an HIV-related offense between 1986 and 2017.

People with HIV are not out there passing HIV along in some intentional way.

Dorian-gray Alexander Louisiana Coalition on Criminalization and Health

Scientists, psychologists, healthcare providers, and HIV-positive advocates have condemned the laws over the decades since they were enacted, noting that there has been no association found between criminalization statutes and lower transmission rates.

“People with HIV are not out there passing HIV along in some intentional way,” said Dorian-gray Alexander, a member of the Louisiana Coalition on Criminalization and Health who is living with HIV. More than a third of the time, the transmission of HIV is between people who don’t know their status.

HIV criminalization statutes rarely take into account advances in treatment, condom use, or actual risk of transmission, according to advocates. For instance, in Arkansas, where Hunter was convicted, it is a felony to sexually penetrate another person without first disclosing one’s HIV-positive status. However, penetration is broadly defined as an “intrusion, however slight, of any part of a person’s body or of any object into a genital or anal opening of another person’s body.”

Cheryl Maples, an Arkansas attorney, plans to file a petition in federal court in the coming weeks that challenges the law’s constitutionality, she told The Appeal. Maples, whose uncle died of AIDS-related complications, has defended several people charged with HIV exposure. The state attorney general’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

“It is basically a crime that is against the LGBT community and other communities that are in disfavor,” said Maples. “People that are being charged with this are not predators.”

In Tennessee, sexual contact is not even required under the state’s aggravated prostitution statute. A person is in violation of the law if he or she knows they are HIV-positive and works “in a house of prostitution or loiters in a public place for the purpose of being hired to engage in sexual activity.” Those convicted are placed on the sex offender registry and face up to 15 years in prison.

People convicted of aggravated prostitution can petition to be removed from the registry if they were victims of sexual violence, domestic abuse, or human trafficking. Last year, then-Governor Bill Haslam signed into law a bill that allows those convicted as juveniles with aggravated prostitution to have their records expunged if they were victims of human trafficking.

It’s a pointless and dangerous and stigmatizing response to what is a public health issue.

Catherine Hanssens Center for HIV Law and Policy

But regardless of why or when someone engages in sex work, sex workers living with HIV need “services, not handcuffs,” said Alex Andrews, co-founder of Sex Workers Outreach Project (SWOP) Behind Bars.

“When you put someone on a registry for having HIV, that’s public information,” said Andrews. “Put sex work on top of that and you have a really bad situation for survival.”

The state’s aggravated prostitution statute and HIV exposure law are both felonies that require sex offender registration. That’s different from the way Tennessee law governs the disclosure of other infectious diseases. It is a misdemeanor to engage in “intimate contact” without disclosing a diagnosis of Hepatitis B or C, but failure to disclose those diseases does not require sex offender registration.

As attempts are made to reform HIV criminalization laws, advocates worry about changes that tie criminalization solely to a person’s risk of transmission. Doing so, they warn, could marginalize those without access to treatment and those with detectable viral loads. (Those with undetectable viral loads, like Hunter, have “effectively no risk” of transmitting the virus, according to the CDC.)

Repealing HIV-specific laws is often insufficient, they add, because people can still be exposed to harsh punishments. People in states without such laws have been charged with attempted murder or assault with a deadly weapon for a range of incidents including spitting. (HIV cannot be transmitted through saliva.)

Modernizing statutes should focus on a person’s intent, and conduct likely to cause harm, not a failure to disclose, said Hanssens, the HIV law and policy center executive director. Any reform must also cease placing people on the registry, a practice she called “irrational and unconscionable.”

“You cannot treat consensual sexual contact as a criminal wrong simply because that particular person happens to have one or another disease,” said Hanssens. “It’s a pointless and dangerous and stigmatizing response to what is a public health issue.”

Hunter has joined HIV-positive advocates from across the country in speaking out about the harms of criminalization and the sex offender registry in particular. He also works to reduce the persistent stigma and fear surrounding HIV by helping young people tell their families they are HIV-positive.

“They need to understand that it’s not a death sentence,” said Hunter. “I’m married. My wife is not HIV-positive, and we are trying to have a child.”

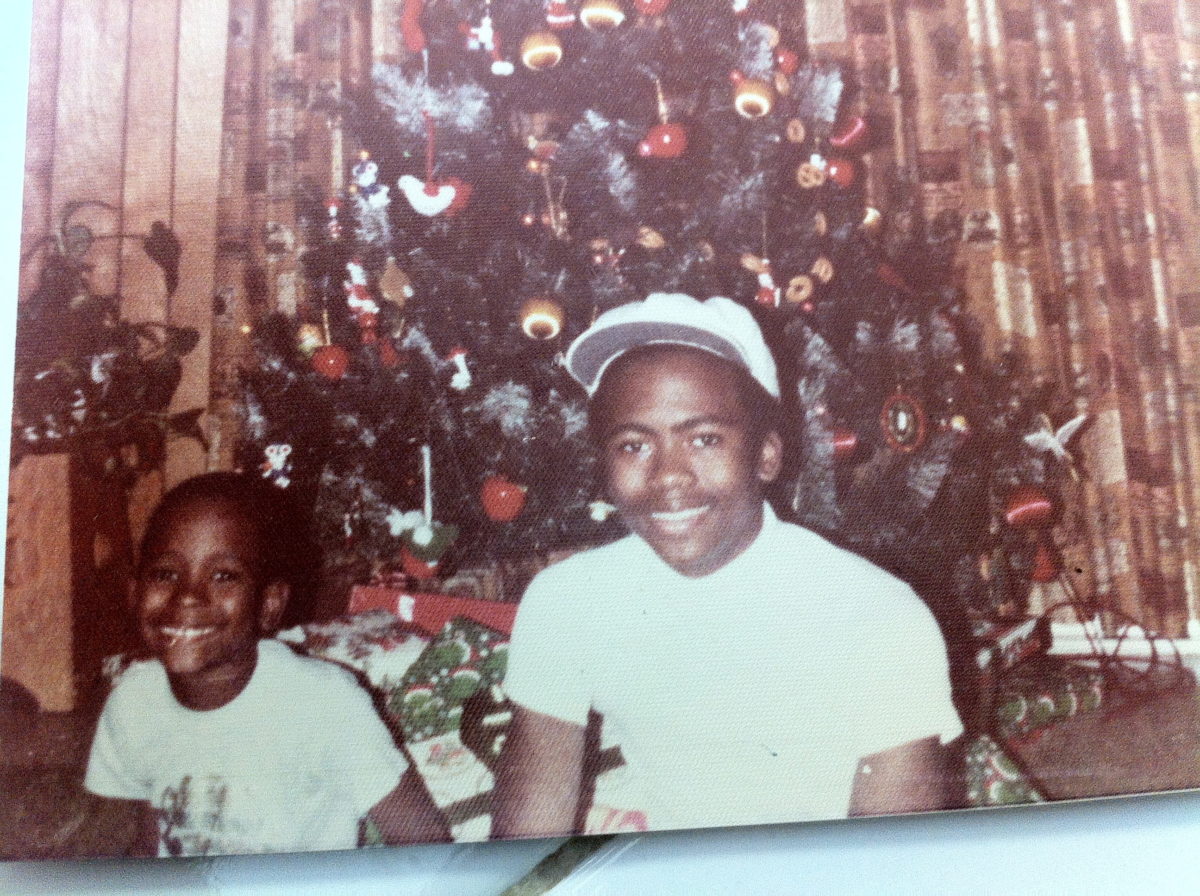

He has started a nonprofit organization dedicated to HIV and AIDS education in his brother’s name, the Dr. Michael A. Hunter Foundation. His brother, like Hunter, was a hemophiliac who contracted HIV from a blood transfusion. He died from AIDS-related complications in 1994.

“I’m Mark, and I happen to be HIV-positive,” said Hunter. “I had to embrace that, and once I embraced it, I let go of a lot of the pain.”