Texas’s First Death Sentence of 2018 Crystallizes the State’s Longstanding Capital Case Crisis

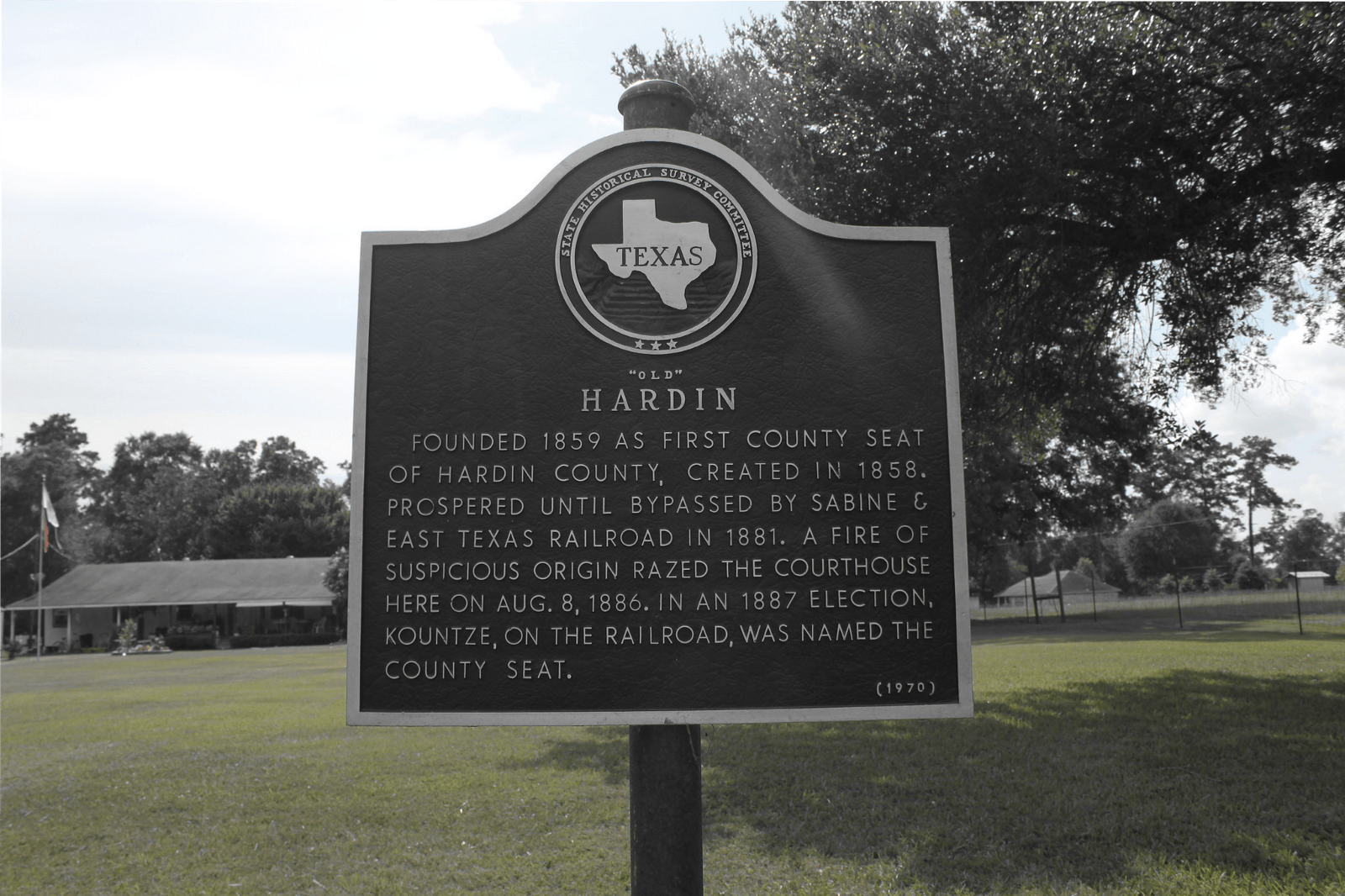

A Texas man tried and convicted in late February of murdering his girlfriend’s daughter is the state’s first death sentence in 2018 — but it also may be its latest example of prosecutorial misconduct in a capital case. On February 28, a jury in Hardin County, a small East Texas county near the Louisiana border, handed down a […]

A Texas man tried and convicted in late February of murdering his girlfriend’s daughter is the state’s first death sentence in 2018 — but it also may be its latest example of prosecutorial misconduct in a capital case.

On February 28, a jury in Hardin County, a small East Texas county near the Louisiana border, handed down a death sentence to 40-year-old Jason Wade Delacerda. According to Delacerda’s defense attorneys, it was the conclusion of a trial in which prosecutors attempted to hide exculpatory evidence, violated a rule barring witnesses from talking with other witnesses about the case, and played an emotional song from the hit 2012 movie Pitch Perfect in a bid to allude to evidence the judge had already ruled inadmissible.

Such allegations of misconduct in Texas are not limited to Delacerda’s case — in 2017, nearly half of the stays of execution granted in the state involved cases that “may have been tainted by false or unreliable evidence,” according to the website The Open File, which tracks prosecutorial misconduct.

“I’d say that this is a pervasive problem,” Amanda Marzullo, executive director of Texas Defender Service, a nonprofit working to improve the quality of representation afforded to those facing death sentences, told The Appeal. “This is in part because, in general, emotions run high in death penalty cases on both sides and prosecutors are particularly aggressive.”

Attorneys representing Delacerda — who faced a capital murder charge for the 2011 murder of his girlfriend’s four-year-old daughter, Breonna Loftin — claim that his trial was marred by multiple acts of prosecutorial misconduct.

One of Delacerda’s attorneys, Ryan Gertz, said that Hardin County District Attorney David Sheffield brought Delacerda’s two sons — who were set to testify against their father — into a room with their mother and her husband, who were potential witnesses, to confer with them about their testimony. Gertz said that this meeting represented a violation of Rule 614, which states that witnesses must not share their testimony with other witnesses.

Judge Steven Thomas did not formally acknowledge the Rule 614 violation, but prevented Delacerda’s sons from testifying in the guilt phase of the trial on the grounds that it included inadmissible character evidence. Thomas, however, allowed one of Delacerda’s sons, the son’s mother, and her husband to testify during the trial’s penalty phase, which led to another alleged act of misconduct. Gertz claimed that prosecutors failed to provide notice to the defense that the testimony of the stepfather of Delacerda’s sons would include alleged crimes that Delacerda had not been convicted of, allowing him to tell the jury about being punched in the face by the defendant in a parking lot.

Additionally, Gertz alleged that the state committed three Brady violations, meaning that it failed to disclose evidence that is favorable to the defense as required by law. In one instance, prosecutors allegedly failed to disclose that one of the investigators in the case was arrested for child pornography and lying to a postal inspector about having it shipped to him by mail.

And during his closing statement, Assistant District Attorney Bruce Hoffer made what Gertz said was an improper attempt to appeal to the jury’s sympathies by displaying a picture of Breonna while playing the song “Cups” from Pitch Perfect featuring the refrain “You’re gonna miss me when I’m gone.”Hoffer later told the media that the song choice was inspired by a statement Breonna allegedly made to her grandmother, “Will you miss me when I die?” weeks before her death that the judge had ruled inadmissible because it was considered hearsay.

“It was ridiculous,” Gertz said. “I’ve never had anybody so blantantly appeal to a jury’s emotions as that, the only thing that would’ve been worse than that song would’ve been ‘Wind Beneath My Wings.’”

The Hardin County district attorney’s office did not return a request for comment from The Appeal.

Claims of prosecutorial misconduct — including Brady violations, junk scienceand unreliable witnesses — in capital cases like Delacerda’s are commonplace in Texas.

In 2017, the execution of Paul David Storey — who was convicted in the 2006 murder of Jonas Cherry during a robbery of a mini golf course — was stayedafter his attorneys discovered that prosecutors lied to the jury about the victim’s family’s wishes to pursue the death penalty.

During Storey’s 2008 trial, prosecutors insisted that Cherry’s parents sought to have Storey executed, despite the fact that they had told the state that they didn’t believe in the death penalty. “As a result of Jonas’ death, we do not want to see another family having to suffer through losing a child and family member,” Glenn and Judith Cherry later wrote in a 2017 letter to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles, “due to our ethical and spiritual values we are opposed to the death penalty.”

Also in 2017, the execution of Kosoul Chanthakoummane, a man convicted and sentenced to death for the 2007 murder and robbery of a real estate agent in Collin County, Texas, was stayed after defense attorneys argued that the state had relied upon discredited forensic evidence, including bite marks. As of January of 2017, bite mark evidence has resulted in more than two dozen wrongful arrests and convictions.

Such cases demonstrate that even though executions are on the decline in Texas, the state remains a locus for misconduct in death penalty prosecutions.

Compounding the misconduct crisis is the fact that systemic issues in death penalty cases are less likely to be remedied in small counties like the one where Delacarda was tried. Redirecting limited public resources toward costly capital cases means that pressure on prosecutors to secure a death sentence is high, encouraging a do-whatever-it-takes-to-win approach.

“For the rural counties they’re going to decide, can we fix our broken drainage systems,” Jim Marcus, a University of Texas law professor specializing in capital punishment told The Appeal, “or put this guy on death row?”

But difficult, longstanding problems like capital case funding do not justify misconduct, Marcus added, noting that although it is often forgotten, prosecutors are supposed to be carrying out an important duty:

“The prosecutor’s ethical obligation is not to win at all costs, their role is to do justice.”