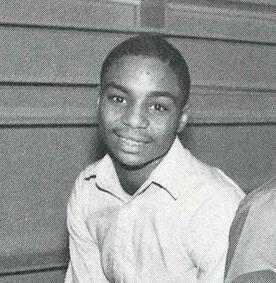

Terry Williams finally gets a chance

Of all the death row stories, perhaps none is quite as heart wrenching as that of Terry Williams, who was sentenced to death in Philadelphia three decades ago. This week, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has decided that Williams should finally get another penalty-phase trial, which means that Williams has a chance to explain why he deserves […]

Of all the death row stories, perhaps none is quite as heart wrenching as that of Terry Williams, who was sentenced to death in Philadelphia three decades ago. This week, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has decided that Williams should finally get another penalty-phase trial, which means that Williams has a chance to explain why he deserves the mercy that no one ever showed him during his short life outside of prison.

The young life of Terry Williams as a black boy in 1980s Philadelphia is horrific by any standard. He was the victim of relentless abuse since birth. His mother and stepfather beat him regularly with belts, switches, extension cords— anything. At 6, he was raped by an 11-year old friend who tricked him with cupcakes and cartoons. A year later, he was sexually abused again. After that, a teacher tried to earn Williams’s trust, only to begin sexually exploiting him as well. He was gang raped by boys at a juvenile detention facility. He then began having sex with older men (who baited him with money and food), who also beat him. His mental health deteriorated noticeably.

In 1986, 18-year-old Terry Williams was arrested and tried for two separate murders, both of older men who had taken advantage of him sexually. The first trial was for the death of 50-year-old Herbert Hamilton, whom 17-year-old Williams had stabbed and beaten to death. Hamilton was well-known in the neighborhood both for providing the local youth pills and for his penchant for sex with kids. In light of these mitigation circumstances, the jury found Williams guilty of third degree murder.

For the next trial, which involved the death of 50-something Amos Norwood, the Philadelphia prosecutor Andrea Foulkes, under the direction of then-DA Ronald Castille (who sent 45 people to death over his tenure), had a plan to ensure that Williams would be sent to death row. The facts of the case are fairly similar to the Hamilton trial. Norwood had sexually abused Williams during his teen years. A several months after the death of Hamilton, Williams met up with Norwood in a parking lot. Norwood pushed Williams against a car and began having sex with him as Williams begged him to stop. The next day, Williams and a friend beat Norwood to death.

During the Norwood trial, the jury never heard evidence of Williams’s horrific childhood nor his history of abuse nor his abuse at the hands of Norwood. The jury never heard that Norwood had been abusing Williams for five years. Instead, Foulkes portrayed him as “a kind man [who] offered him a ride home.” Williams had an incompetent defense attorney, who met him for the first time the day before jury selection, and a faulty mental health expert. He was sentenced to death.

In September 2012, just days before Williams’s scheduled execution, a judge took the extraordinary step and stayed the execution, ordering a new penalty-phase trial because Foulkes had concealed evidence of Williams’s abuse. There’s not really a debate that Foulkes knew about Williams’s troubled history. She had already tried him for another murder that same year. And, she know that Norwood had been abusing Williams throughout his teens — documents in the prosecution’s file in her handwriting prove this. Five jurorsalso verified that, had they known about the abuse, they would not have voted for death. The victim’s widow even wrote a letter saying that Williams should not be executed.

Former Philadelphia District Attorney Seth Williams refused to remove Williams from death row and vowed to fight the decision even though hundreds of thousands of people signed a petition and dozens of former prosecutors urged him to grant clemency. Williams showed very little mercy for a victim of abuse, saying publicly that he was “weary of this murderer’s effort to portray himself as a victim.” But, he was thwarted by Governor Tom Wolf, who stayed all Pennsylvania executions until a thorough evaluation of procedures to ensure fairness. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court agreed with Wolf. Williams was saved for the moment.

Terry Williams’s case was appealed all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reversed Williams’s death sentence in 2016 because Chief Justice Ronald Castille — a judge on Williams’s case — had also been Foulkes’s boss when she prosecuted Terry Williams. Since then, Seth Williams has been forced to resign as District Attorney of Philadelphia and pled guilty to criminal charges for corruption. Terry Williams’s case is unresolved.

So, what should we take away from this case? It’s a win for Terry Williams, so far as anything involving his case can be perceived that way. More than that, however, it’s a tale of how far prosecutors will go to protect their past decisions as well as how no one was ever found accountable for the injustices in Terry Williams’s trial. Castille was the Chief Justice on Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court until he retired honorably in 2014. Andrea Foulkes now prosecutes for the U.S. Attorney’s Office. If the death penalty is reserved for the most heinous crimes, what can then justify defending it in the case of Terry Williams? This is just further evidence that capital punishment doesn’t make sense.

Larry Krasner, the incoming Democratic nominee for District Attorney, has publicly promised never to seek the death penalty. He will follow in a growing tradition of prosecutors who hope to learn from the mistakes of their predecessors. But it’s hard to see how any change can ever compensate for the young man that could have been Terry Williams.