A Jury Found Them Not Guilty of Killing a Cop. A Judge Sentenced Them to Life Anyway.

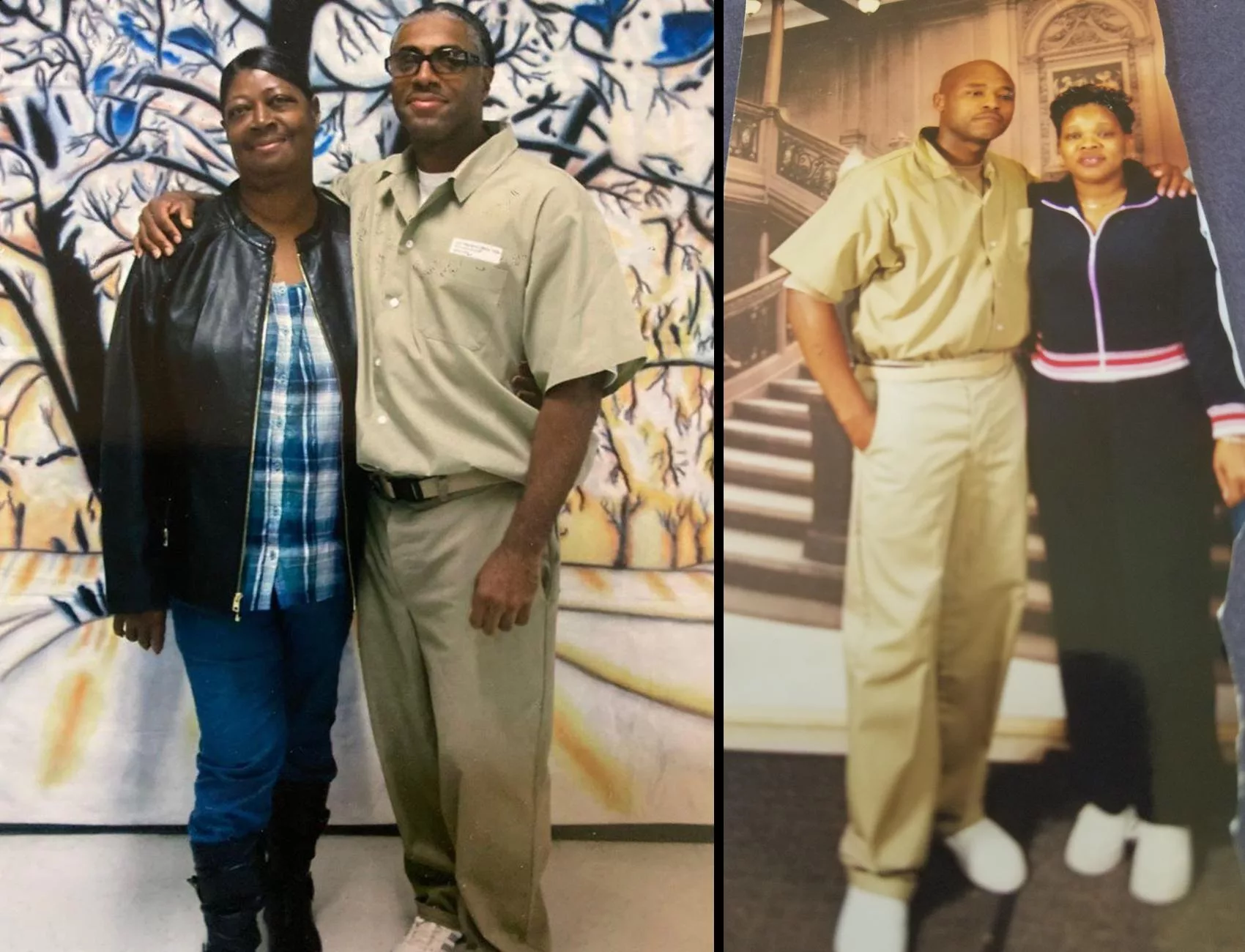

Terence Richardson and Ferrone Claiborne have spent decades behind bars even after a jury acquitted them of murder. Now, the Virginia Supreme Court is set to decide their fate.

More than two decades ago, a jury found Terence Richardson and Ferrone Claiborne not guilty of murdering a police officer. But a judge disagreed, and unilaterally sentenced them to life in prison. After 22 years behind bars, their case is now in the hands of Virginia’s highest court, which will decide whether to allow the men to admit new evidence they say proves their innocence.

In 1998, Waverly police officer Allen Gibson was shot and killed with his own gun in the woods behind an apartment complex in the small town of less than 2,500 people. Evette Newby, who lived in the apartment complex facing the woods, told police she’d seen three men go into the woods. Then, she said, she saw two of them struggling with Gibson and heard a loud pop. She identified two of the men as Richardson and Claiborne. Newby also identified another man at the scene, but police told her it was impossible for that man to have been present because he was incarcerated. Newby later said law enforcement officials pressured her to say she saw Richardson shoot Gibson, which she would not agree to, and gave her small amounts of money.

There was no physical evidence linking Richardson and Claiborne to the crime, but they emerged as the primary suspects in the ensuing investigation, despite the fact that police had evidence suggesting another man may have been involved: Leonard Newby, the witness’ brother. An attorney currently representing Richardson and Claiborne says the defense never knew police had evidence pointing to another suspect.

Richardson and Claiborne insisted they had nothing to do with Gibson’s death. But their attorneys at the time told them that they could be sentenced to death if they went to trial and lost. Richardson and Claiborne were poor Black men accused of killing a white police officer in the South. Out of fear for their lives, they took guilty pleas.

“He said if you go to trial and you mess around and you lose, you could get the death penalty,” Richardson told local news.

Richardson pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter and was sentenced to ten years in state prison with five years suspended. Claiborne pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge, as an accessory to Richardson’s crime. The county attorney at the time, David Chappell, said he made those plea bargains with Richardson and Claiborne because the case was too compromised: One of the first officers to arrive on the scene was Waverly Police Chief Warren Sturrup, who picked up Gibson’s gun with his bare hands and, in doing so, tainted any fingerprints that may have been on the gun.

Gibson’s family was outraged by what they saw as a lenient sentence for Richardson and Claiborne, who, in their view, had pleaded guilty to being involved in Gibson’s death. Following public outcry, federal prosecutors brought additional charges against the pair accusing them of selling crack cocaine and murdering a police officer during a drug deal gone wrong.

In 2001, Richardson and Claiborne went to trial. A jury found them not guilty of officer Gibson’s murder, but guilty of selling crack.

But in an unusual move, District Judge Robert E. Payne sentenced Richardson and Claiborne to life in prison using “acquitted conduct sentencing,” a legal mechanism approved by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1996. In that case, known as Watts, the court ruled that a jury’s acquittal does not prevent a judge from using the conduct the defendant was acquitted of against them when sentencing them for another charge.

“The Court’s decision to sentence Terence and Ferrone to life in prison despite being found not guilty robbed due process of its very meaning,” said Jarrett Adams, Richardson and Claiborne’s attorney and co-founder of Life After Justice. “The U.S. Supreme Court must do away with its ruling in U.S. v Watts, which gives a judge the discretion to make a jury’s finding meaningless, and prevent further miscarriages of justice from occurring like the one we see in this case.”

Adams has spent years fighting for Richardson and Claiborne’s freedom. Soon after taking on the case in 2018, Adams uncovered several pieces of potentially exculpatory evidence that police had never previously shared.

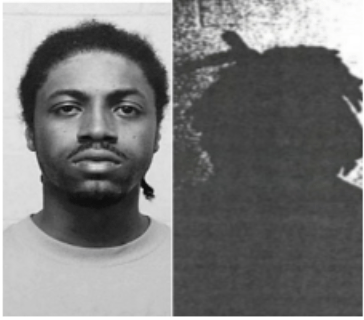

Before Gibson died from his injuries, he described his attackers to a state trooper. He said that one man was tall and thin with hair that would resemble dreadlocks pulled back into a ponytail. The other was shorter and squatter with no hair or sparse hair. The man with dreadlocks was the one who wrestled for his gun, Gibson said. It went off during the struggle and sent a bullet into Gibson’s stomach.

Neither Richardson nor Claiborne had dreadlocks. At the time of the murder, Richardson had cornrows with braids that hung down the back of his neck. Claiborne was bald, but he was tall and thin, around 6 feet. Richardson, meanwhile, was several inches shorter than officer Gibson. Physical evidence recovered from the scene did not link Clairborne or Richardson to Gibson: DNA found on Gibson’s shirt did not match the DNA found on Richardson’s shirt, and Richardson, Claiborne, and Gibson were all eliminated as possible contributors to the hair fragments found on each other’s clothing.

A young witness who police repeatedly interviewed said the man she saw in the woods with Gibson had dreadlocks—though at other times she said the man had cornrows. Shannequia Gay was nine or 10 at the time of the shooting, and was playing outside with her cousin that morning when she saw a police car stop outside the apartment complex. According to a statement Gay made just hours after the incident, she saw Gibson get out of his police car, unholster his gun, and walk into the woods.

The trees obscured her view, but she heard a loud noise that scared her. She walked closer to the woods to get a better look. There she saw Gibson lying on the ground—and “the man with the ‘dreads’” running out of the woods.

Police showed Gay photos of possible suspects. According to a federal prosecutor, Gay became scared when she saw Leonard Newby’s photo and later picked him out of a photo lineup. This information was unknown to Richardson and Claiborne’s defense attorneys.

A few days after Gibson’s murder, someone left an anonymous tip on the Virginia State Police Department’s answering machine. The caller alleged that Leonard Newby had been involved in the murder, then cut his dreadlocks.

Based on this evidence, Adams filed a petition for a writ of actual innocence with the Virginia Court of Appeals in 2021, seeking to vacate Richardson’s conviction. That same year, then-Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring’s conviction integrity unit carried out an investigation into Richardson’s case and determined that he should be granted a writ of innocence.

In a motion filed in the Court of Appeals, Herring wrote that it was “clear from the record that some information and evidence presented in Mr. Richardson’s federal trial was unavailable to him when he pled guilty in state court, including information that a key witness lied to state investigators and lied during the preliminary hearing.” (Claiborne cannot file a writ of innocence Richardson because he pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor, not a felony, but if Richardon’s state conviction is overturned, it would also help Claiborne.)

According to Herring’s investigation, Gay’s description of the assailant as a man with dreads, the photo lineup identifying a different suspect, and the 911 call also alleging Newby’s involvement were all unknown or unavailable to Richardson’s defense counsel. As such, Herring concluded, Richardson should be granted a writ of innocence because “no rational trier of fact would have found Mr. Richardson guilty if that evidence was presented.”

But in January 2022, a new state attorney general took office. Within a month, Jason Miyares, a Republican who had campaigned on a “tough-on-crime” platform, reversed course and filed a pleading opposing Richardson’s writ of innocence.

In June 2022, the Virginia Court of Appeals dismissed Richardson’s innocence petition, alleging that Richardson was not entitled to a writ of innocence because his prior attorneys failed to do their due diligence to uncover the exculpatory evidence police and prosecutors did not turn over. Richardson appealed. On November 2, Adams and the attorney general’s office made their cases before the Virginia State Supreme Court.

Miyares’ office argued that Richardson is not entitled to a writ of innocence because he has not proved that this evidence is new or material and Richardson’s prior attorneys could have uncovered the missing evidence if they had been more diligent.

Adams contended that no amount of due diligence could have uncovered evidence that law enforcement willfully concealed. Further, Adams argued, even if Richardson’s prior attorneys had been able to interview Gay, the child was not the one in possession of the photo lineup or her statement, nor was she in possession of the 911 call. Adams is asking the court to order an evidentiary hearing to clear up the inconsistencies in the record.

“The federal jury found Mr. Richardson and Mr. Claiborne not guilty,” Adams said. “This case deserves closure. That only happens if this court acts in order to an evidentiary hearing to both the appellate court and this Court could have a clear record to decide on whether Mr. Richardson and Mr. Clairborne ought to spend the rest of their lives in prison.”

The court will likely issue a ruling sometime in the next several months.

Editor’s Note: Richardson spells his first name with one “r,” but many of the court records in his case use two. We have updated the story to reflect the correct spelling of his name.