Sex Registries as Modern-Day Witch Pyres: Why Criminal Justice Reform Advocates Need to Address the Treatment of People on the Sex Offender Registry

Perhaps the most irrefutable statement that can be made about modern day America is this: we have a penchant for putting people in cages. More than any other nation on the planet, we rely on incarceration as the fix for our social ills. America’s unprecedented prison boom spawned advocates who work tirelessly to put the police state […]

Perhaps the most irrefutable statement that can be made about modern day America is this: we have a penchant for putting people in cages. More than any other nation on the planet, we rely on incarceration as the fix for our social ills.

America’s unprecedented prison boom spawned advocates who work tirelessly to put the police state toothpaste back into the tube. As a result, despite a steady media diet of cops and robbers police procedurals, the rhetoric on crime policy has begun to shift. The country appears to be approaching something akin to apostasy. We have begun to lose our faith in imprisonment as an effective response to problems like drug addiction. For the first time since the data was tracked, state and federal prison populations declined in 2014, albeit slightly, from historic highs.

Yet amidst this wave of reform, one group of people continue to languish in the collective “harsher is better” mindset: sex offenders.

The American journalist H.L. Mencken once said that

The trouble with fighting for human freedom is that one spends most of one’s time defending scoundrels. For it is against scoundrels that oppressive laws are first aimed, and oppression must be stopped at the beginning if it is to be stopped at all.

Mencken was right: if you’re interested in defending human freedom, get ready to spend a great deal of time defending people you might not like. The guns of oppression are aimed at the friendless before they swing to the connected and moneyed.

And no one is more friendless than those on the sex offender registry.

The sex offender is the modern-day witch: the registry, the contemporary pyre. A scarlet letter for our technocratic era, forcing people to register as sex offenders “is what puritan judges would’ve done to Hester Prynne had laptops been available.” While undoubtedly there are those on the registry who have been convicted of blood curdling crimes, the designation is also extended to those who have been convicted of far more banal ones.

Reformers urgently need to draw public attention to the cruel and unnecessarily harsh treatment afforded to sex offenders within the justice system. Sex offender registries are rapidly proliferating and becoming an increasingly popular back-end tool for feeding people into the carceral state.

In understanding the reasons why sex offenders ought to be a higher priority for mainstream justice reform advocates, a grasp of the evolution and operation of the sex offender registry is critical.

The forebears for modern sex offender registries and so-called “sexual psychopath laws” first appeared in late 1930s California, and largely targeted LGBTQ individuals. What began as relatively simple lists of individuals convicted of crimes grew in the wake of two high profile murders of children in 1937, which spawned a moral-sexual panic: simultaneously horrifying and captivating the nation.

Operating on the premise that the American public had a right to know about the sordid pasts of those it deemed miscreants, registries began to spread from state to state, city to city, arguably arriving in modern form in the wake of the grisly rape and murder of Megan Kanka in New Jersey in 1994 — the namesake for Megan’s Law (the colloquial term by which sex offender registries are most commonly known).

Perhaps owing to our puritan roots, it has been said that everyone in America lies about sex, because everyone lies about the designs that they have on their neighbors’ bodies.

Our institutions may not be terribly different.

In 2003, in a case titled Smith v. Doe, the United States Supreme Court was asked to consider whether the Alaskan sex offender registry was so punitive as to be constrained by the ex post facto clause of the United States Constitution, which is meant to stop punishments from being increased after the fact. In asserting — falsely, as has been conclusively demonstrated — that the risk of re-offense posed by sex offenders was “frightening and high,” the Court green-lit a cross-country, decade-long race to the bottom in denying those on the registry essential and time-honored legal protections.

Despite having been given two recent high-profile opportunities to revisit its holding and erroneous factual assertions, the Supreme Court has so far chosen not to do so. Worse, in the concurring opinion in 2017’s Packingham v. North Carolina, the conservative wing of the Court reaffirmed Smith’s central fallacy, which laid the foundation for present-day sex offender registries. Justice Anthony Kennedy, who authored the majority opinion in both Smithand Packingham, remained silent on the elephant in the room that was given life by his authorship in Smith: the erroneous assertion on re-offense rates.

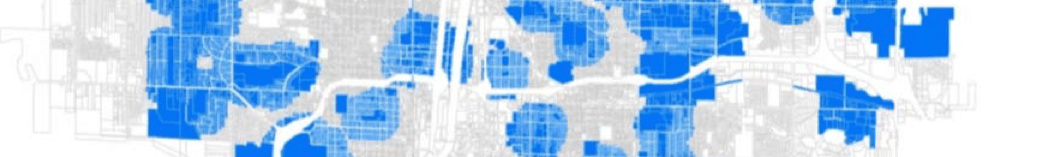

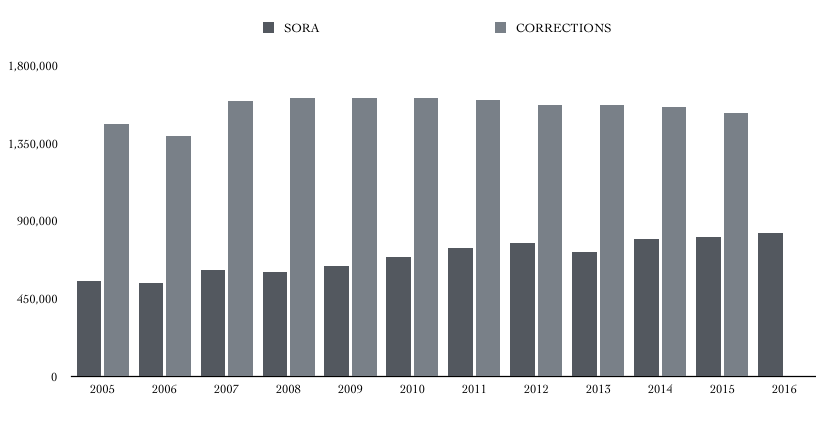

In the wake of Smith, sex offender registries and their attendant restrictions have grown at a brisk clip. The number of people listed on a sex offender registry in the United States has grown from slightly more than 500,000 in 2005 to 874,725 today. Research has found that sex offender registries have a disproportionate impact on minorities.

While registries and their attendant requirements are sold as enhancing public safety, research consistently indicates that they are exceedingly bad at this goal. One explanation is because, contrary to Smith’s baseless assertion and what most believe, people on the registry have one of the lowest rates of re-offending out of any class of criminal.

A tenuous relationship with facts notwithstanding, registries are wildly popular: a whopping 94% of Americans support their existence and increasingly harsh treatment of those required to register (though most people report that they never actually check the registry). Even as the public appears to be finally questioning the wisdom of putting so many people in cages, the same cannot be said for its seeming willingness to put so many in virtual cages out of fear of what they “might” do.

Because of its popularity, public officials who depend on votes for their livelihood — like lawmakers and judges — are loathe to tinker with the registry, other than to devise ever-more severe punishments for its inhabitants.

As a piece of criminal justice machinery brought to bear on people, the registry can best be thought of as a two-headed beast: a 1–2 punch of distinct effects.

The first head is the direct impact on the lives of those on the registry itself. With no Due Process or Ex Post Facto brakes to slow down the juggernaut, it has become weaponized. A far cry from its origins as a simple list of purported perverts, it has morphed into a web of prison-without-bars that would make Franz Kafka blush. The oppressiveness, breadth, and lack of due process inherent in these modern day sex offender registries led a federal court in Colorado to label it a cruel and unusual punishment; a legal conclusion virtually unheard of outside of the cloistered world of death penalty litigation.

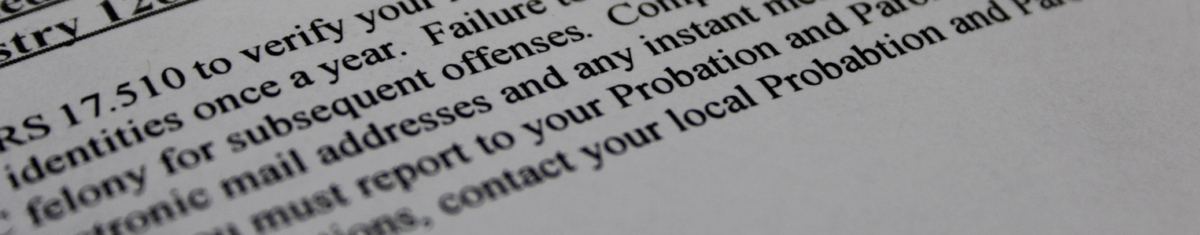

The second head is the tangle of legal requirements for those on the list: a knot of vague, illogical, ever-expanding, and sometimes contradictory laws that even lawyers, judges, and law enforcement have difficulty interpreting.Examples can include strict time limits on reporting even minor changes in information (such as online accounts) or residence, residency restrictions, or even the clothing one wears. States promise swift felony prosecutions if individuals do not observe hyper-technical compliance with these requirements.

Unsurprisingly, it is exceedingly easy to run afoul of the requirements, keeping those that do trapped in a cycle of legislatively-crafted “crime” that can be tantamount to a de facto life sentence. “Failure to register” is fast becoming the crime of choice for returning those on the registry to prison. In 2008 in Minnesota, failure to register charges became the most common reason sex offenders were returned to prison. Between 2000 to 2016, Texas saw a more than 700% increase in FTR arrests, from 252 in 2005 to 1,497 in 2017. To borrow a phrase from computer programming, this is not some kind of criminal justice bug.

It is a feature.

If America has a civil death penalty, putting people on the sex offender registry is it. In a recent experiment, when individuals were given the choice between being labeled a child molester or dying, most chose death.

The numbers of those currently on the registry are staggering, and continue to increase each year. Absent seismic shifts in criminal justice policy, the trend will likely continue. In a nod to Mencken’s admonition, the model popularized with sex offender registries is quietly being exported to other classes of crime — including white collar crimes, meth, guns, and animal abuse — despite little evidence that such registries accomplish much beyond branding its inhabitants irredeemable.

Decades on, ghosts of dead children are dragooned into supporting legislation that vastly expands the powers of the state, with few prepared to offer informed criticism. Despite doing little to protect children from the varied and pernicious harms that they face, sexual or otherwise, such “first-name” legislation is crafted by political operatives who use the memory of innocents in the same way one might use a human shield. No one with a beating heart is unmoved by the plight of parents of a murdered child; nor could one could easily criticize a law named in memoriam without simultaneously disrespecting that plight. Optics such as these are not accidental, they are political.

In order to sell policies to the public, our political leaders have often created boogeymen. During the heyday of the drug war, the boogeymen pressed into service were so-called superpredators, a heavily racialized term describing young people with “no respect for human life and no sense of the future.”Ostensibly toting Glocks and selling death to our communities, they ended up selling the belief in prison-as-protection, government-as-protector: a profoundly punitive turn in our legislation and discourse.

Even as we find ourselves in a new era marked by bipartisan acknowledgement of the need for criminal justice reform, in some areas we continue to be influenced by this same appeal to boogeymen, even if their shape and form changes. Instead of “super” predators, we’re now faced with “sexually violent” ones.

As with witches, the modern-day sex offender is largely a creature of our own creation, acting as a sort of repository for many of our collective moral anxieties around sex. While a baked-in ick factor often turns many erstwhile warriors into silent observers, awareness and informed response is badly needed from those within the criminal justice community.

And it is needed soon.