How decriminalizing sex work became a campaign issue in 2018

State Senate candidate Julia Salazar explains how sex workers’ rights is a key part of reforming criminal justice in New York.

“What is sex work?”

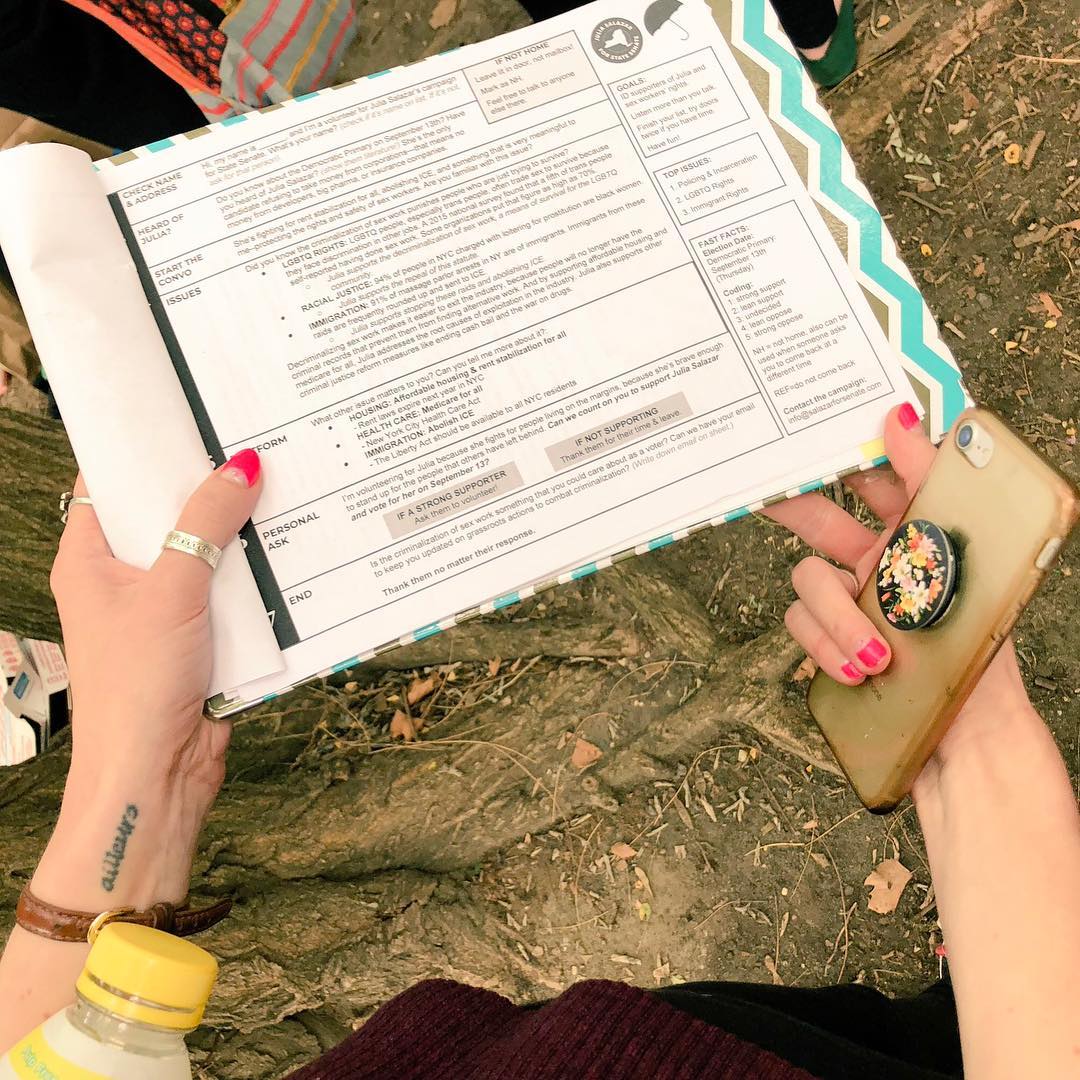

That was the question sex worker rights activists were expecting to hear often as they canvassed Brooklyn voters one drizzly August Sunday. At a gathering of about two dozen canvassers in a Williamsburg park, after the pizza and before knocking on doors, the activists circled under some trees to talk through how to answer that question. It was the first time this group had canvassed voters on sex workers’ rights, to talk with voters about the enforcement of prostitution laws, like anti-loitering policing that targets women of color and raids on massage businesses predominantly staffed by immigrants. It was the first time these activists had a candidate they could canvass on these issues for.

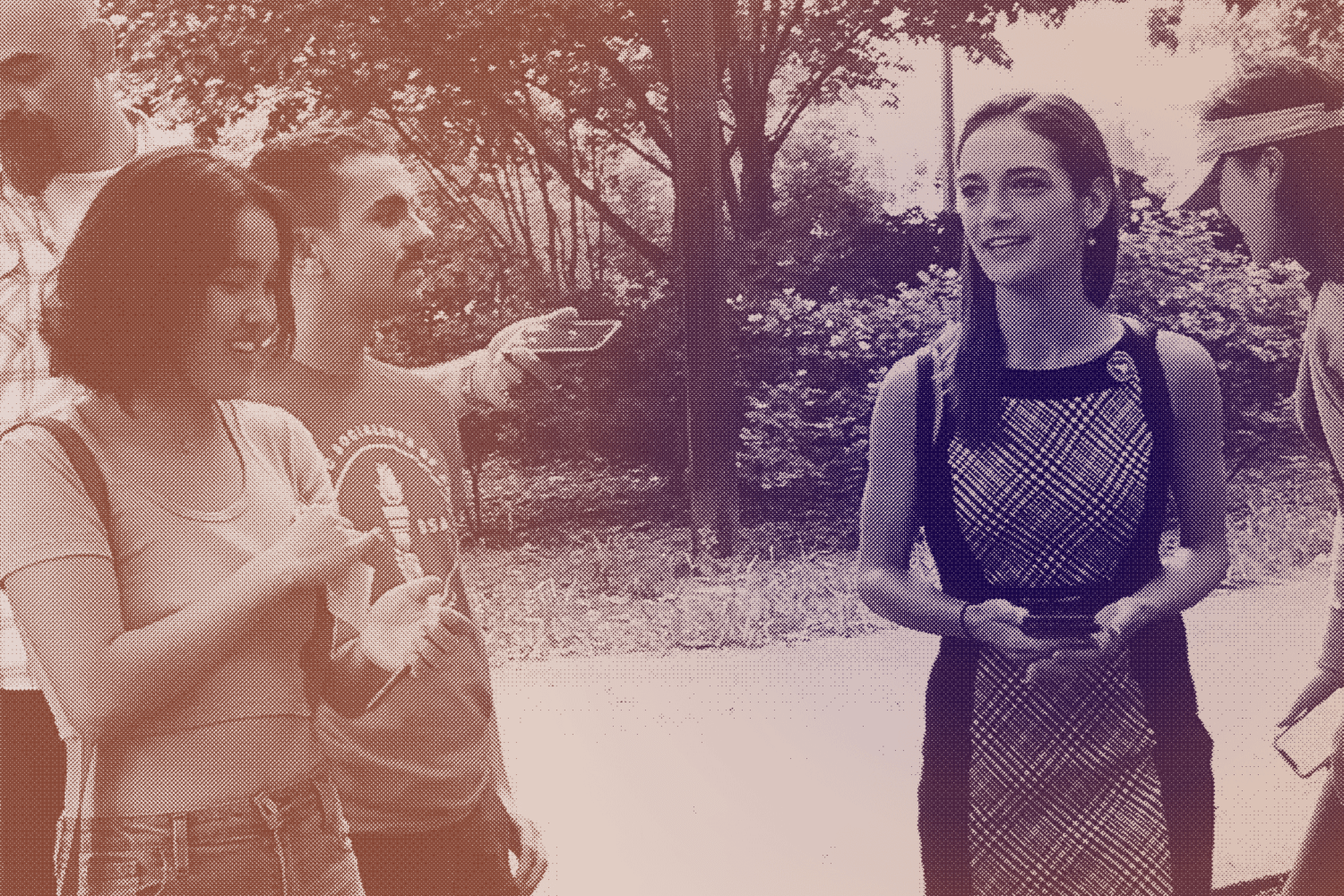

Julia Salazar, who is running for a New York state Senate seat representing north Brooklyn, arrived a few minutes later to send them off. She said sex workers—“my constituents”—are disproportionately criminalized in her district. Bushwick, for example, was among the top five New York City neighborhoods where police made “loitering for prostitution” arrests as of 2015. She referenced the Brooklyn courts, where 94 percent of those facing loitering for prostitution charges were Black. “That should disturb all of us,” she said.

Salazar argued that sex work policing was a central part of a bigger problem with Brooklyn’s approach to criminal justice. “Criminalizing sex work is a form of broken windows policing,” she said. “We shouldn’t tolerate it when it is used against sex workers.” If police gave out tickets for prostitution-related offenses instead of arresting people, she said, “this would actually go a long way in New York state toward decriminalization—toward full decriminalization.”

But how would she turn campaign promises into actual decriminalization? As Salazar explained in an interview with The Appeal, it will require identifying the issues where there’s a clear legislative path. She also plans to use her role and relationship to the movement to do “comprehensive political education” on sex work—like through Sunday’s canvass. Speaking “boldly and unapologetically” about sex workers’ rights helps destigmatize the issue, Salazar told The Appeal. “I think that is the most powerful work, and also it is the only way that ultimately we achieve legislative solutions as well.” Her campaign has provided a platform for sex workers to do some of that educational work, while offering a template for how the decriminalization fight could play out in other cities and states.

Salazar’s candidacy has been billed as part of a wave of young candidates on the left, many who have unseated veteran incumbent Democrats in their primaries. Her campaign has also generated intense scrutiny, with multiple news articles on her personal religious background, her political evolution, and most recently, allegations that in 2010 she stole from Mets player Keith Hernandez’s wife at the time. Police did not move forward with those charges, and Salazar received a settlement in a defamation lawsuit.

In its story on the allegations, the Daily Mail called Salazar a “socialist pin-up”. Salazar told The Appeal, “It’s sexist and repulsive for any reporter to call a woman running for office a ‘pin-up.’ They should also be ashamed for seeking to smear me when they can see that I was clearly viciously targeted by someone—and that I was given a settlement to resolve it.”

Her support for sex workers’ rights is unusual for a person running for office, though if 2018’s elections are any indication, that is starting to change rapidly. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who defeated longtime incumbent Representative Joseph Crowley of New York in her primary fight and is expected to head to Washington in January, says she opposes SESTA/FOSTA, new federal legislation that has pushed sex workers offline and made sex work more dangerous. When Suraj Patel was running for Congress against New York Representative Carolyn Maloney, a SESTA/FOSTA co-sponsor, he held a town hall meeting on sex work run by sex worker rights activists. Patel, who lost the primary, stopped short of supporting the full decriminalization of sex work. Still, the critical races to watch—when it comes to removing anti-prostitution laws from the books—will be state and local level races like Salazar’s.

Federal legislation like SESTA/FOSTA is harmful, but state and municipal laws against prostitution have threatened sex workers for far longer. These are the laws Salazar focuses on in her platform, and if elected, these are laws she could help change. A bill to repeal New York’s “loitering for prostitution” law has already been introduced. Likewise, lawmakers in Albany could repeal the prostitution exemption in the state’s rape shield law, another Salazar priority; this would bar sex workers’ past charges and convictions from being considered evidence in a rape case. The state could also prohibit allowing the possession of condoms as evidence in prostitution cases through another bill that has already been introduced (though in the past, the NYPD has opposed it). Some of the changes Salazar and sex workers seek, though, don’t require action in Albany. Prosecutors could simply opt not to pursue prostitution-related charges. Police could be instructed to stop making such arrests.

Sex workers have already been pushing these changes in New York, challenging the loitering law and fighting to end condoms-as-evidence, and Salazar is quick to underscore that in taking up these issues, she is following people who have been “fighting for a long time.” The current wave of criminal justice reform around sex work grew from a nationwide movement of sex worker rights activists older than most of the activists on the Salazar canvass. One of those early activists, Margo St. James, emerged as a pro-decriminalization force in the 1970s. After a prostitution arrest, she went to law school and appealed her conviction. St. James later ran for a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1996. The city’s district attorney endorsed her, though she lost.

What differentiates this moment from earlier waves of sex worker rights organizing is that it’s finding support from multiple candidates in simultaneous races before they make it into office. Salazar told The Appeal that she was approached by sex worker rights activists like Lola Balcon, an organizer who helped lead Survivors Against SESTA, and a member of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), who Salazar knew from DSA’s Socialist Feminist Working Group. “I would say it didn’t require a lot of consideration,” she said, when it came to backing sex workers’ rights.

Salazar said her policy positions also draw from her four years as a domestic worker, caring for two kids on the Upper West Side and cleaning apartments to supplement that income, and as an activist on a campaign to pass a New York state Domestic Workers Bill of Rights. “Getting involved with the Caring Majority campaign, it became apparent to me that domestic workers really are uniquely mistreated. They are excluded from collective bargaining rights—at least as an industry—are excluded from the conversation most of the time about labor rights and about workers’ rights, and that exclusion is really rooted in both misogyny and a history of slavery,” she told The Appeal. Sex workers, she said, “face similar challenges, of being not, still, conventionally thought of as workers, and having their labor deeply undervalued, and even scorned.” Sex workers, like domestic workers, she said, need to be recognized by and protected under the law.

Sex workers’ key difference from domestic workers, however, is that so many sex workers are criminalized. Sex workers’ labor rights issues are also criminal justice issues.

Salazar believes that the way forward is to tackle both kinds of issues together, and to do so, that will require getting the labor movement to see that criminal justice reform is “directly related to the mission of the labor movement as a whole and of labor unions.” Organized workers, community leaders, and elected officials, she said, “have a responsibility to demand that our labor movement institutions are focusing more on criminal system justice and reform as a whole and making the connection to workers rights.”

Sex workers are already working on making these connections, including while on the doorsteps of strangers. Eve, an escort and member of the DSA, told The Appeal that she had also knocked on doors for Ocasio-Cortez. If sex workers’ rights are having a coming-out moment in electoral politics, Salazar said that’s due to these workers and their organizing. This moment, she said, “it really is the result of long suffering relentless determination and building this movement. It’s really cool to finally see the fruits of that.”

And New York voters may finally be ready to listen. That Sunday with Salazar’s sex worker rights supporters, Eve bounded up six and seven flights of stairs with ease, in tenement walk-ups and doorman buildings. Her pitch was consistent, running quickly through Salazar’s support for affordable housing, abolishing ICE, and decriminalizing sex work. One voter, in a new building where few answered Eve’s knocks, did have some questions about what it would mean to abolish ICE. Another asked if she was his Uber driver. But none of the voters on the other side of those doors turned Eve away or even questioned her when she said she was a sex worker and that’s why she supported Salazar.