Anti-Online Trafficking Bills Advance in Congress, Despite Opposition from Survivors Themselves

This week, the Senate is expected to vote on a bill that could shutter websites that host sex-for-sale ads. The bill, known as SESTA — the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act — has been described by its supporters as a way to provide justice to victims of human trafficking by making it easier for them to file civil suits against the sites. However, a growing coalition of survivors of trafficking, sex workers, and women’s and LGBT rights groups oppose SESTA, saying it will endanger those it is meant to help.

This week, the Senate is expected to vote on a bill that could shutter websites that host sex-for-sale ads. The bill, known as SESTA — the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act — has been described by its supporters as a way to provide justice to victims of human trafficking by making it easier for them to file civil suits against the sites. However, a growing coalition of survivors of trafficking, sex workers, and women’s and LGBT rights groups oppose SESTA, saying it will endanger those it is meant to help.

SESTA’s companion bill passed the House of Representatives last week, racking up 388 votes in favor, with 25 opposing votes from both Democrats and Republicans. The House bill, the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (or FOSTA), would give state attorneys general the power to bring criminal prosecutions against people who operate websites “with the intent to promote or facilitate the prostitution of another person.” As FOSTA’s original sponsor Rep. Ann Wagner (R-MO) described the bill during a floor speech, it would “put those bad actor websites behind bars.”

SESTA, the Senate bill, is currently supported by a seemingly disparate coalition: anti-sex work groups, some anti-trafficking services, religious right groups, and some women’s rights groups. Though they originally opposed it on the grounds that it would compromise free speech online, most major tech companies now back SESTA. The bill has also won a personal endorsement from Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg.

Should FOSTA and SESTA become law, anyone engaged in the sex trade — whether through choice, circumstance, or coercion — risks losing access to websites like Backpage and others that connect them to work. Advocates say this would be a direct attack on sex workers’ ability to continue doing sex work on their own terms, and risk making people in the sex trades more vulnerable to trafficking.

Empowering Prosecutors, Eradicating the Sex Trade

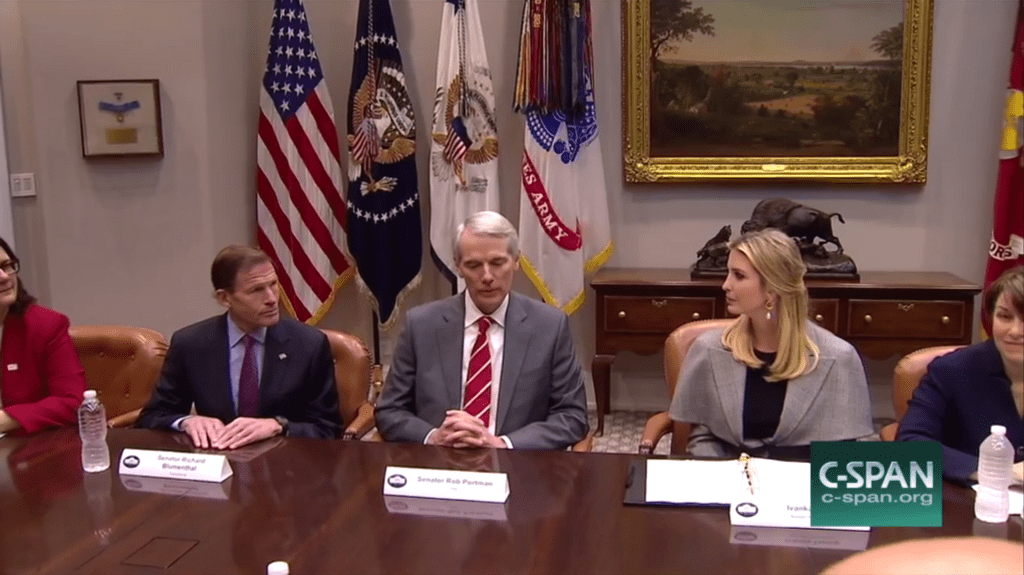

FOSTA and SESTA are significant not only for what conduct they seek to outlaw, but for whose power they extend. Though FOSTA expands the Mann Act, criminalizing the act of “facilitating” prostitution online, using and operating a website to “facilitate” prostitution is already a federal crime under the Travel Act (with which the popular men’s escort site rentboy.com was prosecuted). But FOSTA goes much further — it hands the power to prosecute website operators to state attorneys general. State AGs have long demanded action against online ads for sexual services. In 2008, then-Connecticut Attorney General Richard Blumenthal led an effort by 40 state AGs against Craigslist over its Adult Services section. Blumenthal, a Democratic senator, introduced SESTA along with Sen. Rob Portman (R-OH) in 2017.

Supporters of the legislation say that by permitting legal action by or on behalf of those who were advertised on such websites, it will make websites themselves liable for trafficking. One lobbying group urged people to spread the message, “People are not products. Stop selling them online.” Another was more blunt: “Stop internet companies from enabling child rape.”

Driving such messages are groups who have long lobbied the U.S. government to further criminalize the sex trade, including those behind the new organization World Without Exploitation (WWE), helmed by former Brooklyn prosecutor Lauren Hersh. That group was founded in part by the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW), which has organized women’s rights activists as far back as the Clinton administration not just against trafficking, but to press governments to define all commercial sex as trafficking. CATW sees sex workers’ rights advocates — and their prominent allies, like Amnesty International, as its opposition; in fact, CATW will not use the term “sex work.”

“The truth is that what we call sex trafficking is nothing more or less than globalized prostitution,” CATW co-director Dorchen Leidholdt — now head of legal services at Sanctuary for Families, another WWE co-founder — remarkedat an anti-“demand” conference in 2003. “What most people refer to as ‘prostitution,’” Leidholdt added, “is usually domestic trafficking.” For these groups, SESTA is another step in a decades-long fight against sex work that hinges on explicitly collapsing any legal difference between sex work and trafficking. WWE founding co-chair Anne K. Ream describes SESTA as a law that “will strike a blow to those who buy and sell other human beings.” In a January Senate briefing, WWE’s talking points on SESTA said what they really wanted was an end to the “global sex trade.”

Along with lobby groups like WWE, an anti-Backpage documentary I Am Jane Doe also helped create demand for SESTA and FOSTA. Original SESTA co-sponsor Sen. Rob Portman (R-OH) has hosted screenings of the film in his home state. The film’s director, Mary Mazzio, has become a prominent advocate of the legislation, producing a PSA with comedians Amy Schumer and Seth Meyers telling the camera, “#IAmJaneDoe.”

As FOSTA neared a vote in the House earlier this month, Mazzio’s production company used its marketing lists for lobbying, sending out a sign-on letteraimed at Congressional representatives to the film’s supporters. The I Am Jane Doe letter garnered support from groups like Expose Sex Ed Now, which advocates against comprehensive sex education, along with the National Decency Coalition, The Institute on Religion & Democracy, and Family Watch International, groups that lobby for the “traditional” family and who oppose abortion. Another signer, the National Center on Sexual Exploitation (formerly known as Morality in Media), has long led its own anti-sex work campaigns, blaming pornography for trafficking.

House Republicans have borrowed from these groups in their arguments for FOSTA. In his floor speech ahead of the FOSTA vote, Rep. Doug Collins (R-GA) said human trafficking was about “wicked men and women” who “turn vulnerable young people into sexual commodities.” Rep. John Duncan, Jr. (R-TN) blamed “family breakdown” and “addicting our children to computers” for human trafficking. Rep. Ted Poe (R-TX) called traffickers “filthy criminals” while standing in front of a mug shot of a Latina woman.

Some women’s rights groups and advocates who might typically oppose such religious right groups became their allies on SESTA and FOSTA. In addition to making the rounds among anti-abortion, pro-“family” organizations, the I Am Jane Doe letter was also circulated by the women’s rights organization Legal Momentum, a SESTA supporter. Nation columnist Katha Pollitt, who signed the letter, told The Appeal she didn’t know about the bill’s right-wing supporters since she received it from Legal Momentum. But she didn’t think it was fair, she said, to hold the signatories responsible for each other’s politics, adding, “Sometimes the bitterest enemies agree about one thing.”

Survivors Against SESTA

While alliances across the political spectrum have formed in support of the legislation, trafficking survivors and their advocates largely oppose it. They have told The Appeal that trying to outlaw websites like Backpage is not the same thing as fighting trafficking or supporting survivors. In fact, it can have the opposite effect: putting victims of trafficking in danger.

The legislation’s most immediate impact might be a chilling effect on website operators, leading them to preemptively crack down on content posted by sex workers. “SESTA is about making internet platforms afraid to host ads for the sex industry,” Kate D’Adamo, a partner with Reframe Health and Justice, told The Appeal. And that could leave sex workers in more dangerous situations, she said. FOSTA is currently broad enough to possibly apply to content sex workers share online to ensure safer working conditions, like “bad date” lists, client screening tools, and safer sex education. FOSTA, said D’Adamo, could “threaten the harm reduction mechanisms people are using to stay safe when working, but none of that matters if you don’t have access to a safer space [to advertise] anyway.”

Nina Besser Doorley, a senior program officer at the International Women’s Health Coalition, echoed her concerns. “By taking away one of the few tools that sex workers have to organize and to screen clients, this bill increases sex workers’ risk of violence, making it harder to identify and support survivors,” she said.

The Freedom Network, the largest national network of anti-trafficking service providers and advocates, also opposes the bills. “Further criminalizing consensual commercial sex work, where there is no force, fraud or coercion, is no way to protect victims,” the group states in a press release. “Websites have an instrumental role to play in the investigation and prosecution of traffickers. They should be further incentivized and encouraged to report potential signs of human trafficking (both labor and sex trafficking of adults and minors) and child exploitation.” FOSTA and SESTA, advocates say, could make such sites less willing to participate in investigations, or, by pushing the sites to shut down, eliminate them as an investigative tool in identifying victims.

Their closure could also leave these workers more vulnerable to homelessness, arrest, and violence, said Caty Simon, a harm reduction activist and sex worker in Western Massachusetts. She expressed fear for the community she serves, which includes sex workers who use drugs. “Some of these women have recently clawed their way into the lowest rung of indoor work and out of homelessness, posting online while overpaying for a motel room every night,” she told The Appeal. “They’re still unstably housed and they’re still dealing with all of the bullshit of criminalization and poverty, but still, they tell me they are much safer and their quality of life is much improved. SESTA will send these women back to the abusive managers, cop violence, rape, and monotonous misery of street work.”

LGBT rights groups share these concerns about abuse and criminalization. Sex workers and trafficking victims alike “would be subjected to increased violence, exploitation, and more incarceration,” said Tyrone Hanley, policy counsel at the National Center for Lesbian Rights. The National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE) also opposes the legislation. “Widespread discrimination leads many transgender people to engage in sex work to get by, and this legislation would make it even harder for them to keep themselves safe and find other economic opportunities if they choose,” said Kory J. Masen, racial and economic justice policy advocate at NCTE. “Limiting their access to safe working conditions and resources will exacerbate the problems of human trafficking, violence against women, and public health.”

Groups like NCLR and NCTE are relatively new to this conversation. They are among a range of national organizations that have not typically taken a stance on legislation that could harm sex workers but are now backing the cause. Meanwhile, sex workers and survivors of trafficking are leading a grassroots campaign (under the hashtags #LetUsSurvive and #SurvivorsAgainstSESTA). They are calling their senators and educating the public using social media. On Tuesday, NCTE and NCLR joined them to lead a SESTA briefing for Senate staffers.

Up to this point, opposition to these bills was primarily seen as coming from tech companies and their interest groups, who the legislation’s supporters claimed were willing to sacrifice women and children’s safety for “profit.” However, with opposition from national women’s and LGBT health and rights groups, it is clear the opposition is not just about tech companies’ attempts to protect themselves and their own bottom line. Besides, the Internet Association, a trade group that represents almost every major internet business — from Twitter to Amazon to PayPal to Netflix to Airbnb, and even Google — says that after certain changes were made to the legislation, its members are now in support.

The legislation’s opponents face an uphill climb. The alliance of anti-sex work women’s groups and religious right groups pushing SESTA and FOSTA has long been instrumental in winning bipartisan backing for these kinds of “anti-trafficking” bills in Congress, part of advancing a shared anti-sex work agenda. Yet in this case, perhaps the most significant coalition-building support came from Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg, architect of the women’s empowerment platform LeanIn.org. Sandberg’s endorsement, straddling feminism and Silicon Valley, even found its way into the daily email alert from House Majority Whip Rep. Steve Scalise (R-LA) on the morning FOSTA went for a floor vote.

If women’s rights and religious right groups could make common cause, so could Sheryl Sandberg and Ivanka Trump, another prominent supporter of the legislation. The first daughter, the White House said earlier this month, has met with trafficking survivors — along with the president. This administration, his press secretary insisted, will “ensure survivors have the support they need.” On Tuesday, Ivanka Trump gathered SESTA and FOSTA co-sponsors in the Roosevelt Room, along with I Am Jane Doe director Mazzio. “On behalf of the president,” Trump thanked the roundtable participants for their work “to end the shameful and tragic crime of online sex trafficking.”