He Rebuilt His Life After Prison. Then He Was Deported for a 23-Year-Old Drug Conviction.

Samuel Anthony moved away from Sierra Leone at six years old. That didn’t stop the U.S. from deporting him to a country where he doesn’t know anyone and doesn’t speak the most common language.

As a teen, Samuel Anthony committed a drug crime. But now, at 51 years old, Samuel continues to suffer for a mistake he made decades ago.

Samuel’s parents brought him to America from Sierra Leone when he was six. To cope with the pain and isolation he experienced as a child, Samuel turned to drugs during his teenage years. Eventually, he began selling crack to support his habit.

In 1991, Samuel was beaten into a coma after he intervened in an altercation between several men and a woman. At the hospital, police found drugs on him. A court gave him a suspended sentence and placed him under probation, but after he was found guilty of drug offenses a second and third time, a judge sentenced him to nearly 20 years in prison.

Samuel served his time and got out in 2011 after the U.S. Congress changed sentencing laws to reduce racial disparities between crack and cocaine sentencing. He was held in an immigration detention center for a year and a half before being released in 2012. Then, he set about rebuilding his life.

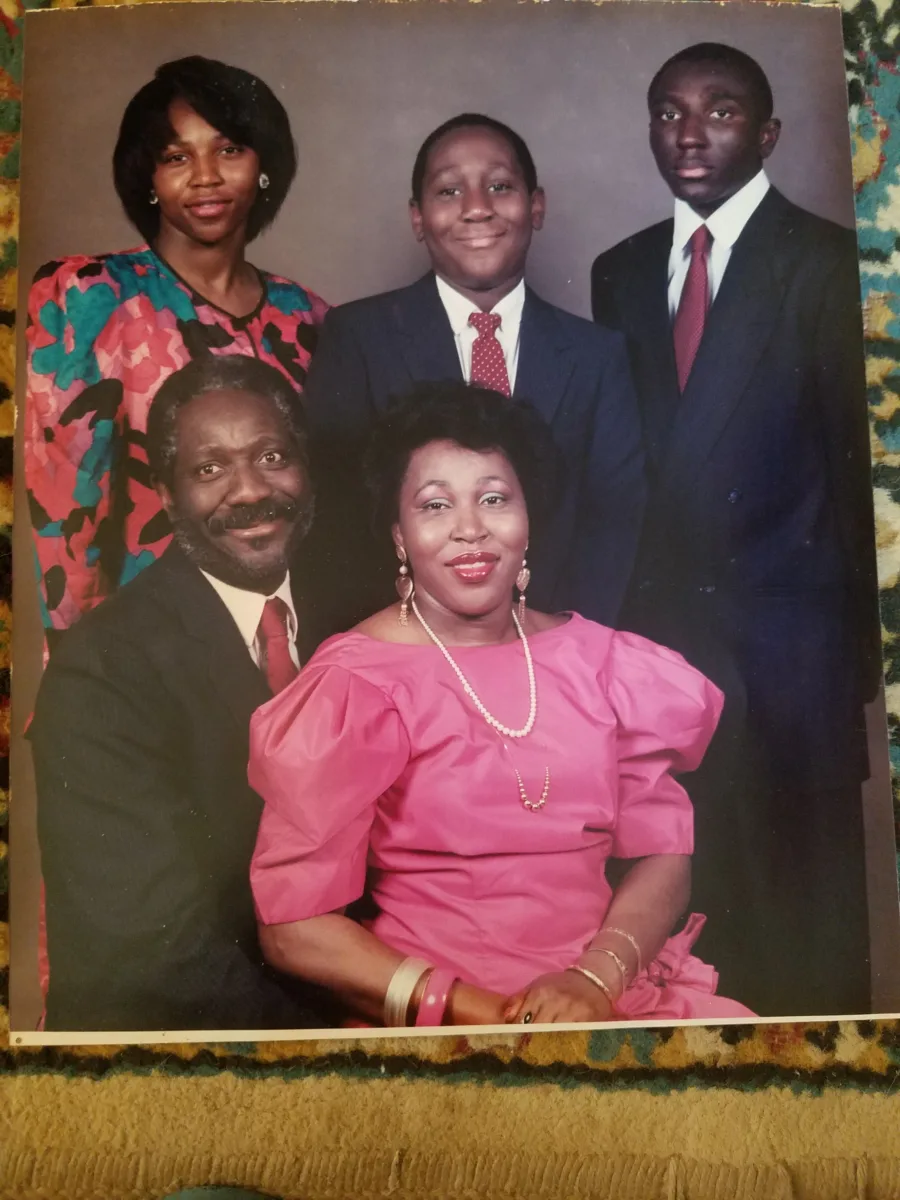

He got a job, showed up for his family, and bought a house. To Samuel and his family, it seemed he was doing everything right. He was happy. And his family was overjoyed to have him back in their lives.

But in 2019, the United States government deported Samuel without warning, citing his 1996 conviction as the reason why. Now, he is stuck in Sierra Leone, a world away from everyone he knows and loves, in a country where he does not speak the most common language and had not been since he was six years old.

“The mistakes you made at 19 should not define who you are at 52,” his sister, Samilia Anthony, told The Appeal. “I don’t know how you put on paper that a person is a good human.”

Samilia and their brother, Shanel Anthony, say that Samuel is an exceedingly kind person who has rebuilt his life and paid his debt to society. Both recall Samuel as the sort of person who—sometimes to his own detriment—would go out of his way to help others.

“My mom was like that—she talked to everyone, whether you were a homeless person or an executive in a bank,” Samilia said. “And Sam is like that. Just always gracious with people.”

Samilia said her brother used to take a boy at church out for ice cream. The child has since grown up. When he sees her at church all these years later, he tells Samilia how much Samuel’s small act of kindness meant to him.

When the government held Samuel in an immigration detention center after his release from prison, Shanel remembers Samuel calling him to ask how they could help an elderly man incarcerated alongside him.

Samuel has applied for immigration relief from the government. The Biden administration could let Samuel back into the country to reunite with his family—or keep him isolated across the ocean.

“I’ve tried to be doing the right thing,” Samuel told The Appeal. “I’ve repented. I’ve done all I’m supposed to have done. I got hooked on smoking drugs and started selling drugs to support my habit. The punishment is so harsh. When is enough enough?”

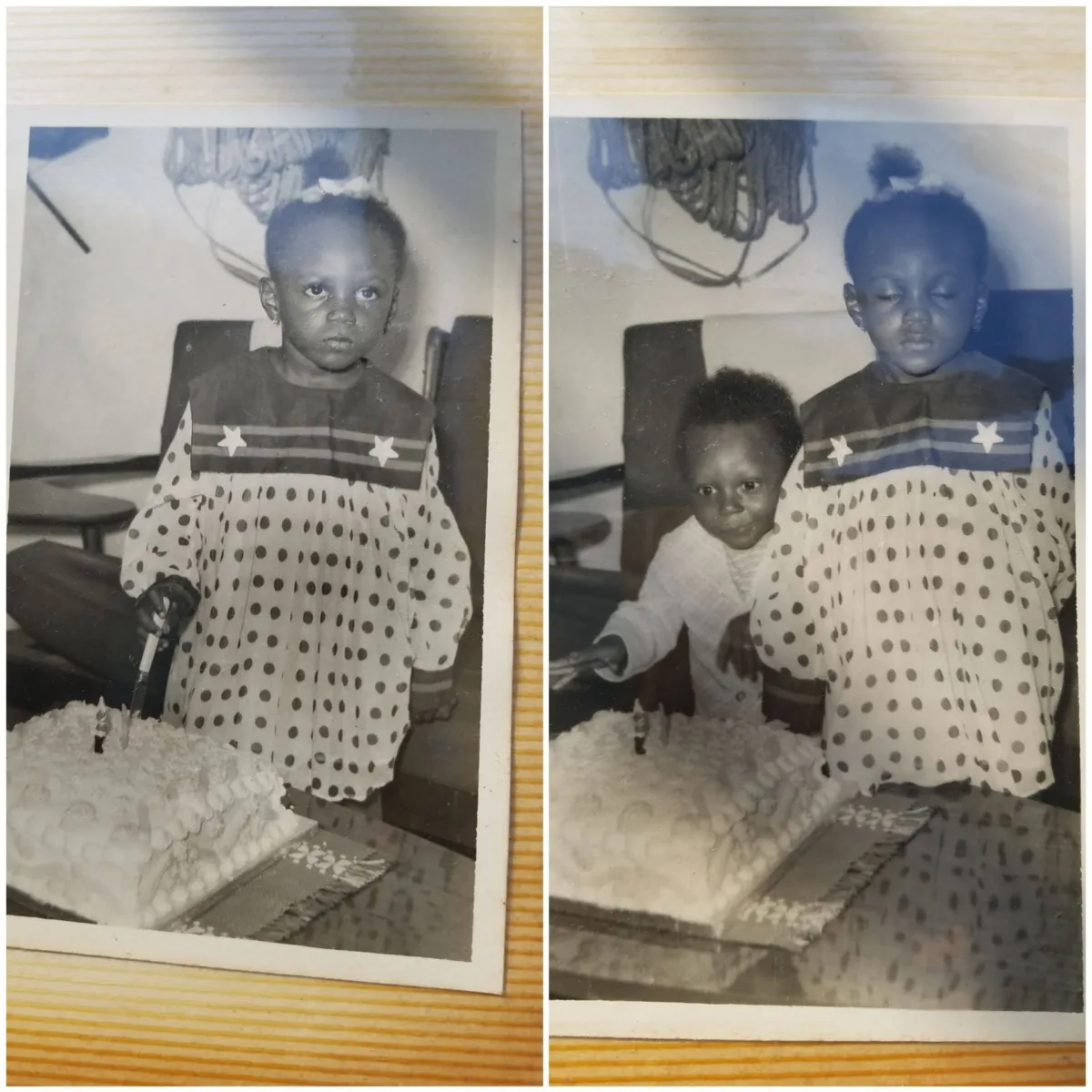

Samuel was born in Freetown, Sierra Leone in 1972. His parents moved to the United States shortly after, leaving 8-month-old Samuel and his two-year-old sister, Samilia, behind in West Africa with their grandmother. Samuel and Samilia joined their parents in Washington, D.C., about five years later. But the pair still spent a lot of time away from their parents, Samilia recalls.

“Our parents worked all the time,” Samilia said. “You were alone a lot. You had to find your own way.”

A pediatrician sexually abused Samuel one year after the boy moved to the United States. He was seven years old. As a teen, Samuel was bullied and struggled to fit in. By his late teens, he began using drugs.

“I became addicted to the drug PCP and used various other drugs and alcohol to cope with the pain that has haunted me since childhood,” Samuel said in his U-Visa application, a form of immigration relief available to people who have survived certain crimes that happened within the United States. “In connection with the substance abuse, I began selling drugs to support my addiction.”

In May of 1991, Samuel was arrested for the first time. He was 18 years old. According to police records and a psychiatric evaluation shared with The Appeal, Samuel was walking down a street in Washington, D.C., when he saw a group of men harassing a young woman. He tried to intervene, but the men beat him until he was unconscious. He was taken to a hospital, where he remained for several days.

Police searched Samuel while he was unconscious and found cocaine. Samuel was later convicted of drug possession with intent to distribute and sentenced to twelve months of supervised probation.

“That really is what started this trajectory for him,” Samilia said. “He just felt like his options were just limited at that point.”

After his arrest in D.C.—but before his conviction and probation order there—Samuel was arrested in Frederick County, Maryland, for cocaine possession. He received a four-year suspended sentence and three years of probation.

But in 1996, Samuel was prosecuted for drugs a third time. Federal prosecutors in Virginia charged Samuel and three co-defendants with conspiracy to distribute 50 grams or more of crack.

Samuel said he sold crack to support his own habit. But he alleged that prosecutors painted Samuel and his co-defendants as drug kingpins to punish them as harshly as possible.

“They never found anything that showed I was this big drug dealer,” Samuel said. “It was egregious.”

Police used a confidential informant to purchase drugs from Samuel and his three co-defendants. Samuel said the prosecutor wanted him to become an informant and testify against his friends. When he refused to do that, Samuel said, “he threw the book at me.”

Court records reviewed by The Appeal support Samuel’s claims and show that law enforcement officials did use an undercover cop to trick Samuel’s co-defendants. In various court filings, prosecutors described the alleged drug ring involved only four or five people selling small quantities of crack in a house to about two dozen people over a less than two-year period.

Afraid he could be sentenced to life, Samuel took a plea deal. He was 24. A judge ultimately sentenced Samuel to 19.5 years in prison and five years of supervised release.

“He told me I was going on a long trip, and I didn’t know when it was going to end,” Samuel said. “I’m now paying for it till I become old.”

Samuel spent the next 15 years in prison. In 2010, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act to reconcile racial disparities between sentences for crack and cocaine. When Samuel filed a motion for resentencing, prosecutors chose not to oppose it. The following year, Samuel was released from prison.

But he wasn’t free. He spent the next year and a half in the custody of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Samuel had a green card, but the government revoked it after his conviction.

“If you are convicted of a crime, the U.S. can strip you of your green card,” Samilia said. “He was too young to understand the ramifications of the decisions he was making.”

The government initiated removal proceedings against Samuel because he had been convicted of a felony related to trafficking in a controlled substance. Samuel said he spent two years in an immigration detention center but was released because the authorities could not get the travel documents necessary to deport him.

In 2012—then almost 40 years old—ICE released Samuel from custody and placed him on an Order of Supervision or OSUP, which freed Samuel from the detention center as long as he submitted to constant monitoring and regular check-ins. He was also under federal supervision due to the terms of his 1996 plea agreement.

“The whole process was intrusive and abusive—it’s like he never got out of jail,” Shanel, Samuel’s younger brother, said. Samuel had to regularly check into the ICE office in McLean, Virginia—about an hour’s commute from his home in D.C. He also could not work without the approval of the Department of Homeland Security and had to get a work permit.

Despite all this, Samuel rebuilt his life. He found work at retail stores and as a driver, bought a house in D.C., and started a mentorship program called Mentoring 2 Work. The program assisted people leaving prison who needed help finding employment and getting their lives back on track. Samuel was trying to turn the project into a nonprofit when he was deported, Samilia said.

Samuel also reconnected with his daughter, Samantha, who was only a year old when Samuel went to prison. She was 17 when he was released from ICE detention.

Samantha did not get to have her father in her life for many of her formative years. She said she was hurt by his absence and initially reluctant to let him into her life.

“But my Dad tried and put a lot of effort into us having a relationship and over time it worked,” Samantha wrote in a letter to immigration authorities. “Soon it became normal to have my Dad there.”

Samuel attended his daughter’s high school and college graduations. He fixed her car, took her out to eat, and supported her financially. For seven years, Samantha got to have her father in her life.

“We were building that love that I had for her and that she had for me when she was very little before I went to jail,” Samuel said. “I loved being able to be a real dad to her, someone who was there and who could spend time with her.”

After his 1996 drug conviction, Samuel worked hard to overcome his substance use disorder and rebuild his life. But in 2015, he slipped up. According to a statement made in Samuel’s U-Visa application by his friend, Jerome Crosson, the two were celebrating Jerome’s new job at Samuel’s home in D.C. when Jerome’s elderly mother called and said a pipe had burst in her basement at her home in Maryland. Jerome asked Samuel to drive him to his mother’s home so he could fix the issue before the basement flooded.

Samuel brought Jerome to Maryland, helped repair the pipe, and drove home. He got tired during the drive and pulled off to the side of the road to sleep. While Samuel was napping in the passenger seat with the car turned off, a police officer woke him up and asked to check his blood alcohol content (BAC). Samuel said his blood was drawn at a local hospital. His BAC was .09, just above the legal limit of .08. Samuel said he was allowed to go home that evening but was later sentenced to one year of probation for driving under the influence and unsafe operation of a vehicle.

Samuel and his attorneys said the 2015 conviction was not a part of the federal government’s argument when deporting Samuel or increasing his supervision. A notice from the Department of Homeland Security filed during Samuel’s removal proceedings states that he is removable from the United States because of his 1996 conviction. Documents related to Samuel’s removal proceedings shared with The Appeal do not list his 2015 conviction as a reason the government is removing him.

The government began removal proceedings against Samuel as soon as he was released from federal prison in 2011, according to court records filed by an assistant U.S. attorney against Samuel. Court records say ICE released Samuel from custody in 2012, because “Sierra Leone refused to issue a travel document that would permit ICE to effectuate removal.”

“Beginning in late 2017, ICE started having more success in acquiring travel documents from Sierra Leone for aliens with final orders of removal,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Patricia McBride wrote in court filings. Eventually, the government succeeded in obtaining travel documents from Sierra Leone.

In 2016, after Donald Trump became president and the federal administration changed, Samuel said the monitoring got more extensive.

“In 2016, they called me into the ICE office and turned my life upside down,” Samuel said. In addition to weekly check-ins at the ICE office, he now had to wear an ankle monitor and submit to weekly home visits from an ICE inspector. ICE did not provide a time window for the home visits, so Samuel would have to take off work and sit at home all day until the inspector arrived.

“I remember him complaining about ankle pains because that monitor was on,” Shanel said. “We’d take family trips, but he couldn’t come because of the ankle monitor.”

Samuel said the experience was “excruciating and demoralizing. It just uprooted your whole life. There were certain jobs you couldn’t do. How are you going to tell your employer you can’t come to work for a whole day because you have to sit and wait for an ICE inspector to come?”

Since he had to spend two days each week checking in with ICE, Samuel said he found it difficult to hold regular employment. So he ended up driving for Uber. But, thanks to his ankle monitor, he could only drive so far.

Besides working, Samuel spent time with his family and cared for his aging mother and father. When it snowed, he would shovel his sister Samilia’s driveway. He looked after his brother Shanel’s newborn baby. His mother, Gloria Anthony, had a chronic health condition, and Samuel drove her to her doctor’s appointments.

Then, one day, Samuel checked into the ICE office and never returned.

“It was like a death sentence,” Shanel said. “That was the worst nightmare.”

On July 31, 2019, ICE officers arrested Samuel during one of his biweekly check-ins. He said he walked into the ICE office just like he did every week, but this time officials directed him into a conference room. Then, four ICE agents rushed inside, threw him against a table, and arrested him.

The news shocked Samuel and his family.

“I’ll never forget,” Shanel said. “We were talking and he was like, ‘Alright, I gotta go check in.’ I was like, okay, you know, no big deal, this was something he did on a regular basis. And this time you go check in, and they’re like, ‘No, we’re keeping you.’”

During the Trump Administration, immigrant rights groups increasingly started calling these deportations “silent raids.” To Samuel’s family, it seemed like he disappeared. Samilia sensed something was wrong and called him over and over again, but the phone just kept ringing. They couldn’t reach him and had no idea what would happen to him next.

“I don’t think people understand how inhumane this process is,” Shanel said. “The underwear he had on, that’s what he had. The appointments he had that day, nothing. The car in the parking lot.”

Eventually, they learned the government wanted to deport Samuel. They contacted an attorney, called their congresspeople, and leaned on friends and family for support. ICE held Samuel in Virginia before moving him to a detention center in Texas.

Samuel’s family was able to delay his deportation by about five months. They said they felt hopeful they could keep Samuel in the country with his family.

But by December, they couldn’t delay any longer. Immigration authorities put Samuel on a plane to Sierra Leone and sent him to a country he hadn’t been to in over 40 years.

“I was totally devastated when he was deported,” Samilia said. “He had been out of jail for about seven, eight years, got a job, got a house, rebuilt his life with us with his daughter.”

Since Samuel arrived in Sierra Leone in 2019, he has not been able to return to the United States. While English is one of the country’s official languages, he does not speak Krio—the language spoken by most of the population—or any of Sierra Leone’s other indigenous languages. He doesn’t know the culture. He is four hours ahead of everyone he loves and 4,500 miles away from them. Because Samuel did not know he was going to be deported, he never got to hug any of his family members goodbye.

“I would rather have been in prison than be here,” Samuel said. “I just want to have a normal life. I want to feel whole again.”

He says he has been unable to get a job, so he depends on his family to support him. As an American deported to Sierra Leone, Samuel says others either view him as a criminal or someone wealthy they can exploit.

In 2021, Samuel’s mother died. He applied for humanitarian parole to return to the United States for her funeral, but the U.S. government denied his request.

“That part I haven’t quite gotten over,” Samilia said through tears. “So he was not about to honor her and say goodbye as he would have liked and I would have liked.”

Shanel said Gloria was traumatized by Samuel’s removal, and her health began to decline.

“The last thing she asked her home nurse before she died was how Samuel was doing?” Shanel said in a letter to immigration authorities.

Samilia and Shanel are still fighting to bring their brother home. Because Samuel was the victim of a crime in 1991 where he suffered severe injuries, his attorneys say he is entitled to a U-Visa.

Sarah Gillman and Delia Addo-Yobo, two attorneys with the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights organization, filed a U-Visa application for Samuel with the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). Samuel is still eligible for the visa despite his conviction.

Samuel’s attorneys say he applied for a U-Visa before he was deported.

“He had a pending U-Visa—there really wasn’t any need for immigration to detain and deport him,” Gillman said. “The United States government could make right what’s been done to Samuel and his family immediately. It’s just as easy to bring someone back as it is to deport them.”

Gillman and Addo-Yobo have also requested that the government grant Samuel humanitarian parole so he can come home and be with his family while his U-Visa is pending.

USCIS did not respond when contacted for this story.

In Sierra Leone, Samuel says he is isolated and depressed. Samilia says that each time she talks to her brother, he sounds worse. In a psychiatric evaluation shared as part of Samuel’s U-Visa application, a healthcare practitioner noted that Samuel barely eats or sleeps, has lost interest in social activities, and suffers from constant negative thoughts and suicidal ideation.

His family continues to support him from afar. But Samuel’s abrupt deportation also upended the lives of everyone who loves and depended upon him. Samuel’s father’s health has declined. Shanel started taking blood pressure medication due to the stress and started seeing a therapist. Shanel’s son, Luke, doesn’t understand where his uncle went.

In the meantime, Samuel’s family’s lives continue without him. He missed his father’s 80th birthday. He missed his daughter Samantha’s graduation from a master’s program in social work.

“It was very emotionally devastating to have my Dad taken from me,” Samantha wrote in her father’s U-Visa application. She has not seen her dad since he was deported more than four years ago. “I would like him home again so that the bond we began to build upon his release in 2012 can continue.”

Samuel’s life now sits in the hands of the Biden administration. If the federal government denies Samuel’s U-Visa application, he may be unable to reunite with his family for the rest of his life—all because of a drug crime he committed nearly three decades ago when he was 23 years old.

“I don’t want to die in this country,” Samuel said. “I’m not happy here. My heart is not here. This is not my home.”