New Lawsuit Claims a Sacramento Deputy Unlawfully Arrested Activist Who Protested Clearing Of Homeless Encampment

Advocates and homeless people are suing Sacramento County over its treatment of homeless—and the city responded by filing a lawsuit against seven men for being a ‘public nuisance.‘

On May 17, Crystal Sanchez heard that Sacramento County, California, sheriff’s deputies were making arrests at a vacant lot on Stockton Boulevard. Sanchez, an advocate for homeless people, went to the lot to see if she could help.

At the encampment, a sheriff’s deputy who had previously seen Sanchez helping people there spotted her. Deputy Daren Allbee called out her name, handcuffed her, and accused her of driving without a valid driver’s license, although she wasn’t driving her car at the time.

Allbee then told Sanchez he was going to tow the car, even after several people nearby offered to drive her car back to her home. When Allbee refused the group’s request, they offered to take the food and equipment out of Sanchez’s car, so it wouldn’t be spoiled or stolen. But Allbee said he planned to impound the vehicle for 30 days.

Then Allbee placed Sanchez under arrest for driving without a valid license. “I got one of the protesters,” he allegedly said as he detained her.

On Aug. 12, Sanchez sued Sacramento County, the sheriff’s department, and Allbee for violating her civil rights by arresting her without probable cause and unreasonably seizing her property. In the federal lawsuit, Sanchez alleges that Allbee “retaliated against her because of her leadership position on providing assistance to homeless persons camped at the 5700 Stockton Boulevard lot.”

Nearly three months after her arrest, Sanchez still hadn’t been able to raise the $1,600 she needed to retrieve her car, which has the phrase “Everybody’s got a right to live” written on its windows.

Allbee has previously been named in six lawsuits filed in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of California. All of the lawsuits were filed pro se, or without attorneys, by people incarcerated in California state prisons and county jails. In 2006, Herbert Bellinger Jr. won a $750 settlement in a lawsuit he filed from prison against Allbee and Sacramento County. Bellinger alleged that Allbee and other sheriff’s deputies used excessive force and racially discriminated against him. According to the lawsuit, Allbee reprimanded Bellinger for not removing braids from his hair. When Bellinger didn’t obey his commands, guards allegedly shackled him, cut off his braids and called his hair “nappy.”

In 2015, Michael Lenoir Smith alleged in a lawsuit that he had witnessed Allbee “‘ruthlessly attack’ African-American inmate Ernest Walker.” (Walker filed his own lawsuit against Allbee, but it was dismissed for failure to comply with court orders.) Smith claimed that after deputies assaulted inmates, they “would fabricate ‘spurious incident reports’ to cover up their own misconduct.” After Smith filed a grievance, Smith alleges, Allbee attacked him, then falsely accused him of assault to cover it up.

Smith was acquitted of the charge, but in a lawsuit he later filed against the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation he claimed his prison records “perpetuated a false statement from his Sacramento County records that plaintiff had been convicted in 2002 of attempted murder of a peace officer.” Smith’s case is ongoing.

When reached by The Appeal for comment on the multiple complaints against Allbee, the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department said in an email that it would not comment on pending litigation, but said the $750 paid out to Bellinger was most likely a “cost saving decision” by the county that “doesn’t necessarily reflect misconduct on the part of any personnel.” The complaints against Allbee, a sheriff’s department spokesperson said, “are serious claims and, if true, could expose the County to much more than a $750” payment.

In 2019, Crystal Sanchez’s attorneys, Mark Merin and Paul Masuhara, filed a separate lawsuit that accused Sacramento law enforcement of violating the rights of people protesting the police killing of Stephon Clark, an unarmed Black man, in his grandmother’s backyard. In 2019, when the Sacramento County District Attorney Anne Marie Schubert declined to prosecute the officers responsible for Clark’s death, protesters marched through the city, eventually making their way through “the affluent ‘Fab 40s’ neighborhood of East Sacramento,” the complaint states, an act met by police with the arrest of 84 protesters and one Sacramento Bee reporter.

“The March 4, 2019, demonstration was the first to occur in a wealthier, predominantly-white area of Sacramento. Unlike prior demonstrations involving the death of Stephon Clark occurring in other locations within Sacramento, the March 4, 2018, demonstration was the first to involve a mass arrest response by law enforcement,” according to the lawsuit.

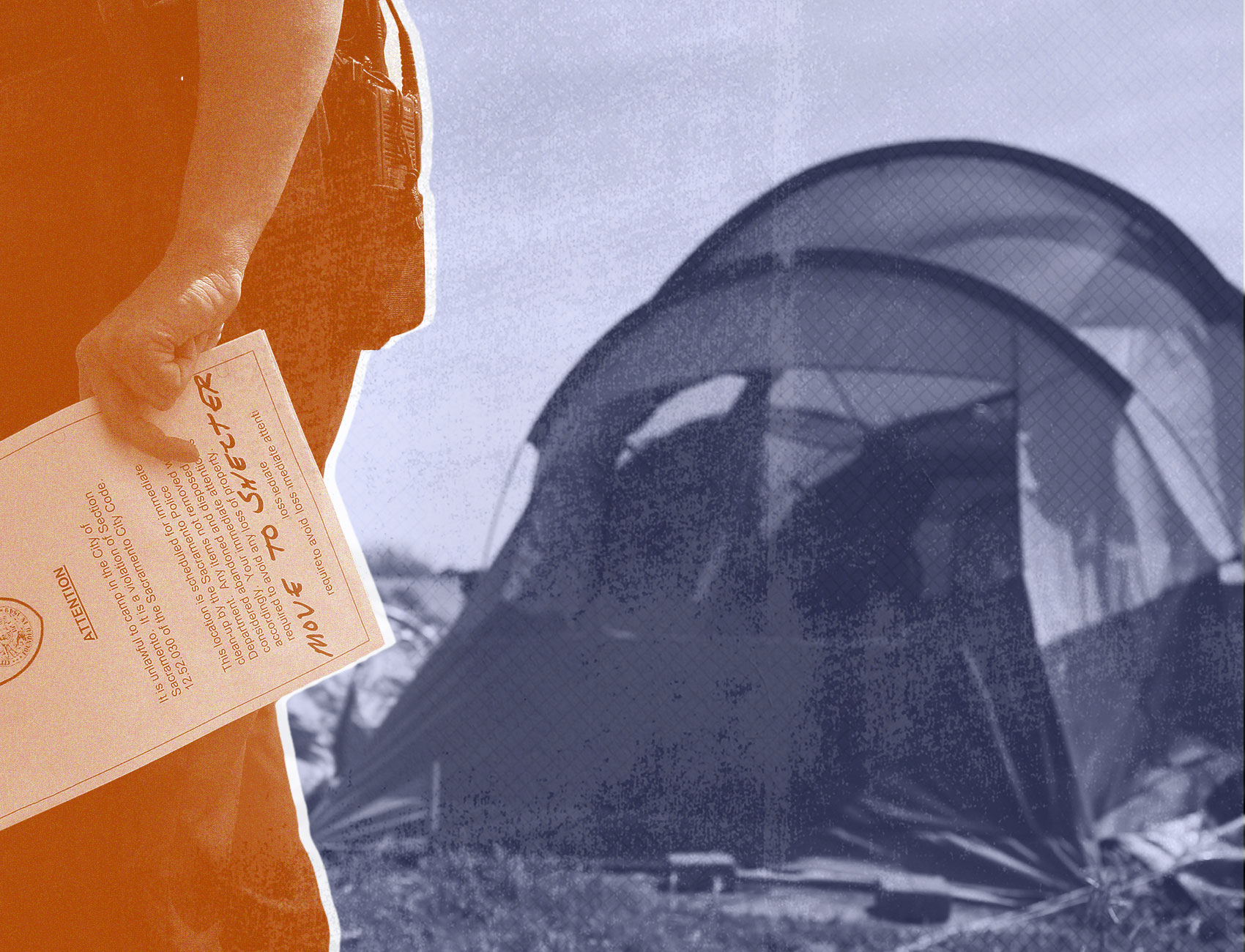

Sanchez’s claim that she was targeted for protesting the removal of homeless people from an encampment came after months of crackdowns by law enforcement. On April 28, residents of the nine year-old Stockton Boulevard homeless encampment where nearly 100 people lived were given three days’ notice to vacate. The lot is owned by the Sacramento Housing and Redevelopment Agency, which plans to build affordable housing on the site, though the development has not broken ground.

Advocates for homeless people have asked city officials to allow them to stay at the encampment until construction on the development starts.

“This is really just a system where they’re pushing people out from different areas at will without any real notice, and it’s just not fair to these people that don’t have anywhere to go and are often losing their possessions in the process,” said Masuhara. “It takes a toll, beyond just the regular toll of being homeless.”

Across the country, cities are looking for ways to push homeless people out of sight without improving access to shelters and resources. In August, the Boston Police Department’s “Operation Clean Sweep” deployed officers to forcibly remove homeless people from an area in the South End known as the “Methadone Mile” for its concentration of shelters and recovery services. At least 34 people were arrested while other homeless people were told not to return, but given nowhere else to go. As a part of the sweep, police also destroyed homeless people’s belongings, and even tossed wheelchairs into a garbage truck.

In July, Austin eased restrictions on “public camping,” making it more difficult for police to arrest homeless people simply for sleeping on the street. But the move has been met with pushback from Republican Party leaders in Texas and local business owners who say the presence of homeless people is a threat to public safety and property values. In Los Angeles, lawmakers are considering placing new restrictions on where homeless people can sit or sleep. The new rules would ban people from sleeping on streets and sidewalks within 500 feet of parks and schools.

The fight over homelessness is particularly consequential in Sacramento County, where the unhoused population has increased by 19 percent in the last two years. According to Sacramento Steps Forward, the county’s homeless services agency, there are 5,570 people living in shelters and on the street. Nearly 4,000 homeless people in the county do not have access to shelter.

On May 1, sheriff’s deputies forcibly removed residents from the Stockton Boulevard encampment at the direction of the Sacramento Housing and Redevelopment Agency. That day, Sanchez was also at the lot with dozens of other protesters. According to her lawsuit, Sanchez came into contact with Deputy Allbee that day as well. Sanchez said she tried to help homeless people pack their belongings after they were kicked out, but Allbee prevented her from doing so. Sanchez claimed Albee told her that she was “this close to being arrested.”

On May 22, three homeless people who lived in the encampment—Betty “Bubbles” Rios, Lucille Mendez, Palmer Overstreet—and the Sacramento Homeless Organizing Committee filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against Sacramento County, alleging that its policies against homeless encampments are “unlawful and unconstitutional.”

The county “deployed a fleet of Sheriff’s Deputies, some of whom were outfitted with batons and riot gear,” a helicopter, and at least 15 police vehicles to kick people out of the encampment, according to the lawsuit. During the raid, “residents were forced to frantically take the items they could carry, leave critical items behind, and flee to the surrounding sidewalk and nearby streets. Notably, Defendants did not deploy social service agencies, mental health professionals, or shelter providers.”

Rios, Mendez, and Overstreet say their possessions were lost or destroyed when sheriff’s deputies forced them out of the encampment. Rios alleges that a deputy rebroke her arm when he grabbed her. She was taken to a hospital for treatment, but when she came back her belongings were gone, including “her breathing machine, bone stimulator, and medication,” according to the lawsuit.

“The raid left individual Plaintiffs even more destitute, defenseless, and vulnerable,” wrote Laurance Lee, one of the plaintiffs’ attorneys.

Rios, Mendez, Overstreet, and the Sacramento Homeless Organizing Committee are seeking a permanent injunction to stop the county from criminalizing homeless people, seizing and destroying homeless people’s property, and forcing homeless people who cannot obtain shelter out of public spaces.

But on Aug. 9, the city of Sacramento filed a lawsuit against seven men accused of causing a “public nuisance” in a popular business corridor. The city is asking the court to ban the men from certain areas of the city.

“I’m really concerned about the lawsuit,” Paula Lomazzi, executive director of the Sacramento Homeless Organizing Committee, told The Appeal. “I don’t think it’s right to exclude someone from a certain area. What’s that solving? What they really need is outreach services and housing. The city really needs to learn to work with homeless people.”

In its lawsuit against the seven men, the city refers to them as “drug users, trespassers, thieves … and violent criminals” who have disturbed business owners along the corridor and must be forced out. The city also says that the presence of the men in the area where they reside has resulted in “negatively affected” property values and that “a sense of fear among citizens permeates the area.”

“Homelessness is not a crime, and this lawsuit does not seek to make it one,” Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg wrote in a statement emailed to The Appeal. Steinberg says the lawsuit seeks to protect “residents and businesses in the Broadway corridor who have been subjected to ongoing criminal activity by a relatively small number of people, some of whom also happen to be homeless. It is not a civil right to consume drugs in public, expose oneself in public, assault members of the public or steal from local businesses.”

In an emailed statement, Sacramento City Attorney Susana Alcala Wood told The Appeal that the city believes “injunctive relief” is appropriate in this case because “the residents and businesses along the Broadway corridor have been subjected to ongoing criminal activity from a relatively small group of people.”

But while there are a handful of thefts and assaults mentioned in the 71-page lawsuit, the “criminal activity” described in the lawsuit by residents involves trespassing, panhandling, urinating in public, and substance use.

Masuhara, one of Sanchez’s attorneys, says the city’s move to ban certain people from a specific area of the city is alarming and unusual. Because it’s a civil case, not a criminal one, the men have no due process and no right to counsel. “We feel like that’s a go-around, essentially,” Masuhara said. If the men don’t respond to the suit, Masuhara added, the court may simply grant the city the relief it has requested. “We feel it’s unconstitutional … Obviously it’s hitting the people that have the least amount of resources to combat this sort of thing. It’s just not a good look.”

“We are concerned about the precedent this could set if this is allowed to go forward,” Masuhara said. “If a judge lets that go forward, what’s the next case going to look like? Who gets to decide that someone is such a bad person that they can’t be in a certain area of the city?”