Georgia’s Unique Death Penalty Law Is Killing the Mentally Disabled

Georgia is the strictest state in America when it comes to proving intellectual disability in capital cases. This month, the Supreme Court could save the life of a man who says he is mentally disabled—or let the state kill him.

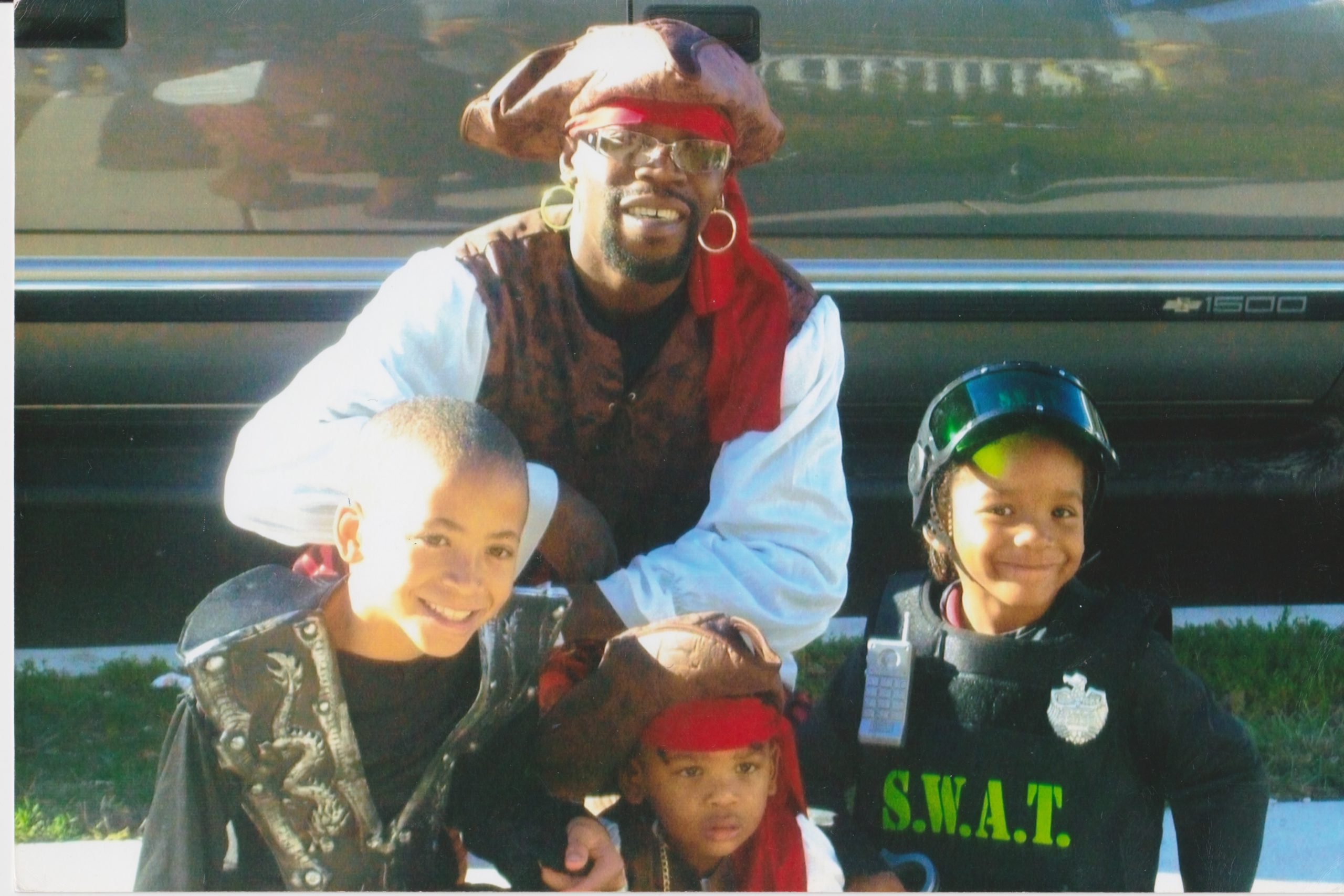

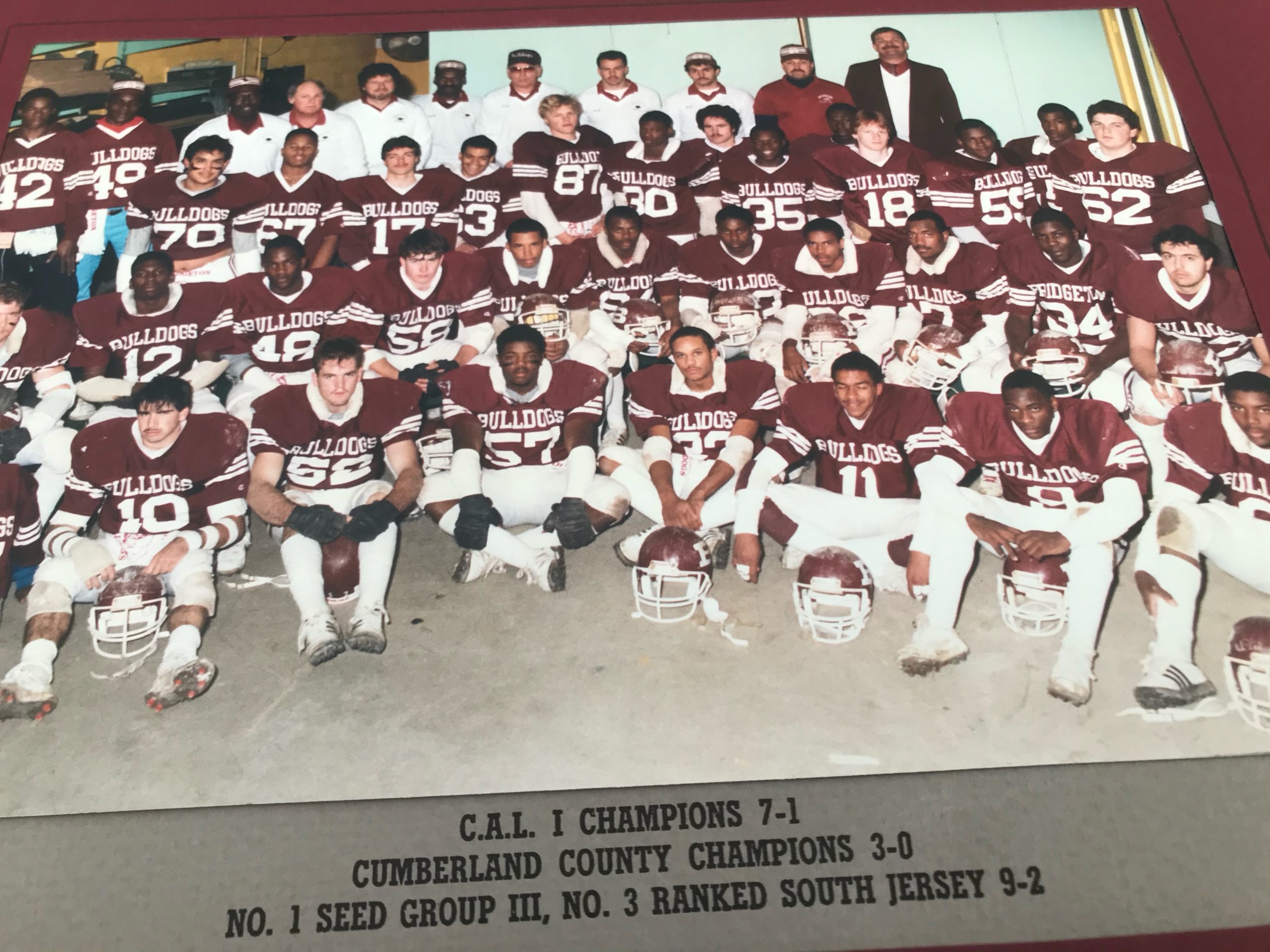

Before Rodney Young was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death, he was a high school football star. Young, now 54, played running back for the Bridgeton High School Bulldogs in Bridgeton, New Jersey, in the mid-‘80s, leading the team to a state championship game and winning offensive MVP. According to those who knew him, he was one of the best running backs the school had ever seen.

“He was just strong and fast,” his former coach, Don Reich, told The Appeal.

Reich recruited Young to play for him while he was working in the school’s special education department, where Young was enrolled in a program for students with intellectual disability. Young excelled at running the ball, but his disability caused him to struggle with football’s rules, especially the team’s intricate defense that involved fast-paced play-calling and maneuvering. Reich said Young had so much difficulty understanding the team’s tactics that he avoided putting Young on defense altogether.

Off the football field, Young worked hard in his classes, but was unable to keep up with his peers. He functioned at a third-grade level, according to one of his teachers who testified at his 2012 trial. On a standardized state achievement test, Young scored 5 out of 25 on reading comprehension, and 1 on math. He scored a 440 out of 1600 on the SAT. At the time Young took the SAT, participants received 200 points on each section for filling out their names.

In 2008, Young drove from New Jersey to Atlanta and killed Gary Jones, the 28-year-old son of his former girlfriend, Doris Jones. At trial in Newton County, Young’s lawyers entered a plea of “guilty but mentally retarded,” arguing that jurors should spare him of the death penalty because of his intellectual disability. In February 2012, Young was convicted of murder and sentenced to death.

Though the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that it is unconstitutional to execute an intellectually disabled person, the requirement in Georgia for determining “intellectual disability” all but guarantees that the disabled will die. Defendants must show “beyond a reasonable doubt” that they are intellectually disabled — a standard that is usually only reserved for convicting someone of a crime. In practice, that burden has proven nearly insurmountable.

In the more than three decades since Georgia’s law was enacted, there are no known cases in which a person found guilty of intentional murder in Georgia has successfully proved to a jury they were intellectually disabled.

Now, Young’s lawyers from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) are fighting to get him off death row, alleging that the state’s rule for proving intellectual disability violates the Constitution. The civil-rights group filed a petition with the U.S. Supreme Court in November asking judges to review the law, which Young’s attorneys say creates an “unacceptable risk of unconstitutional execution.” Justices are expected to decide this month on whether to take up the case. If they do, their decision could save Young—and four other people on death row who say they are intellectually disabled—from execution.

Wayne Hendricks was the head of special education at Bridgeton High School when Young was enrolled there. He knew Young as a “big teddy bear” who came from a close-knit family. To Hendricks, the idea of Young tying Jones to a chair with a telephone cord then beating him to death with a hammer and baseball bat seemed incomprehensible. “It was kind of hard for me to believe that he would ever be accused of what he had been accused of,” he told The Appeal.

In 2012, Young’s lawyers asked Hendricks to travel to Georgia to tell the jury what he knew about his former student’s intelligence in hopes that the jury would determine Young ineligible for the death penalty. For the jury to decide that Young was intellectually disabled, Young would have to meet a three-prong test that showed his intelligence was subaverage, his disability had emerged before the age of 18, and that he had problems with everyday activities or life skills.

Hendricks’ knowledge of Young during high school, along with the knowledge of other teachers who testified, formed the bulk of evidence of Young’s intellectual disability. His school records had already been destroyed, per the school district’s retention policy. Young’s lawyers had opted against including testimony from an expert, such as a psychologist, over concerns that the prosecution could use it to their advantage.

On the stand, Hendricks testified that Young would have had to score between 60 and 69 on an IQ test to be placed in the special education program, a range deemed by experts to be indicative of intellectual disability. It was district policy that every student in the special education program be given a battery of initial tests to determine eligibility, and then tested again every three years. All special education students, including Young, were assigned a psychologist, learning disabilities consultant, and social worker, who met each year with their student’s teachers to ensure that the child still qualified for the program, testified Hendricks.

Young’s lawyers also argued that his lack of life skills showed his intelligence was subpar. Young lived in his aunt’s basement, relied on his girlfriend to pay bills, and would often walk around with uncashed checks, they said.

The prosecution was led by Alcovy Judicial Circuit District Attorney Layla Zon, who made headlines a few years later for keeping “Death Row Marv”—a talking toy figurine of a character from the comic book “Sin City” being executed in an electric chair—in her office. (Lawyers in a separate case argued the toy showed Zon was “pathologically obsessed” with the death penalty, though she has denied those accusations.) Zon sought the death penalty for Young ahead of her first election, rejecting his plea offer for life in prison without the possibility of parole.

In the courtroom, Zon was determined to convince the jury that Young was not intellectually disabled. Her argument relied on assertions that Young was able to do things like read and write letters, watch television shows on forensic science, and hold a factory job putting labels on cans—something she claimed, contradictory to scientific literature on the matter, proved Young was of average intelligence. To support her theory, Zon called two people who worked at the factory with Young to testify, remarking, “Isn’t it odd that if the defendant is really as mentally retarded as they claim he is, that these men can do this same job and Rodney’s capable of doing it as well?”

In one exchange with Hendricks, prosecutors asked him if he thought it was surprising that Young could use the internet. Hendricks told The Appeal he was frustrated that prosecutors challenged Young’s intellectual disability. “It was difficult for me because they were describing someone that they didn’t know as well as I did,” he said. “And sometimes you want to just scream or object to some of the things that they were saying.”

In Zon’s closing argument, she told the jury at least ten times that in order for Young to escape the death penalty, they had to find him intellectually disabled beyond a reasonable doubt. “If you’re in the back deliberating this case, and you say, you know, I just don’t feel comfortable calling him mentally retarded, this just doesn’t, we are taking a big leap here, you know, then that’s a reasonable doubt,” she said.

Georgia was the first state to prohibit the execution of people with intellectual disability, doing so 14 years before the U.S. Supreme Court prohibited the practice in 2002. In 1988, legislators enacted the state’s “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard for determining intellectual disability in death penalty cases, in response to the state’s 1986 execution of Jerome Bowden, who could not count to ten.

The measure was intended to ensure that intellectually disabled people were protected from execution. Under the then-new law, people facing capital murder charges would automatically be sentenced to life in prison if the jury found beyond a reasonable doubt that they were guilty, but intellectually disabled.

But the new law didn’t work. Lauren Sudeall, a professor at Georgia State College of Law, conducted a study of the measure, finding that of 14 capital murder cases in which the 1988 “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard might have applied, no one had succeeded in claiming intellectual disability.

The state’s legal standard “creates a scenario in which it’s very likely that someone who, in any other circumstance would be seen as intellectually disabled, wouldn’t be, and then is executed in violation of the Eighth Amendment,” Sudeall told The Appeal.

There was just one case since 1988 in which a Georgia jury agreed to grant an intellectual disability claim: an unintentional, rather than intentional, murder. In 1998, a woman named Vernessa Marshall and her boyfriend accidentally killed Marshall’s 10-year-old son Jamorio by taking turns beating him with a belt after the boy had stolen $5 from another student at school. Marshall had been classified early in her own schooling as intellectually disabled and continued to wet her bed and suck her thumb until age 10. Marshall was found “guilty but mentally retarded” and sentenced to life in prison.

In 2015, Georgia executed a man named Warren Hill, despite assertions from every mental health expert who had ever evaluated him—including those for the state—that he was intellectually disabled.

The state was similarly persistent in its efforts to execute Willie Palmer, who’d been charged with the 1995 killings of his estranged wife and stepdaughter in Burke County. He was tried four times for the crime. During his second trial in 2007, a defense expert testified that, at age 10, Palmer was unable to put his shoes on the correct feet without help, and could not read an analog clock in his teenage years. Palmer’s IQ scores were consistently low, leading the expert to conclude that Palmer was intellectually disabled beyond a reasonable doubt.

The prosecution didn’t call on an expert to respond, instead telling jurors, “If you don’t want to use a number, don’t use a number. You can declare somebody with an IQ of 130 mentally retarded in this courtroom today. Or you can declare someone with an IQ of 30 not mentally retarded in this courtroom today.” Although the jury found Palmer guilty of capital murder, Palmer’s legal team later learned that the state declined to present testimony from an expert who, during the first trial, had originally been set to testify that Palmer’s intelligence was within normal limits. But after finding out that Palmer had qualified for Social Security benefits early due to his disability, the expert changed his mind. The state did not share the updated opinion with the defense, however, charging that Palmer’s lawyers should have discovered it themselves.

Palmer went on to be tried two more times before the death penalty was taken off the table because of prosecutorial misconduct.

Another man named Warren King was sentenced to death for the 1994 fatal shooting of a convenience store clerk. As a child, King was enrolled in special education classes and held back several times. Georgia’s own expert witness did not challenge King’s claim of intellectual disability, but prosecutors did. The state told the jury King was simply “not as well educated as he ought to be.” To bolster their claim, prosecutors used the fact that he had a driver’s license. King was found guilty in 1998 and remains on death row.

Other death penalty states set less stringent standards that make it easier for people to prove intellectual disability, according to Sudeall’s study. Of the 27 states with the death penalty, 19 states have a “preponderance of evidence” standard—a standard of proof that requires showing there’s a greater than 50 percent chance the claim is true. Four other states have a “clear and convincing evidence” standard, which means proving that a claim is substantially more likely to be true than untrue. The rest don’t have a standard.

Researchers have found that 371 people facing the death penalty nationwide between 2002 and 2013 raised claims of intellectual disability. Fifty-five percent of those were successful. In North Carolina, that figure was 82 percent. The statistic was 57 percent in Mississippi. As of 2017, Georgia’s rate was 7 percent due solely to Vernessa Marshall’s case.

Only two states had lower success rates: Florida and Tennessee. Florida had enacted a strict IQ cutoff of 70 to gauge intellectual disorder. But the U.S. Supreme Court struck that standard down in 2014, writing that the state’s IQ cutoff violated “our nation’s commitment to dignity[.]” Tennessee, meanwhile, passed legislation last year making it easier for people on death row to challenge their death sentences on the basis of intellectual disability.

Several people have challenged Georgia’s statute in court in an attempt to put the state’s laws in lockstep with those of other death penalty states. But the Georgia Supreme Court has always upheld the burden as constitutional and the U.S. Supreme Court has never heard arguments on it, despite an admission from one of the bill’s original co-authors, lawyer Jack Martin, that the law was a mistake. Martin helped draft the bill when he worked with the Georgia Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers’ advocacy group.

“It was sloppy draftsmanship, pure and simple,” Martin testified in 2013, during a legislative listening session on the statute. “I don’t think anybody intended that to happen.”

In a telephone interview with The Appeal, Martin said that the authors of the statute had meant for defendants to have to prove it was more likely than not they were intellectually disabled. The authors had previously sidestepped adding in clearer language because they were nervous the attorney general would withdraw his support. “We thought that that might hurt our chances of passing because it was such a new idea,” Martin said. “In retrospect, that was probably a mistake.”

Despite criticism from defense attorneys and disability-rights advocates, there has been little legislative will to change the statute. The last effort, in 2018, failed.

Without action from the legislature, Young’s lawyers have had to turn to the courts. But there has been little help there either. Last year, the Georgia Supreme Court rejected Young’s claim, ruling that he “failed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt” that he should be spared from the death penalty because of his disability. One justice dissented, writing that the burden increases the risk that an intellectually disabled person will be executed.

U.S. Supreme Court justices will convene this month to review Young’s petition on February 25. The court can either decide not to hear his case, to accept the case for review, or to delay their decision until another meeting. Historically, this Supreme Court has not been kind to people on death row claiming intellectual disability. In the past four months, justices have greenlighted the executions of two men in Alabama who said they were intellectually disabled. Both have since been executed.

To Hendricks and Reich, two of the men who’ve known Young since high school, it seems obscene that the Supreme Court would need to debate whether he has an intellectual disability. “I don’t condone murder,” said Reich. “I just don’t think in this case, the death penalty is warranted.”

Editor’s note: This article originally stated that students in the special education program at Young’s high school were assigned psychiatrists. This is incorrect. They were assigned psychologists. Additionally, this article originally claimed that more than a dozen other people could be saved from death row in Georgia if the Supreme Court overturns Georgia’s intellectual disability law. In fact, Young’s lawyers have identified four other people who could be saved from death row in Georgia. This story also originally included a photo of a man erroneously identified as Rodney Young. We regret these errors.