Political Report

Colorado Abolishes the Death Penalty and Ends Prison Gerrymandering

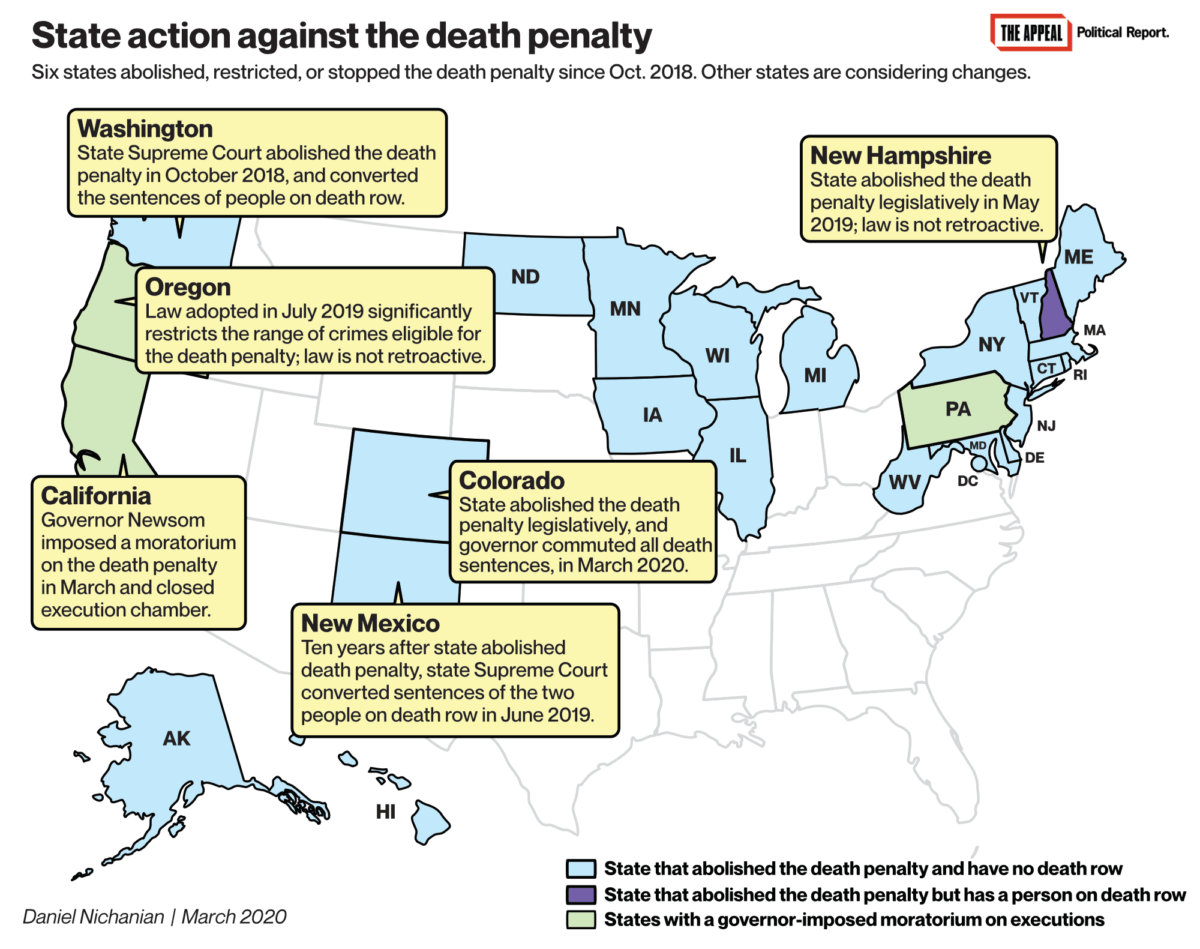

Nationwide efforts against the death penalty and against prison gerrymandering have gained considerable momentum just over the past two years.

Nationwide efforts against capital punishment and against prison gerrymandering have gained considerable momentum just over the past two years.

Colorado hit two milestones this month. It abolished the death penalty, a long-sought win for criminal justice advocates.

“The state of Colorado is out of the killing business,” Denise Maes, the policy director at the ACLU of Colorado, told the Political Report.

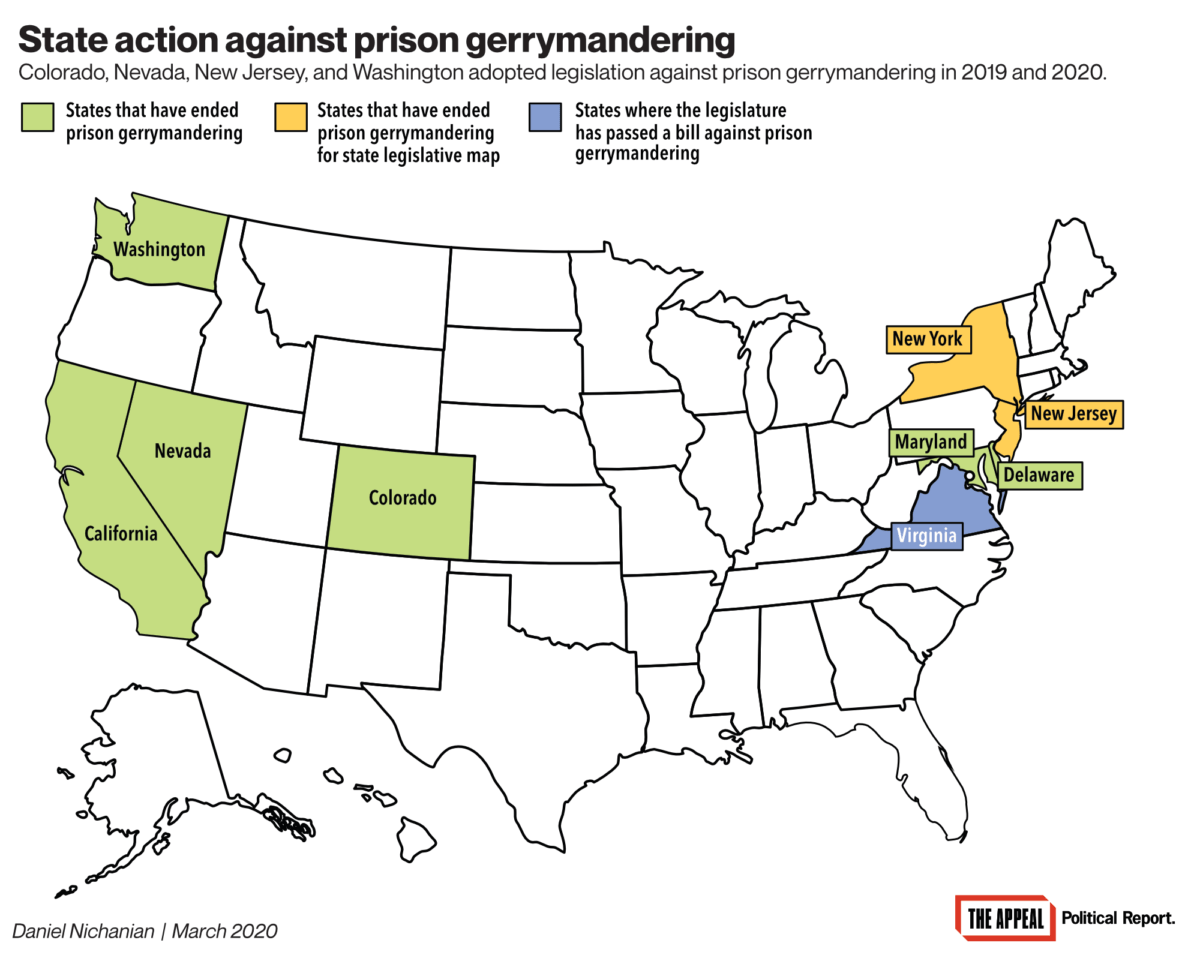

Colorado also ended prison gerrymandering, which is the practice of counting incarcerated people at their prison’s location rather than at their last address during redistricting. This practice shifts power from cities and more diverse communities, which suffer the brunt of mass incarceration, to the more white and rural areas where prisons are often located.

Governor Jared Polis, a Democrat, signed these two bills into law in recent days; the legislature had adopted them in February.

On Monday, Polis also commuted the death sentences of all three people on Colorado’s death row. They will now each serve life sentences.

Efforts against the death penalty and against prison gerrymandering have each gained considerable momentum just over the past two years.

Colorado is the 22nd state to repeal the death penalty, and the third since the fall of 2018 (alongside New Hampshire and Washington). It’s also the eighth state to end or restrict prison gerrymandering, and the fourth just over the past year (alongside Nevada, New Jersey, and Washington).

—

Colorado has not executed anyone since 1997; it has been under a governor-imposed moratorium on executions since 2013.

Still, advocates say they fought to abolish the death penalty for this pause in executions to not depend on who the governor is. They also say abolition is important for death row appeals to not drain resources useful elsewhere, and for DAs to stop using the threat of a death sentence to pressure people into pleading guilty. Some DAs lobbied against the legislation on the grounds that they need to exert that sort of pressure.

Colorado’s reform also adds to the case that the U.S. is turning away from capital punishment. “We’re one piece of a much larger national conversation,” said David Sabados, the executive director of Coloradoans for Alternatives to the Death Penalty. “The country is one state closer to having a majority of states ban the practice.”

House Bill 100 was largely carried by Democrats. But it would not have passed the Senate without the support of GOP senators.

After the push to abolish the death penalty faltered in the Senate in 2019, state groups focused on persuading undecided senators. In January, the Denver Post reported that three GOP senators had swung to support abolition, virtually ensuring its success. One of them, Jack Tate, signed up as a prime sponsor alongside Democrats Jeni James Arndt, Adrienne Benavidez, and Julie Gonzales. (Owen Hill and Kevin Priola were the other Republicans to back repeal.)

Similarly, in New Hampshire last year, the legislature overrode the governor’s veto of a bill abolishing the death penalty when some GOP lawmakers joined Democrats.

Polis also offered clemency to all three people on death row in the state, Nathan Dunlap, Sir Mario Owens and Robert Ray. They will now serve sentences of life without the possibility of parole. “The commutations of these despicable and guilty individuals are consistent with the abolition of the death penalty in the State of Colorado, and consistent with the recognition that the death penalty cannot be, and never has been, administered equitably in the State of Colorado,” Polis said in a statement.

Commutations were necessary if Polis wanted to clear Colorado’s death row because the law he signed is not retroactive. It only repeals the option of the death penalty for offenses charged after July 1, 2020. More people could still be sentenced to death in the coming months given that the law only comes into effect in July; there are active cases where Colorado DAs are seeking the death penalty. But Polis’s actions today provide a hint of how he might handle future death sentences.

He had already signaled last year that he would issue commutations if the legislature voted to abolish the death penalty.

All three people who were on Colorado’s death row until today are African American men who went to the same high school, the Denver Post’s Alex Burness has pointed out. That’s in line with the racial gap and geographic disparities in who gets sentenced to death elsewhere in the country.

Two of those men were convicted of the 2005 murders of Vivian Wolfe and her fiancé Javad Marshall Fields, who is the son of Senator Rhonda Fields, a Democrat. Fields, who has long fought abolition, took a leading role again in opposing HB 100 when it was heard in the House in January.

—

Colorado is home to the county where the prison population represents the highest share of the overall population—Crowley County—according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

Prison gerrymandering has increased the power of areas like this where prisons are located. HB 1010 will end this practice in Colorado.

When the state next draws its maps, it will count incarcerated people at the place they last lived rather than at their prison’s location.

People in prison “have no real connection to their place of incarceration,” Kerry Tipper, a Democratic representative who sponsored the bill, told the Political Report in a written message. “In places like Colorado where you have big rural/urban divides, this is particularly striking. We are simply using people — moving their political power to a place they don’t want to be in and have no connection to.”

This law addresses congressional and legislative districts; counting people at their last place of residence will remain optional for some forms of local redistricting. But Aleks Kajstura, legal director of Prison Policy Initiative, said that “as a practical matter prison gerrymandering has been ended on all levels” since “county and school board districts are already required to avoid prison gerrymandering by statute” and “the municipalities that we looked at did the same on their own.”

Lawmakers from districts that house prisons resisted the reform. Those who represent Crowley County (Senator Larry Crowder and Representative Richard Holtorf) voted against it. So did Senator Jerry Sonnenberg, whose district contains four prisons, and Representative James Wilson; 6 percent of the people counted as living in Wilson’s district are in prison, Burness reported in the Colorado Independent. All four are Republicans.

Having a prison “in the community … affects the entire community,” Sonnenberg told Burness, so counting them elsewhere would “do an injustice to the communities that actually holds those prisons.”

The bill’s proponents reply that politicians from areas with prisons do not treat incarcerated people as constituents. “We spoke to several elected officials who represented large populations of incarcerated people and asked if they had ever held a town hall in a correctional facility,” Tipper and James Coleman, its lead sponsors, wrote in a Denver Post opinion article. “No one knew how many inmates were in their district, and only one had ever met with incarcerated individuals in their district.” The advocacy organization FAMM (Families Against Mandatory Minimums) has challenged lawmakers around the country to visit a prison.

Colorado is the eighth state to adopt a law against prison gerrymandering. Virginia’s legislature adopted a similar bill this session, and it now sits on the governor’s desk.

The clock is ticking for states to reform this issue by the next round of redistricting.

In changing where incarcerated people are counted, though, Colorado will still not count their voices. People in prison over a felony conviction won’t be allowed to vote, as is mostly the case in all states but Maine and Vermont. In 2019, Colorado restored the right to vote to all voting-age citizens not presently in prison. Taking the additional step of fully ending disenfranchisement in Colorado most likely requires a constitutional amendment and a referendum.

“I would support ending disenfranchisement,” said Tipper, calling it a “good thing for people to engage in their government and stay connected to their home communities. The average stay at DOC [the Department of Corrections] is 3 years. We want to ensure folks have something to go back to and staying (or getting) engaged in their community decision-making keeps people connected and motivated.”