Political Report

Clock is Ticking to Fix Prison Gerrymandering

With redistricting fast approaching, Nevada and Washington end prison gerrymandering, but reforms stall elsewhere.

Criminal justice reform in the states: Nevada and Washington end prison gerrymandering, but reforms stall elsewhere

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled last week that federal courts cannot stop partisan gerrymandering, which is the practice of drawing redistricting maps to favor one’s party. The decision has triggered calls for state-level reform, whether through litigation or institutional change.

But another redistricting practice that skews the geography of political power is still flying under the national radar: prison gerrymandering.

Most states count incarcerated people at their prison’s location rather than at their last address for purposes of redistricting. This inflates the power of the predominantly white and rural areas, where prisons are often located, at the expense of cities and communities of color, which suffer the brunt of mass incarceration. The skew is compounded by the fact that incarcerated people are barred from voting in all but two states, silenced even as their presence bolsters the representation of the areas they are displaced to.

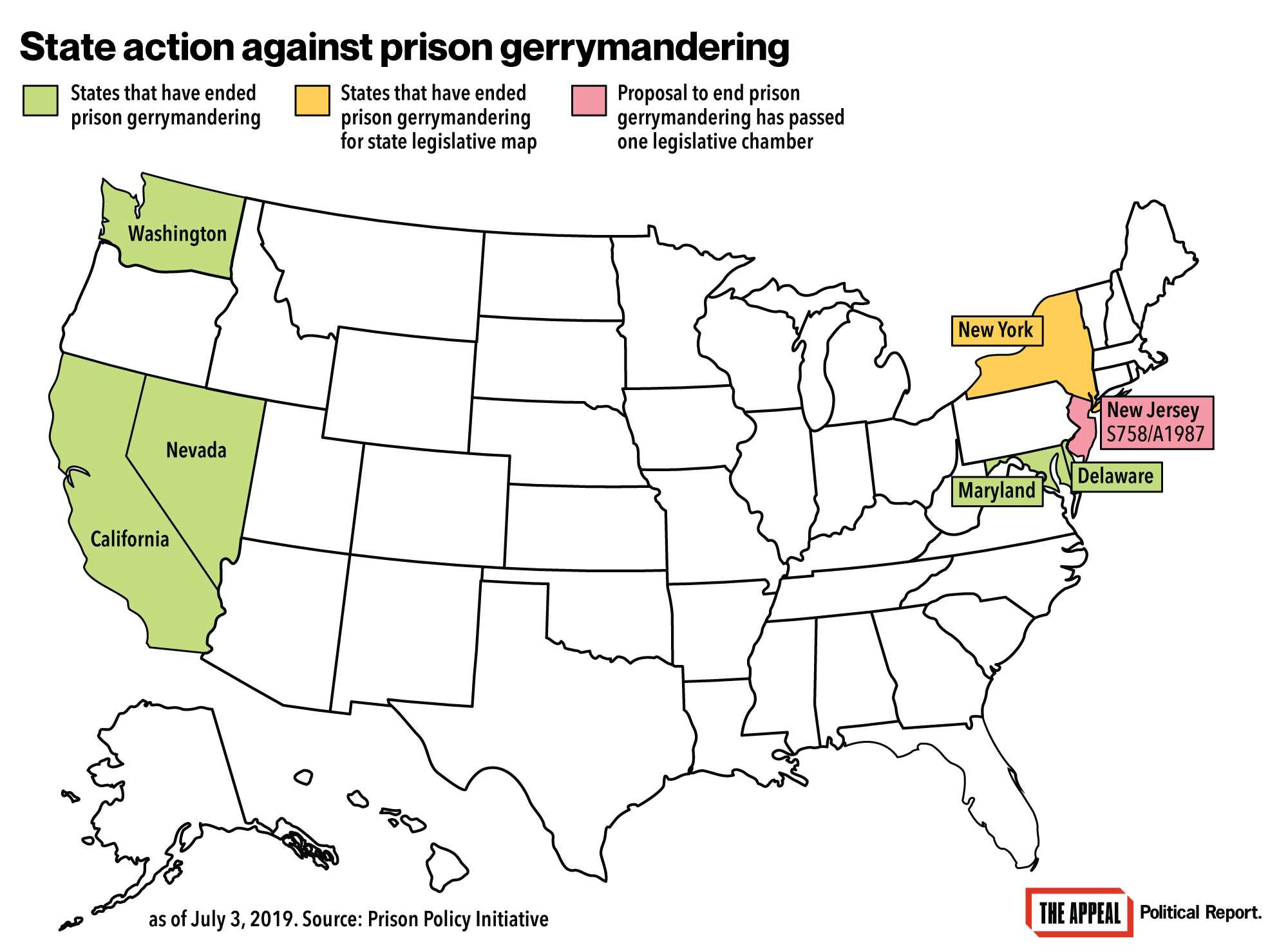

Nevada and Washington State both adopted legislation this year to end prison gerrymandering. In the next round of redistricting, they will count people at their last home address. Governors Steve Sisolak and Jay Inslee, both Democrats, signed these bills into law in May.

Three other states have ended prison gerrymandering: California, Delaware, and Maryland. New York has also done so for its legislative map, though not for its congressional one. These states will identify the home address of incarcerated people, adjust the Census Bureau’s count (which decided to keep counting people where they are incarcerated, despite pleas by advocates) accordingly, and in so doing determine the new population totals they will use in redistricting.

But this leaves 44 states that have not reformed their redistricting process. That includes Maine and Vermont, which enable incarcerated people to vote, but still engage in prison gerrymandering when redrawing their maps, according These states are about to once again gerrymander their maps by treating prisons as population centers.

The clock is ticking if states are to change this: The redistricting process begins in two years, and some states may need more time than others to collect the information they need to adjust the census count.

“There is still plenty of time left for states to pass reforms,” Aleks Kajstura, the legal director of the Prison Policy Initiative, an organization that has long worked on this issue, told the Political Report. “The particular cut-off for action will be unique to each state’s redistricting timeline; most should act by the end of 2020, while some may be able to pass reforms as late as 2021. That said, the sooner the better, particularly to allow for a smooth process for the transfer of data between the Department of Corrections and redistricting authorities.”

But many states chose inaction in 2019. Bills against prison gerrymandering were filed this year in Connecticut, Illinois, Oregon, and Rhode Island, but these legislatures all adjourned for the year without any of these proposals even making it out of one committee. There is an ongoing lawsuit filed by the NAACP against prison gerrymandering in Connecticut.

“Connecticut is dragged down by a sometimes insurmountable inertia, and we have to cut to that through that by bringing more voices to the legislature,” state Senator William Haskell, who supported this bill, told the Political Report. He added that some lawmakers make assumptions regarding what incarcerated people consider their residence, but are not willing to listen. “The problem when we talk about mass incarceration is that we can’t bring every voice to the [State] Capitol because many of them are behind bars.”

Another obstacle to reform is the political clout of legislators from areas that benefit from prison gerrymandering. “Some of the state’s most powerful lawmakers represent districts with prisons,” Oregon Public Broadcasting reported in May.

The best chance for another reform left this year lies in New Jersey, where the Senate passed a bill to end prison gerrymandering in February. But the reform has since languished in the Assembly’s State and Local Government Committee.

Assemblymember Vincent Mazzeo, chairperson of the committee, did not respond to a request for comment on whether the bill would receive a vote in the committee. Mazzeo voted for a similar bill in 2017, when the New Jersey legislature adopted it but then-Governor Chris Christie vetoed it.

Reforms to end prison gerrymandering are only one piece of the puzzle of ensuring democratic representation since, on their own, they still leave the people who are incarcerated disenfranchised. There are parallel efforts around the country to abolish felony disenfranchisement. Haskell introduced such a bill in Connecticut, but it also did not move forward this year. “Some legislators are unable to empathize with the formerly incarcerated or incarcerated because they don’t know anyone in that situation,” he said. “That underlies the need to bring those voices in the democratic process because we need their voices at the table, especially if some legislators aren’t willing to listen and empathize.”

In other legislative news on criminal justice reform:

Colorado: Colorado adopted a new law in May to restore people’s voting rights as soon as they are released from incarceration. The law came into effect this week. Most immediately, this means that the approximately 11,500 Coloradans currently on parole can now vote.

Louisiana: Governor John Bel Edwards signed into law a bill that shrinks DAs’ power to jail victims of sexual offenses or domestic violence to compel them to testify. The law prohibits such “material witness warrants” in misdemeanor cases; for felony cases, it imposes a list of conditions before someone can be detained. The law was narrowed from its original version, which banned detention altogether, in part because of the opposition of the head of the Louisiana District Attorneys Association.

New York: Efforts to legalize marijuana collapsed in the final day of New York’s legislative session. But the legislature adopted a backup bill, which Governor Andrew Cuomo has said he will sign. The legislation decriminalizes the possession of up to two ounces of marijuana (as opposed to one ounce previously), as well as the act of smoking marijuana in public. It reduces these acts, now misdemeanors, to a violation subject to a ticket and fine. In addition, the legislation provides for the automatic expungement of existing records: The state will vacate past convictions over offenses that are no longer deemed criminal.

You can follow the latest legislative developments in our interactive tracker.