Police Killed His Son. Prosecutors Charged The Teen’s Friends with His Murder.

It’s been four years since a Phoenix police officer killed Jacob Harris. Records obtained by The Appeal show officials have made inconsistent or false statements about the night police killed him. As Harris’s friends grow up behind bars, his father won’t stop until he gets justice for his son.

This story is published in collaboration with the Phoenix New Times.

Content warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of police violence and footage of police officers killing a 19-year-old.

Roland Harris has watched his son die a hundred times. The final moments of his life, documented in thermal video captured by a police aircraft, are burned into Harris’s mind: His teenage son, Jacob, steps out of a car. He runs from the police. Two seconds later, officers open fire. Bullets pierce his heart, lungs, and intestines. He falls to the ground, bleeding. Police pepper him with rubber bullets, hitting him in the face and backside. He is dying in the dirt. Then officers sic a dog on him.

It has been more than four years since a Phoenix police officer killed Jacob Harris, on January 11, 2019. The police department has since drawn a federal investigation into its use of deadly force. But Roland Harris’s fight for accountability has only left him with more questions: Why did police delete text messages from the night of his son’s shooting? Why are Jacob’s friends the only ones who have been held responsible for his death? How could anyone say his son’s killing was justified?

Harris’s search for answers has come at a significant cost: The cop who killed his son has demanded he pay the officer’s $40,000 attorney fees after a federal court dismissed Harris’s wrongful death suit. Harris and his wife split, in part, he says, because he became so deeply consumed by getting justice for his son.

“I have a void in my life that is never going to be filled,” Harris said. “Even when justice is served. It’s going to hit even harder. Because then I’ll have to focus on him not being here.”

Police have fought Harris every step of the way, refusing to disclose even basic information about his son’s death. It took six months for the department to release its report on the shooting, and even then, it only did so after he threatened to sue, Harris said. Police still have not returned his son’s belongings. But Roland Harris’s memories of Jacob remain fresh.

“He was all about family,” Harris said. “He helped me watch over his little sister, Leilani. He helped me coach little league basketball.”

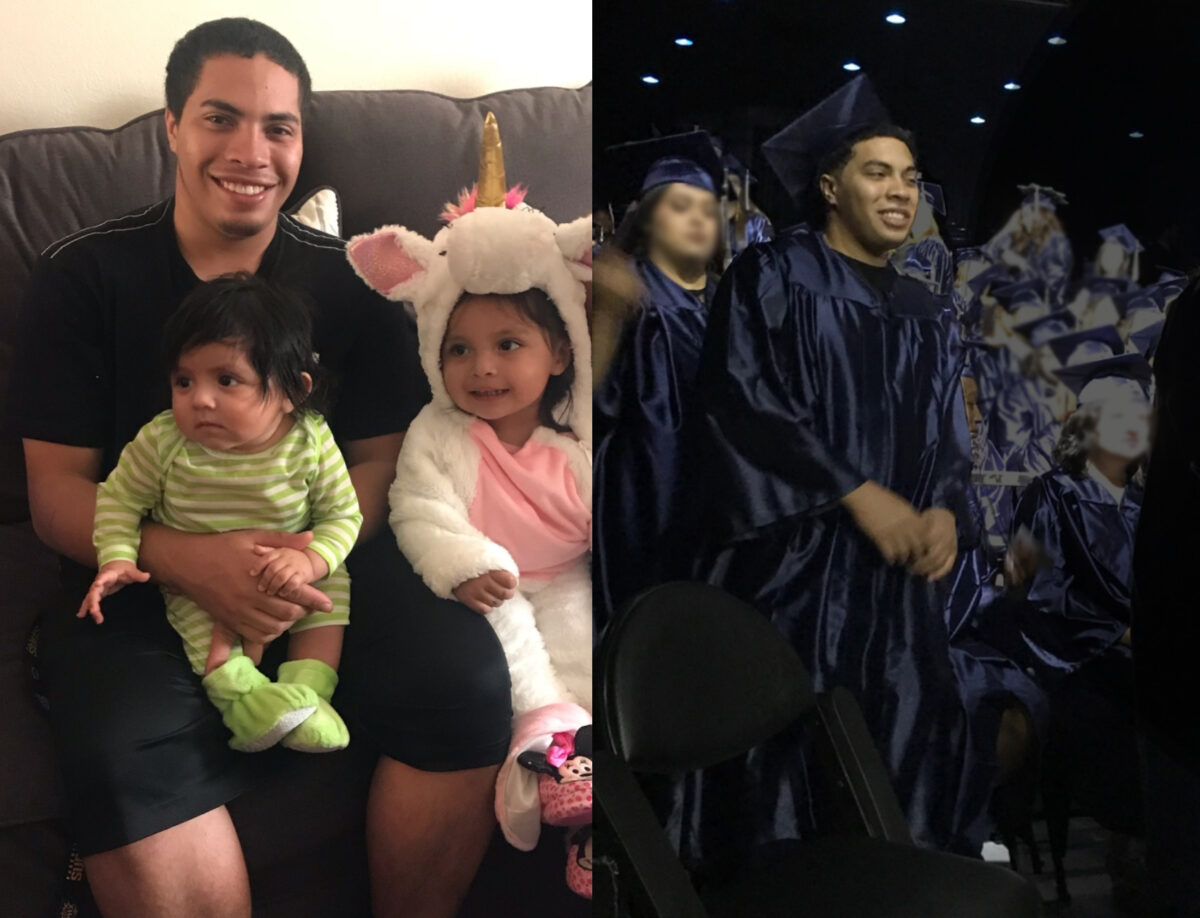

Jacob had wavy black hair and a big, bright smile, accentuated by the peach fuzz that had grown in above his lip and on his chin. He was on the shorter side—5 feet 4—and he had his dad’s broad shoulders and stocky build. He also had Roland Harris’s brown, almond-shaped eyes.

Harris said that when Jacob found out he was going to be a father at 16 years old, he got a full-time job, finished school, and helped to support his girlfriend and child.

Before long, Jacob and his girlfriend had another child. “Now his daughter will never know him,” Harris said. “His son will never know him. They will grow older. Those memories will fade. And they’re gonna forget him. All because of a trigger happy cop. His kids are never gonna get any father-daughter dances. He’s never gonna get a chance to walk his daughter down the aisle.”

Over the last few years, Harris has slowly uncovered more information about his son’s killing and the events that preceded it. But every answer brings new questions.

In an effort to piece together what happened on the night of Jacob Harris’s death, The Appeal reviewed more than 6,000 pages of records from official investigations into the shooting, the county attorney’s prosecution of Harris’s friends, and the civil suit Roland Harris filed against the city of Phoenix. The Appeal interviewed nine people involved with the case and also obtained police personnel records, transcripts of police radio traffic, and aerial surveillance footage of the shooting.

Prior to publication, The Appeal sent the Phoenix Police Department a detailed list of statements that would appear in this story. A spokesperson for the department did not answer any questions and offered only a brief response stating that the court had dismissed Harris’s suit.

“The case is now on appeal to the 9th Circuit court where you can find the court file,” the spokesperson wrote.

Law enforcement officials in Phoenix—including Kristopher Bertz, the officer who killed Jacob Harris—have justified the shooting by saying they feared Harris intended to shoot them. But records obtained by The Appeal show that multiple officials have made inconsistent or false statements about the circumstances surrounding the shooting. Even Bertz’s own accounts of that night have differed slightly. Aerial surveillance footage of the incident shows Harris running away. And a judge in the criminal case against Harris’s friends has stated unequivocally that Harris did not turn toward Bertz.

Police records also raise serious questions about the department’s conduct prior to the shooting. Officers had been surveilling Harris and his friends for over 12 hours at the time, believing them to be connected to a string of store robberies. Though police had many opportunities to stop the group throughout the day, they ultimately chose to sit by and watch a robbery occur. Police didn’t seek to apprehend Harris and his friends until after they drove away. But police never alerted the group to their presence or gave them a chance to pull over. Instead, officers escalated directly to a high-risk maneuver that forced the car to a stop. That’s when Harris ran out and was shot.

Despite these issues, the Phoenix Police Department investigated Bertz and determined that he acted in accordance with department policy in killing Harris. The Maricopa County Attorney’s Office declined to prosecute, stating that Bertz did not “commit any act that warrants criminal prosecution.”

Instead, prosecutors decided to hold Harris’s three friends responsible for his death. Arizona’s “felony murder” law allows people to be charged with murder if someone dies during the commission of a felony, even if they did not cause the death. Jeremiah Triplett, Sariah Busani, and Johnny Reed—ages 20, 19, and 14 at the time—were in the car with Harris on the night of his death. The Maricopa County Attorney’s Office charged them with first-degree murder, armed robbery, kidnapping, and burglary.

Busani and Triplett were held in jail on a $1 million bond for three years before finally being sentenced in the first few months of 2022. Busani was sentenced to 10 years in prison. Triplett was sentenced to 30 years. Reed was held on a $500,000 bond and was ultimately sentenced to 15 years in prison—more years than he had even been alive at the time of his arrest.

“You guys are taking my 14-year-old baby and signing his whole life off,” Reed’s aunt, Shawanna Chambers, said in an interview with The Appeal. Chambers raised Reed and his younger brother since they were babies. “He’s a young Black boy. And we’re in poverty,” Chambers said. “They were never going to hold the police accountable for Jacob’s murder. It was going to be us.”

Reed, who was in his first year of high school at the time of his arrest, has been incarcerated with adults for the last four years because of the seriousness of the charges against him, Chambers said. According to his aunt, he has spent some of that time in solitary confinement in an attempt to separate him from the rest of the prison population because of his age. For the last year, Reed’s family has been unable to talk to him except through email. Chambers said she applied to visit in person, but the department of corrections told her they never received her application. The Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation, and Reentry did not respond when contacted for this story.

“I honestly want people to know we made a mistake, but that should never define who our characters are,” said Reed in an email. “We ain’t kill Jacob, we watched Jacob die before our eyes, that was our friend.”

Prison has been a painful adjustment, Reed said. “I’ve had to overcome depression and all kinds of things. I’ve been locked up in Solitary Confinement a few times, and that takes a whole different toll on your conscience,” he said. “I really miss my family.”

Allowing a Robbery to Happen

Johnny Reed didn’t know police were watching him on the afternoon of January 10 as he stood outside his grandmother’s house with a group of friends. It was a warm, dry day in Glendale, a Phoenix suburb where the temperature rarely dips below 40 degrees. Reed was wearing navy jeans and a blue polo shirt buttoned all the way to the top. He had just finished the eighth grade the year before, but he’d grown lanky—already 5 feet 7 inches and very slight, just over 100 pounds. Police officers in unmarked vehicles snapped photos of Reed and his friends in front of the graying stucco walls of the Crystal Springs apartment complex. Ten thousand feet above him, a Phoenix police officer in a small airplane watched as the 14-year-old posed with an airsoft gun.

Reed had been spending a lot of time at his grandmother’s house after she was diagnosed with kidney failure. Reed was her first grandchild, and when she got sick, Reed would “never let her lift a finger,” said Chambers. His sweet and charming tendencies earned him the nickname “Butter” from his grandmother. It was a fitting term of endearment for a teenage boy who loved to bake. Chambers laughed over the phone as she recalled the many nights Reed and his brother spent in the kitchen, baking cookies and cakes. “I’d go to Goodwill and buy all this stuff that you could bake with,” Chambers said. “He couldn’t wait to get home and use them.”

To Chambers, Reed was a smart, easygoing kid who loved going to school and playing sports and had a positive influence on the people around him. “I want him home,” Chambers said over the phone, her voice breaking as she discussed what it had been like to see the child she had raised imprisoned for the last four years—with at least eight more to go. “We need him. They threw him away, he doesn’t mean anything to them. He means so much to us,” she said through tears.

Police were watching Reed and his friends because they believed that at least one of them—Jeremiah Triplett—was involved in a string of armed robberies that had taken place at fast food restaurants and convenience stores across the county over the previous two months. As is standard procedure in robbery investigations, Detective Jacob Rasmussen reviewed armed robbery reports, looking for patterns. Eventually he strung together several reports involving young Black males of similar builds, with hoodies cinched up around their faces. According to Rasmussen, these robberies often occurred at places like Whataburger fast food restaurants and Circle K convenience stores, and they often involved suspects who brandished a gun and took money from the cash register. Sometimes they took cigarettes. Some reports mentioned a red or maroon vehicle. But police didn’t have names or license plates.

Rasmussen asked other police departments in Maricopa County to look for similar robbery cases. On January 9, 2019, the Glendale Police Department passed one along. Four months earlier, Triplett had been arrested in connection with two robberies at Circle Ks. A Glendale patrol officer spotted Triplett in the parking lot of another Circle K on September 8, 2018, and recognized him from surveillance footage of the robberies that had occurred two days prior. Triplett left the parking lot driving a car with expired plates. Police pulled Triplett over and found Newport cigarettes and a bottle of Hennessy liquor in the car, the same items taken in the recent robbery. Triplett was arrested and pleaded guilty to solicitation of robbery. He was ordered to pay restitution and sentenced to 30 days in jail and three years of probation.

The Glendale police report shows why Phoenix police thought Triplett might be connected to the string of robberies Rasmussen had identified. But the thousands of pages of records The Appeal reviewed for this story do not explicitly state why surveillance began, or who, if anyone, police surveilled besides Triplett.

Neither the Phoenix Police Department nor Rasmussen responded when asked why they started surveilling the group on January 10.

Despite having at least nine police reports and surveillance videos of similar robberies, some of which involved a red or maroon SUV, police say they had no choice but to watch a robbery unfold in order to make an arrest.

A decision was made “to allow a robbery to happen,” Bertz said during a 2021 deposition for the civil case Roland Harris filed against the city. “That planning aspect was deemed, to my understanding, based on the fact that we did not have probable cause or sufficient evidence at the moment before the robbery to effect an actual arrest.”

Two other officers also said in depositions that the police department’s plan that evening was to allow a robbery to occur because “the investigators felt they didn’t have enough probable cause to make an arrest” for any of the more than two dozen prior robberies police believed the group had been involved in.

But during the 12 hours police spent surveilling Triplett and others, officers witnessed multiple crimes take place long before the group robbed a Whataburger. Police saw Triplett, who they knew already had a felony conviction, in possession of a gun—an offense he was later charged with. They saw Reed, a child, in possession of what they believed at the time was a deadly weapon. (It was an airsoft gun.) And they saw Triplett, who police knew was just 20 years old, drinking alcohol. Police surveillance photos of Triplett show a tall young man with dark hair and the beginnings of a beard. He was wearing a black, long-sleeve Champion shirt and a gold chain when officers secretly photographed him outside his mother’s house.

There were plenty of other opportunities to make an arrest, said Triplett’s mother, Theresa Greene, who lived in the same apartment complex as Reed’s grandmother. “I don’t know what was going through their heads, but now it’s cost a person their life.”

Instead, just after midnight on January 11, police watched and waited as a 14-year-old boy crawled through the drive-thru window of a burger restaurant and brandished an airsoft gun at the employees inside.

“Let People See What Police Really Did to Him.”

Two minutes after entering the Whataburger, Triplett, Reed, and Harris ran out of the restaurant and jumped into a red 2001 Honda Passport SUV driven by Sariah Busani. Busani had just turned 19. She had moved back to Phoenix a few months earlier after spending the summer with her mother, Christina Gonzales, in Parker, a town of about 3,000 people a few hours northwest of Phoenix, along the Colorado River. Busani had always been striking, her mother said, with a mane of long, dark hair, bright hazel eyes, and a petite frame. “She’s a beautiful person,” Gonzales said. “She’s the center of attention. Everybody loves Sariah. People are just drawn to her.”

Gonzales missed much of her youngest daughter’s childhood because she was struggling with substance use at the time and gave her parents custody of her children. Busani’s father had been in prison when she was a baby and was deported back to Mexico when he was released. To Gonzales, it was a dream to spend that much time with her daughter after all they had been through.

“We’d wake up in the morning and go down to the river,” Gonzales recalled. “We’d walk to this little market in the mornings. We’d always get the same thing—hot Cheetos and a soda. She’d talk to me about boys. One time in the living room we were just being goofy, rolling around tickling each other. We were laughing so hard, we couldn’t stop laughing. She was getting me, I was getting her. That’s my best memory,” Gonzales said as she began to cry. “I didn’t want her to leave.”

Gonzales wonders if she could have stopped what happened to her daughter if she hadn’t let her return to Phoenix. “Maybe if I would have done it differently,” Gonzales paused, choking back tears. “She would be here, you know?”

On January 11, Busani pulled out of the Whataburger parking lot with Triplett, Reed, and Harris in tow, unaware of the police surveillance plane tracking them from above. Footage taken from the aircraft shows unmarked police cars following Busani’s vehicle for nine minutes as the group drove down 10 miles of desert highway. There are no lights or sirens. At no point do police officers identify themselves or give Busani an opportunity to pull over.

Busani stops at a red light. The light turns green, and she accelerates. That’s when Officer David Norman pulls up to the rear of the Passport and deploys a device known as The Grappler to seize the back left tire of the vehicle. The department had recently acquired the tool, a heavy-duty nylon tether that latches onto a car’s axle. It was Norman’s first time using it outside of training.

The SUV jerks to a stop, turning slightly left from the force. A wall of unmarked police cars close in on the incapacitated vehicle. Officer Bertz puts his cruiser into park, opens the door, and throws a flashbang toward the passenger side of the Passport. It explodes and covers the area with a blinding light.

In the chaos, Jacob Harris opens the rear passenger door of the Passport and takes off running away from police. Within two seconds, officers gun him down. In total, Bertz, armed with an AR-15-style assault rifle and Norman, armed with a handgun, fire 11 shots at Harris. He is struck twice in the back. The first bullet penetrates his heart and his right lung and fractures his ribs, according to the medical examiner’s report, which would rule Harris’s death a homicide. The second tears through his gallbladder and intestines. Bertz fired both of the fatal shots.

The aerial surveillance footage shows Harris fall to the ground as he is shot, his arms extended above his head. A small object flies from his hands as he falls. Police would later report finding a gun on the side of the road where Harris was shot. Triplett and the two teenagers remain in the vehicle while other officers shoot out the windows of the Passport with rubber bullets. Terrified, Busani curls into a ball on the car’s floor with her hands held above her head.

“It all happened so quick,” Busani said. “Honestly it could have been any of us that night. I thank God every day because anything bad could have happened. We could have crashed, we could have all died.”

Content warning: The following paragraphs contain a graphic description of police violence and the death of a teenage boy. We are publishing video footage of Jacob Harris’s death at his father’s request. Click here if you would like to skip the section that contains graphic details.

As Harris lies bleeding face down on the ground, police shout commands at him. Harris puts his hands to his head. Police tell him not to move. Harris, who at this point is mortally wounded, can be seen in the aerial footage wiggling his legs. Moments later, a Phoenix police officer shoots Harris in the backside with a rubber bullet. Harris recoils from the blow but remains on the ground.

Some officers stay trained on Harris, while others order Triplett and the teenagers out of the vehicle one at a time and forcefully detain them. Officers shoot Harris with another rubber bullet, this time in the face. The force of it flips Harris onto his side. He clutches at his chest and curls into the fetal position. Then police sic a dog on him.

The dog bites Harris’s leg, thrashing its head from side to side as it drags Harris back toward the officers. They handcuff the dying teenager. At least 10 minutes pass from the time police shoot Harris to when officers render aid.

The Phoenix police report on the shooting states that two officers cut off Harris’s clothing and put pressure on his wounds. Harris kicked his feet and tossed his head in pain. The fire department came and transported Harris to a hospital nine miles away.

At 1:05 a.m.—43 minutes after Bertz and Norman opened fire—Harris was pronounced dead.

Phoenix police charged Harris with aggravated assault on a police officer. In the report on Harris’s death, Bertz and Norman are listed as “aggravated assault victim[s].” The charges were later dropped in light of Harris’s death.

“A Black 19-year-old child’s life is worth nothing to the city of Phoenix,” said Roland Harris, Jacob’s father. “Let people see what police really did to him. It was murder. It was a shooting and then they tortured Jacob afterwards.”

The city of Phoenix has long maintained that Harris’s death was justified, but multiple law enforcement officials have made inconsistent or false statements about the circumstances surrounding his death. In a press release sent to reporters shortly after the shooting, a spokesperson for the Phoenix Police Department said Harris “pointed his gun in the direction of officers.” But in an interview with the department’s professional standards bureau following the incident, Bertz himself said this did not happen.

When introducing the case against Harris’s friends to a grand jury, Heather Kirka, a prosecutor with the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office, said Harris “exchanged gunfire” with police. But Phoenix police officers who investigated the crime scene after the shooting found no rounds in the chamber of the handgun that was said to belong to Harris and no casings matching that firearm.

Bertz and Norman have said Harris turned toward Bertz while holding a gun, though Bertz’s statements about that night have not been consistent.

In an interview immediately after the shooting, Bertz told police investigators that he saw Harris get out of the car with a gun in his right hand. According to Bertz, Harris looks at him, starts running, then “turns back towards me just slightly, kinda makes a deliberate movement with that gun.” Then he shoots Harris.

Almost a month later, during an interview with the department’s professional standards bureau, Bertz described it differently. He said Harris exited the vehicle with a gun in his hand, then stopped. “He had a gun, stopped his motion of fleeing, made a deliberate movement with his arm looking back in my direction,” Bertz said. Later in that same interview, Bertz said it was just Harris’s arm that stopped moving, and that what he actually meant was that Harris was running with his arm held still against his chest. When asked about this apparent discrepancy during his deposition in the civil case brought by Harris’s father, Bertz said, “I was not trying to describe that he, Jacob Harris, the entirety of his person stopped, but that my focus being that the gun, the arm, and the hand holding the gun was not simply trying to—to run at that moment.”

During the professional standards bureau interview, Bertz was asked directly if the gun was ever pointed at him. “No it never got fully up on me,” he responded. But during his deposition, Bertz said: “When that back rear passenger door opens, the first thing that presents itself from that door is a semiautomatic firearm being held in the right hand of the occupant seated or now exiting the backseat of that vehicle. That firearm comes out of the vehicle and swings back towards my direction where I’m at, which is again off to the south and west of where their final stop location was … As that subject gets out and I identify that weapon being pointed back towards me, I raised my rifle.”

Of the eight officers who were present at the time of the shooting and provided official statements, only two—Norman and Bertz—said they saw Harris holding a gun. They are also the only ones who reported seeing Harris turn toward Bertz. In Norman’s deposition and his interview with police investigators immediately after the shooting, he said Harris was running away from them, but turned back toward Bertz twice—all in the matter of two seconds. Another officer, Charles Holton, said he only saw Harris run and couldn’t see his hands.

Video of the killing taken from the police aircraft shows Harris running away. He does not stop. He does not turn. He does not extend his arm toward police. And he never exchanges gunfire with the police, as prosecutors first told the public. Police and prosecutors have said the footage shows Harris as a “white blob,” and that the thermal camera inside the airplane does not capture “individualized movements.”

But the footage itself clearly shows the delineation of Harris’s arms and hands. The video appears to show Harris fleeing for two seconds, before he is felled by a hail of gunfire. His arms and hands extend in front of him when he is shot.

“You can’t justify shooting my son twice in the back while he was running away,” Roland Harris said. “Justify why you shot my son in his ass with a beanbag gun after he had already been shot through the lung and the heart. Justify that to me. Justify you telling my son to obey a lawful command and get up and then you shoot him in his fucking face with a beanbag gun, and then sic a dog on him. Justify why your other officers on the scene allowed that to happen.”

Nothing to Hide

Roland Harris has been given plenty of reason to be suspicious about the official narrative that night. Police and prosecutors have repeatedly made inconsistent or misleading statements about his son’s death. His attorneys were never able to depose the crime scene analyst from that night, Jennifer DiPonzio, though they had plenty of questions only she could answer. And transcripts of police radio traffic show that officers were communicating on an encrypted messaging platform on the night Jacob Harris was killed—but those messages have since been deleted.

In his deposition, Bertz confirmed that he and other members of his squad had used the messaging platform WhatsApp to share updates and information that night.

Communications between government employees are public records, and they are required by law to be preserved and disclosed in lawsuits or public records requests. But Bertz said he deleted his WhatsApp communications from that night.

“Do I possess them or did I possess them at this time, no,” Bertz said of the messages during his deposition. He said that after lead investigators took their notes on the case, he did not believe he was required to save the messages.

Bertz said he deleted the records before being notified of Roland Harris’s intention to sue, as a matter of standard practice to clear clutter from his phone. “My basis for understanding was that we weren’t responsible for maintaining those [messages] in the immediate aftermath,” he added.

Bertz said the messages would have contained surveillance photos that police were sharing or dropped pins to share vehicle locations. He said the messages were not an ongoing dialogue about the plan of action for that evening, as those conversations would have happened over the radio, on the phone, or in person.

Harris’s attorneys filed a motion in court asking Bertz to produce all documents in his possession related to the shooting of his son, including any text messages. But in his deposition, Bertz said he deleted the messages months before.

“If they had nothing to hide, why did they delete the WhatsApp messages?” Harris said.

Harris says the messages could have contained crucial evidence pertaining to his son’s death.

“They could have been coordinating their stories,” Harris said. Or maybe they were “talking about what they’re gonna do, what the game plan is. If somebody gets out, shoot ’em. We’ll never know.”

Norman, Bertz, and the attorney representing Bertz and the city of Phoenix in Harris’s lawsuit were all provided with a detailed list of statements that would appear in this story and requests for comment prior to publication. None responded.

In his deposition, Norman, who was not a member of the squad that was using WhatsApp that night, said he did not talk to Bertz in the aftermath of the shooting. After a police shooting, the officers involved “are now sort of sequestered,” Norman said. “We know not to start talking about the incident. We have to wait for investigators and wait for union reps and all that stuff.”

On the night of the shooting, command staff on the scene immediately asked to see the footage captured by aircraft surveillance—something that Brent Bundy, one of the officers in the aircraft, said was unusual.

During his deposition in Roland Harris’s civil suit against the city, Bundy is asked how many times in his 20-year career supervisors have asked to see aerial video at the scene. “Off the top of my head, two to three, three or four times, maybe, at most,” Bundy responds, “It’s a very, very small number. It’s a very rare circumstance where they would request the video actually immediately at that time.” Bundy later said the air surveillance unit “may have sent them a copy” of the footage that evening.

In a different deposition, Anthony Winter, the Phoenix police officer responsible for investigating the Jacob Harris shooting, confirmed that a copy of the footage was brought to the scene.

The lack of transparency has made Harris question whether his son was actually armed at the time of his shooting, or whether “the object that flew out of Jacob’s hand was a cell phone,” he said. In the police report on Jacob Harris’s death, several officers stated that they saw a gun on the ground a short distance away from the area where he was shot.

Ultimately, the Phoenix Police Department’s investigation into its own officers determined that Bertz and Norman had acted in accordance with department policy when they shot at and killed Harris. The Maricopa County Attorney’s Office declined to bring charges against either officer, stating that “the officers did not commit any act that warrants criminal prosecution.”

Instead, the county attorney’s office determined that it was Harris’s friends who should be punished for his murder.

“I cry at night just thinking about it all.”

Reed, Busani, and Triplett have been behind bars since the night of Harris’s killing. Unable to afford the high bails set for them, they spent three years in jail before pleading guilty and being sentenced to prison last year.

On January 17, 2019, six days after police killed Harris, prosecutor Heather Kirka presented the case to a grand jury, seeking to indict the teens and Triplett for first-degree murder, armed robbery, kidnapping, and burglary. Prosecutors brought in Rasmussen, the lead investigator on the robbery case, as their only witness. Neither Kirka nor Rasmussen responded when contacted for this story.

Rasmussen is not mentioned in official reports as being present at the time of Harris’s shooting. But he nonetheless told jurors that as Harris ran, he “turns, points the gun at [Bertz and Norman], at which time both of these officers discharge their weapons.” Later, when Rasmussen was asked how many shots were fired from the officers’ weapon, Rasmussen responded, “there were two shots fired from a handgun and a rifle by officers.” The Phoenix Police Department’s own investigation shows that Norman and Bertz fired 11 shots at Harris.

Based on Rasmussen’s statements, the grand jury indicted Reed, Triplett, and Busani on all charges. But Judge Suzanne Cohen sent the case back to a grand jury six months later because of a “factual discrepancy” in Rasmussen’s testimony, according to transcripts obtained by The Appeal.

“[T]he detective does testify [Harris] has a gun in his hand as he gets out and as he is running he turns and points the gun at them,” Cohen says in the transcripts.

“That did not happen,” Cohen concludes. “He did not turn as he was running and point the gun. His body is going in one direction and one direction only.”

In July 2019, prosecutor Joshua Maxwell presented the case to a grand jury for the second time. Busani’s defense attorney, Adrian Little, argued that the second grand jury proceedings were also misleading because Maxwell and Rasmussen repeatedly told jurors that Harris turned back toward Bertz as he ran away, despite the fact that the court had already rejected this characterization.

Ultimately, Cohen decided that Maxwell and Rasmussen “did not intentionally present false or misleading testimony to the Grand Jury.” She concluded that Rasmussen had simply told jurors what officers Bertz and Norman said they saw. Furthermore, prosecutors allowed jurors to view the aerial surveillance footage during the second presentation. Maxwell did not respond when contacted for this story.

On July 16, a grand jury again indicted Busani, Reed, and Triplett on all charges, including first-degree murder. The vote was 9-5.

As the cases against the trio moved forward, prosecutors took steps to ensure that they faced the most severe consequences possible. The charges against Busani, Reed, and Triplett were treated as dangerous felonies because, prosecutors said, they “involved the discharge, use, or threatening exhibition of a handgun, a deadly weapon or dangerous instrument.” Arizona law requires harsher penalties and more prison time for felonies classified as dangerous.

Prosecutors also alleged nine aggravating circumstances against Busani, 16 against Triplett, and 10 against Reed, including calling the 14-year-old a “danger to society.” Aggravating circumstances, such as involving an accomplice, damaging property, or having prior convictions, also lead to harsher criminal penalties and longer prison sentences under Arizona law.

At one point, another prosecutor on the case, Mitch Rand, stated that Busani was facing 75 years in prison if convicted. But Rand also argued that should the case go to trial, the jury should not be allowed to know the possible sentences Busani, Reed, and Triplett faced, because that could make jurors less willing to convict them. Rand did not respond when contacted for this story.

In October 2019, while Triplett was in jail awaiting trial, his 2-year-old son wandered into a pond near his mother’s apartment complex and drowned. After learning that his child had died, the jail placed Triplett on suicide watch. While incarcerated, Triplett also missed the birth of his second child.

“I cry at night just thinking about it all,” Triplett said. “I am away from my family, my daughter like I never got to hold her. I didn’t get the chance to see her be born.”

Then, in December 2019, prosecutors brought a separate 128-count indictment against the trio for their alleged involvement in a string of robberies that took place from November 2018 through January 2019.

Prosecutors charged Busani with conspiracy to commit robbery, illegal control of an enterprise, and theft. They hit Reed with the same charges, plus eight counts of armed robbery, 22 counts of kidnapping, and 16 counts of aggravated assault. Prosecutors alleged that each person who was inside the establishments when the robberies occurred was kidnapped. The “aggravated assault” charges stem from Reed or Triplett “using a simulated handgun, a simulated deadly weapon” to place store employees “in reasonable apprehension of imminent physical injury.” Busani, Reed, and Triplett were not accused of actually physically harming people, though victims did tell the court they feared for their lives and suffered from anxiety and panic attacks after being held at gunpoint. Triplett was charged with conspiracy to commit armed robbery, theft, and eight counts of illegal control of an enterprise, 37 counts of armed robbery, 37 counts of kidnapping, and 40 counts of aggravated assault.

In a statement shared with The Appeal, a spokesperson for the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office said prosecutors had “carefully considered the mitigating and aggravating factors for each defendant’s plea agreement” and “acted with integrity to seek justice for the more than 50 individuals and 25 business victims in these matters.”

In his testimony to a grand jury regarding the robbery case, Detective Rasmussen explained that he had reviewed reports of armed robberies at fast food restaurants and convenience stores for similarities. Eventually he found several cases that involved people of color with similar builds wearing hoodies cinched up around their faces using a gun to take money from Circle Ks and Whataburgers.

On January 11, hours after police killed Jacob Harris, officers served search warrants on the homes of Harris, Reed, and Triplett, where they said they found clothing, shoes, and accessories that matched what suspects in the other robberies were seen wearing on surveillance footage.

Theresa Greene, Triplett’s mother; Shawanna Chambers, Reed’s aunt; and Roland Harris all say that the searches were conducted while the families were not home, and before police had informed them of the shooting and the arrests of their children.

When Roland Harris walked out of his apartment that morning to drop his daughter off at school, he said he saw police cars blocking in his son’s Mazda. Though his son had already been dead for several hours, police did not say anything to Harris at that time. Instead, while Harris went to work, police raided his home, where he lived with Jacob. They took his son’s shoes, his clothes, his IDs, and his jewelry. They also took Roland Harris’s laptop, two watches, and $800 in cash. And they took Roland’s daughter’s iPads and a shoebox with her name on it that she stored money in.

Only after that did police go to Roland Harris’s workplace to tell him his son was dead. Harris said Rasmussen first made it sound like Jacob’s friends had killed him.

“I lost it,” Harris said. “He was like, ‘Rest assured and find solace that they’re gonna pay for his murder.’”

A short time later, a different detective told Harris that his son had been involved in armed robberies, and said he was shot after pointing a gun at police officers.

“I told him he was a liar, you guys murdered my son,” Harris said.

Greene was in physical therapy that morning when she got a call from a friend telling her that someone had broken into her home and that her door was wide open. “I called the police,” she recounted. “The Glendale police came out, said Phoenix police had raided my house. I said why didn’t they just knock on the door? They really had to break the door in? All they had to do was ask for the keys from management, they had a warrant. They completely ransacked my whole house. They turned off all of my surveillance cameras. I felt so violated and angry.”

When police showed up to search Reed’s grandmother’s home, Reed had already been in custody for hours. Officers made no attempt to obtain consent before conducting a raid, according to Chambers. With her terminally ill mother still inside and in a wheelchair, officers threw a smoke bomb into the home, tore the door off, and pillaged the house, Chambers said.

“My mom died a few months later,” Chambers said. “Johnny was her favorite. She couldn’t last any longer.”

“I wasn’t able to protect him.”

With Reed, Triplett, and Busani already facing the possibility of decades in prison for Harris’s murder, prosecutors leveraged the robbery indictment to extract a plea.

“We were all backed into a corner,” said Chambers. “Do we take 15 years or do we take life? The prosecutors said this is the only plea deal we’re going to give you. If you go to trial with this you’re going to get life.”

In the end, all three pleaded guilty, rather than risk life in prison. Busani was sentenced to a total of 10 years in prison, Reed to 15 years, and Triplett to 30 years. Triplett’s long incarceration is especially risky because he has a serious brain condition that will most likely require future surgeries—and prison healthcare in Arizona is notoriously bad.

Triplett has had at least six brain surgeries to treat hydrocephalus—a buildup of cerebrospinal fluids that exerts pressure on the brain, which can cause brain damage, vomiting, changes in personality, and severe headaches. Triplett had a shunt implanted in his brain to drain the excess fluid when he was a baby, Greene said. The shunt runs down his body and drains into his stomach, where the cerebrospinal fluid is absorbed.

“He has really bad migraines,” Greene said, adding that she has tried to get her son medical help in prison but has been unable to. “It was to the point where he’d be vomiting, he can’t eat, can’t be around light or sound.”

While Triplett, Reed, and Busani were being prosecuted for Harris’s death, his father advocated on their behalf.

“We all lost our children,” Chambers said. “But Roland will never see his son again. He pleaded for each and every one of them for the judge to give them leniency.”

Harris attended “every single one of Sariah’s court dates,” said Christina Gonzales, Busani’s mother, calling him “a godsend.”

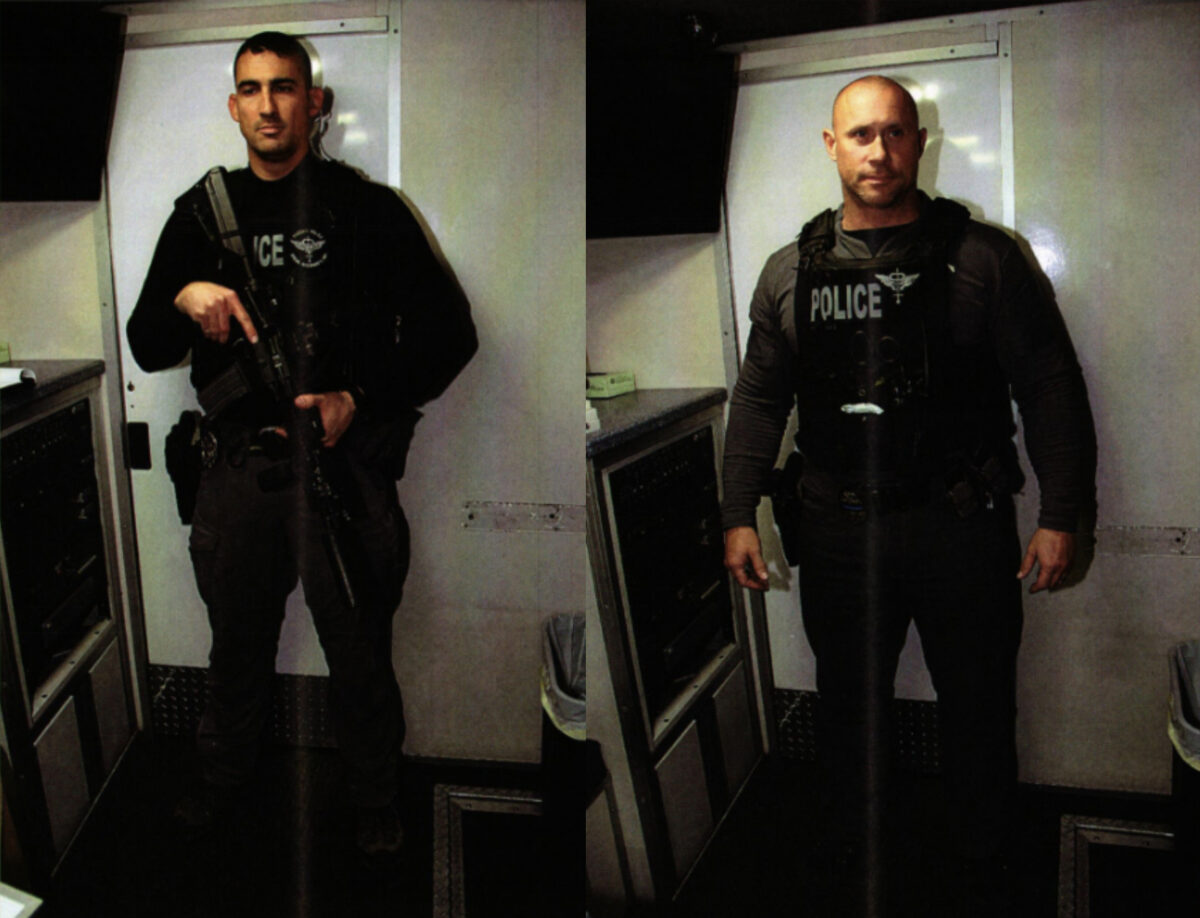

Harris believes the officer who killed his son should have been prosecuted—not Reed, Triplett, and Busani. Bertz, 37, is still working for the Phoenix Police Department collecting about $90,000 a year from taxpayers.

Norman, 50, has retired, but he still draws more than $5,000 each month from his pension from the city and now runs a law enforcement training company called TruKinetics. He is also a contractor with the Department of Defense, according to his deposition.

“They’re sitting there, going on with their lives, opening up businesses,” Harris said. “They don’t think about the wreckage that they left behind. Father’s Days are never the same. I don’t even celebrate it. It hurts so much.”

Jacob Harris is not the only person Bertz has killed. According to a database of statewide police shootings created by The Arizona Republic, Bertz shot and killed 38-year-old Erik Pamias in 2017. In 2021, two years after killing Harris, Bertz shot another person, 34-year-old Dustin Weaver. Bertz said Weaver pointed a gun at him, though his body-worn camera wasn’t activated until after he shot Weaver. Weaver survived and was sentenced to seven years in prison for aggravated assault.

Bertz did not respond to emails from The Appeal regarding his involvement in the Jacob Harris killing or his other on-duty shootings.

Norman also has a history of violence. In 2014, he killed 26-year-old Craig Uran. According to police, Uran had stolen a truck and pointed a gun at officers. Uran’s girlfriend, 23-year-old Jessica Hicks, was in the passenger seat. Norman shot Uran in the head with an assault rifle as he attempted to flee. Uran’s girlfriend was charged with his murder. She spent two years in jail awaiting trial before ultimately pleading guilty to auto theft and armed robbery. She was sentenced to five years in prison.

Before retiring, Norman shot at so many people in a single year that it prompted an automatic alert to his supervisor. In March 2018, Norman shot and killed 44-year-old Stephen Hudak after Hudak shot another officer. Three months later, he shot at 30-year-old Stephen Harris, who survived.

“I was a fucking savage. I really sought these events. I wanted these experiences. I was super aggressive,” Norman said on a July 2021 episode of “Blue Line Millennial,” a law enforcement podcast. “The majority of my career, you get an officer-involved shooting and get three days off … So you kind of hope it’s on your Friday.”

Norman did not respond to emails from The Appeal regarding his involvement in the Harris shooting or his statements on the podcast.

Roland Harris is still fighting to get justice for his son. A federal judge ultimately dismissed his civil lawsuit against Bertz, because Arizona law allows police officers to use deadly force when they believe it is necessary to prevent the escape of a person who the officer believes had committed a felony with a deadly weapon. After the judge dismissed the case, Bertz filed a motion in court attempting to force Harris to pay for his attorney’s fees.

Harris is appealing the judge’s decision to dismiss the lawsuit. He has also met with Department of Justice officials investigating the Phoenix Police Department and shared with them the video of his son being killed. Harris said the investigators were emotional when they watched the footage and told him they would pass the information along to the DOJ’s criminal division.

Phoenix police officers have killed at least 142 people since 2013, according to Mapping Police Violence’s database. None of those officers were charged.

As Harris enters his fifth year of fighting, he is still exasperated by the refusal of police, prosecutors, or any official, to acknowledge what he sees as the basic truth: “They didn’t have to shoot my son down like a dog in the street.”

He also acknowledges that the ordeal has changed him.

“I am definitely not the same person anymore. A lot of my friends notice that. I’ve got a lot of anger in me,” he said. “You’re a father, you’re supposed to be your child’s protector, and I wasn’t able to protect him.”

But Harris is determined to keep going. He couldn’t sleep at night, he says, if he knew he wasn’t doing everything he could for Jacob.

“I don’t want another parent to feel what I feel,” Harris said. “I will not stop. For the rest of my life, as long as I’m breathing air, I will stay on them. There is no statute of limitations on murder. Until the day I die. I will not stop until my son gets justice.”