Pennsylvania Mandatory Minimum Bill Is Unlikely to Reduce Gun Violence, Opponents Say

State Representative Todd Stephens has introduced a bill to impose a five-year minimum prison sentence for illegally possessing a firearm, but the governor, advocates, and others say it’s the wrong approach.

A bill introduced in September in the Pennsylvania General Assembly would ratchet up the penalties for people convicted of certain gun crimes.

House Bill 1851, which aims to curb gun violence, would require that anyone convicted of possession of a firearm by a prohibited person—someone convicted of a felony, for example, or involuntarily committed to a mental health institution—serve a five-year mandatory minimum prison sentence. Had the proposal been in effect in 2018, more than 30 percent of people convicted of this offense would have seen their sentence increase by at least three years, according to data published by Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing.

The state House of Representatives could vote as soon as early February on HB 1851, which would then go to the Senate if approved.

Some advocates and public officials oppose the bill, saying harsher sentences will not curb gun violence. “We have decades of research showing that mandatory minimum sentences are ineffective and counterproductive responses to gun violence,” Celeste Trusty, Pennsylvania state policy director at FAMM (Families Against Mandatory Minimums), told The Appeal.

In 2015, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court effectively struck down mandatory minimum sentences in the state. The court relied on a 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision that said any elements that might trigger a mandatory minimum—like possessing a firearm in the commission of a crime—must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt in order to impose that minimum. HB 1851 includes language meant to comply with those rulings.

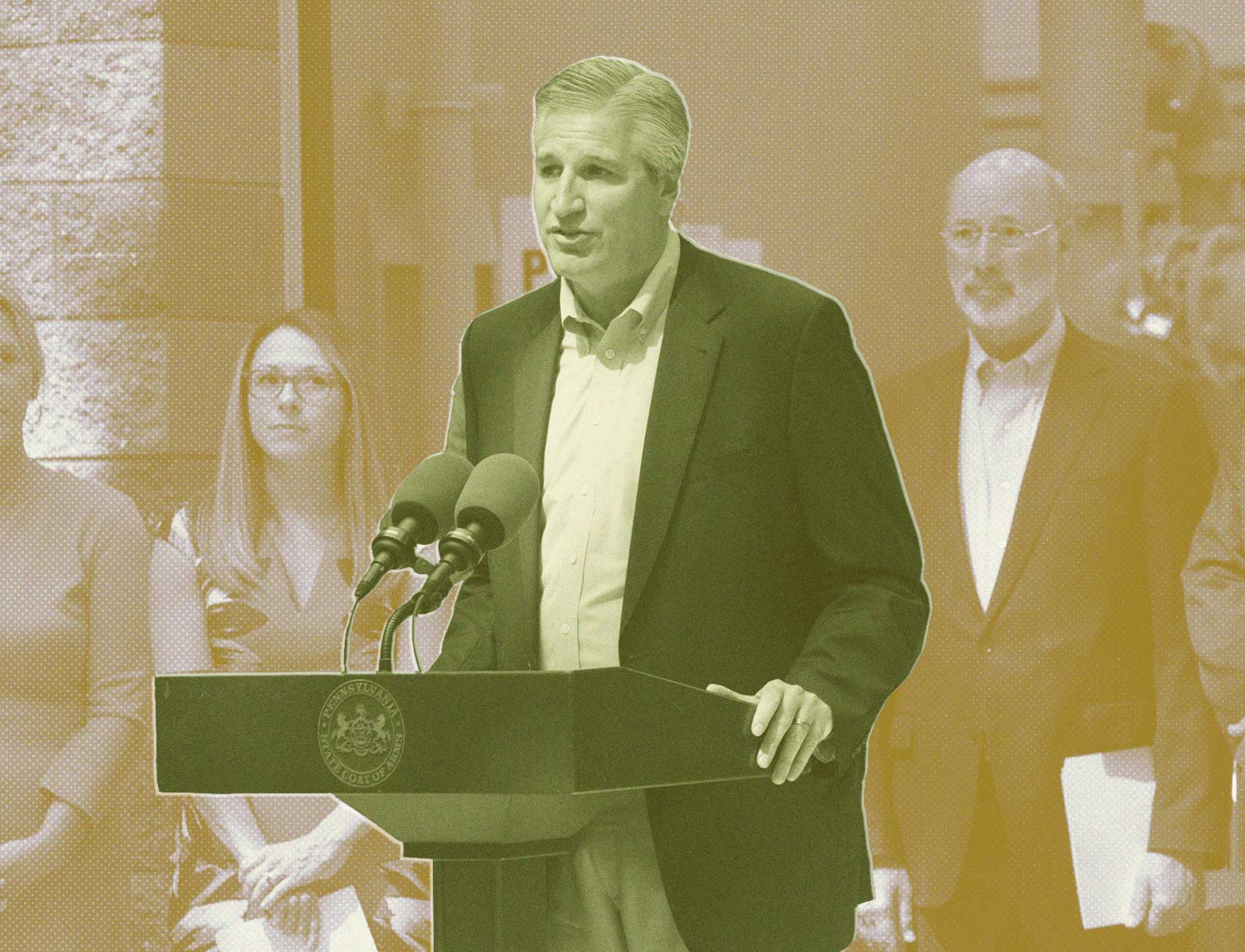

State Representative Todd Stephens, a Republican from Montgomery County, introduced the bill as part of a package intended to reduce gun violence. He has said the bill is meant to punish “violent criminals who are shooting children.” In a memo on the package, Stephens wrote, “As terror and tragedy from gun violence continue to plague our streets, never has it been more clear that we need to address sentences for violent offenders.”

Stephens did not respond to The Appeal’s request for comment.

The rate of violent crime in Pennsylvania has fallen more than 15 percent between 2010 and 2018, according to the FBI Uniform Crime Report. But more than 4,000 people have died as a result of firearm homicides since 2010, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But HB 1851 will not be effective at reducing violence, according to Natalie Kroovand Hipple, an associate professor of criminal justice at Indiana University.

Hipple told The Appeal that any intervention aimed at reducing gun violence needs to focus on people who are actually likely to use guns. With mandatory minimums, “you throw a really wide net and you catch a lot of folks you aren’t intending to catch in that net,” Hipple said.

People charged with possession of a firearm by a prohibited person are rarely accused of using the gun, according to a review by The Appeal of more than 450,000 criminal charging dockets filed in Pennsylvania between 2016 and 2017. Only about 30 percent of people who were charged with one of the crimes included in Stephens’s bill were also charged with assault. In nearly 5,000 cases, the person charged was only accused of possessing a gun when they were not supposed to, and was not charged with an assault. However, these people still would be subject to the same five-year mandatory minimum as people who actually used the gun.

Mandatory minimums for illegal possession of firearms are generally overbroad and ineffective at reducing violence in large part because they do not address the underlying reason many people carry firearms, Hipple said.

In a 2018 study by the Urban Institute, researchers interviewed nearly 100 men in Chicago who self-reported carrying a firearm illegally. More than 90 percent of the men said they carried a gun for self-protection or protection of their family. Only 6 percent said they carried a gun to commit a crime.

“We know that these folks who are involved with gun violence are inundated with trauma. They are traumatized folks—some of them from the day they are born,” Hipple said. “We’re not doing anything to deal with that. … You’re not changing behaviors by just making a mandatory minimum.”

Black men across the state would be disproportionately affected if Stephens’s bill went into effect, according to The Appeal’s review of court records.

Despite being no more than 4 percent of the state’s population, Black men accounted for nearly two-thirds of people charged with possession of a firearm by a prohibited person, including more than 3,100 who were not accused of using the firearm.

Had Stephens’s bill been in effect in 2016 and 2017, nearly 1,300 Black men in Philadelphia alone would have faced a mandatory five years in prison for illegally possessing a firearm while not being accused of using the weapon, according to The Appeal’s analysis.

“We just keep locking up the people who don’t have privilege, the people who are disadvantaged, because that’s just the way the system works,” Hipple said.

In December, Stephens submitted the language of HB 1851 and other mandatory minimum bills as amendments to a larger criminal justice reform bill, but withdrew them because of opposition.

Mandatory minimums “have not worked [and] caused many of the flaws with our current system,” J.J. Abbott, a spokesperson for Governor Tom Wolf, said in December. Abbott said Wolf intends to veto Stephens’s bill if it clears the legislature.

“If public safety is truly a legislative priority,” said Trusty of FAMM, “lawmakers should focus on directing resources into programs and practices that actually reduce violence in Pennsylvania’s communities, not wasteful and antiquated one-size-fits-all sentencing policies.”