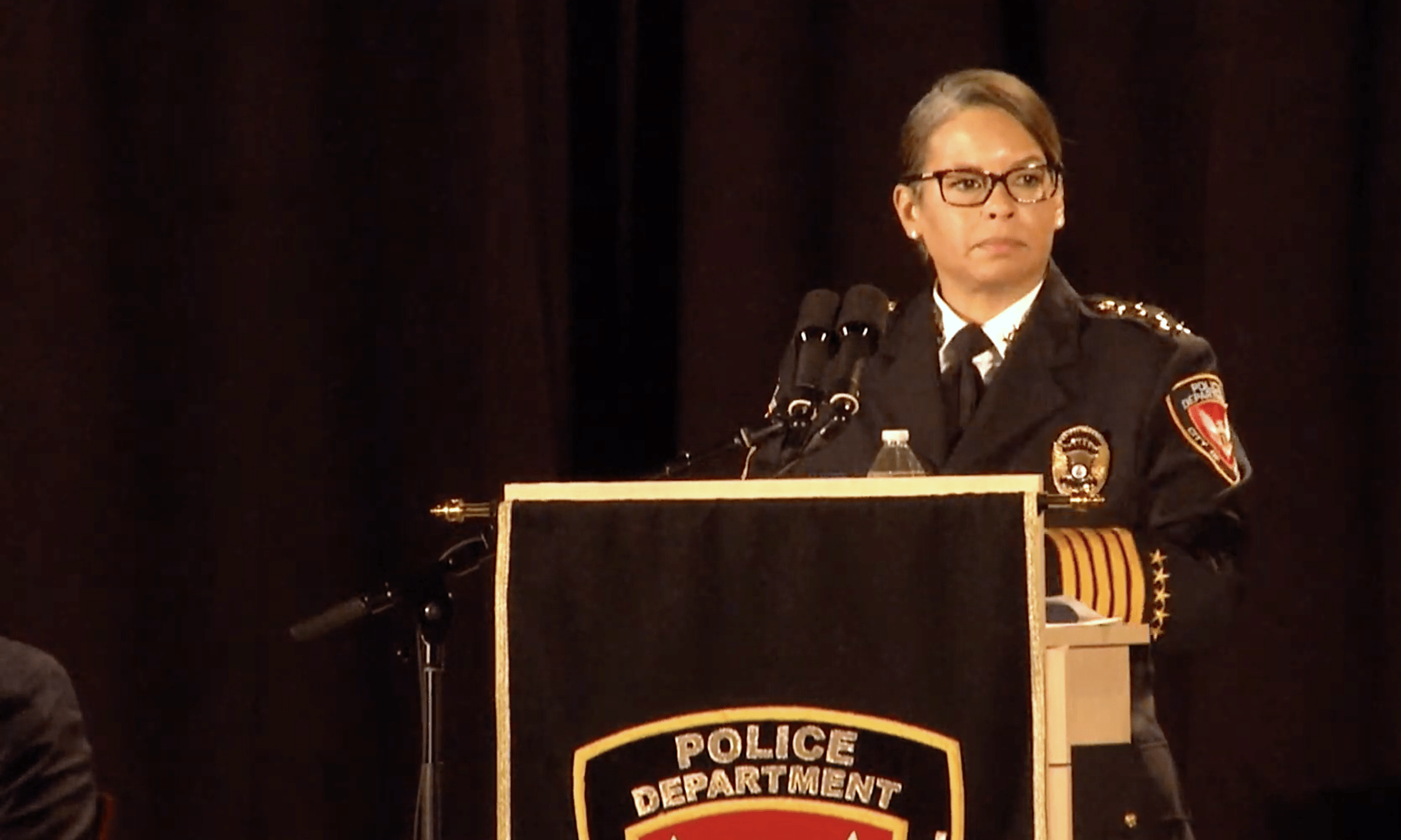

Can Residents Trust Durham’s Police Chief After She Cooperated With ICE?

Patrice Andrews once promised she’d never work with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. But in 2018, she directly ordered the arrest of immigration activists during an ICE deportation.

On Friday, Nov. 23, 2018—the day after Thanksgiving—officers with the police department of Morrisiville, North Carolina, were ordered by Police Chief Patrice Andrews to arrest local residents protesting outside the town’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) office. Those arrested were there to support Samuel Oliver-Bruno, a beloved Durham community member and a leader in the state’s sanctuary movement who had been detained inside the building. Oliver-Bruno had been avoiding deportation in “sanctuary” at CityWell United Methodist Church, in Durham, and he had left the church that day to attend what was supposed to be a procedural biometrics appointment. He was desperate to leave sanctuary and USCIS had told him that his petition for deferred action and relief from deportation couldn’t move forward unless he attended the appointment in person. But things didn’t go as planned.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents in plainclothes were waiting for Oliver-Bruno in the USCIS building. They tackled him to the ground, setting off a chain of events that would lead to multiple arrests and to Oliver-Bruno’s deportation and eventual death. It was one of the most public and traumatic immigration enforcement operations the state had ever seen.

ICE agents forced Oliver-Bruno into a van behind the USCIS office, but supporters rushed to block the vehicle from leaving. A multi-hour standoff ensued between Oliver-Bruno’s supporters, ICE, and the Morrisville Police Department, eventually ending in the arrest of 27 people, including CityWell’s pastor, Cleve May, and Oliver-Bruno’s son, Daniel Oliver-Perez. Oliver-Perez, who was 19 at the time, was charged with assaulting, resisting, or impeding ICE agents because he clung to his father as agents tried to shove him into the van, leading to a scuffle. Oliver-Perez is still dealing with the fallout from his charges.

Andrews became Morrisville’s chief of police in 2016, two years before the raid occurred. In 2017, she assured Morrisville residents that her agency would not seek out undocumented immigrants for deportation. She also said that if ICE executed raids in the region, her department would not cooperate with the agency. This occurred during Donald Trump’s tenure as one of the most anti-immigrant presidents in modern American history—compared to many other pro-Trump sheriffs and chiefs around the country, Andrews appeared to embody progressive-minded law enforcement leadership.

But Andrews did, in fact, work with ICE the day Oliver-Bruno was detained, and the residents she arrested have not forgotten that she helped carry out those arrests side by side with the federal immigration agency. In October 2021, Oliver-Bruno’s supporters were dismayed to hear that Wanda Page, Durham’s city manager, had named Andrews as Durham’s new police chief. The announcement led to glowing coverage of Andrews’ 25-year career in law enforcement—none of which mentionedOliver-Bruno. For members of North Carolina’s sizable immigrant community, the announcement reopened old wounds.

The Sanctuary Movement first formed in the United States in the 1980s to offer protection to asylum seekers fleeing Central American wars. Some communities sheltered those targeted for deportation inside churches. The movement largely fizzled out, however—until Donald Trump took office, in 2017.

Under the Trump administration, North Carolina saw a barrage of immigration enforcement actions, some in direct response to sheriffs’ decisions not to honor ICE’s detainer requests. In one raid, federal immigration authorities posed as day laborers to detain undocumented immigrants.

Less public were ICE’s silent raids, in which the agency targeted undocumented immigrants for deportation as part of regularly scheduled check-ins. Under the Trump administration, immigrants across the country arrived for their check-ins only to be detained or given 30 days to leave the country.

These silent raids were largely responsible for sparking the formation of North Carolina’s sanctuary movement. In May 2017, Juana Luz Tobar Ortega, a 45-year-old grandmother, became the first person in North Carolina to enter sanctuary because of ICE’s Trump-era policies. By August 2018, North Carolina had six immigrants in sanctuary, more than any other state in the country. One of these immigrants was Samuel Oliver-Bruno.

Oliver-Bruno entered sanctuary at CityWell United Methodist Church in December 2017, leaving behind his home in Greenville, North Carolina, his son, and wife, Julia Perez Pacheco, who relied on him for care. Immigrants in sanctuary are essentially detained in a church for months, or sometimes years, and they have to rely on members of the congregation for basic necessities such as food.

Entering sanctuary also comes with considerable risk. The only thing protecting immigrants in sanctuary from a raid is a 2011 policy memo that states ICE’s enforcement actions at sensitive locations, including “places of worship,” “should generally be avoided.” (Sanctuary also doesn’t end harassment from ICE, as evidenced by the agency’s threats to fine immigrants hundreds of thousands of dollars for their purported failure to “willfully” depart the United States.)

Oliver-Bruno was part of Colectivo Santuario, a national organization of immigrants in sanctuary who used video meetings and phone calls to organize and strategize for their freedom. Tobar Ortega, who was also part of Colectivo Santuario, knew Oliver-Bruno well. She told The Appeal that they often talked on the phone about their struggles. She said what she loved the most about Oliver-Bruno was his commitment to positivity.

“Despite the fact that he was in sanctuary and being in there was like being in jail, he still tried to be happy,” Tobar Ortega said. “Even in our hearts when we were sad, he tried to joke around and be happy. I have many memories of him hugging his wife and son. I always saw him smiling.”

Talking about Oliver-Bruno is hard for Tobar Ortega, mostly because she misses her compañero and the memories of what happened to him are painful. But she also knows the same thing could have happened to her.

“I thought, If he wins, then we’ll also win, [because] I was practically in the same [legal] situation as Samuel,” Tobar Ortega said. “The government knew of our despair. We were tired of being locked up, and the despair we felt pushed us to take risks. But we didn’t know it was a trap.”

Oliver-Bruno did not know that ICE had been monitoring both him and groups supporting North Carolina’s sanctuary movement. Once Oliver-Bruno was apprehended, ICE quickly snaked him through detention centers across the South before deporting him to Mexico just days after his arrest.

When Tobar Ortega learned of what happened, she “fell apart,” she said.

“I was in a very bad state,” Tobar Ortega said, growing emotional. “I was in a nervous shock. The pastor had to come help me that day, because I could not control myself. I felt so much fear, and I had so much hurt and pain for Samuel’s family.”

Sandra Marquina, whose husband, a pastor named Jose Chicas, was in sanctuary in Durham and was a Colectivo Santuario member, knew Oliver-Bruno’s wife, Julia Perez Pacheco.

“I remember she begged [officials] to be lenient with Samuel because his family needed him,” Marquina said. Perez Pacheco has pulmonary arterial hypertension, an aggressive and progressive condition caused by lupus, a diagnosis she received at 15. Oliver-Bruno was her caretaker. “They loved each other so much and we all cried when she spoke, because we knew she wasn’t doing well, health-wise, and it took a lot of strength for her to [speak out].”

Oliver-Bruno’s son declined to comment for this story, citing his ongoing legal issues. Back in September 2019, Oliver-Perez told me that waking up every day was a struggle because of grief, depression, stress, and fear for his future. After his dad’s deportation, he had to work full time to support his mom, derailing his plan to go to college. But his new criminal record made finding work difficult. He stopped going out with friends and stopped playing soccer, a beloved pastime he had shared with his dad.

“We feel alone right now without my dad, and because my mom’s family separated from us because of everything that happened, they’re scared ICE will come after all of us,” Oliver-Perez said in 2019. “My mom has a heart condition and can’t work at all, so my whole life is either being home with my mom or going to work so I can pay the bills.”

Oliver-Perez said there were days when he forgot that ICE took his father.

“Sometimes I’ll be getting off of work at night and I’ll feel excited that I get to go home and see him, but then I remember he’s not there,” he said.

In her role as Morrisville’s police chief, Andrews was not only present the day of Oliver-Bruno’s arrest but oversaw and directed the arrests of his supporters. She even arrested some of them herself. In audio from the March 6, 2020, courtroom trial of the arrested supporters, Andrews described a peaceful scene, one in which people were linked arm in arm and hand in hand, singing and praying together, around the ICE van that held Oliver-Bruno.

Andrews said during the trial that she worked hard to de-escalate the situation and had no desire to make arrests that day. At one point, she said, she recited the Lord’s Prayer with Oliver-Bruno’s supporters. But later, she said, walking through the crowd, she heard someone say, “Fuck the police.” This reminded her of her “post-Ferguson” policing days as an officer in Durham, she said in court testimony. On the stand, she said the person who made the comment wasn’t one of the people blocking the van and wasn’t among those arrested that day, but this is when Andrews decided to give two orders of dispersal, clearing the way for her department to begin making arrests.

Andrews declined to be interviewed for this piece, but, in a statement to The Appeal, Durham City Manager Wanda Page said it is important to note that Andrews was performing her “sworn duties” the day of Oliver-Bruno’s detainment and that her decisions “in no way implied her personal or professional support of the actions taken that day by ICE agents.”

“In fact, Chief Andrews shared with me that she repeatedly reached out to protest leaders on that day to, as she has repeatedly stated, ensure the safety of Mr. Oliver-Bruno’s supporters, the officers involved, and the general public in the immediate area, and to attempt to negotiate a peaceful resolution without making any arrests,” Page said.

One of the people arrested that day was Manju Rajendran, a longtime Durham community organizer and the interim executive director of Durham Beyond Policing. She said there were at least 200 people at the protest. She handed her toddler to her mother to join a large circle of people assembled around the ICE van.

Rajendran says that Andrews personally arrested her that day, and that the entire ordeal dealt a “serious blow” to the community’s sense of safety.

“I was really stunned to learn later that she had made a pledge a year earlier that she would not cooperate with ICE,” Rajendran said. “When presented with a choice in real life, she didn’t keep that commitment to the people of Morrisville.”.

When Page announced last year that Andrews was going to be the Durham police chief, those who’d been arrested created a petition to raise awareness about the role Andrews had played the day Oliver-Bruno was detained.

“How will she protect our community’s vulnerable undocumented immigrants?” the petition reads. “The actions she took on November 23, 2018 speak louder than any words she may share.”

Dave Jinorio Swanson and his wife, Kim, regularly visited Oliver-Bruno in sanctuary and grew close to his wife and son after he was deported. The day Oliver-Bruno was detained by ICE, Jinorio Swanson was arrested at the protest, and Kim, who was pregnant at the time, was pushed by ICE agents as they shoved Oliver-Bruno into the van.

“The reason for the petition is because what [Andrews] did was horrible, and I think she made some terrible decisions that day,” Jinorio Swanson said. “If it was that alone, I would leave things alone, if she apologized and vowed to never do something like this again, but the testimony she gave that outlined her reasoning for her actions made me incredibly nervous for the city of Durham and for our undocumented community members. She had so many options that day.”

Page said she doesn’t believe it’s “productive” to “re-litigate the actions taken by everyone involved that day,” but she said she does believe Andrews acted responsibly in her duties as chief “to protect the safety of everyone involved.”

“Freedom to peacefully protest is a sacred right that separates the United States from other countries, and both Chief Andrews and I strongly support this right,” Page said in a statement. “In this case, as she performed her duties, Chief Andrews was duty-bound to maintain order as U.S. agents carried out a warrant issued by a federal judge to arrest someone, who was, sadly, Mr. Samuel Oliver-Bruno.”

Tobar Ortega said Oliver-Bruno had “a very tough life” post-deportation and struggled with finding work while separated from his family. Then, in April 2020, he was in a horrific car accident that left him bed-ridden. In July 2021, he succumbed to his injuries and died in a hospital in Mexico, far away from his wife and son. There was one funeral in Mexico and one in Greenville, North Carolina, the community he called home for years before his life was upended by ICE. At the Greenville funeral, a laptop was set up at the front of the stage, allowing mourners to say their final goodbyes across space, time, and borders.

Page said that she and Chief Andrews understand the concerns presented in the petition, and that they feel “deep compassion” for Oliver-Bruno’s family and “those who were affected by the trauma of that day.”

“You can be assured that as the new chief of Durham’s Police Department, Chief Andrews is guided by Durham’s values that focus on equity and inclusion for everyone, despite their race, socioeconomic, or immigration status. That commitment includes her staff, who already receive ongoing training in de-escalation and racial equity,” Page said.

Back with her family in Asheboro, Tobar Ortega lives more than an hour away from Durham. She’s still adjusting to life outside sanctuary and recently described having symptoms akin to post-traumatic stress disorder. She said that after getting out of sanctuary she was initially afraid to leave her home, and she still struggles with the gnawing fear that law enforcement officials or ICE will arrive at any moment to separate her from her family.

“Me, Samuel’s family, all of us have been living through a nightmare,” Tobar Ortega said. “There is just no trust in the system, or in people who say they support us immigrants and then do not help us when they have the power to. We cannot have any trust in people like that.”