A California County’s Sheriff’s Deputies Are Accused Of Mishandling Evidence On a Staggering Scale

Deputies in Orange County wrote false reports about their collection and booking of evidence, according to internal audits kept secret for months.

Two audits conducted by the Orange County sheriff’s department uncovered a pattern of filing false reports that could call into question thousands of convictions.

Deputies booked evidence days, and sometimes weeks, after it was purportedly collected, according to an internal audit, which examined thousands of police reports filed between 2016 and 2018. Thirty percent of evidence was “booked out of policy,” according to a slide presentation describing the first audit’s findings. A second audit found that deputies had claimed to have collected evidence that was never booked.

Between 2017, before the first audit began, and October 2018, the sheriff’s department referred 15 deputies to the district attorney’s office for criminal investigation as a result of filing false reports, according to the DA’s response to Voice of OC reporter Nick Gerda’s public information request. But by the end of January 2019, the DA’s office had decided not to prosecute any of the deputies, according to a motion filed last month by Scott Sanders, an assistant public defender. Two additional deputies were later submitted and also rejected for prosecution, several months later.

It would be another 10 months before the audits became public.

Now critics are questioning why it took so long for the allegations of misconduct to come to light, and why few have been held accountable. Two of the deputies were promoted after criminal charges were rejected, according to a motion that Sanders filed this month.

By keeping the findings of the audit secret, Sanders said, the department potentially violated the rights of thousands of people who were accused of crimes.

The sheriff’s department did not respond to requests for comment from The Appeal.

Booking evidence late or not at all compromises the integrity of an unknown number of prosecutions, according to Somil Trivedi, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU.

“When there is a possibility that evidence has been contaminated, defendants rightly get to exclude that evidence because we don’t want to even take the risk that someone could have intentionally or unintentionally messed with it because cases can often hinge on it,” said Trivedi. “That is why this is so disturbing.”

The scandal’s impact is not just limited to those whose evidence was mishandled or never booked, said Sanders. Prosecutors have a constitutional obligation to turn over to the defense any evidence that could be exculpatory, such as evidence of a witness’s dishonesty. This includes, Sanders said, a deputy who has a history of filing false reports.

“Officer takes the stand, he testifies how he handled evidence in a particular case,” said Sanders. “We’ve been robbed of the opportunity for years now to question those deputies about the fact that in reality they have repeatedly made false reports, whether they collected evidence, whether they booked evidence. For the fact-finder, for the juror, when they’re relying upon these witnesses, they’re probably relying upon them with an incomplete set of facts bearing on their credibility.”

In one investigation, the department found that Sheriff’s Deputy Bryce Simpson falsely claimed he booked evidence in 74 cases, according to a motion Sanders filed last month. In 56 of those cases, no evidence was booked at all, and in 18 only some of the evidence he reported was booked. Still, the DA’s office declined to prosecute Simpson.

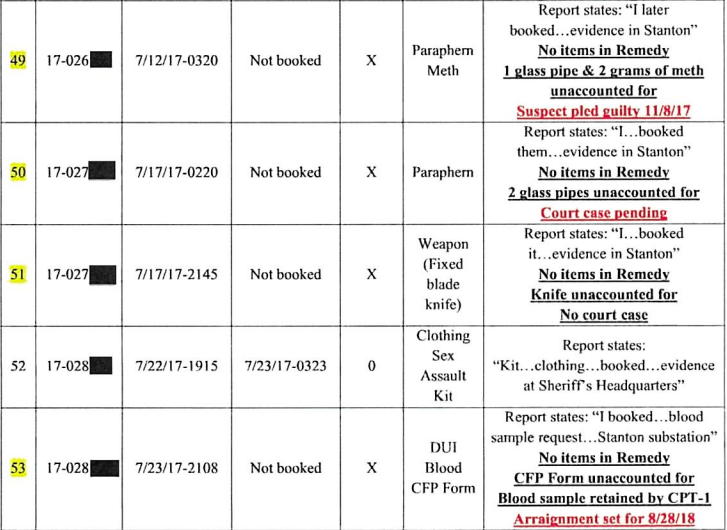

In Sanders’s most recent motion, filed on Feb. 18, he attached formerly confidential sheriff’s department internal criminal investigative memos for three deputies, including Joseph Atkinson. Atkinson repeatedly claimed to have booked evidence when the evidence was never booked, according to the report completed in May 2018.

Evidence detailed in 26 of Atkinson’s reports could not be located, including a knife, photos, a note allegedly written by a missing person, and drug paraphernalia.

In seven of the deputy’s cases, methamphetamine or methamphetamine paraphernalia had not been booked, contrary to his reports. Out of those, the resolutions of the cases vary: Two cases were dismissed, at the prosecutor’s request; one was dismissed after drug treatment was completed; and two people pleaded guilty and were sentenced to 30 days in jail. In another case, the accused did not appear in court and a bench warrant was issued. No resolution is detailed for the remaining case.

An investigation into another deputy found that she booked evidence—a boxcutter and glass smoking pipe—37 days after the guilty plea, according to the internal memo. She falsely claimed in her report that she had booked the evidence on the day of the arrest.

“It’s officers making false report after false report,” said Sanders. “Those are huge problems and would have seemingly supported prosecution.”

Sheriff’s investigators launched the first audit on Jan. 24, 2018. They reviewed 27,091 reports where items were booked. According to their findings, 30 percent of evidence was “booked outside of policy.” More than 25 percent of the deputies had taken over 30 days to book some items of evidence. Their results were shared with the sheriff and undersheriff on June 28, 2018.

A second audit also found misconduct. According to the audit report, which is dated February 2019 and authored by the department’s constitutional policing advisor, a randomized sample of 450 reports were reviewed. In 57 of those cases, deputies did not book evidence that they claimed they had collected. The sheriff’s department did not share these findings with the public, defense counsel, or the prosecutor’s office. In fact, the audits did not become public until November.. On Nov. 18, the Orange County Register broke the story about the first audit, and then reported on the second audit a week later.

Spitzer, the district attorney, has said he only learned of the audit in November, after he was contacted by a reporter.

“As soon as he [Spitzer] was made aware of this systemic issue, he immediately told the Sheriff’s Department what information the District Attorney’s Office needed in order to fulfill its legal obligation to provide this information to defendants and defense counsel,” wrote DA’s office spokesperson Kimberly Edds in a text message to The Appeal.

In a letter to Sheriff Don Barnes dated Nov. 21, 2019, Spitzer wrote that the sheriff’s office first briefed him on the audits on Nov. 18.

“I have concerns that my office may have filed and prosecuted criminal charges against individuals based on OCSD reports that inaccurately stated evidence had been booked,” Spitzer wrote. “My goal is to identify any and all cases handled by OCDA where a defendant’s due process rights may have been negatively impacted by having evidence collected but not booked.”

Earlier this month, the sheriff’s department announced it was reviewing, in collaboration with the DA’s office, more than 22,000 cases, from March 22, 2015 to March 22, 2018. When asked the status of the review, the DA’s office wrote in a text message to The Appeal that it is prevented from commenting further because of the reopened criminal investigation into the 17 deputies, but that defense counsel has and will continue to be notified.

In late January, according to Voice of OC, the DA’s office had identified 91 criminal cases in which a person was convicted of a crime in which “evidence was either never booked or booked after a defendant was convicted.” At that time, only 2 percent of the review was complete.

“In every one of these cases, a person accused of a crime is owed their right to due process in the criminal justice system,” Barnes said in a statement released this month. “In some cases, there is also a victim who wants to see justice served. I am not only mindful of those facts, they’re the driving force behind my desire to uncover the full scope of this issue and hold accountable those who violated policy.”

But Barnes didn’t take that position during the months when the audits were kept secret. In a statement released on the day the first Register story was published, the sheriff defended his department. “The audit achieved its intended goal and has made our agency better,” he said. In December, he told City News Service that only one case had been “impacted.” He also denied his department had a duty to share the audits with the DA’s office, according to an NPR report published that month.

Sanders, the assistant public defender, condemned the department’s handling of the audits.

“They knew the problem was catastrophic to the criminal justice system and they stopped and they didn’t make disclosures,” said Sanders. “It’s a criminal cover-up.”

Both the sheriff’s department and the DA’s office have been plagued by scandals in recent years. Spitzer came into office on Jan. 7, 2019 after campaigning as a reformer against his predecessor, Tony Rackauckas.

“Rackauckas has been in office for 20 years. This breeds corruption, complacency and a public failure of leadership,” Spitzer’s campaign website reads. “I will uphold justice, fight for our civil liberties and act as a model of ethical conduct with honesty, integrity and complete transparency.”

In 2014, Sanders discovered a decades-long secret jailhouse informant program during his representation of Scott Dekraai, who was charged with murdering eight people. Dekraai pleaded guilty to eight counts of murder and was sentenced to life without parole. As a result of prosecutorial misconduct, Superior Court Judge Thomas Goethals recused the entire district attorney’s office from prosecuting Dekraai’s sentencing phase. His decision was upheld on appeal.

The prosecutors’ actions had irreparably harmed Dekraai’s right to a fair sentencing trial and, therefore, Goethals ruled, he could not consider a death sentence. They had, he wrote in a court order, engaged in “chronic obstructionism … with respect to discovery compliance.”

“Ongoing prosecutorial misconduct related to discovery proceedings,” he wrote, “effectively compromised this defendant’s right to procedural and substantive due process and prospectively to a fair penalty trial.”

And in a separate, still unraveling scandal, a defense attorney discovered in 2018 that sheriff’s deputies had listened to and recorded confidential calls between pretrial detainees and their attorneys. Listening to or recording an incarcerated person’s calls with their attorney is a felony in California. Last year, attorneys with the public defenders office, including Sanders, asked the Orange County Superior Court to help determine how many calls were recorded, whose calls were listened to by law enforcement, and what calls were turned over to the district attorney’s office.

Despite Spitzer’s public pronouncements that this latest scandal will be investigated, Sanders fears that, once again, law enforcement will get away with violating the rights of those accused of crimes in Orange County.

“It’s just this concern when it’s the same two agencies that have problematic responses and explanations,” said Sanders. “You hope it’s being done right for the sake of our clients. They’re well overdue.”