Orange County’s ‘Standard Operating Procedure’

The California county has a thin blue line that appears to protect not just the police, but also the DA’s office, criminal justice advocates say.

Handcuffed and lying on the ground, Mohamed Sayem asked Orange County officers Michael Devitt and Eric Ota if they were going to shoot him.

“No,” Devitt said.

“Like to,” Ota replied.

Moments earlier, at about 6 a.m. on Aug. 19, 2018, Devitt had dragged Sayem from his jeep, and punched him several times in the face and stomach. The incident was captured on Devitt’s dashboard camera.

The officers had woken Sayem, who appeared intoxicated and had fallen asleep. They asked him for identification. After trading insults, Sayem placed his foot outside the jeep twice, and that’s when Devitt grabbed him and punched him.

After the altercation, Sgt. Christopher Hibbs, assigned to investigate Devitt’s use of force, arrived on the scene. Devitt reported to Hibbs that Sayem “‘went into this ‘verbal berate’” using a racial slur. He said that Sayem “comes up on me” and “tried to bear hug me.” He then told Hibbs that Sayem had stepped outside the car, and was “basically standing over me.” He had begun painting the picture that he was acting in self defense.

There is no depiction of a bear hug on the video or of Sayem using racist language. Nor does the dashcam video show Sayem stepping out of the car; in it Sayem is holding on to the steering wheel when Devitt dragged him out of the car.

Sayem was taken to the county jail and charged with felony resisting and deterring an executive officer and public intoxication, which together carry a jail sentence of up to three years and six months.

On June 4, Scott Sanders, Sayem’s public defender, filed a motion to compel the Orange County district attorney’s office to provide critical pieces of as yet undisclosed evidence, and to allow him to take testimony from the officers. Sanders believes that this additional information could cast further doubt on the credibility of the officers’ accounts, and help get the charges against Sayem dropped. A ruling on his motion is pending.

The criminal justice system in Orange County is in crisis.

Brendan Hamme staff attorney at the ACLU of Southern California

The Orange County sheriff’s department confirmed that Ota and Devitt are on active duty with the department and referred The Appeal to a videotaped statement that was released in October. “The suspect did not comply with the deputy’s directives. An appropriate use of force was utilized at that time,” Sandra Hutchens, who was then the sheriff, said in the video. “My deputy is not on trial. The suspect is on trial for assaulting a peace officer.”

Sayem’s ongoing legal battle is up against a police department that, according to advocates, works hand-in-hand with the district attorney’s office to routinely violate the rights of community members with almost complete impunity. And despite the recent election of District Attorney Todd Spitzer, who has promised reforms, advocates say that abuse and corruption persist.

“What happened to Sayem absolutely reflects the larger systemic issues with the sheriff’s department and the district attorney’s office,” said Brendan Hamme, staff attorney at the ACLU of Southern California. “The criminal justice system in Orange County is in crisis.”

‘A field of facts’

Sanders said the first offense against Sayem was the assault, and the second was the cover-up—a pattern out of the Orange County playbook. In addition to Devitt’s reports, which contradicted video and audio recordings, further evidence of the incident has been suppressed, according to Sanders’s motion.

Deputy Brant Lewis and Deputy Blake Blaney arrived at the scene shortly after Hibbs, Devitt’s dashcam video shows. Lewis appeared to turn off Hibbs’s audio recording device at 6:28 a.m. while the video continues to roll for 11 more minutes. At 6:39, Devitt entered a written account of the incident, which differed significantly from his initial oral statement and the available dashcam videos, according to Sanders’s motion.

It is not known what the officers discussed during that period. Sanders thinks that additional dashcam recordings will provide crucial audio evidence and is requesting that the sheriff’s department turn it over.

In his written statement, filed at the scene, Devitt said Sayem had “raised his arms towards my face,” and stepped out of the vehicle, according to Sanders’s motion. Sayem then, Devitt claimed, “started grabbing at my vest.” Devitt said he then punched Sayem four times. Hibbs approved this account, according to Sanders’s motion.

In Hutchens’s video response, she said Devitt’s statement is consistent with what is depicted in the video. “I work in a field of facts,” she said. “I stand 100 percent behind my deputy. What he wrote in his report is exactly what occurred in the video and what I personally saw in the video.”

Sanders has asked the court to compel the district attorney’s office to turn over dashcam videos from Ota’s, Lewis’s, and Blaney’s cars. The sheriff’s office says such evidence does not exist.

But Hibbs wrote in a use of force report that he had collected Ota’s video. In a subsequent statement, Hibbs said Ota had not turned on his camera, according to Sanders’s motion. Ota wrote in his own statement that he had failed to turn on his dashcam video and, as a result, Hibbs reprimanded him. The DA’s office originally said the internal use of force report did not exist, according to Sanders’s motion.

Lewis and Blaney said they did not turn on their cameras either when they arrived at the scene. Their declarations include identical paragraphs, including a typo, stating that they did not turn on their dashcam video because they were not required to as they arrived out of “personal concern for Devitt,” not in response to a service call.

“It’s bad enough they lied and made up the story. But why is [Mr. Sayem] facing a felony right now?” Sanders told The Appeal. “It’s just obvious—cop got out of control, blew it, didn’t want to tell the truth so he decided to put the blame on Mr. Sayem.”

Culture of impunity

Sayem’s case illustrates the “culture of impunity” that exists for Orange County’s district attorney and sheriff, according to Laura Fernandez, a lecturer at Yale Law School who specializes in prosecutorial accountability. “The complete and utter lack of accountability we’ve seen in Orange County only serves to reinforce what amounts to a toxic culture,” she wrote in an email to The Appeal.

Scott Sanders is well acquainted with that culture. In 2014, he uncovered a longstanding informant scandal involving the sheriff’s department and the DA’s office. While defending Scott Dekraai, who pleaded guilty to killing eight people in 2011, Sanders discovered that the sheriff’s department and the district attorney’s office had allegedly been operating a secret informant program for more than 30 years.

Sanders uncovered that, for more than three decades, the sheriff’s department operated an elaborate jailhouse informant program executed by members of its Special Handling unit. Informants were promised leniency in exchange for their cooperation, and some would threaten their targets with violence in an effort to get them to confess, according to the ACLU of Southern California. No charges have ever been brought against any prosecutors nor sheriff’s department officials linked to the scandal.

After the program was revealed, the trial court recused the entire Orange County DA’s office from Dekraai’s penalty phase. The decision was appealed by then California Attorney General Kamala Harris’s office, but the appeals court upheld the lower court’s ruling. The lower court judge later found the misconduct so severe that it warranted prohibiting the attorney general’s office from pursuing the death penalty.

The discovery also prompted a suit from the ACLU and the ACLU of Southern California against the DA’s office and the sheriff’s department, as well as an investigation by the state attorney general’s office.

However, in April, it was revealed that the attorney general’s investigation, which began in 2015 under Harris, had ended. The office has not released its findings, issued a report, or announced if any charges or disciplinary measures will be taken. No official announcement was made. Instead, a deputy attorney general made the revelation in court, according to OC Weekly. The attorney general’s office, now led by Xavier Becerra, did not respond to requests for comment from The Appeal.

The attorney general’s investigation further reinforced that the sheriff’s and district attorney’s offices are not held accountable, said Sanders. “These folks have never been taught that the rules are paramount,” he said. “The rule is, ‘Get the guy.’ Worry about the rest later. Ultimately, you’ll never have to worry.”

The U.S. Department of Justice launched an investigation in 2016, which remains open. And DA Spitzer announced this year that his office will also investigate. Sheriff Don Barnes sent a letter to Becerra in January informing him that the sheriff’s department would proceed with an internal investigation. Barnes wrote that his department had sent numerous inquiries to the attorney general’s office about the status of its investigation, but had not received any replies.

In Orange County, criminal prosecutions of officers are virtually nonexistent, according to advocates. One of the few deputies to be prosecuted in recent years was Hibbs, the officer who investigated Devitt’s use of force against Sayem. In 2009, Hibbs was charged with assault after he allegedly used a Taser on a person who was handcuffed. The jury could not reach a verdict and the charges were subsequently dropped.

“That thin blue line exists,” said Sanders. “They rally behind each other and then if folks with more power won’t put an end to it, it just continues.” It appears that the line of protection extends to the DA’s office.

On June 11, Voice of OC reported that in December, his last month in office, District Attorney Tony Rackauckas sent a letter to Hutchens and Sheriff-elect Barnes, informing them of his decision not to tell defense attorneys about the possible misconduct of 10 deputies who were involved in the operation of the informant program. The deputies had been accused of lying and/or concealing evidence. The letter also says that the state attorney general’s office will not be pursuing criminal charges against the sheriff’s or district attorney’s offices—a statement made several months before the public learned the investigation had ended.

Rackauckas’s letter is the latest revelation in what advocates say is an incessant stream of corruption. This month, for instance, Alisha Montoro, a public defender, alleged that Deputy Victor Valdez told a confidential informant in 2015 to inject heroin into Craig Tanber so he would be easier to arrest and more likely to confess, according to local news reports. Tanber was arrested on Sept. 11, 2015, and charged with murder. At a recent hearing, Valdez, who has been granted immunity for his testimony by the DA’s office, denied the allegations, according to the local ABC affiliate.

When officers are not held accountable for abuse and corruption, it sends a “toxic message” to community members, said Carl Takei, a senior staff attorney with the national office of the ACLU. “Having accountability mechanisms in place is important not only for departmental culture but also for public trust in the police,” said Takei. “If the culture of the police department is to sweep complaints under the rug then it sends the opposite message—that the police can violate people’s rights with impunity and there’s nothing to stop them.”

‘Just a different name on the door’

During his 2018 campaign against the incumbent Rackauckas for DA, Spitzer promised to reform the scandal-plagued office. The assurance drew support from Paul Wilson, whose wife, Christy, was one of eight people murdered by Sanders’s client, Dekraai.

After Wilson learned of the informant scandal, he joined defense attorney Sanders as an advocate to help expose police-and-prosecutor corruption and abuse in Orange County. As part of his newfound mission, Wilson lent his support to Spitzer in his bid to unseat Rackauckas, who had been in office since 1999.

“I considered this guy an ally and a friend,” Wilson told The Appeal of Spitzer. In the announcement of a campaign ad in which Wilson appears, Spitzer said, “Orange County is rapidly waking up to Rackauckas’s corruption, as the saga of lies, cheating, and injustice continues to unfold. Tony Rackauckas acts as if he is above the law but as scandal pours out of the District Attorney’s office he is no longer immune to his abuse of power.”

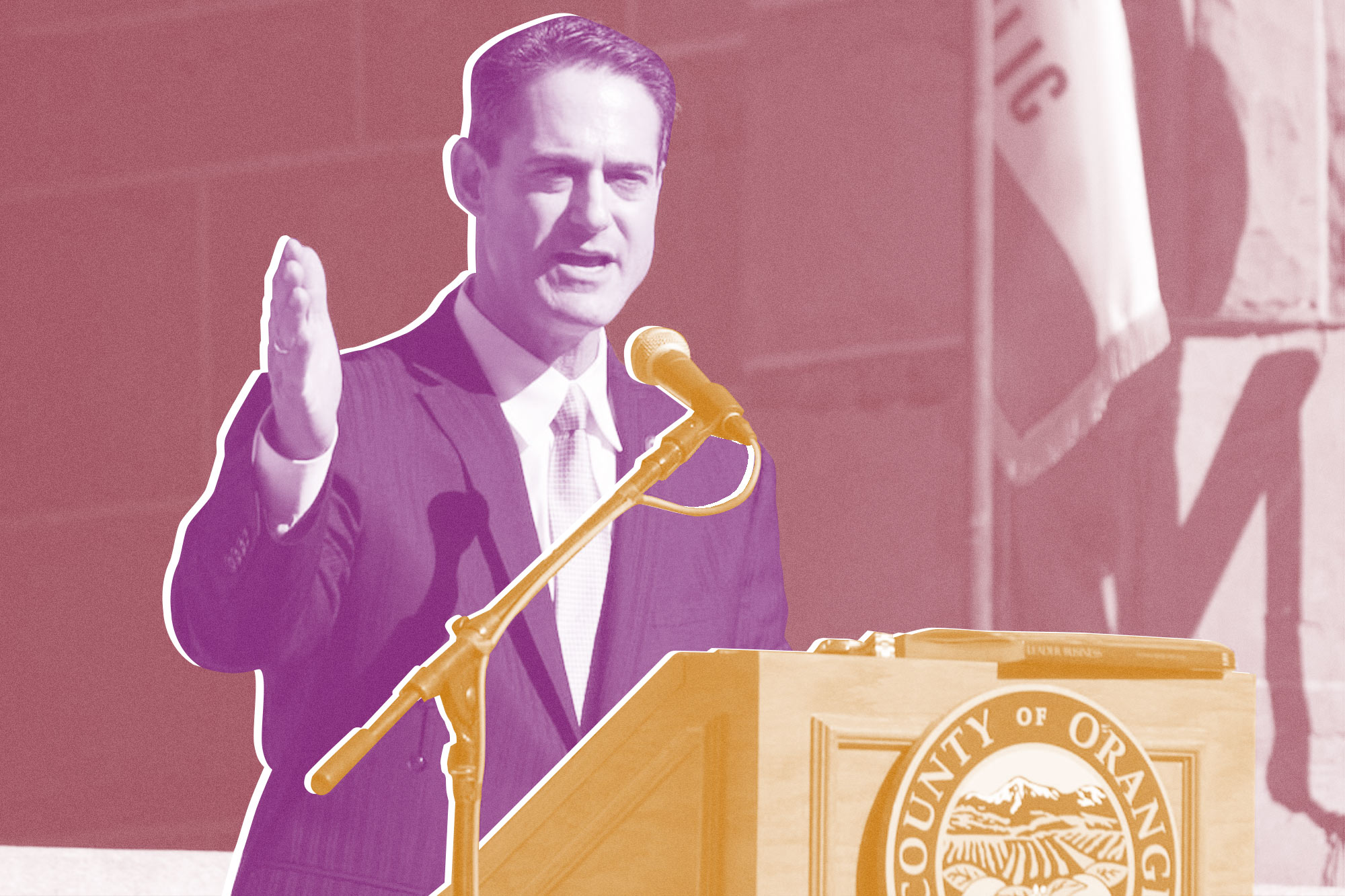

In a memo to his staff, Spitzer detailed several changes that his office planned, including the creation of a senior ethics officer and a new protocol for working with jailhouse informants.

“As the newly elected district attorney, many stakeholders in the Orange County criminal justice community expect that under my leadership the Orange County District Attorney’s Office (OCDA) will set in motion significant policy changes that address the failings of the prior administration,” Spitzer wrote. His proposed informant protocol requires prosecutors to, among other obligations, seek corroboration for informants’ statements and to find out whether the information shared was available from publicly available sources, like news reports.

But there are already signs that Spitzer’s actions may not match his campaign rhetoric, according to Wilson and other advocates. For instance, his informant protocol is nearly identical to the one implemented by his predecessor in 2017. And the use of an ethics officer is also an established practice. In 2017, Rackauckas designated an outside lawyer to hear ethics complaints from members of the district attorney’s office.

Spitzer has also kept in place the “Spit and Acquit” program in which those arrested for misdemeanors can have their charges dismissed if they agree to submit a DNA sample to a database maintained by the district attorney’s office. “District Attorney Todd Spitzer has represented that his office has made significant reforms,” said Hamme, of the ACLU of Southern California. “In reality his office seems to be operating no differently than Tony Rackauckas’s.”

After taking office, Spitzer promoted Dan Wagner, the lead prosecutor in the Dekraai case.** “To me that is the biggest slap in the face,” said Wilson. And although Sayem was charged under the previous administration, Spitzer’s office has not dismissed the case, despite the existing evidence that contradicts police statements.

Wilson has been attending Sayem’s court hearings as part of his work to expose malfeasance.

“The video’s all there,” said Wilson. “It’s just typical of what happens here with those two departments.”

Ultimately, Wilson said, Spitzer could help put a stop to the county’s “prolific” abuse of power. But he’s still waiting for the new district attorney’s campaign promises to come to fruition.

“It’s just a different name on the door,” said Wilson. “There’s no change. It’s standard operating procedure over there.”

**Update (Jun. 20, 2019): After the publication of this article, District Attorney Todd Spitzer’s office sent a statement, denying that Spitzer promoted Wagner. “Just before leaving office, Tony Rackauckas moved Mr. Wagner from an at-will position back to a civil service protected job,” reads the statement. “After District Attorney Spitzer was sworn in, he transferred Mr. Wagner from a civil service protected job back to an at-will position. District Attorney Spitzer removed Mr. Wagner from the Office’s Special Circumstances Committee.”

However, the local ABC affiliate reported what appears to be contradictory comments from Spitzer.

“So, it’s interesting, just before Mr. Rackauckas left office, he demoted Mr. Wagner from Assistant District Attorney, who was ‘at will,’ to a civil service position,” Spitzer said, according to the news report. “He did that to protect him from any future disciplinary action.”

“I put Mr. Wagner back in an ‘at will’ position until the outcome of this investigation,” Spitzer said, according to the ABC affiliate.