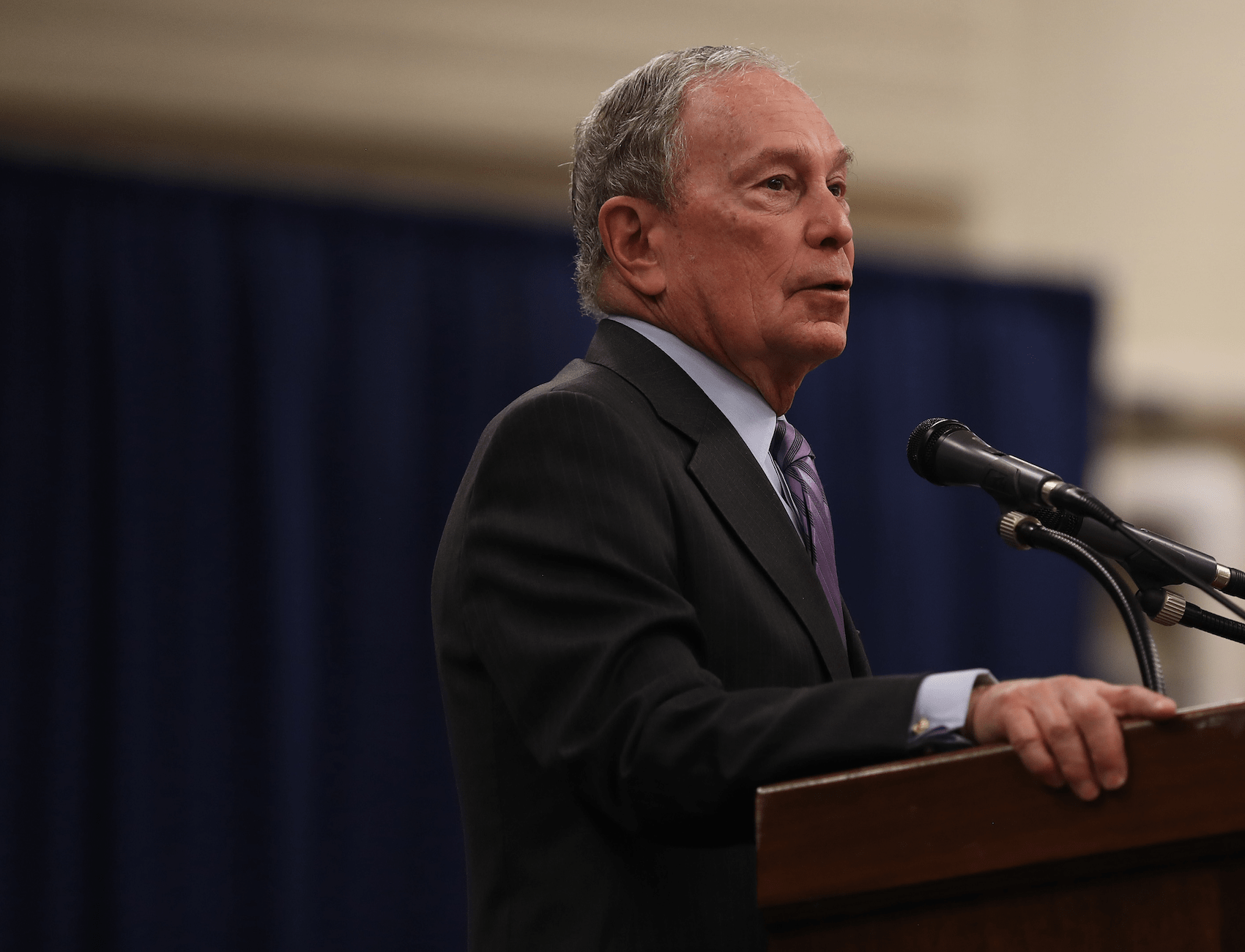

Bloomberg’s Stop-and-Frisk Philosophy Also Informs the Rest of His Work on Gun Violence Prevention

We need to be more critical of the former New York mayor’s outsize influence on the gun control movement.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis on important issues and actors in the criminal legal system.

Michael Bloomberg’s wealth and influence have fundamentally shaped today’s gun violence prevention movement—and the same misguided, law-and-order principles that guide his thinking on stop-and-frisk have also permeated the movement. I saw this in action as one of the lead organizers of the March for Our Lives in New York City, and in the gun violence prevention work I’ve done since.

Bloomberg’s principles dictated the ethos of Mayors Against Illegal Guns, a coalition of mayors that advocated for stricter gun-control laws across the country, which he founded with then-Boston Mayor Thomas Menino in 2006. Mayors Against Illegal Guns fought for many of the policies that dominate the discourse of mainstream gun violence prevention organizations today: comprehensive background checks, closing loopholes, and red flag laws. I believe many of these laws are effective and worth pursuing, and I fought to pass the red flag law in New York. But the moniker Mayors Against Illegal Guns belies what for some was its underlying purpose: the continued criminalization of Black and Latinx men.

For lawyers working in criminal justice and people like me who are going into public defense, we are aware of a grim reality: Certain bread-and-butter gun laws disproportionately affect communities of color. This is where Bloomberg’s past policies as New York City’s mayor and his relationship to gun violence prevention comes into the greatest tension.

Both mayors have been criticized by civil liberties groups for their records on race and policing. In 2015, the ACLU of Massachusetts found gross racial disparities in stop-and-frisks conducted by the Boston Police Department that could not be explained by crime or other nonracial factors. As Bloomberg continues his campaign for the presidential nomination, he has been questioned on his racist policy of stop-and-frisk and his support of broken-windows style policing during his tenure as mayor. When Bloomberg’s case for stop-and-frisk went to the courts in Floyd v. City of New York, the court found not only that the policy was done in a manner that violated the Constitution, but that nearly 9 out of 10 of those New Yorkers stopped and frisked were completely innocent. Bloomberg appealed the case and lost again.

The same dangerous personal philosophy that informed these policies also informed Bloomberg’s strategies and focus in the gun violence prevention movement. To understand how Bloomberg thinks, look no further than the audio of him from 2015 that was recently widely shared on social media. In it, Bloomberg can be heard saying, “Ninety-five percent of your murders—murderers and murder victims—fit one M.O. You can just take the description, Xerox it and pass it out to all the cops. They are male, minorities, 16 to 25 … and that’s where the real crime is.”

Bloomberg only apologized for stop-and-frisk half-heartedly late last year when he began his run for president. He has done very little in the last several years to make up for any of the havoc laid by this policy. This is because, quite simply, he is not sorry. The underlying belief that motivated stop-and-frisk was that Black and Latinx people were dangerous.

In his 2008 State of the City address, Bloomberg said Mayors Against Illegal Guns had “put the issue of illegal guns back on the national agenda … beating back federal legislation that would have made it easier to traffic in illegal guns.” As many advocates from smaller organizations have lamented, especially those operating organizations in communities seriously affected by mass incarceration and the criminalization of poverty, these bright-line issues do not take into account the many collateral consequences of gun control regimes.

For Mayors Against Illegal Guns, the messaging was simple: Don’t break the law. (If this is a familiar central organizing ideology, it is because it is one often utilized by conservative politicians to justify harsh policies and surveillance.) But certain laws and sentencing requirements are often just as destructive in these communities as the guns themselves.

Possession of a firearm by a felon, on its own, is considered a felony crime, usually punishable by a prison sentence of several years. This is for simple possession, with no other crime involved. The law-and-order approach ignores a key reality that often those punished for this kind of crime are nonwhite and poor. There is little recourse for people involved in such cases generally. To regain possession rights, individuals need some form of pardon, expungement, or a record seal. The process to do so is not straightforward, especially not for a person with few resources.

Anecdotes never tell the full story, but they can be useful indicators for understanding how policies affect people in the real world. Ask any attorney in criminal court, and they’ll tell you a horror story about mandatory sentences related to gun possession laws. I’ve met with clients on Rikers Island and know several individuals who had virtually nonexistent and nonviolent criminal histories who will spend years of their life locked in a cage because they were in possession of a firearm. These individuals consistently shared two characteristics: They were Black and poor. Quite often, they possessed weapons out of fear of danger in their community and fear of the police. The law-and-order approach to gun violence, often promulgated in various forms, is appealing because of its simple messaging and “common sense” approach. It suffers from a severe, fatal flaw: It is unmistakably white.

Bloomberg’s ethos carried on into Everytown for Gun Safety after Mayors Against Illegal Guns merged in 2013 with Moms Demand Action, a grassroots organization that formed in response to the tragic shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. Based on reporting that relied on the limited available information, at least one-third of Everytown is funded by Bloomberg. While Everytown collects and distributes gun violence research, advocates for policies, and funds candidates fighting against gun violence, Moms Demand Action forms the nonprofit’s grassroots activism arm.

As BuzzFeed reported in November, many volunteers and members of the various Everytown affiliates do not consider themselves beholden to Bloomberg, but they appreciate his work in the movement. “While he’s our largest donor, it doesn’t mean he is the organization himself,” said Alanna Miller, 19, the Students Demand Action volunteer leader at Duke University. But regardless of how individuals or even organizing chapters of various groups feel, none can discount the influence and power of Bloomberg on the Everytown organization itself and in the gun violence prevention movement.

This is not to criticize the meaningful accomplishments of these groups or those affiliated with them. The accomplishments of Everytown are too numerous to count, and by almost any measure objectively positive developments, like when it contributed nearly $16 million to support and win in passing Nevada’s background checks ballot question in 2016. But we can’t ignore Bloomberg’s impact on the strategies and priorities of many organizations and advocates. Even today on the Everytown website, you can find the “Statement of Principles” of Mayors Against Illegal Guns. Among them, supporting “intelligence-led policing.” With a person with Bloomberg’s history of surveillance and abuse at the helm, surely such language should give any social justice advocate pause.

I first came into contact with Everytown in 2018, after a gunman killed 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, and the students there called for national action, launching the largest set of youth protests since the Vietnam War. I created a Facebook group called March For Our Lives – NYC. Within 24 hours, 15,000 people had joined, and a wonderful Moms Demand Action volunteer in the city contacted me to help find a meeting place for various gun violence prevention organizations in the city to plan the march. Everytown would end up pouring at least $2.5 million into the planning and execution of the marches across the United States. For New York City alone it would spend in the ballpark of $100,000.

Everytown provided much of the initial backbone and structure to this event; you can still find the tool kits they provided to organizers online. The credit for the event itself still goes to the strong voices of the Parkland students and the work of many organizers all over the United States, and I still believe millions of people would have protested regardless of the infrastructure behind the event. However, the influence and power of Everytown should not be minimized, and that power is directly tied to Bloomberg.

In this race for president, one of Bloomberg’s greatest assets is his relationship to the gun violence prevention movement. In a sense he has a built-in machine, a full-sourced policy shop of volunteers. Although Everytown maintains its independence from Bloomberg, his campaign rented the organization’s email list for a hefty $3.2 million, and at least a half-dozen former Everytown and Moms Demand Action officials have joined his campaign.

But this isn’t particularly surprising, and for many it is not problematic. The bigger issue is that Bloomberg’s history, replete with alarming problems related to race, policing, and surveillance, is ignored in part because of his years of building up his reputation in this particular arena. For the casual political observer, Mike is the gun-control guy. And he is. But that legacy is more complicated than many would like to acknowledge.

Alex Clavering is a third-year student at Columbia Law School who works as a legal extern with the Neighborhood Defender Service of Harlem. He has done extensive work in gun violence prevention organizing and is pursuing a career in public defense.