Mayors Running for President Take Heat on Police Brutality and Racial Profiling During Debates

Current and former mayors were questioned about how they managed their police departments.

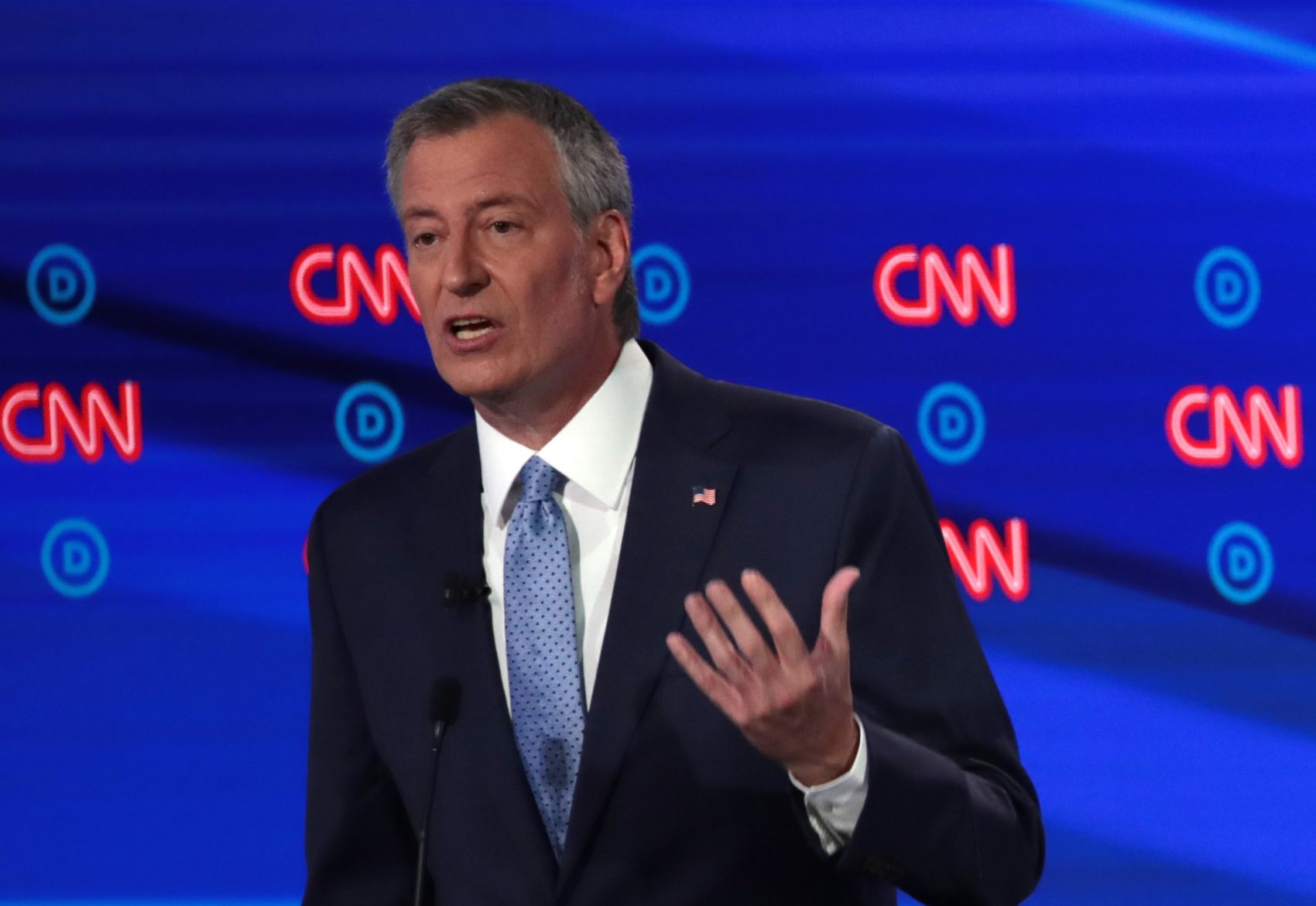

On Wednesday, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio was more than 600 miles away from home at Detroit’s ornate Fox Theater, where he’d taken the debate stage with nine other Democratic presidential candidates. But he didn’t escape hometown protesters dissatisfied with his performance on issues of police accountability.

“Fire Pantaleo, fire Pantaleo, fire Pantaleo,” a small group of protesters chanted during the nationally televised debate. Their chants referenced NYPD Officer Daniel Pantaleo who, on July 17, 2014, used a banned chokehold technique to take down Eric Garner, a 43-year-old Black man allegedly selling loose cigarettes in front of a Staten Island convenience store. Garner, who died as a result of the attempted arrest, was filmed repeatedly telling Pantaleo and other officers, “I can’t breathe.” His final words became a national rallying cry for Black Lives Matter demonstrators in New York and beyond.

Yet, in the more than five years after Garner’s death, a local grand jury cleared Pantaleo of wrongdoing, the U.S. Department of Justice declined to bring criminal civil rights charges against the officer, and, to the dismay of Garner’s family and activists, de Blasio hasn’t ordered his police chief to fire Pantaleo. At the debate, he promised Garner’s family justice “in the next 30 days,” claiming that his hands were tied until recently because of a federal investigation.

His comment had echoes of one from Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana, who fielded a question on Tuesday night from debate moderator Don Lemon over the lack of racial diversity in his city’s police force. Racial tensions in South Bend boiled over after the June 16 fatal shooting of a Black man by a police officer. Though Buttigieg said his city was revising its use of force policy and rethinking the composition of the board of safety that handles police matters, he also deflected some responsibility.

“I’ve proposed a Douglass plan [named after abolitionist Frederick Douglass] to tackle this issue nationally, because mayors have hit the limits of what you can do unless there is national action,” he said.

But experts on policing say that both mayors may have understated their own power.

“When mayors claim that they have no influence over the discretionary decision-making of a police chief, that is bogus,” Alex Vitale, a sociology professor at New York’s Brooklyn College and the author of “The End of Policing,” told The Appeal. “At the very least, they have the power to send a message to the police chief. And if the police chief is not willing to obey, as a matter of policy, they then need a new police chief overnight.”

As city executives, most mayors oversee their city’s police, and are responsible for their behavior. They often handpick the top officials for their police departments, can influence disciplinary decisions, and can appoint people to civilian oversight boards that independently investigate abuse and misconduct allegations.

So, when a mayor fails to sideline or suspend officers at the center of fatal encounters with citizens, it’s not because they don’t have the power to do so, Vitale said.

Clarence Taylor, author of “Fight the Power,” a book about the history of police brutality against African Americans in New York City, agreed. Regarding de Blasio, he said, “It’s true that he probably can’t outright fire Pantaleo. But he can suspend him indefinitely. He does have the power to do that. … He got caught yesterday and rightfully so.”

De Blasio’s and Buttigieg’s campaigns did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

New Jersey Senator Cory Booker, a former mayor of Newark, also faced questions about this handling of police, as he sparred with Vice President Joe Biden. Biden accused Booker of hiring “Giuliani’s guy,” now-former Chicago Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy, and allowing police to “stop and frisk,” a racially biased practice that ultimately contributed to a federally mandated consent decree.

Booker defended his record, noting that the ACLU praised him for embracing needed reforms. On Thursday, a spokesperson for Booker’s campaign said in a statement that he had “inherited a city with decades of deep-seated and systemic issues when it came to police practices and the relationship between the community and the police.”

If, as critics suggest, all three mayors could have done more to rein in police, most also acknowledge that there are systemic issues that impede their ability to do so.

According to the Washington Post’s database tracking officer-involved shootings, U.S. police killed at least 992 people last year. Though some of these incidents no doubt involved excessive force, officers often escape accountability, in part due to qualified immunity, a protection from civil liability afforded to officers by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Police are also often shielded by collective bargaining agreements between mayors and their police force, Vitale said. Mayors can find themselves boxed in by police contracts that overly insulate officers from basic accountability for misdeeds, he said.

“The near-uniform excusing of abuse of force sends the message that abusive police use of force Is politically acceptable,” Vitale said, “and it says something about the diminished status of the communities that are subjected to this kind of policing.”