In Los Angeles, Police-Backed Street Cleanings are Upending the Lives of Homeless People

The city is ramping up a cleanup program that activists fear will worsen the criminalization of homelessness.

Maria Dimitriou has worked hard to make her spot on the sidewalk into a home, fitting her entire life underneath a tent and some blue tarps. She has a bin of shoes, a nightstand filled with odds and ends, and a rack of hygiene products. An artificial plant and a white teddy bear grace the entryway. But despite the small comforts of her shelter, Maria is worried that she will be displaced come 7 a.m. the next morning—at least for a few hours—as sanitation crews arrive to clear out her block in Los Angeles’s Koreatown neighborhood.

“Why should I be limited because I’m homeless and on the sidewalk?” said Dimitriou, 46, as she contemplates how to handle the impending street cleanup. She loves collecting shoes and purses, and is trying to live a full life despite being on the streets, she says. “I would get locked up if I defended my things. They look at us like criminals.”

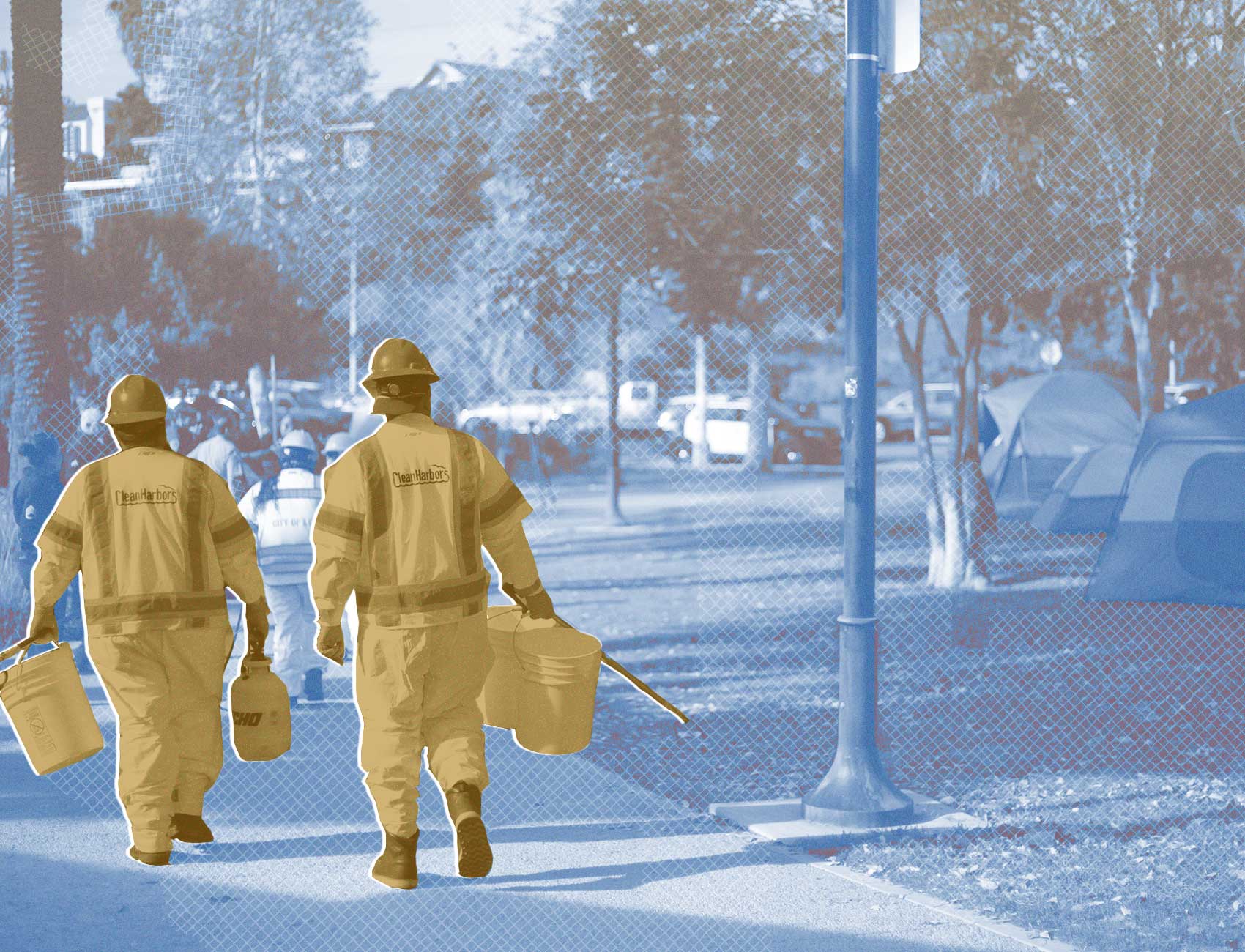

As Los Angeles’s homeless population has grown to over 36,000 people, the city is putting over $38 million into its street cleanup program this fiscal year and doubled the amount of cleanups conducted each month to about 1,600, removing thousands of tons of trash.

In the wake of complaints from City Council members that the cleaning crews are too lenient, sanitation services announced in January that they will strictly enforce the 56.11 municipal code, which allows the city to seize “bulky” possessions, and limits when and where homeless people can erect their tents. In many cases, the stricter enforcement will be backed by police, who will now pre-deploy to homeless encampments that have “documented histories of escalation or aggressive or confrontational behavior.”

“The word ‘confrontational’ could be taken for people standing up for their rights,” said Jane Nguyen a co-founder of Ktown For All, which organizes against the cleanup program. “It’s a huge setback and it does have devastating consequences for people that are living on the streets.”

Ktown For All, along with seven unhoused people and another advocacy group, filed suit against the city of Los Angeles in July, claiming that the municipal code is unconstitutional. But in February—weeks after the city announced tougher enforcement—they asked the court to issue a preliminary injunction to stop the enforcement of 56.11 while the litigation plays out. The petition, which the court has yet to respond to, says sanitation crews recently threw out three wooden pallets used by an unhoused person to “keep himself off the muddy, wet grass” and a foam sleeping pad.

Advocates are concerned about a possible increase in police involvement at a time when the Los Angeles Police Department’s uses of force against unhoused residents are up. In 2018, every 1 in 3 LAPD uses of force involved a homeless person. In the third quarter of 2019, the latest for which data is available, police uses of force against homeless people increased 26 percent compared with the same period the previous year. In January, the shooting death of Victor Valencia, who activists said was living on the streets and experiencing mental health challenges, sparked protests. Police said they mistook a bicycle part he was holding for a gun.

According to Lieutenant Yasir Gillani, law enforcement was called to 8.2 percent of encampment cleanups in December, and there are no plans to increase police presence. He added that officers embedded with sanitation crews have used force three times out of thousands of interactions with unhoused people from October through December.

Still, he says the number of use-of-force cases may rise as sanitation operations increase. “We realize we cannot cite or arrest our way out of this problem,” Gillani said.

Advocates also worry the change in policy will create more opportunities for homeless people to be cited and arrested for low-level offenses—many of which arise from basic functions of living while homeless, like going to the bathroom and sleeping. People who “willfully resist” the sanitation crews throwing away their property could face a $1,000 fine or up to six months in jail on a misdemeanor charge.

According to the most recent LAPD statistics, for the third quarter of 2019, police cited 114 people for sleeping or blocking sidewalks and 72 people for storing more than 60 gallons of personal property in public. Over 600 people were cited for either drinking in public or possessing an open container of alcohol. While those numbers represent a decrease in hundreds of citations from the same time last year, advocates worry that the trend toward fewer citations tied to living on the streets could change as sanitation crews fan out through the city enforcing municipal codes.

These low-level misdemeanors can have severe effects on unhoused people, who often struggle to appear in court and are then arrested and jailed for days on mounting misdemeanor warrants, according to multiple public defenders who spoke with The Appeal.

“What you find is the clients who have multiple failures to appear aren’t released, regardless of the underlying crime,” said Traci Blackburn, the head deputy public defender for misdemeanors at the county courthouse in downtown Los Angeles. “They have to live, they have to get through the night, and that always takes precedence over getting to court.”

Drew Havens, a member of the public defender union working in the LAX Courthouse, which sees many people experiencing homlessness in the city and other jurisdictions, said unhoused clients are jailed “every day” for failing to appear in court on misdemeanors related to living on the streets.

“Sometimes it’s literally just homelessness—from sleeping in the park, trespassing, loitering in a parking garage or begging,” said Havens.

“It has the most devastating impact on our houseless clients because they literally have nothing to go back to,” Blackburn added.

The street cleaning program was pitched last summer by Mayor Eric Garcetti as a compassionate approach to sanitation. The idea was to couple cleaning crews with outreach workers, as city residents demanded an end to mounting trash, needles, and other biohazards that can pile up at homeless encampments. But unhoused people say essential items like medicines and documents are often thrown away, while advocates say the money spent on sweeps would be better spent on providing more services like trash cans and bathrooms for the people living on the streets.

According to an announcement in late January, cleanup crews will “fully enforce” a municipal code requiring unhoused people to take down their tents from 6 a.m. to 9 p.m. and will throw away bulky items that don’t fit into a 60-gallon container.

As of now, the restrictions appear to be sporadically enforced. But the city has coupled its sanitation crew with an armada of police at Echo Park, where a tense standoff between lakeside tent dwellers and police has become the latest illustration of such cleanups. According to city code, it is illegal to stay overnight in the park. Police say the homeless individuals could face tickets or arrests for refusing to leave, though none have been arrested or ticketed so far during the current standoff. Activists say the city is using weekly cleaning crews to harass park residents in an attempt to force them out, while not offering a permanent housing solution.

“We hope you understand what this lake means to us—this has become our home in what is one of the darkest times of most of our lives,” the dozens of park residents said in an open letter to their city councilmember. “Many of us have tried to enter the shelter system elsewhere, and do not feel safe or comfortable returning to those places.”

Last month in Echo Park, police officers and park rangers appeared to outnumber sanitation workers as they kept a watchful eye over park residents dismantling their tents. “They don’t want to go into a shelter, they don’t want to go into permanent housing,” LAPD Captain Alfonso Lopez said as dog walkers brushed past. “At some point the balance shifts, where now we have to do something.”

Weeks later during a clean up Joe Losorelli, the chief park ranger, told Echo Park resident Davon Brown to “get the fuck out of here” before things escalated, according to videos shared by the Street Watch Los Angeles coalition. Brown was pinned down with a baton-wielding park ranger hovering over him and Street Watch says he was arrested on charges of battery of an officer. Los Angeles Park Rangers did not respond to a request for comment.

“The amount of resources they’ve been using to mess with people is absolutely absurd,” said Jed Parriott, an organizer with Street Watch LA, which has staged protests against the Echo Park cleanups.

Back in Koreatown, Dimitriou still remembers the day she says cleaning crews threw away a Lego set she had planned to give to her daughter. It was early morning when she scrambled to assemble her possessions, among them a broom, shampoo, and two trunks of clothes. She loaded them into a shopping cart, walked across the street and waited for the crews to finish. Eventually she returned. “Keeping my stuff organized keeps me sane,” she said. “I’m already in the street and they’re making me start over.”