Did Misconduct By A Rogue DEA Agent Nicknamed ‘White Devil’ Result In A Wrongful Conviction In A Houston Homicide?

Lamar Burks has maintained his innocence for nearly 25 years in a murder case that has been marked by conflicting eyewitness accounts and the conviction of a DEA agent on corruption charges.

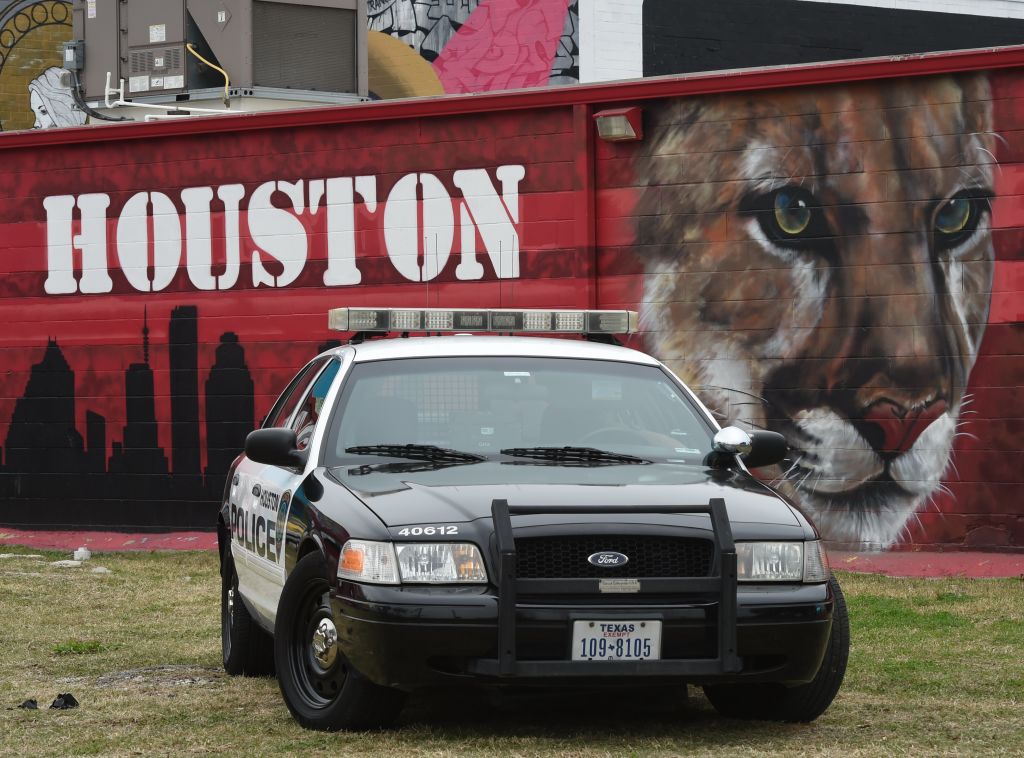

On Tuesday, the 208th Criminal Court in Houston will hold an evidentiary hearing in the case of Lamar Burks, who maintains his innocence in a 1997 killing outside a Houston nightclub.

In 2019, the Harris County District Court granted Burks a review of his murder conviction. Later that year, a Drug Enforcement Administration agent who investigated him was convicted in federal court on a slew of corruption charges. After some delays, a hearing was scheduled for April but later postponed. Meanwhile, Burks remains in the Harris County Jail— which has been called a COVID-19 “ticking time bomb.” There have been more than 1,000 COVID-19 cases connected to the jail.

Burks’s appeal didn’t gain traction until 2017 when DEA agent Chad Scott was indicted on multiple federal corruption charges. Scott investigated the murder during a sprawling federal probe that also led to the drug arrests of dozens of Burks’s contemporaries from the burgeoning ’90s Houston rap scene.

Last year, as Scott prepared to face trial in New Orleans, two witnesses provided sworn testimony that fear of the disgraced DEA agent—nicknamed “white devil”—and his partner led them to cooperate with Harris County prosecutors to pin the murder on Burks. According to Burks’s writ of habeas corpus filed last year, the two men, Randy Lewis and Clayton Brown, said they finally felt unafraid to come forward to tell the truth because Scott was off the streets.

The homicide occurred outside a Houston restaurant and nightclub in June 1997 after an argument broke out over a parking lot dice game. Houston resident Earl Perry was shot to death, and his body was found lying outside the club’s front door with bullet holes in his back and a die on the gravel nearby.

Several months later, Burks, a locally known hip-hop producer, was charged with his murder. In 1998, prosecutors dropped the charges against Burks after their initial witness said he was mistaken when he identified Burks as the killer.

But the case didn’t go away. In 2000, the district attorney’s office charged Burks again after Lewis told a grand jury that Burks shot Perry.

At trial, prosecutors told the jury that Burks and Brown got in an argument with Perry outside the club and shot him to death. In 2002, Brown entered a guilty plea to Perry’s murder. But he made a deal with former Harris County prosecutor Kelly Siegler and was sentenced to five years. Siegler, a high-profile attorney turned TV star, has come under fire in recent years after being accused of failing to disclose evidence in a death penalty case. On May 20, a federal judge ordered a new trial in that case, in which Ronald Jeffery Prible was sentenced to death for a 1999 quadruple homicide. In his ruling, the judge described a “ring of informants” in a federal prison in Beaumont, Texas, “whom Prosecutor Kelly Siegler had recruited and fed information to assist her in securing a conviction against Prible.”

Neither Brown nor Lewis took the stand to testify against Burks in his trial for the Perry shooting. Instead, the prosecutor’s sole eyewitness was Derevin Whitaker, who was originally charged in the shooting. Just before Burks’s trial, however, the charges against Whitaker were dismissed. The prosecutor in Burks’s case said Whitaker had proved his innocence. At Burks’s trial, Whitaker said he was standing nearby when the shooting happened and watched Burks shoot Perry. Burks was then convicted and received a 70-year sentence.

The stories told by Lewis and Brown are now very different. In the new affidavit, Brown says that when the argument started outside the nightclub, Perry slapped Whitaker, who had accused him of playing with loaded dice. According to Brown, Whitaker pulled out a .38 revolver and shot him to death.

A year later, Brown says in the affidavit, Whitaker was indicted on federal drug charges and became an informant for Scott. “For this reason, I have been afraid to come forward and tell the whole truth about what happened that night and identify Whitaker as the one who fired the shot that must have killed Earl Perry,” Brown wrote in his affidavit.

Brown said that a 2003 statement he made saying that Whitaker was not at the scene that night was false. He wrote, “I made the false statement because I feared for my life. I understood Whitaker was working as an informant for Scott” and his DEA partner, Jack Schumacher.

Lewis, in his new sworn testimony, backed up Brown’s account and recanted his earlier statements to the grand jury that led to Burks’s indictment. Lewis also now says he saw Whitaker shoot Perry and that Whitaker became Scott’s informant. (Last year, Whitaker signed an affidavit reaffirming that he was truthful when he testified against Burks in 2000.)

Two years after the shooting, Lewis said, Scott and Schumacher pulled him over at a traffic stop. Lewis wrote in the affidavit that the agents “threatened my life so I cooperated with them by falsely implicating” Burks in Perry’s murder. Lewis also said that Burks “was never there at the time Perry was shot.”

In August 2019, just a few months after Lewis and Brown signed the documents saying that Burks had nothing to do with Perry’s death, a jury in New Orleans federal court found Scott guilty on seven counts that included perjury, obstruction of justice, falsifying government records, and other charges. In the case against Scott, prosecutors alleged that the DEA agent ran a longtime scheme along with other federal agents and local police officers where they stole money and other property seized during drug busts. In August, Schumacher submitted a sworn affidavit acknowledging that while he and other agents “wanted Lewis to cooperate in our investigation in Rap-A-Lot Records…at no time did we direct, instruct or tell Randy Lewis to lie or provide false statements about anyone involved in our criminal investigation.” Schumacher insisted that “I have no recollection of following up on Lewis’ cooperation with State authorities in the Lamar Burks murder case.”

In January, before COVID-19 began spreading around the country, a judge ordered Scott to be brought to Texas to testify. Burks’s attorney wrote that the convicted DEA agent is “an essential material witness concerning the coerced and false testimony that precipitated [Burks] indictment and conviction.”

“Mr. Scott has been convicted of similar misconduct in the Eastern District of Louisiana,” the motion continued.

A hearing was set to occur in April. By then, the virus had shut down major activity at courthouses around the country; later, the June date was scheduled.

While he waits to confront Scott in court, Burks, who has asthma, is in the Harris County Jail and worried about being infected with the novel coronavirus. In his letter to the judge, Burks’s attorney pointed out that as of April 20, 93 people at the jail had tested positive for Covid-19.Burks and his attorneys believe he deserves to be released while his conviction is being reviewed. On April 23, his attorney wrote a letter to the judge asking that Burks be released to home confinement with electronic monitoring to mitigate any flight risk.

Harris County prosecutors opposed the motion, saying that as a convicted murderer Burks poses a danger to society.

The judge sided with prosecutors. In an order signed on April 25, Judge Greg Glass wrote, “Having considered the applicant’s request and the State’s reply, the court DENIES Burks’ request to be released on bond due to COVID-19.” The judge provided no other explanation in the order.

On May 21, Burks filed a second motion asking that his request for release due to the pandemic be reconsidered. The state once again opposed. The prosecutors repeated an argument from their earlier opposition to his release that Burks’s asthma should not be considered a factor because the condition is not a “top comorbidity” associated with COVID-19. However, the CDC has said that those with asthma “may be at higher risk of getting very sick from COVID-19.”

Scott’s conviction has led the Department of Justice to re-examine dozens of the cases the DEA agent brought during his nearly three-decade career. Since his 2019 conviction, Scott has been under home confinement in Louisiana awaiting a second federal corruption trial on more charges scheduled for December (The Justice Department and Scott’s attorneys didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment from The Appeal.)

Throughout the Scott saga, the Harris County DA’s office continued to maintain that Burks killed Perry. In November 2019, the office told the Houston Chronicle that its conviction integrity unit had thoroughly reviewed Burks’s claims and stood by its case. Asked about Burks’s attempt to get released because of the pandemic, an office spokesperson declined to comment and referred The Appeal to the court documents on the record.

As the hearing approaches, Burks has gone on the offensive against the Harris County DA’s office. He hired a public relations executive from Boca Raton, Florida, Thomas Madden. Burks used funds from his defense fund to secure the firm’s service, Madden told The Appeal. In return, Madden put out a bombastic press release on June 10 claiming DA Kim Ogg was protecting “white criminal cops.”

“The district attorney is ignoring a lot of evidence,” Madden told The Appeal. “Hopefully, there will be some pressure on the DA’s office to be forthcoming” when the evidentiary hearing is held.

Last week, each side released a witness list for the hearing. The state’s list includes notable witnesses such as Lamar Burks, his daughter, Jada Burks, Derevin Whitaker, and Scott’s former DEA partner, Jack Schumacher. Burks’ list of witnesses who may be called includes Clayton Brown, Randy Lewis, and Scott.

Burks’s attorney, Michael Wynne, declined to comment on the new filings in his client’s Burks’ case as well as the PR statements. “Cannot comment on anything,” he emailed The Appeal this week.

Asked about Burks’ claims, the DA’s office told The Appeal, “We’ll limit our comment to what we file with the court and what we say during the hearing. We remain confident in the integrity of this conviction.”