Kentucky’s Heroin Bill Was Meant to Ease the State’s Opioids Crisis; Instead It’s Increasing the State’s Prison Population

In 2013, Kentucky closed the last of its private prisons partly because of a 2011 State House Bill that moved low-level drug offenders into treatment instead of prison, through a deferred prosecution program. Fueled by the bill’s success, Kentucky’s prison population went down to 20,300 by the end of 2013, down from 21,466 in 2012. The 5.3% […]

In 2013, Kentucky closed the last of its private prisons partly because of a 2011 State House Bill that moved low-level drug offenders into treatment instead of prison, through a deferred prosecution program. Fueled by the bill’s success, Kentucky’s prison population went down to 20,300 by the end of 2013, down from 21,466 in 2012. The 5.3% drop was tied for the third highest decrease in the United States. In 2015, new legislation was enacted to increase funding for substance abuse programs, expand access to the overdose reversal drug naloxone and allow local health departments to set up syringe exchanges. “We’re coming to help you,” then-Governor Steve Beshear said, addressing folks caught up in the opioid epidemic plaguing Kentucky and the rest of Appalachia. “Work with us. Help us to help you to get on the road to recovery, and to becoming a productive member of society.”

Two years later, however, the state’s prison population has reached an all-time high of 24,600 and Kentucky is getting back into the private prison business.

What happened? The Kentucky legislature passed a law responding to the state’s opioid epidemic; the legislation was credited for taking a public health approach to opioids, but the law was also highly punitive. While the bill did provide money for treatment programs, establish some needle exchanges, and increase access to the heroin overdose drug naloxone, the 2015 law also increased the penalty for drug trafficking, which had previously been one to five years. Selling between 2 and 100 grams of heroin remained a Class C felony, but because of the bill, individuals convicted of that offense had to serve at least half of their sentences. Two new levels of offenses were also introduced for high-volume traffickers and a new crime of “Importing Heroin” was created. Selling less than two grams of heroin remained a Class D felony, but dealers charged with two “indicators of trafficking” (like having baggies on them or large sums of cash) had to serve at least half of their prison sentence.

In 2012, 881 people were admitted to Kentucky jails for Class D felonies. In 2016, the number was 1,821.

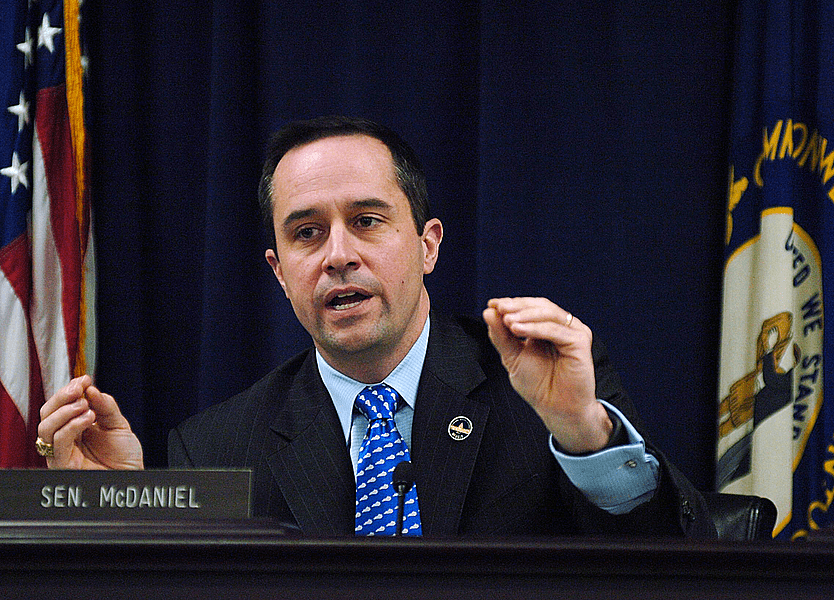

“We believe that we need to trust our prosecutors locally to make these decisions,” said GOP state Senator Chris McDaniel, as he pitched the public on the stricter sentencing in the 2015 bill, “and we trust our prosecutors.”

Prosecutorial discretion is, however, one of the major reasons that Kentucky’s attempts to reduce their prison population have been such glaring failures. Take rural Carroll County: Under the 2011 legislation’s “deferred prosecution” program, first and second-time drug possession offenders can avoid conviction by seeking treatment. But in 2016, Jim Crawford, the commonwealth’s attorney for the 18th Judicial Circuit, told the Courier Journal that he doesn’t believe in deferring prosecution because, “I lose control over the defendant and can’t keep track of what they are doing.” In 2014, Carroll County sent people to prison at a higher rate than any other US county with a population of more than 10,000 for which data is available.

The prison population in Kentucky is likely to increase again thanks to House Bill 333, signed into law in July by GOP Governor Matt Bevin. The law increases penalties for trafficking illicitly manufactured fentanyl and lengthens the sentence for those dealing or even sharing any amount of heroin, even if the defendant is struggling with addiction. Incredibly, Assistant District Attorney turned State Senator Whitney Westerfield urged passage of the bill by citing law enforcement’s sensitivity “to the need for substance abuse care.”

But this new legislation’s carceral approach simply picks up where the 2015 bill left off: Kentucky’s prison population is projected to increase by another 19% over the next decade, at a cost of $600 million to taxpayers. Despite these efforts, many parts of the state are still ravaged by heroin addiction. In 2016, overdose deaths in the state hit a record high, with 1,404 people dead. If the state’s reform strategies continue to be pushed alongside repackaged “War on Drugs” policies, we can expect things to get even worse very soon.