Joe Biden Should Use Federal Dollars to Fund Alternatives to Police

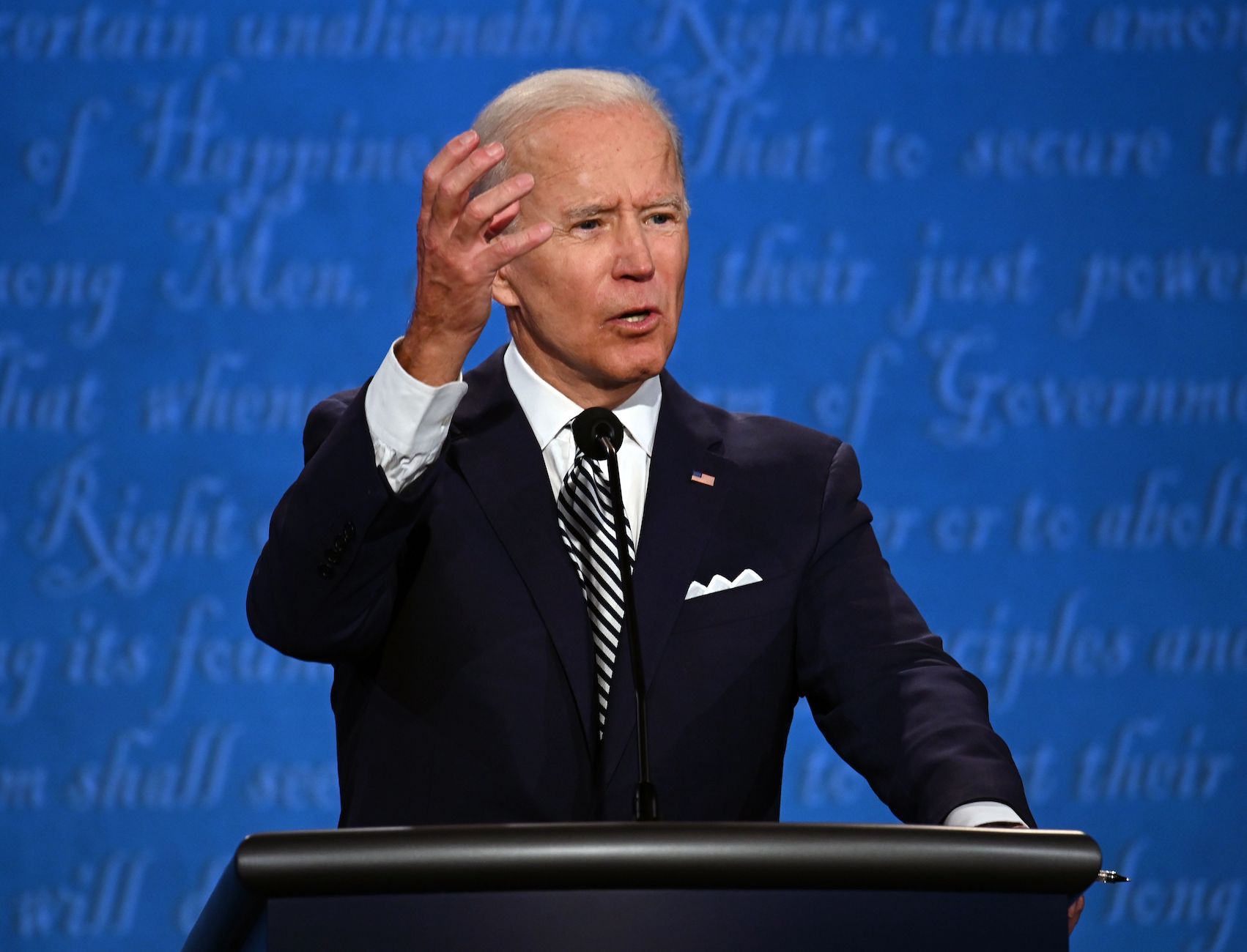

If he becomes president and Democrats win the Senate, Biden should push a federal spending bill that includes money for civilian first-responder programs.

This commentary is part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

With state legislative sessions wrapped up, it’s hard not to feel like the window for reducing the footprint of American policing, spurred by this summer’s protest movement, has closed. That’s because the federal government—even before Congress was locked in a paralyzing stasis—has traditionally played a limited role in reforming police.

The federal Justice in Policing Act, now stalled in the Senate, suggests that pattern could continue. The act intends to curb the worst excesses of policing, but it would not significantly shrink its scope. Although the act does end federal qualified immunity, it is otherwise largely toothless; it would nudge attorneys general to investigate misconduct and bolster oversight of federal officers, of which there are many fewer compared to local police.

And distressingly, Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden has also called for investing more money in the same old police reforms. This includes the kind of stale community policing initiatives that are a vestige of the post-Ferguson Obama-era Department of Justice, including increasing funding to the department’s Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) office by $300 million.

Neither Biden’s platform nor the Justice in Policing Act offer much that is consistent with building community-based approaches to public safety that activists have long sought and that many others have demanded during the recent wave of protests against police violence.

Should he win the presidency, and should Democrats reclaim the Senate in November, Biden’s administration should use reconciliation to pass an expansive spending bill that includes a federal program to fund civilian first responder programs that contain the seeds of promise for a public safety future that does not center law enforcement.

This would include trauma-informed mobile crisis teams staffed by mental health professionals—like CAHOOTS in Eugene and Springfield, Oregon—that respond to homelessness and mental and behavioral health crises. The bill could incorporate dollars to help cities set up divisions of unarmed, civilian transportation agents to enforce traffic and parking laws instead of police, like BerkDOT, the new transportation department that Berkeley, California, began creating in July. It would mean investing in public health-centered approaches to tackling gun violence, like cognitive behavioral therapy and programs like Cure Violence that exist in cities like New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore and employ credible messengers like street violence interrupters to diffuse conflict before turning to criminal enforcement.

We already have a sense of what model legislation might look like. In August, U.S. Senator Ron Wyden, an Oregon Democrat, introduced the CAHOOTS Act, which would amend Title XIX of the Social Security Act to allow state Medicaid programs to accept federal dollars to provide for community-based mobile crisis intervention services. The legislation would permit the federal government to fund 95 percent of the cost of these services for three years, as well as offer $25 million in planning grants for states to create new programs. The CAHOOTS Act would also require more rigorous national data collection by states to reduce racial and other disparities in the delivery of services and evaluate outcomes for people with mental illness when compared to a traditional law enforcement approach, which would be summarized and disseminated by the Department of Health and Human Services to promote best practices. The bill now sits with the Senate Finance Committee.

Federal dollars for alternatives to policing could easily be tucked in the broader omnibus stimulus bill that is rumored to be a chief initial legislative priority of Biden’s policy team. A Democrat-controlled Congress will have the political capital that a new majority and the reconciliation process provides to push a series of relief packages that could add up to be the largest since the Great Depression. Creating new funding streams for cities that want to create public safety alternatives fits naturally into a federally funded jobs program to combat our COVID-19-catalyzed recession and a paucity of federal income support that has left many workers in exhausted labor markets facing a crisis of long-term unemployment. It would also be timed perfectly with the beginning of the 2020-21 budget planning process that begins this fall in many municipalities.

Biden has called for a multi trillion-dollar relief package that centers job creation through infrastructure spending and economic greening; he should commit to building a new public safety infrastructure as well.

Programs that create community-based public safety alternatives are already very popular with the general public. New polling from Data for Progress and The Justice Collaborative shows that 68 percent of likely voters (and 62 percent of Republicans) support increased investment in community-based violence interruption programs. Sixty-eight percent of likely voters also support a non-police response to mental and other behavioral health crises. (The Appeal is an editorially independent project of The Justice Collaborative.)

These programs are also cheap and cost effective. CAHOOTS is funded at $2 million, about 2 percent of annual police spending in Eugene and Springfield, but saves the city roughly $8.5 million a year.

The CAHOOTS Act, unfortunately, does not require jurisdictions to divest from their law enforcement agencies. But funding this program instead of COPS or other DOJ initiatives that have had middling success would be a worthwhile commitment to moving beyond the type of police reform championed in the Obama years. Just as states opted out of the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of Medicaid, not every jurisdiction will be willing to accept the federal government’s largesse. But those that do will serve as worthwhile experiments to continue to build an evidence base (and public support) for the most effective version of these models.

If Democrats are victorious in November, they will have the opportunity to both mount a robust recovery effort in the face of cataclysmic suffering and make good on a promise to make ambitious structural changes to our existing public safety systems. They can accomplish both objectives by making community-based alternatives to policing a piece of the bold New Deal-style stimulus plan they will need to pass to pull us back from the brink.

Aaron Stagoff-Belfort works for the Policing Program at the Vera Institute of Justice. He is based in Brooklyn. His views are his own.