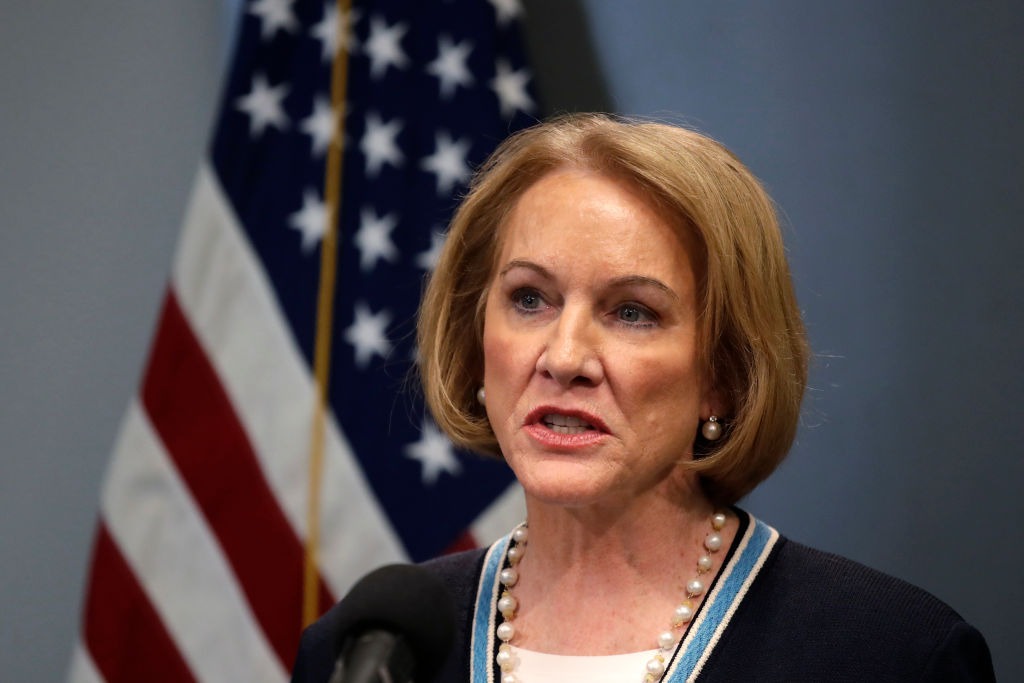

Seattle Mayor Known As ‘Tear Gas Jenny’ For Police Treatment Of Protesters Has Troubled History As A Federal Prosecutor

As U.S. attorney in Seattle, Durkan prosecuted a severely mentally ill man in a terrorism case using an informant convicted of child sex abuse—and claimed to have reformed the same Seattle Police Department that has tear-gassed peaceful protesters for weeks.

On Nov. 24, 2014, a St. Louis grand jury announced it would not indict former Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson with fatally shooting 18-year-old Michael Brown. That same day, Jenny Durkan, who had served as U.S. attorney for the Western District of Washington until that September, wrote in the Washington Post that she understood the decision because of the “high legal burden” prosecutors face when attempting to criminally charge police. Durkan wrote that she faced a Ferguson-like crisis when, in 2010, Seattle officer Ian Birk fatally shot John T. Williams, a Native woodcarver, after Birk said he saw Williams holding a pocket knife. The “knife” turned out to be a whittling tool. Despite public anger—and the police department’s own Firearms Review Board’s finding that the shooting was unjustified—Durkan claimed in the Post op-ed that her office was unable to charge Birk under federal law.

Instead, Durkan said the shooting pushed her office to reform the Seattle police. Her office and the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division conducted a “pattern or practice” investigation into the department and determined that it routinely used excessive force.

“Today both the city and the department have new leaders who have embraced reforms,” she wrote. “Years of work remain to implement the new policies and truly change the culture. But all parties—community, police, elected leaders and the DOJ—are building the type of department the city needs and wants.”

Now, nearly six years later, Durkan faces yet another crisis of policing, this time as Seattle’s mayor: Seattle police are still not in compliance with the federal consent decree that Durkan negotiated as a federal prosecutor. In May, Durkan requested the federal government terminate the consent decree. And her police department has tear-gassed protesters since the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in late May, earning her the nickname “Tear Gas Jenny.”

More recently, left-leaning Seattle residents, including some Democratic Party activists, have demanded Durkan’s resignation over the actions of the police she herself once claimed to have reformed.

In mid-July, Democratic voters in three Seattle legislative districts passed resolutions demanding that Durkan step down.

“As of tonight the @36th, @37Dems, and @43rdDems have all called on @MayorJenny to resign,” the 43rd District Democrats wrote online July 16. “Seattle deserves a Mayor who will protect our protesters and journalists from police violence and who will work to defund SPD.”

Roughly 40,000 people have signed a Change.org petition demanding that Durkan be recalled. On July 20, Nat Puff, a well-known Seattle musician, comedian, and internet personality who performs under the stage name “Left at London,” released a two-track EP online to her 174,000-plus Twitter followers titled “Jenny Durkan, Resign in Disgrace.”

Elliott Grace Harvey, a founder of the Fire The Mayor coalition that is pushing for Durkan’s recall, told The Appeal that they watched politicians and Seattle police escape accountability after the violent 1999 World Trade Organization protest crackdown and wanted Seattle residents to know they could do more to hold elected officials accountable.

“Ultimately, she is the executive of the city,” Harvey said. “When you declare a civil emergency as the mayor, you have both the prerogative and responsibility to command the police department.”

But on July 23, Durkan responded to the attempted recall petition against her in court by saying that “contrary to Petitioners’ claims, Mayor Durkan welcomes accountability and careful review of recent events from SPD’s accountability partners and the community at large. Come regularly scheduled election time next year, Seattle voters can and will hold Mayor Durkan accountable for the City’s successes and failures during her administration.”

Like mayors in other progressive cities, including Portland, where Ted Wheeler unveiled police reform in June only to find himself the target of protesters and even Trump’s federal agents who later tear-gassed him, Durkan’s predicament exposes the limits of police reform in the post-George Floyd era.

Durkan’s office did not respond to a request for comment from The Appeal.

Progressive Seattleites have been skeptical of Durkan since she was elected in 2017, largely due to her history as a federal prosecutor. Durkan, the daughter of a prominent state lobbyist, was appointed U.S. attorney in 2009 by President Barack Obama and held the position until 2014. In 2017, Seattle Weekly delved into Durkan’s record as a prosecutor and noted that in 2011, she launched what was at the time referred to as the largest series of raids on dispensaries since the state originally legalized medical marijuana in 1998. That same year, as the Washington legislature voted to expand the state medical cannabis law, Durkan co-wrote a letter to then-Governor Christine Gregoire stating that her office would continue to prosecute marijuana growers.

“The prosecution of individuals and organizations involved in the trade of any illegal drugs and the disruption of drug trafficking organizations is a core priority of the Department,” the letter stated. “This core priority includes prosecution of business enterprises that unlawfully market and sell marijuana.”

But in 2018, as mayor, Durkan instead said vacating marijuana convictions was a “necessary step to right the wrongs” of the war on drugs and that she’d seen the harm caused by cannabis prohibition while working as a prosecutor.

In June 2011, Durkan’s office announced that it foiled a terror plot by two men—Abu Khalid Abdul-Latif and Walli Mujahidh—in which they planned to murder military recruiters at a federal building in Seattle. But, as the case dragged on, his loved ones argued that Mujahidh had been living with serious mental illness and had possibly been entrapped by federal agents. Durkan later described Mujahidh as a “coldhearted, enthusiastic partner” in a “murderous scheme” led by Abdul-Latif. When reporters revealed that the handsomely paid informant in the case, Robert Childs, had been convicted of child molestation and rape, and was caught deleting text messages that were supposed to be preserved as evidence in the case, Durkan declared that it is not “saints that can bring us sinners.” In 2019, Childs was arrested again after Seattle police tested a long-ignored rape kit taken from a 12-year-old girl in 2006 and said the DNA matched Childs’s profile.

In November 2019, Mujahidh filed a pro se motion asking a court to vacate his 17-year prison sentence. Mujahidh argued that, due to his schizoaffective and bipolar disorder diagnoses, he struggled to hold a series of minimum-wage jobs and had a history of mental health issues and hospitalizations dating back to when he was three years old. In the motion, Mujahidh attached a pre-sentencing investigation which detailed his staggering mental health history, including approximately 18 psychiatric hospitalizations and an interview with his mother who described a series of bizarre behaviors that began when he was just a toddler, including opening the door of a moving vehicle.

In March, a judge denied the motion to vacate Mujahidh’s sentence.

The Mujahidh case is part of a long and troubling pattern of federal terrorism prosecutions of mentally ill defendants. In 2015, Harlem Suarez, a Florida Keys resident, was prosecuted federally for allegedly plotting to bomb a public beach. But Suarez’s family instead said he had a mental disability and was conned by a paid FBI informant. And in December 2019, New York Times and ProPublica reporter Pam Colloff raised serious questions about the conviction and death sentence of James Dailey in a 1985 murder in Florida, a case driven by Paul Skalnick, who, like Childs, is a child molester turned informant.

In 2012, Durkan launched prosecutions of Occupy Wall Street protesters accused of smashing bank windows and fighting with police on May Day in Seattle. Durkan’s office, according to the Los Angeles Times, launched a sweeping probe into local anarchists and ultimately jailed two Olympia, Washington, residents for allegedly refusing to testify against other members of the anarchist community. The two detainees, Katherine “Kteoo” Olejnik and Matt Duran, reportedly spent five months in jail, including two in solitary confinement.

In a 2014 news release announcing her departure from the U.S. attorney’s office, the DOJ said that Durkan had expanded use of civil-asset forfeiture—the long-criticized practice by which state and federal law enforcement agents can seize a person’s money or property, typically without even having to convict them of a crime. The feds said that Durkan’s office had collected at least $822 million in asset-seizures in just five years.

But when Durkan ran for mayor in 2017, police reform was a central part of her platform. “The only way to continue to make progress is to keep pushing on reforms, and to hold people accountable,” Durkan said.

After the fatal shooting of John Williams in 2010, the American Civil Liberties Union of Washington requested a civil rights probe into the Seattle police’s conduct, and Durkan’s office opened an investigation in 2011. Durkan’s office eventually found that the department had wantonly used force against people of color and that one in five instances of use of force by Seattle officers violated the U.S. Constitution. The city entered into a consent decree with the DOJ, but the ACLU and Durkan herself both labeled many of the city’s proposed reforms as “toothless” and “too vague” throughout the process. In 2018, after instituting a body-worn camera program and overhauling numerous use of force and investigatory policies, federal Judge James Robart said that the Seattle police were finally in compliance with the consent decree.

But that designation didn’t last, and the fault lay with Durkan. By 2018, she was Seattle’s mayor, and that year, the Seattle Police Officers’ Guild union negotiated a labor contract that, as Judge Robart warned, contradicted significant aspects of the consent decree. (The contract, for example, allowed arbitrators to easily allow fired problem police officers to return to the force.) During contract negotiations, 24 community groups asked Durkan not to sign the document. She did so anyway.

“If you’re concerned about public safety, we needed this contract,” Durkan said.

In 2019, Judge Robart announced that the Seattle police had fallen back out of compliance with its federal monitoring program. Despite the fact that the department is still not in compliance with federal standards, in May Durkan and the Department of Justice asked Robart to terminate the monitoring program.

“The Seattle Police Department has transformed itself,” Durkan said in a press release issued barely a month before Seattle officers began tear-gassing their own citizens. On June 3, six days after the Floyd protests began in Seattle, City Attorney Pete Holmes rescinded the city’s request. On June 5, Durkan issued a “30-day ban” on police tear gas usage—only for Seattle PD to use a loophole in that ban and gas civilians again two nights later.

Over the weekend, Seattle police tossed flash-bang grenades at legal observers and used pepper spray and rubber bullets against protesters, all in violation of a federal court order issued in June in Black Lives Matter v. the Seattle Police Department, according to the National Lawyers Guild Seattle chapter.

“The police chief can only be removed by the mayor,” Harvey, the Fire the Mayor coalition leader, told The Appeal. “There’s no mechanism for the general public or city council to do that. Everything leads back to the mayor, who is selected by the voters and can be removed by the voters.”