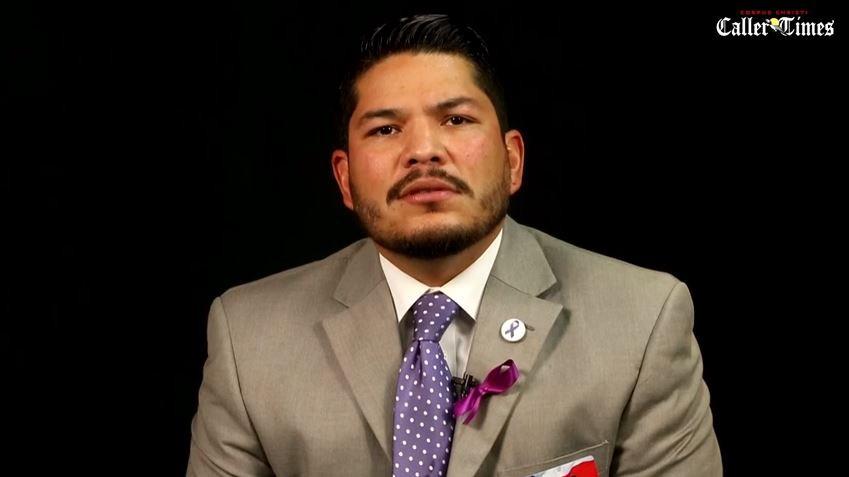

Is Mark Gonzalez The Reformer He Promised To Be?

So far, the report card on the “Mexican Biker” prosecutor is mixed.

Before his election one year ago, former public defender Mark Gonzalez raised eyebrows as a candidate for district attorney in Nueces County, Texas. A self-described “Mexican biker lawyer covered in tattoos,” including the phrase “not guilty” emblazoned on his chest, Gonzalez admitted to having more in common with the accused than with prosecuting attorneys. Campaigning against incumbent Mark Skurka, who had occupied the office for six years, Gonzalez criticized overzealous prosecutors who engaged in misconduct and wasted time and resources pursuing weak cases. He pledged to be more transparent about evidence and the district attorney’s relationship with law enforcement, to choose cases more wisely, and to facilitate dialogue with the community.

On paper, he was the antithesis of the traditional prosecutor. Coming from the criminal defense world made him an anomaly.

Gonzalez belongs to a small but growing class of prosecutors who have won elections across the country by promising to rethink draconian sentencing and curb mass incarceration. They pledge to focus on violent crimes and deprioritize low-level offenses, reversing decades-long efforts to appear tough on crime. These smart-on-crime prosecutors are a minority group among the country’s 2,300 prosecutors, all of whom have enormous discretion to charge members of the public as they see fit.

But now that a year has passed since his election, Gonzalez’ report card sends mixed signals about the future of prosecution in Nueces County.

Out of the gate, the newcomer unveiled a pretrial diversion program for people charged with marijuana possession. Rather than jail those found with 2 ounces of pot or less, the office now imposes a $250 fine and sends them to a drug class, with the option of enrolling online. Defendants who can’t foot the bill must complete 25 hours of community service. Local defense attorneys told In Justice Today that the program is “excellent” and “highly effective.” Along these lines, Gonzalez positioned himself as a district attorney who opposes tough sentencing. In May, he signed a letter reprimanding Attorney General Jeff Sessions for directing federal prosecutors to seek mandatory minimum sentences whenever possible, even for minor drug crimes.

According to Gerald Rogan, a long-time criminal defense attorney in Nueces County, the most notable change since Gonzalez took office is increased communication between prosecutors and defenders. Following up on his campaign promise, the district attorney has made himself more accessible to defense counsel than his predecessors. He is also more transparent about evidence, providing discovery in a timely manner instead of ambushing defendants during trial, Rogan says.

Despite these well-received reforms, there is reason to believe that Gonzalez isn’t fully living up to his reform pledge.

During his campaign, Gonzalez pointed to the case of Courtney Hayden as an example of prosecutorial misconduct under his predecessor, pledging more transparency under his leadership. Yet he now appears to be reneging on his promise to clamp down on prosecutors who withhold exculpatory evidence, including those involved in the Hayden case.

Hayden was tried by Jenny Dorsey, a Nueces County prosecutor under Skurka, for the fatal shooting of Anthony Macias. The alleged murder occurred after Hayden and Macies committed aggravated robbery. According to her attorney, Lisa Greenberg, Dorsey had planned to turn herself in for the robbery, and Macias was afraid that she would implicate him in the crime. He subsequently broke into Hayden’s home and cornered her in a bathroom. Hayden then fired a shot with the muzzle on Macias’ chest — a wound that indicated Hayden was defending herself, according to the medical examiner working on the case. But Dorsey’s team didn’t tell the defense about the exculpatory evidence until after Hayden was convicted and sentenced to 40 years in prison.

In June, a judge overturned Hayden’s murder conviction based on the revelation, and threw out the possibility of a retrial. But Dorsey remains on Gonzalez’ team of prosecuting attorneys, and the district attorney recently filed a notice of appeal to challenge the judge’s ruling. “I would hate to see [Gonzalez’] name behind some bad law…that says it’s OK to cheat and hide evidence. I’m hoping that he supports the idea that if you cheat, you lose,” Greenberg said.

Gonzalez told In Justice Today that he hasn’t decided whether he’ll actually move forward with an appeal. “I don’t know where I stand on it. Everything I do, I try to do it with… forethought and [look at] every single angle,” he said. “If a jury would cut her loose, I don’t care one way or another…If they walk her, I’d be fine with that. But that judge took that opportunity away from us.”

The district attorney said he’s known Dorsey for more than a decade as someone who is “honest and open” and was simply following her supervisor’s orders — hence his decision to keep her on staff. When it comes to withholding evidence, he claims things are different now. “Everyone knows that won’t be tolerated,” he said.

Greenberg applauds the newcomer for pushing reform, but remains skeptical of how far he can take his message with multiple prosecutors from the Skurka administration working alongside him. She says many are still eager to “convict at all costs.”

“It’s hard to change the mentality of some prosecutors who over-charge, or don’t see justice like you do,” she said.

Gonzalez didn’t mention capital punishment during his campaign, but he has also emerged as a prosecutor willing to pursue the death penalty at a time when his counterparts nationwide are seeking the sentence less often and public support is declining. Gonzalez appeared to be progressive in this area when he negotiated a plea deal that took the death penalty off the table for Jesse Perales, who killed his wife. But he is now pursuing capital punishment for Arturo Garza of Corpus Christi. Garza confessed to fatally battering his pregnant girlfriend in 2015, although he told police that he didn’t intend to kill her.

The Death Penalty Information Center, an organization that closely monitors executions and death sentences, reported that Nueces County was one of the 15 counties in the nation with the most executions between 1976 and 2013. But the county has been shifting away from the capital punishment in recent years, according to the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. There haven’t been any death sentences since 2010, and overall, new ones have been on a steep decline throughout the state of Texas, with only three people sent to death row in 2016. Life without parole sentences outnumber deathsentences by dozens every year, and there is a growing consensus among law enforcement and the general public that capital punishment is costly, inhumane, and riddled with errors. Gonzalez’ decision to pursue the death penalty in Garza’s case is a noticeable shift away from recent trends.

“It’s disappointing to see the district attorney in Nueces County seeking the death penalty at a time when so many prosecutors are moving away from it and juries are rejecting [it],” said Kristin Houle, executive director of TCADP.

But Gonzalez, who says his views on the death penalty “change every single day,” does not see himself as a prosecutor pushing for the most severe punishment in the modern-day justice system. He argues that Garza’s trial is merely a test case. “I’m not seeking the death penalty — I’m only presenting it to the jury,” he said. If Garza is convicted and the jury doesn’t send Garza to death row, Gonzalez says he likely won’t pursue capital punishment in the future.

Gonzalez’ record so far offers important insight into what the public should expect when self-professed “reformers” actually take office. It’s hard to gauge progress, because district attorneys choose which charges to file, negotiate plea deals, and discuss cases with other law enforcement officials outside of the courtroom and public gaze. Near-secrecy, combined with poor record-keeping, means there’s remarkably little data about the work individual district attorneys do. The metrics to determine success simply don’t exist.

But the reality is that most district attorneys aren’t the reformers they purport to be. For instance, Hillar Moore III, the district attorney in East Baton Rouge, Louisiana, claims to be progressive, but seems more interested in applaudingThe New Jim Crow than implementing meaningful reforms to end mass incarceration. In Manhattan, Cyrus Vance declined to prosecute the rich and famous — including Harvey Weinstein, Ivanka Trump, and Donald Trump Jr. — despite strong evidence against them. Meanwhile, his office aggressively prosecutes misdemeanors, and the racial disparities in conviction and sentencing rates are glaring. Until hard data is available, voters have to compare public statements with charging and sentencing decisions to measure the performance of newcomers like Gonzalez.

So far, Gonzalez appears more progressive than some, but not quite the reformer he claimed he would be. “Almost half the [voters] didn’t think I was the right person. I’m trying to earn people’s vote every single day,” the “not guilty” district attorney said. “I didn’t think some of these decisions would be so hard.”