In 2018, Activists Transformed ‘Tough on Crime’ from Asset to Liability

A series of electoral victories signals a nationwide shift.

St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Bob McCulloch was thrust into the national spotlight after Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson killed Michael Brown in August 2014. But while McCulloch faced protests for protecting Wilson in the ensuing months, he had nothing to worry about when it came to his own re-election race. He had already vanquished his primary opponent by 43 percentage points, and was unopposed in the general election. Weeks after securing a seventh term that November, McCulloch announced that Wilson would face no charges.

“On the night of the non-indictment, my prayer was that I would have an opportunity to be directly involved four years later in changing history,” recalled Reverend Dr. Cassandra Gould, the executive director of Missouri Faith Voices. “Last year, we decided that [the 2018 St. Louis] prosecutor race would be the biggest thing that we would work on this year. … We saw this race as being very pivotal in restoring hope to the community and in changing the course of history.”

The grassroots work of Missouri Faith Voices and other organizations shook St. Louis this year. In August, McCulloch lost his bid for an eighth term to Ferguson City Council member Wesley Bell, and that was just one in a series of upsets that befell entrenched incumbents this year.

While 2018 did bring significant setbacks for those who aim to reverse the country’s punitive practices—from the Trump administration’s aggressive immigration policies to the likelihood that federal and state courts grew more hostile to reform—criminal justice reformers nationwide also redefined expectations for what is achievable through local and state politics.

Organizers saw unprecedented success connecting the injustice experienced by residents with the power exercised by local officials. And some of these officials owned up to the vast authority they possess and took steps to confront mass incarceration head on, providing examples of how to circumvent these debates’ usual third rails in the future.

‘An unprecedented year of organizing’

District attorneys and sheriffs rarely face stiff competition, but something was in the air in 2018.

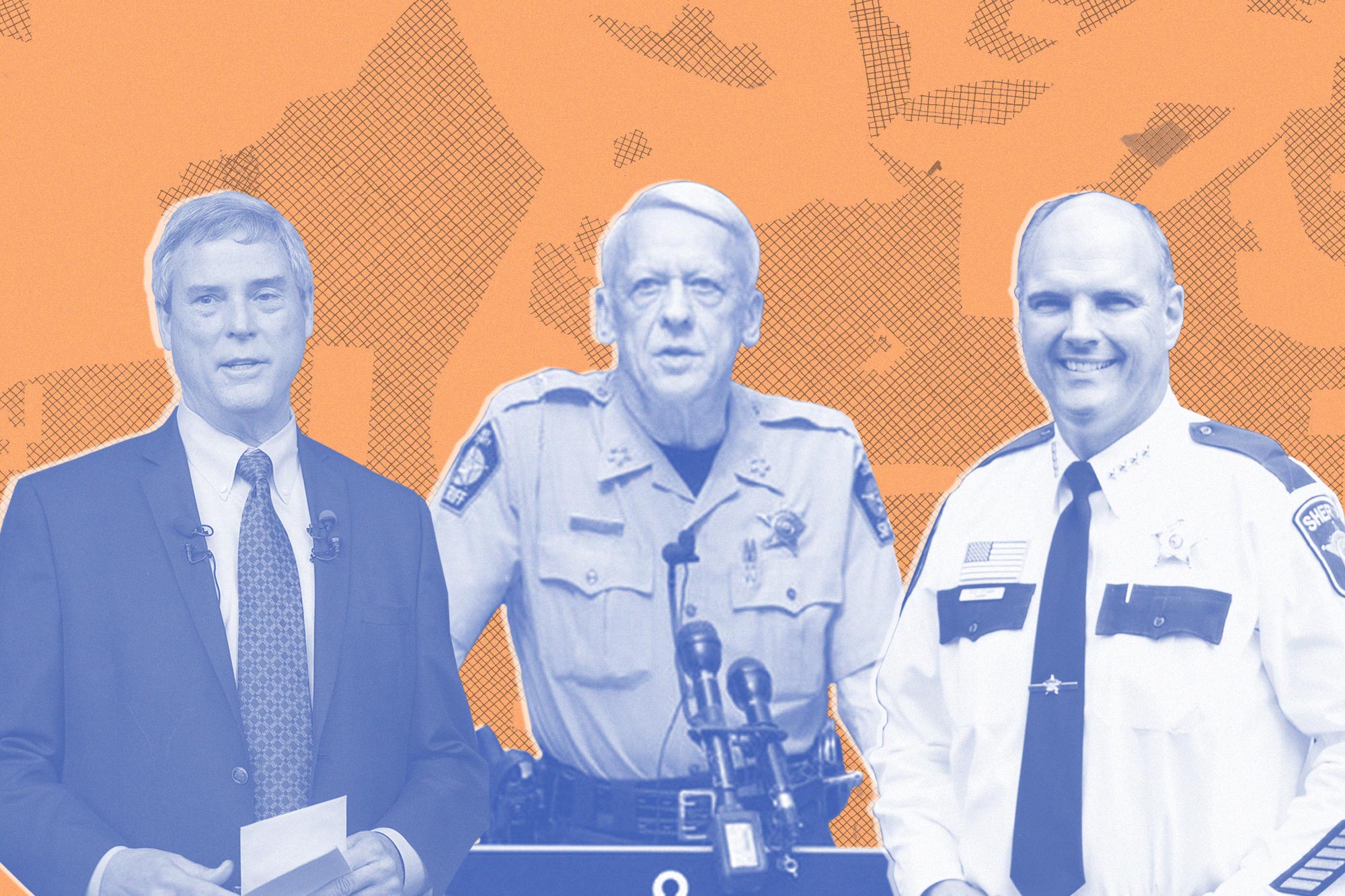

McCulloch became prosecutor of St. Louis County in 1991. Donnie Harrison, known for abusive policing practices and for targeting immigrants, was first elected sheriff of Wake County, North Carolina, in 2002. Rich Stanek, who helped ICE as the sheriff of Hennepin County, Minnesota, has been in office since 2007.

All three lost their re-election bids this year, having drawn substantial protests and community organizing against their policies. And others who lost (like the appointed district attorney in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, and Milwaukee County’s acting sheriff) were the heirs of longtime incumbents like Milwaukee’s David Clarke who had proved impossible to dislodge in cycles past.

Multiple organizers attributed these victories to broader engagement in their communities and to more receptive audiences for their arguments, as well as to renewed coordination among groups looking to transform local politics.

“This has been an unprecedented year of organizing, with different kinds of people who are not the usual suspects coming out against family separation locally,” Andrew Willis Garces, the organizing coordinator for American Friends Service Committee and Siembra NC, said of efforts to push back against cooperation with ICE in Alamance County, North Carolina. Although the county’s longtime sheriff Terry Johnson was re-elected while running unopposed in November—many officials who were cooperating with ICE outright lost in the 2018 elections—he announced soon after that he was dropping his bid to join ICE’s 287(g) program amid vocal mobilization against it.

“The vast majority [of people] are totally new to organizing, but they all have a personal relationship to the issue,” Garces added.

Similarly, Gould of Missouri Faith Voices said that participation by people directly involved in the criminal justice system proved decisive in transforming the St. Louis conversation. “People who are impacted know it’s not just their stories,” she said. “But rarely do they get to tell their story, and rarely do people care enough to listen to their story. … We were able to connect the story of their pain to their opportunity to make something different happen.”

Campaigns led by formerly incarcerated individuals, such as the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition and Louisiana’s Voice of the Experienced, also made major inroads elsewhere in the country.

Groups with different messages and tactics benefited from coordinating efforts more tightly than they had in the past, according to Gould in regard to St. Louis and Christine Neumann-Ortiz, executive director of the Milwaukee-based immigrants’ rights group Voces de la Frontera. “We created a joint platform with the reforms that we wanted to see” in the Milwaukee sheriff’s office, said Neumann-Ortiz. “That brought a broader group of people together and really united the Black Lives Matter movement and the immigrants rights’ movement. It was a solid coalition that formed to have this broader vision of change that we wanted. … There was a natural synergy. It was a galvanizing moment.”

‘Go where reforms are most needed’

The country has largely moved away from the era in which politicians compete based on who is more “tough on crime.” Many public officials now call for reducing stratospheric incarceration rates.

But this goal will remain difficult to achieve as long as reform proposals concentrate on how to deal with low-level offenses like drug possession. According to a report by the Prison Policy Initiative, a majority of the people incarcerated in state prisons have been convicted of offenses classified as violent—a reality that calls for changes still perceived as politically risky.

But in 2018, some officials signaled that it may be possible to push further in transforming the criminal justice system.

The era of trying to get away with the highest charge regardless of the facts is over.

Larry Krasner District Attorney of Philadelphia

The California legislature, for instance, narrowed the circumstances under which an individual can be convicted of murder for a homicide they did not commit and enabled existing convictions obtained under the prior felony murder doctrine to be vacated; it required that children under 16 remain in the juvenile justice system without allowing exceptions for higher-level offenses; and it reduced sentencing guidelines for individuals already convicted of some serious felonies.

“The legislature is for the first time rethinking the way we react to violent behavior,” Anne Irwin, the director of Smart Justice California, told The Appeal in October after Governor Jerry Brown signed those three bills. “That broad recognition that mass incarceration is not a good thing and is not keeping us safe is now extending to even crimes of violence.” Irwin called for policies that are geared toward rehabilitation and repair, “so that even those folks have a shot at redemption after they have paid their debts and committed themselves to changing.”

Larry Krasner, who became district attorney of Philadelphia this year, has also implemented changes to how homicides are prosecuted.

Amid national efforts to curb excessive sentencing such as the Sentencing Project’s Campaign to End Life Imprisonment, which calls for maximum sentences of 20 years, Krasner has questioned the expectation that prosecutors should pursue life without parole sentences, and encouraged filing lower charges and seeking less severe pleas. “The era of trying to get away with the highest charge regardless of the facts is over,” he told Maura Ewing in Slate. These policies follow other changes Krasner put in place after taking office in January.

“A lot of the reforms that we see around the country are not going to do much to dismantle mass incarceration,” said Ashley Nellis, a senior research analyst at the Sentencing Project. “They’re a great first step, but we have a serious incarceration problem on our hands, and Pennsylvania is a great example of that.” Nellis pointed out that 16 percent of Pennsylvania’s prison population is serving a life sentence or a sentence of 50 or more years, a number that’s partly due to the state’s mandatory sentences of life without parole for anyone convicted of first- or second-degree murder.

“If we’re serious about criminal justice reform, we have to go where reforms are most direly needed,” Nellis said in praise of Krasner’s policies.

Still, it remains a norm to carve out large categories of offenses from criminal justice reforms. In November, for instance, the New Jersey attorney general instructed law enforcement agencies to stop honoring requests made by ICE that individuals be detained beyond their scheduled release date; courts have repeatedly ruled that such requests are unconstitutional. Yet the attorney general also allowed for exceptions for individuals charged with “a violent or serious offense.” Immigrants’ rights advocates told The Appeal that these requests are no less unlawful.

The ranks of officials who shun facile distinctions between groups of defendants are nevertheless growing. “We can’t exclusively focus on nonviolent offenders,” Rachael Rollins, Boston’s incoming district attorney, wrote in a candidate questionnaire during her campaign. “We need to start having hard conversations about violent offenders and what we are doing to make sure that when they return to the community they have the tools necessary to re-enter successfully.”

What lies ahead

The interplay between emboldened organizers and the new public officials elected in 2018 will be crucial to the landscape of criminal justice reform in 2019 and beyond.

“We want to be in conversation with [Wesley Bell], and remind him of the pain of the people, remind him of why it was necessary to elect him so that things don’t stay the same,” Gould told The Appeal about the incoming prosecutor of St. Louis County. “We don’t expect St. Louis County to be run the same way in two years that it was run over the past 27 years.”

“I also believe that, even beyond the prosecutor in St. Louis County, we put elected officials on notice that the power still rests with the people,” Gould added.