North Carolina Sheriff Criticized For Unleashing K-9 Dogs On Black People Faces Re-Election

Advocates say that Sheriff Donnie Harrison is unfit for a fifth term because of such abusive practices as well as his office’s cooperation with ICE.

The Appeal is spotlighting sheriffs across the country who are seeking re-election on Nov. 6. The rest of the series is available here.

Sade Tomlinson was running scared in the woods. A K-9 dog was pursuing the Black then-17-year-old, who, along with friends, had taken off after their car crashed. But the dog’s handler, a sheriff’s deputy, said that he got caught in a mess of briars and logs, and the dog broke free, continuing its pursuit. Then the animal attacked.

“The dog ripped off my pants, so I was out there with no pants on,” Tomlinson told a local TV station. “It started attacking me, biting on my legs,” she said. The dog continued biting Tomlinson to the point where she could no longer feel her legs. “I just stopped fighting because there wasn’t anything else I could do.”

The attack on Tomlinson happened in August 2016, but it wasn’t the first of its kind that year in Wake County, North Carolina. In April, a deputy unleashed a K-9 dog on Kyron Dwain Hinton, a Black man with mental health issues. Hinton had been apprehended by police after he was found standing in the middle of a busy road. Though Hinton informed officers he was “having a crisis,” two state troopers, a sheriff’s deputy, and the police dog converged on Hinton when he failed to follow orders to get on the ground.

On dashcam audio, released to the public, Hinton can be heard crying out “Yahweh help” and “God is good” as the dog mauls him. After the attack, during which Hinton said he suffered 21 bites, a broken nose and a fractured eye socket, he was sent to a hospital and then to the county jail, charged with disorderly conduct, resisting a public officer, and assault on a law enforcement animal.

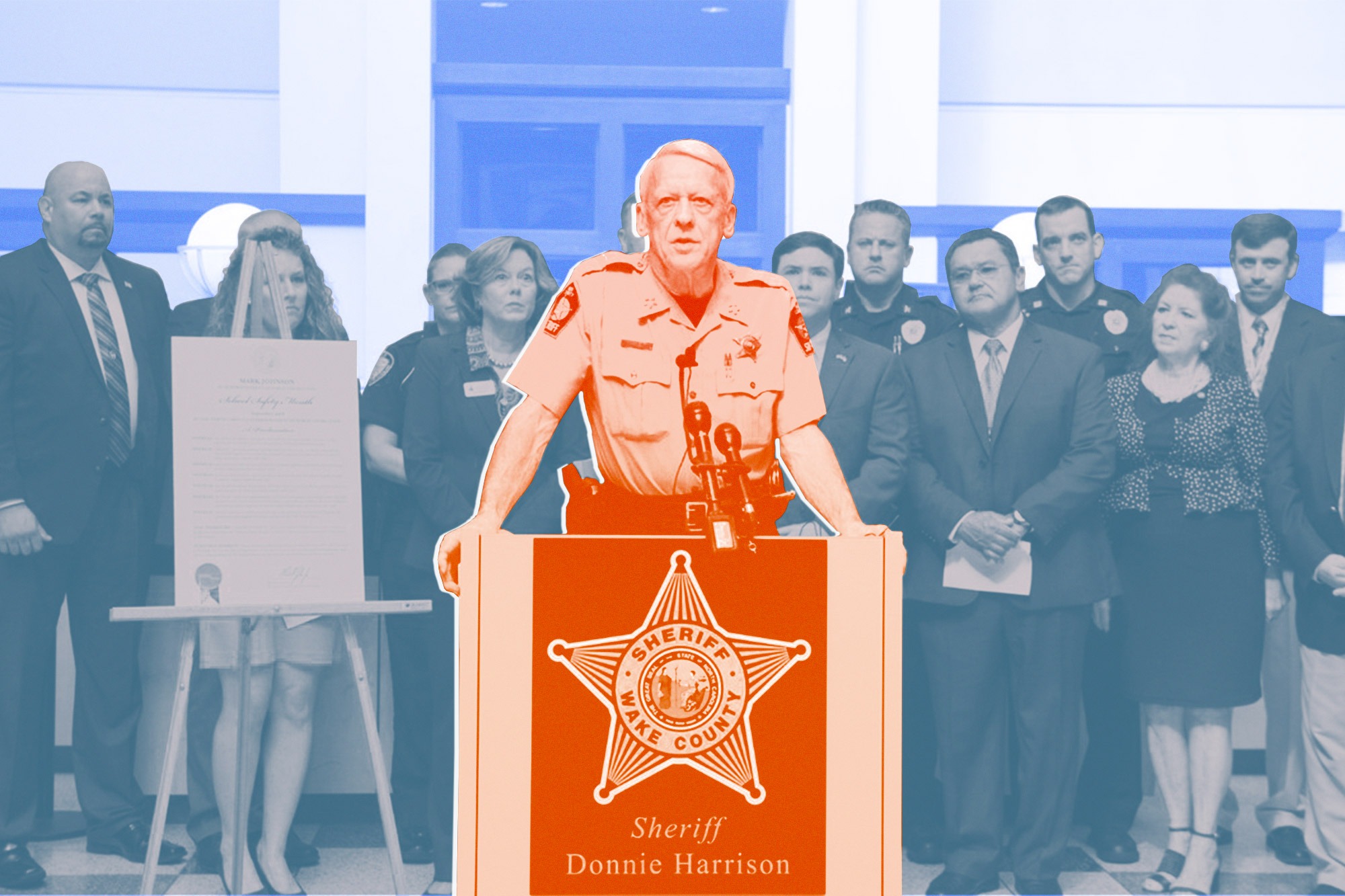

Sheriff Donnie Harrison, who has served four terms and is up for re-election on Nov. 6, was defiant after the incident. When prosecutors dropped the charges against Hinton, Harrison questioned the move, and he accused activists of trying to “exploit” the case when they raised concerns over the dashcam footage. And of Tomlinson’s case, Harrison said, “We never want to hurt anybody, but we have a job to do.”

Under Harrison’s leadership, Black residents have consistently born the brunt of aggressive policing. Though Black people are just over a fifth of the population, they account for 55 percent of use of force incidents since 2002, according Open Data Policing.

Unleashing police dogs on Black residents harks back to deeply violent days in the American South, says Rolanda Byrd, executive director of Raleigh PACT, an anti-police-brutality group. But under Harrison, she says, it is accepted as “a normal circumstance on how they [sheriff’s deputies] choose to pursue people.”

Byrd also criticizes Harrison for his opposition to a civilian oversight board, which the sheriff has suggested is unnecessary. “We try not to hide anything,” he said at a public forum hosted this month by PACT and three other community organizations. “Those of you that have been by my office know that you’re always welcome to talk to me.” But Byrd argues the board would help correct racial disparities in policing. “If you know that these things are going on, and you don’t feel there’s a need for change, there’s something wrong with this system,” she said. “The community needs this board.”

Gerald Baker, who’s challenging Harrison for sheriff, shares some of Byrd’s accountability concerns and supports a civilian review board with subpoena powers. “There’s so many issues that are going on in the sheriff’s office that you don’t know about,” he said at the forum. “And issues, when they come to play, are not being dealt with properly depending on who you are.”

Though Baker is a department veteran, he has publicly called for reforms at the Wake County Sheriff’s Office, including ending an agreement with ICE in its jails. Under Harrison’s leadership, Wake County has been one of the largest jail systems nationwide to maintain a 287(g) agreement with ICE, which allows police to screen jailed immigrants for documentation and hold any undocumented arrestees for ICE agents. Baker has spoken out against the agreement on social media and has said its “impact has been breaking up families.”

Neither Baker nor Harrison responded to The Appeal’s request for comment.

If recent electoral trends in the county are any indication, Baker could have a shot at winning the race. Wake County leaned Republican when Harrison took office in 2002, but it swung heavily Democratic in the 2016 election. And the county is big, encompassing Raleigh and over one million residents, many of whom are not white.

The race has also attracted the attention of advocacy groups. The ACLU is spending $100,000 to air an ad about both candidates that highlights Harrison’s collaboration with ICE. Another ACLU ad highlights the Hinton case, juxtaposing images of a civil rights era police dog attack with video of the K-9 dog unleashed on Hinton. Baker, on the other hand, has won an endorsement from the state’s labor confederation, the North Carolina State AFL-CIO.

And Byrd, the activist, says that locals are paying close attention to the race, particularly in the Black community. “I’ve seen a lot about it on Facebook,” she said. “A lot of people are talking about it and pushing for Baker in the Black community.”