ICE Protester to Face Trial in ‘Build the Wall’ Sheriff’s Massachusetts County

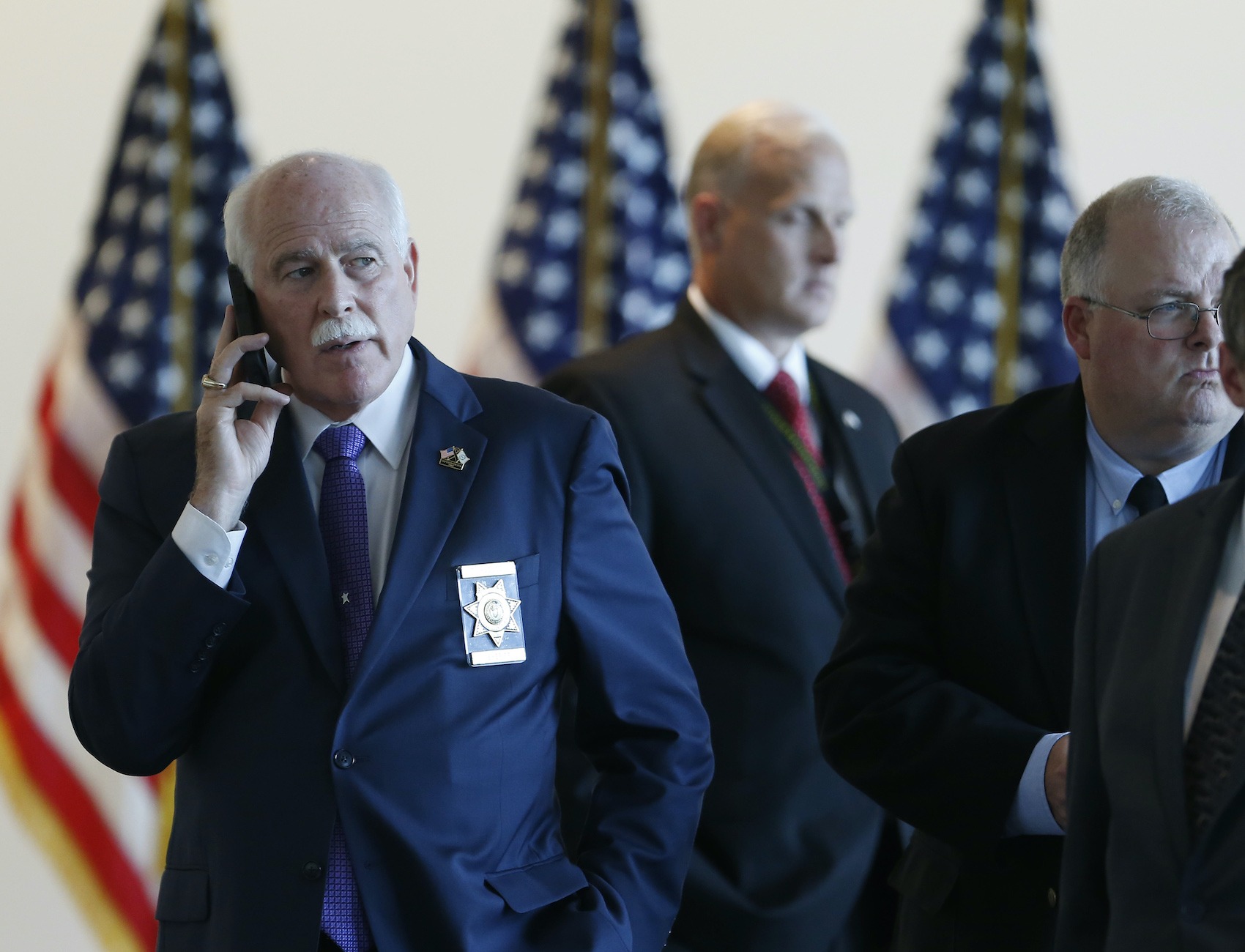

Bristol County Sheriff Thomas Hodgson, who once offered prisoners at his jails as laborers to build the border wall, is one of many sheriffs who partners with the agency.

On Thursday, Sherrie Ann Andre is scheduled to appear in a Massachusetts district court on charges of trespassing and disturbing the peace.

Roughly two years ago, Andre and others chained themselves to 30-foot tripods, blocking the entrance to the Bristol County House of Corrections. Police forcibly removed them.

The action, which was organized by the FANG Collective, a Rhode Island-based community organizing group, was meant to support more than 130 immigrants who were incarcerated at the jail and on a hunger strike. Advocacy group Families for Freedom reported that the detainees were protesting a lack of medical care for conditions like broken bones and seizures, being called “foreigners” by officers, moldy showers, rotten food, and unaffordable phone calls and commissary items. “People get food poisoning from the food and are told just drink water,” one striker told the group.

Andre faces up to 30 days in jail. Two others who blocked the entrance with Andre took plea deals and served 10 days, while another was ordered to pay $3,000 in restitution.

In an email to The Appeal, a spokesperson for Bristol County Sheriff Thomas Hodgson’s office called the action “a reckless stunt” and accused Andre and others of “putting the lives of our inmates and staff at risk.”

“If you break the law in Bristol County, you will be held accountable,” the spokesperson wrote.

Andre, who identifies as someone from a mixed-status family with Thai and Puerto Rican roots, said they feel a personal connection to what’s going on at the county’s jail.

“Those within my immediate family and my community, particularly the Southeast Asian community would be detained at the Bristol County House of Corrections, as it is one of the closest facilities [that incarcerates immigrants] to Providence, Rhode Island, where I live,” Andre said.

Bristol is one of three counties in Massachusetts that has signed a 287(g) contractual agreement with ICE, which means local authorities can be deputized to act as immigration officials within their jurisdiction. The most common form of the agreement, the jail enforcement model, allows officers to interrogate and hold arrested individuals thought to be subject for removal. Massachusetts, Arizona, and Georgia are the only states that have contracts between their statewide corrections departments and ICE’s 287(g) program.

The program was passed as part of a larger immigration bill in 1996. In 2006, appropriations for the program amounted to $5 million, then grew to $15 million in 2007, $42.1 million in 2008, and $68 million by 2010. At its height in 2009, the program had 77 agreements. After pressure from immigration advocates and high-profile cases of racial profiling, the number of active agreements had decreased to 34 by the end of 2016.

During President Trump’s first month in office, he signed executive orders calling for an expansion of the program and ICE signed 25 new agreements with county and state governments in 2017, nearly doubling the 34 agreements that were active when Barack Obama left office. As of Nov. 27, 2019, there were 90 287(g) agreements in 20 states.

Huyen Pham, a law professor at Texas A&M University, summed up the 287(g) trends in the Trump era in a paper published in the Summer 2018 issue of Washington and Lee Law Review. “In essence, the program will be a supercharged version of what operated under Presidents Bush or Obama, with few federal controls and little federal interest in those controls,” she wrote. “The end result will be the magnification of the program’s flaws as it operated in previous iterations, on a larger scale and reaching more jurisdictions.”

In Massachusetts, Democratic legislators, who have a veto-proof majority in the House and Senate, have repeatedly ignored or killed the Safe Communities Act, a bill that would ban 287(g) in the state.

“As long as the Massachusetts legislature continues to punt, they are being complicit in Trump’s racist deportation agenda,” Jonathan Cohn of Progressive Massachusetts, an organization that supports the bill, told The Appeal: Political Report last year. “Inaction is the result of a legislature and leadership that is unrepresentative of the diversity of the state.”

Intergovernmental Service Agreements (IGSA) in Bristol, Franklin, Plymouth, and Suffolk counties also allow the state to confine immigrants in their county jails in exchange for money from the Department of Homeland Security and ICE. It’s unclear whether Massachusetts has profited off its detainees. In April 2019, the state House killed an amendment proposal introduced by Representative Antonio Cabral of New Bedford that sought transparency.

Andre told The Appeal they are trying to leverage power by bringing attention to the fact that 287(g) and IGSA contracts can be terminated by either contractual party at any time.

But Hodgson, the Bristol County sheriff, is one of the programs’ most enthusiastic proponents. In an email to The Appeal, a spokesperson for Hodgson’s office said it will not only continue its ICE partnership “despite the outcry” from Andre, but is also “open [to] increasing collaboration and teamwork with ICE and other local, state and federal law enforcement agencies.”

An honorary chairperson of Trump’s re-election campaign, Hodgson once offered people who are incarcerated in Bristol County jails as laborers to build Trump’s wall. “I can think of no other project that would have such a positive impact on our inmates and our country,” Hodgson said during his fourth inauguration in 2017.

Hodgson has also been in frequent contact with Stephen Miller, the senior adviser to the president who spearheaded the administration’s family separation immigration policy. In August 2018, Hodgson sent Miller an email alerting him to Andre’s action.

The sheriff has justified the 287(g) program by claiming that immigrants are endangering the community. During a legislative hearing for the Safe Communities Act, he testified: “This bill trades the safety and security of our citizens and legal residents for the comfort and concealment of criminal illegal immigrants.”

But a study published in June 2019 from the University of California, Davis, found no connection between deportation and any kind of crime. Hodgson also blames MS-13 gang activity on immigration. However, formerly incarcerated people have said that Hodgson’s jails exacerbate such activity. “Kids are not in gangs when they come in, but they are when they leave,” a person formerly incarcerated in a Bristol County jail told the Sun Chronicle.

Bristol County holds 13 percent of the jail population in Massachusetts and accounts for 25 percent of jail suicides in the state. “Bristol County House of Corrections is just not a good place, and people don’t realize that since it is in a quote-unquote liberal state,” Andre said.

Ultimately Andre hopes that their case and trial will bring attention to conditions in the jail, and shed light on how police treated them during the action.