In a Louisiana Parish, Hundreds of Cases May Be Tainted By Sheriff’s Office Misconduct

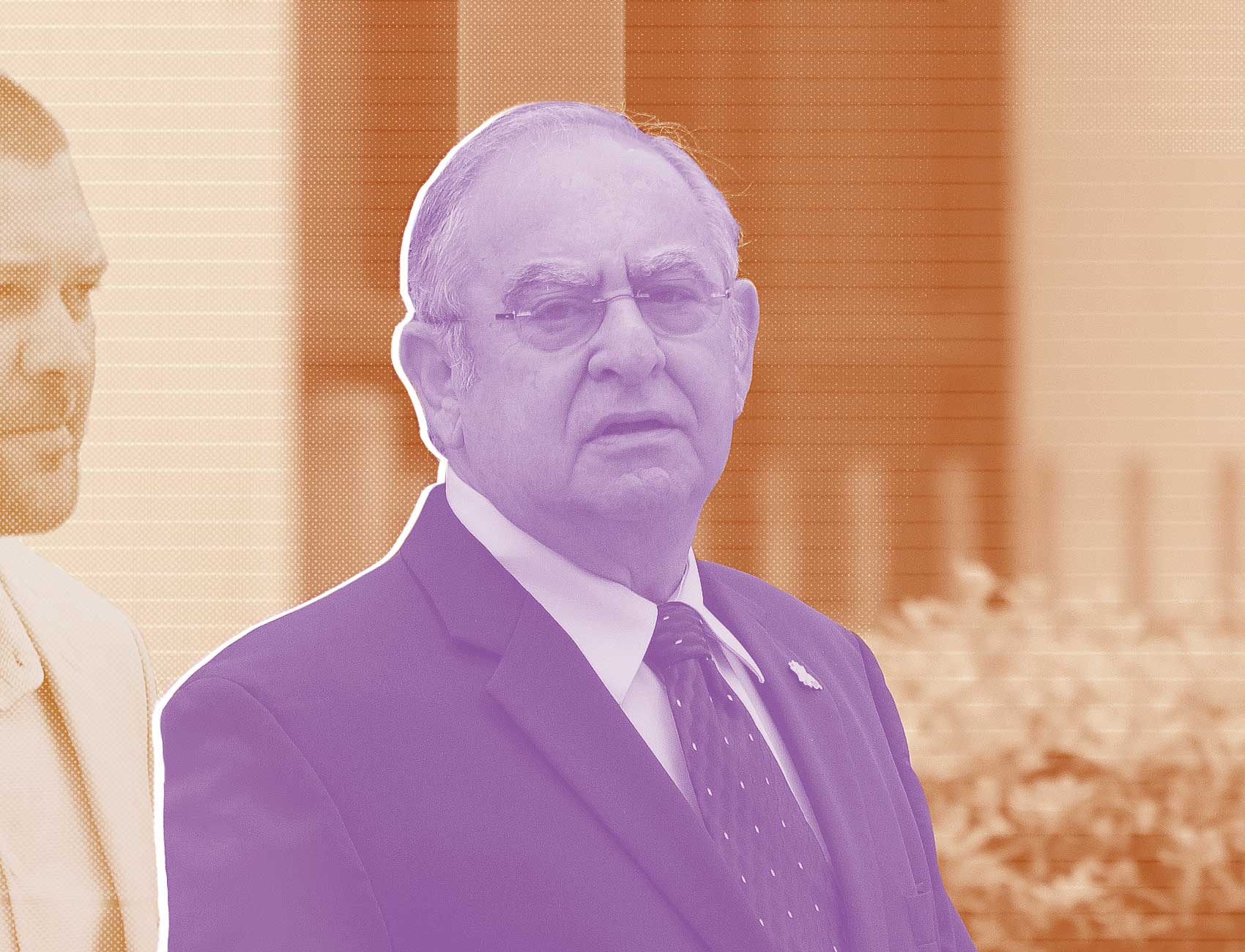

During the tenure of Iberia Parish Sheriff Louis Ackal, deputies assaulted and harassed men inside the parish jail. Several deputies were convicted in federal court, and now cases brought by the office are under renewed scrutiny.

More than 700 cases filed by the Iberia Parish Sheriff’s Office could be affected by a sprawling federal case involving departing Sheriff Louis Ackal and dozens of members of the office, according to documents obtained by The Appeal.

In “Brady letters” to defense attorneys from the district attorney of Louisiana’s 16th Judicial District, which includes Iberia Parish, first assistant district attorney Robert Vines wrote that during the federal investigation into Ackal it was discovered that several of Ackal’s former employees “engaged in improprieties and criminal activities while employed” with the sheriff’s office.

Vines told The Appeal that Brady letters were sent to defense attorneys in all cases brought by the sheriff’s department during Ackal’s tenure, which began in 2008. He said pending cases brought by the department were reviewed by his office and they declined to prosecute any pending cases where there was no independent corroborating evidence beyond deputy testimony. Vines said that a similar review was conducted for any case that had already resulted in a conviction.

In March 2016, Ackal and former Lt. Col. Gerald Savoy were indicted on federal civil rights charges related to the beatings of five pretrial detainees in April 2011.

Former deputies Jeremy Hatley, Bret Broussard, Robert Burns, Wesley Hayes, Jesse Hayes, Jason Comeaux, David Hines and Byron Lassalle all pleaded guilty in federal court between February and March 2016 to charges that included felony deprivation of rights under the color of law and making false statements.

In February 2016, former deputy Wade Bergeron was convicted of felony deprivation of rights under the color of law and later sentenced to 48 months in federal prison. In October 2016, Savoy was convicted of deprivation of rights; he was later sentenced to 87 months in federal prison. In November 2016, Ackal was acquitted on all counts in his case.

All of the guilty pleas and convictions of sheriff’s office employees stemmed from assaults at the jail and subsequent cover-ups.

Vines’s Brady letters—named after U.S. Supreme Court’s Brady v. Maryland decision, which requires prosecutors to disclose material that might help the defense, including information that undermines the credibility of state witnesses—concern cases brought by the sheriff’s office between late 2002 and early 2018. Most of the cases were brought between 2011 and 2016 and involve drug possession or distribution charges. However, arrests in at least one murder, an attempted murder and other violent crimes are also now under renewed scrutiny because of the office’s misconduct.

Because the deputies were charged and convicted, this information is required to be turned over to defense attorneys under the Brady rule and can be used to call into question their credibility in all of the cases they were involved in even if the cases were not directly related to the assaults.

More than 100 criminal cases brought in the Ackal era have already been thrown out as a result of the federal investigation. Ackal did not seek re-election in November and told The Advocate “I’m done. I’m beat up. I’m tired.” In January, he will be replaced by Tommy Romero.

Ackal did not respond to The Appeal’s request for comment.

Despite efforts by some district attorneys, like Larry Krasner in Philadelphia, to formalize lists of officers with histories of misconduct, many prosecutors fail to track or disclose these issues. Without these Brady disclosures, it is possible for officers with a pattern of dishonesty to continue making arrests under dubious and sometimes unlawful circumstances—and testify in court. One defense attorney recently told The Appeal that prosecutors who fail to track and disclose when an officer has a history of lying represents a “practice of sweeping police officers with credibility problems under the rug.”

During Ackal’s tenure, the sheriff’s office was mired in scandal and paid out more than $6 million in settlements in federal civil rights lawsuits.

In Ackal’s 2016 trial, witnesses described beatings, deputies who nicknamed a baton after a man they had beaten, and excessive force routinely used against Black people. Bergeron testified that a supervisor once told him that he and a group of deputies needed to inform Ackal that they beat two Black men. Bergeron said he was relieved by Ackal’s response: “His remark was it sounds like a case of n— knockin.”