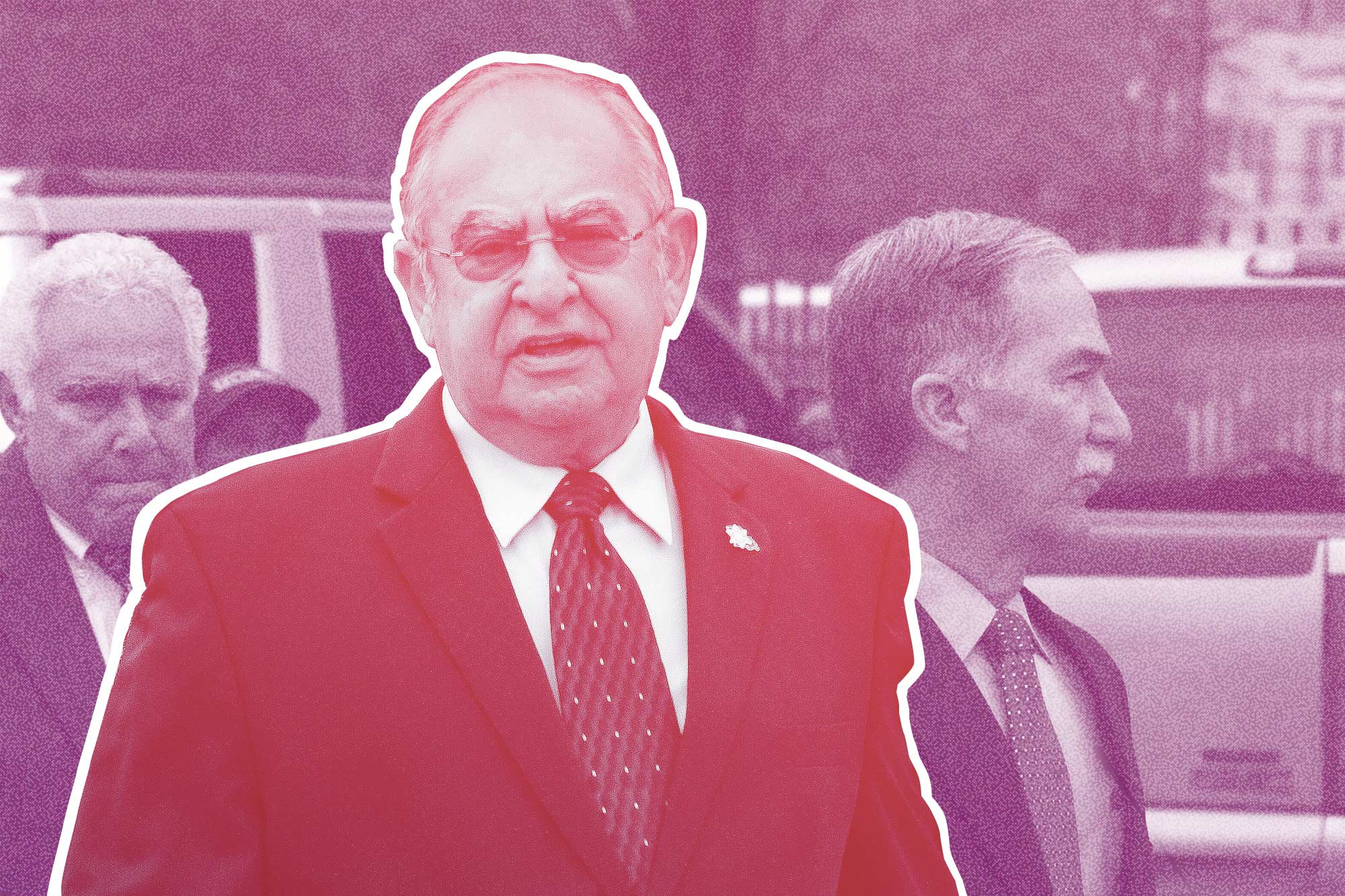

An Infamous Louisiana Sheriff Is On His Way Out. Now What?

Louis Ackal has said he isn’t seeking re-election. But advocates fear that may not be enough to bring change.

Derrick Sellers, a 33-year old U.S. Marine veteran, can no longer see properly and suffers from the headaches and disorientation associated with brain injuries sustained during war. But Sellers said he didn’t get these injuries while serving overseas.

According to court documents, Sellers was housed at the Iberia Parish jail in Louisiana in September 2013 when, one evening, a guard forced him and a few other detainees to kneel in a visiting room with their noses against the wall and their hands behind their backs. Sellers, who had a pre-existing back problem, lay down. When he eventually got back up, a group of guards and a lieutenant pinned him down and beat him over the head. They sprayed mace in his face. They hit his face with their hands, feet, knees and metal objects. They broke his left cheekbone all the way into his eye socket.

After the attack, Sellers went to the hospital, and when he returned to the jail, he says, he was placed alone in a cell, without his medications and given only a liquid diet. After his release, he filed a lawsuit against Sheriff Louis Ackal individually and as the sheriff in charge of the jail, along with the warden of the jail, and unnamed deputies who participated in the attack.

In February this year, Sellers settled with the Iberia Parish sheriff’s office for $2.5 million, the largest payout so far for an office that has been sued dozens of times, many of those over injuries caused by deputies assaulting people housed in the parish jail.

Ackal isn’t personally liable for these costs. Instead, they are covered by the Louisiana Sheriff’s Law Enforcement Program, which has now paid out over $6 million just for Ackal’s office. (One lawsuit settled for an undisclosed amount, so the total is most likely higher). Ackal has cost the program so much money that he was kicked out in 2016, the same year he was acquitted of federal civil rights charges for similar conduct.

In an email, Ackal said the $6 million figure was inaccurate, because “the insurance companies refused to try the cases” even though some were winnable, he said.

Ackal, who had previously said it would be “a cold day in hell” when he resigns, told The Advocate in 2018 that he didn’t intend to run in the October 2019 election. “I’m done. I’m beat up. I’m tired,” he said in an interview, though the candidate registration deadline has not yet passed.

Still, it’s unclear whether his departure would bring true change to Iberia Parish. So far, the only candidate who has announced a run is Roberta Boudreaux, who challenged Ackal in the last election and got 44 percent of the vote. Boudreaux worked for the Iberia Parish sheriff’s office and was the warden of the jail before Ackal came into office. Though Boudreaux is seen as a viable candidate, some critics say her track record as warden was flawed and aren’t sure she can turn around the long-troubled office.

The repercussions of a sheriff like Ackal are bound to last longer than his term in office. Advocates say that thinking a simple change of the guard will make everything better is part of what caused the problems in Iberia Parish in the first place.

“This does not exist in a vacuum,” said Leroy Vallot, a local activist. “People have not been held accountable.”

Though sheriffs are powerful in most states, in Louisiana they have amassed an unusual amount of political might. According to the 1974 Louisiana Constitution, sheriffs are the highest law in the land as the “chief law enforcement officers.” That means sheriffs are not “subordinate” to any other office, as Sheriff Jeff Wiley of Ascension Parish framed it in a video produced by the Louisiana Sheriffs’ Association.

This has sometimes been taken to mean that there is no law enforcement official who can police the sheriff. And it often means that the sheriff feels empowered to investigate cases anywhere in the parish—even if there is a local police department.

Iberia Parish, home to roughly 72,000 people, has a long history of sheriffs and their employees who abused their power. Gus Walker, a high-ranking deputy during the 1940s known as “Rough House Walker” and “Killer Walker,” took over during a time when white people in the parish were concerned about the growing power of Black residents and their demands for the repeal of Jim Crow laws.

Walker was accused by the FBI of beating and abusing Black community leaders as a way of intimidating them. Under the direction of then-sheriff Gilbert Ozenne, he used his position to drive away Black leaders who might foment dissatisfaction with white supremacy or encourage protests. It was, in the words of a Louisiana man quoted in Race & Democracy: The Civil Rights Struggle in Louisiana, 1915-1972 by Adam Fairclough, a way “to prevent the blacks from getting the upper hand.”

The parish police department has also been plagued by allegations of racism and abuse. The city disbanded the department as a cost-saving measure, and in 2004 contracted with the Iberia Parish sheriff’s department to police the streets. But the sheriff’s department has proved just as problematic, advocates say, especially since Ackal took the helm.

Ackal came into office in 2007 on a reformer platform, promising to bring integrity to the office and root out corruption. A native of New Iberia, he had been a state trooper and served in Louisiana state government before he retired to Colorado, which gave him a worldly appeal, according to advocates, in the eyes of the parish electorate. Ackal came out of retirement, he said, when he heard about the problems in his beloved hometown.

But Ackal quickly courted controversy. One of his first moves was to dissolve the internal affairs unit for the whole department. Almost as quickly as he came into office, he made his mark not just with his personality—plain-spoken, back-slapping, tough-talking—but also the frequent violence his deputies inflicted onto the parish’s residents, especially Black ones.

In 2010, Ackal’s office launched the IMPACT squad, an operation in which deputies patrolled the streets of New Iberia’s Black neighborhoods, purportedly to reduce crime, and made frequent and violent arrests. (By 2016, the squad was disbanded.)

Ackal was also known for tactics similar to those of Joe Arpaio, the Arizona sheriff who was found guilty of criminal contempt by a federal court (and pardoned by President Trump). Like Arpaio, he demeaned his detainees. In Ackal’s case, he denied them ice in the summer, forced them to wear pink, and joked about them to the press.

But there were far more serious allegations. In 2014, Ackal’s office claimed that Victor White III had shot himself to death, while handcuffed, in the back of a police car. White’s father, a pastor who had clashed with Ackal before, and his family sued, and recently settled for an undisclosed amount.

In 2014, Whitney Paul Lee Jr. was also in Iberia Parish jail. Deputies took him, along with a group of other detainees, outside where they were strip-searched and forced to kneel. Lee struggled to breathe, and deputies beat him with a baton and fired a beanbag round at his leg. Lee’s family sued and settled; his case was among those investigated in the federal lawsuit against Ackal.

Almost as soon as Ackal took office, federal investigators stepped in to examine his policing of New Iberia and the conditions at his jail. The 2016 federal trial against Ackal publicly revealed the extent of the violence and cover-up. Deputies estimated that they had beaten people over 100 times. Ackal, they said, endorsed and promoted a culture of racism and violence.

But Ackal emerged unscathed. In 2016, he was acquitted by a federal jury, got his gun back, and returned to work, vowing to fire the “rogues” who gave his office a bad name. Seven deputies were later found guilty of abusing prisoners and sent to prison; one staffer was fired after working with the FBI on the investigation against Ackal. And another deputy, James Andrews, was investigated for putting his hands around a suspect’s throat.

A few months before Ackal’s acquittal, the insurance pool that includes 45 sheriffs’ offices in the state kicked him out because he was costing too much. His expulsion letter said that his office was responsible for a third of the losses over the previous five years, or over $3 million.

Bo Duhe, the Iberia Parish district attorney, has also dismissed at least 18 cases—identified by the St. Mary Project, a nonprofit advocacy coalition that reviewed 500 cases in Iberia Parish—because they involve sheriff’s deputies accused of corruption.

Though some advocates welcome the election as an end to Ackal’s reign, it’s unclear whether a candidate like Boudreaux would turn things around. “I differ from Ackal because I’m bonded with ALL facets of the community,” she wrote to The Appeal via Facebook. “Training and community relations will be of the utmost priority in my administration. A predetermined disposition when responding to calls will not be tolerated. Each call will be handled on its own merits to ensure that the public is treated fairly.”

Even with the coming election, advocates say, the structure that empowered Ackal won’t change. “It’s so much deeper than just Ackal,” said Vallot, pointing out that local and state officials could have stepped in and didn’t. “They knew he was doing things wrong.”

Community activist Khadijah Rashad was equally dubious about the potential for change, pointing to the history of Louisiana sheriffs. “They don’t have to abide by rules and regulations,” she said. After all, she said, Ackal is leaving office without a conviction or even a serious blemish on his record. “He gets to ride into the sunset. … People were terrorized and bullied, and he gets a clean slate.”