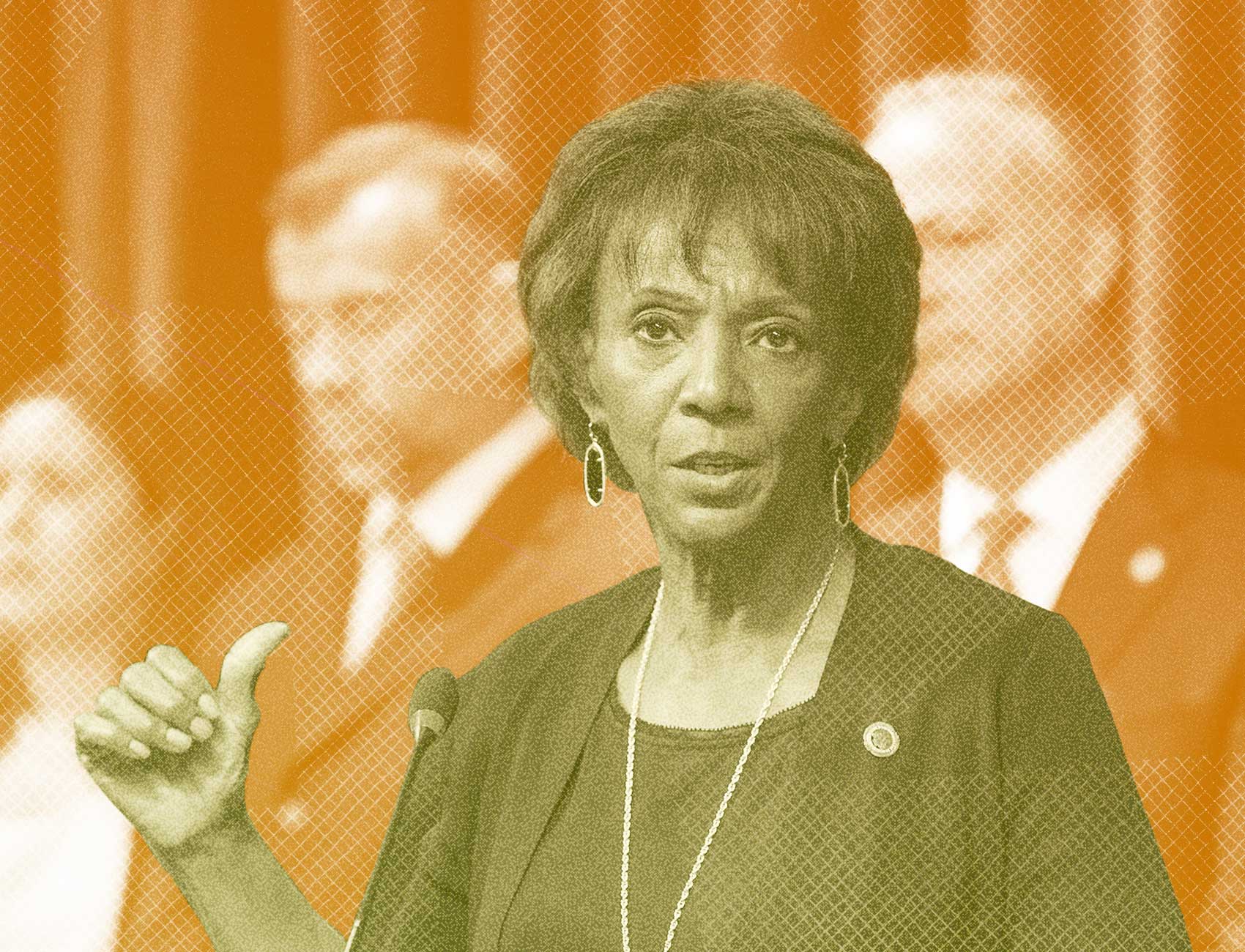

How District Attorney Jackie Lacey Failed Los Angeles

On a host of issues—including police shootings, bail reform, marijuana legalization, and the death penalty—critics say Lacey, once seen as a reformer, has sought to preserve the status quo.

On the night of May 5, 2015, 29-year-old Brendon Glenn was ambling along the Venice boardwalk with his leashed pit bull mix when two uniformed Los Angeles police officers responded to a call reporting a “Black male transient … no weapons.” According to the official police report of the incident, Glenn “appeared very irate” as the officers approached and threatened them with his dog. Body cameras captured Glenn yelling at the officers.

The officers decided Glenn wasn’t “intoxicated to a level where he was unable to care for himself,” so they watched him move on down the street. According to the report, the officers observed Glenn yell at patrons going into a bar and get into a shoving match with a bouncer, which was captured on security footage. The officers then grabbed Glenn, pulling his arm behind his back to detain and arrest him. Glenn allegedly resisted, and the officers shoved him to the ground, kneeling on his back and pulling his arms to cuff him. Glenn pulled away and, according to Officer Clifford Proctor, reached for Proctor’s partner’s gun holster. Officer Proctor fired a round at Glenn; then, noting that Glenn “did not appear to be effected [sic],” fired another round into his body. Glenn was taken to a hospital and died shortly after midnight.

Glenn was one of 25 people shot by Los Angeles police officers in 2015. According to the best available data, the number of Los Angeles Police Department shootings has been on the decline: From 2010 to 2014, police in Los Angeles County shot and killed 375 people, one every five days, according to The Guardian, or over 75 per year. In 2018, LAPD officers shot and killed 15 people. LAPD Chief Michel Moore has touted this as progress and emphasized improved de-escalation training, a technique recommended by the Police Commission, the department’s civilian review board.

But, for many, the number isn’t low enough. Los Angeles still leads the country in law enforcement shooting deaths. And last year it had the second-highest death toll for police shootings in the nation after Phoenix, which had 21. Black residents are disproportionately victims—24 percent of the deaths but only 9 percent of the county’s population. And since 2000, only one member of law enforcement has been charged for killing a civilian.

In Glenn’s case, the LAPD report and video of the incident both failed to show that he was reaching for anyone’s gun. Glenn’s hand was on the opposite side from the officer’s holster, and the report notes that “at no time during the struggle can Glenn’s hand be observed on or near any portion of Officer [redacted]’s holster.” The police chief at the time, Charlie Beck, called for Officer Proctor’s arrest and prosecution.

But on March 8, 2018, after a two-year investigation, Jackie Lacey, the district attorney of Los Angeles County, announced that she would not prosecute because she couldn’t prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt. In an email to The Appeal, Lacey said: “If a peace officer’s conduct rises to the level of a provable crime, my office will file criminal charges.”

Since taking office in 2012, Lacey hasn’t charged a single LAPD officer for a shooting. According to Black Lives Matter LA, over 400 people have been killed by law enforcement or died in custody in the county during Lacey’s tenure. But she has charged only one man, Luke Liu, a deputy in the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, for shooting an unarmed man while on duty.

When Lacey was elected, voters expected support for reforms and a healing of the historical racial divisions in Los Angeles. She told the voters during her first campaign that she grew up admiring Martin Luther King Jr. and Abraham Lincoln. Her election was enthusiastically greeted by celebrities like the music producer Sean Combs and the retired NBA player Magic Johnson. But with Lacey now in her second term, many former supporters are disappointed. What happened to the progressive candidate?

Jackie Lacey grew up in the Crenshaw district of Los Angeles with hopes of becoming a schoolteacher. Her childhood was working-class: Her father cleaned lots for the city’s public works department, and her mother worked in a garment factory. She joined the Los Angeles DA’s office in 1986. As an assistant prosecutor and later as chief deputy, Lacey, then the mother of two young children, started in code enforcement “which allowed her some flexibility,” the Los Angeles Times noted in 2012. In that role, she met Steve Cooley, then chief deputy DA, and began to try cases under his supervision.

As a career prosecutor who rose to be Cooley’s chief deputy when he was DA, Lacey got by without making waves. She was known for her collaborative, collegial style. These were the years before progressive prosecutors were gaining media attention, but the LAPD was operating under strict scrutiny after the Rampart scandal, the discovery of ongoing corruption within the police unit that covered the LA neighborhood known as Rampart. Cooley became the district attorney in 2000, winning the election against Gil Garcetti, who had lost both the O.J. Simpson and the Rampart cases. Cooley was re-elected twice before he retired. (Cooley also ran for the attorney general of California against Kamala Harris and lost.) One of Lacey’s first leadership roles was revamping the Central Trials Division, the same office that lost the Simpson trial.

Cooley’s policies were designed to restore trust in law enforcement. For example, long before California voters reformed its Three Strikes law, Cooley, who was a registered Republican, implemented an office policy not to seek the maximum (25-to-life) sentence if the third “strike” was a nonviolent offense, like theft. (Lacey would later support Proposition 36, which codified changes to Three Strikes.) Cooley also created a Public Integrity Division and gave that department independence.

His tenure wasn’t without problems. In 2009, the county’s deputy prosecutors filed union grievances against Cooley’s office for alleged retaliation, namely demoting deputy DAs who joined the union. Lacey originally testified in a hearing that she had told a friend in the office that Cooley disliked the union and that joining it would be a “bad idea.” (In an email to The Appeal, Lacey declined to comment on this incident.) Later, she contradicted herself, according to an LA Times article published months before she won her first term as DA. She blamed the contradiction on low blood sugar that caused her to be confused. The Association of Deputy District Attorneys did not endorse Lacey that year.

But, she gained trust within the department by winning cases, and when, Cooley appointed her deputy DA in 2011, everyone knew she was fated to be his chosen successor. Lacey moved to LA County (she was living in Ventura County), and then Cooley announced his retirement. There was certainly a sense that Cooley was grooming Lacey to carry on his legacy, according to Joseph Iniguez, an assistant DA in the office who is also challenging Lacey in her upcoming election. Cooley said he believed she was the best person to carry on his legacy in the office and, in a 2012 LA Times article, credited her as a “great collaborator.”

Lacey faced a crowded field of five competitors at the primary level. (This sort of primary is a non-partisan contest to winnow the field. Lacey is a registered Democrat.) One primary opponent, then-Los Angeles City Attorney Carmen Trutanich, was favored to win and carried the governor’s and then-LA Sheriff Lee Baca’s endorsements in addition to over $1 million very early on in campaign donations. In a campaign debate, one of Lacey’s opponents, Alan Jackson, who prosecuted Phil Spector, accused her of being “out of touch” and lacking his courtroom experience. (Lacey, for her part, called Jackson “naive.”) Jackson, a Republican, was running to the right, and Lacey was then seen as “softer.” Jackson went on to become a high-profile defense attorney who recently represented the actor Kevin Spacey.

Lacey touted her support for Cooley’s moderately progressive ideas and his office’s policies, mainly through alternative courts: “My ideas are to take the lower-level offenders and put them on probation through alternative sentencing court. And that is really the wave of the future with regard to defendants who are suffering from drug addiction, alcohol addiction or mental illness who commit non-serious, non-violent felonies.” She also emphasized building up units to focus on computer crimes, closing rape law loopholes, and improving hate crime prosecutions.

During her campaign, Lacey emphasized her Los Angeles roots and her background as the daughter of a woman who came to Los Angeles from Georgia as a teen. When she was 21, she told Seventeen magazine (as part of a series on 13 young women): “I’ve seen so many black people cheated by tradesmen or intimidated by the police because they have no knowledge of their legal rights. I’d like to help change that.”

Lacey easily won the election by a wide margin with the support of Cooley as well as the endorsement of the LA Times and glittery national attention. Sean Combs tweeted, “Congrats to Jackie Lacey who became the first woman and African American to be elected district attorney of Los Angeles. LETS GO! POWERFUL!”

When she was elected, Lacey took over the largest district attorney’s office in the nation in a county that sends more people to state prison than any other in California. Lacey supervises almost 1,000 attorneys, 300 investigators, and 800 staff members. By comparison, New York City, with a population of over 8 million, has one district attorney for every borough; Los Angeles just has one for the whole county, which consists of 10 million people. The scale of the department immediately made Lacey a powerful figure as criminal justice reform became a prominent issue nationwide, and especially in California.

But Lacey has largely disappointed those who looked to the new, Black, female and Democratic district attorney to enact change. And, over time, once progressive prosecution ideas have become mainstream and Lacey seems woefully behind, in the model of the same tough-on-crime DA that residents had experienced for decades. Lex Steppling, the director of campaigns and policy for Dignity and Power Now, described Lacey as “a Black woman who claimed her roots openly and publicly, but has carried on the same racist, deadly legacy that preceded her.”

Lacey entered office during the first years of realignment, which reduced the California prison population by transferring supervision of low-level offenders to the county—those who had committed nonviolent, non-sexual, non-serious offenses. During her campaign, she stayed vague on realignment, telling the LA Times that it was “a terrible mistake” as well as “an opportunity.” When realignment didn’t result in a crime wave, she acknowledged that but maintained that there was a “public safety” concern. In an email to The Appeal, Lacey said, “I have supported and implemented criminal justice reform throughout my career as a prosecutor.”

She supported a 2013 change to her office policy, praised by the ACLU, which required prosecutors to disclose all impeachment evidence for law enforcement to the defense. But when activists pushed her for more disclosures, her office remained silent. She said she supported split-sentencing, which allows people to serve part of their sentence on supervision rather than jail, but was very slow to put it into effect. Only after San Francisco implemented an algorithm that would expunge marijuana convictions did Lacey join, too.

According to Black Lives Matter activists, Lacey hasn’t taken the steps to address the racial disparity in the system. She hasn’t supported a “Do Not Call” list that is meant to keep corrupt police officers off the witness stand. She is in the best position, activists say, to help regulate some of the worst excesses of the LAPD, a law enforcement agency with a long history of oppressing communities of color, but hasn’t done so. And Melina Abdullah, an organizer for Black Lives Matter Los Angeles and a professor at California State University, Los Angeles, told The Appeal in a phone interview that Lacey today is no longer the Lacey from Crenshaw: “She’s not grounded in the Black community now. … A lot of Black folks are awake to who she is.”

Steppling agreed that Lacey’s office lacks transparency, and added that the office has shown “zero interest in engaging the community.” Laurie Levenson, a law professor at Loyola Law School and former AUSA, concurred: “I think there’s a general need to open up the office, change the culture, make it understood to people in the community that all ranks can be heard.”

Abdullah says that Lacey’s failure to support progressive legislation is one of the biggest indictments against her as a leader. Lacey opposed Proposition 47, which shifted more incarcerated people away from jails. (“I can’t say I agree with Proposition 47,” she told the LA Times in 2014.) She opposed ending cash bail and has taken no steps toward reducing the city’s high incarceration rate and racial disparity in incarceration. She also opposed Proposition 57 and marijuana legalization, measures that easily passed with Los Angeles voters. She opposed changes to the felony murder law passed last year, even filing motions in court arguing that the statute was unconstitutional. (In July, California Attorney General Xavier Becerra filed a brief that the statute was constitutional.)

Then there’s the death penalty. In 2012, California voters had a provision to eliminate capital punishment on the ballot, Proposition 34. Lacey supported the death penalty (as did almost all of her opponents). The provision did not pass. In 2016, another provision made the ballot. It also failed, but was overwhelmingly popular in Los Angeles.

Yet, Lacey has continued to seek the death penalty in some cases, despite Governor Gavin Newsom’s moratorium on capital punishment. According to a recently released ACLU report, Lacey has sent 22 people to death row since she became DA in 2012, the highest in absolute numbers of any other jurisdiction. All are people of color. At least eight defendants were represented by counsel who had previously or subsequently been found guilty of misconduct.

Advocates focused on Lacey’s use of the death penalty as an especially disturbing example of how prosecutorial discretion perpetuates discrimination in the criminal legal system. In an email to The Appeal, Lacey said, “California voters have twice failed to abolish the death penalty.”

Levenson, however, believes that the ACLU report “didn’t tell the whole story.” She explained, “The big issue is not an individual issue. It’s the overall culture.” She described the longtime culture of the office as the “old-fashioned cowboy approach … hard core, law and order, not open to a different approach. Not collaborative.”

At the same time, Lacey has not yet prosecuted Los Angeles notables accused of corruption and other crimes, like the Church of Scientology and the producer Harvey Weinstein, despite the formation of a task force to look into these cases. Her office didn’t charge billionaire Ed Buck for two fatal overdoses that occurred in his West Hollywood apartment (her office ultimately charged him for a third, non-fatal overdose in September), arguing recently that the Los Angeles sheriff’s department bungled the investigation. She didn’t prosecute a California Highway Patrol officer who repeatedly punched a homeless woman in July 2014. (The highway patrol settled with the family for $1.5 million.). And questions have come up about her campaign contributions, which have included the bail bonds industry, police unions, and people facing felony charges from her office.

Now, as Lacey enters the race for a third term, she faces opposition from activists. After she declined to prosecute the officer who killed Glenn, activists held an early-morning protest on Lacey’s birthday in October 2018, projecting the words “Jackie Lacey Must Go” on her garage door. They continue to protest outside Lacey’s downtown office every week. Abdullah told The Appeal that activists tried unsuccessfully to get Lacey to attend a town hall meeting: “We tried to engage her, and she reneged on a community meeting.”

She is also facing a slew of challengers in the 2020 race. Unlike the 2012 election, most of these candidates are swinging further left, appealing to those who think Lacey should be enacting more reforms. Perhaps in response to this political pressure, in October, Lacey abandoned her opposition to a law that protected some drug offenders in diversion from deportation. The New York Times has already called the 2020 election “the most important district attorney’s race in America.”

Two current assistant DAs are running in addition to George Gascón who, before becoming the DA of San Francisco, served as the assistant chief under William Bratton when he was the chief of the LAPD. Advocates quoted in the New York Times discuss Gascón’s record for implementing new data-driven solutions and attempts to reduce racial disparity in prosecutions. And, there has been grassroots encouragement for Gascón to run, including an aptly named Twitter account.

But, Gascón has also failed to prosecute officers for high-profile killings. It wasn’t long ago that Gascón faced angry protesters who threw rotten fruit at his apartment door. On the other hand, he championed Assembly Bill 392, now California law, which changed the standard for law enforcement’s use of deadly force to “necessary.” Lacey publicly opposed the law.

Joseph Iniguez, a deputy district attorney under Lacey, is running as the upstart reform candidate. Iniguez came to LA after Lacey won the election because he was eager to work for what he hoped would be a progressive boss. In a phone interview, he said, “She deserves the utmost respect for all of the barriers she’s broken. She doesn’t deserve a pass.” Richard Ceballos, a deputy DA in Lacey’s office, has announced his candidacy as well and is running as “smart on crime,” arguing also that the DA’s office needs to be more progressive.

No matter who is in office, there will be challenges to reform. Levenson believes that Lacey’s attempts to change the office are stymied by others in her office. The deputy district attorneys are protected by their union, which makes firing and demoting people more difficult. In contrast, Abdullah argues that it’s not the deputies hampering Lacey’s reform efforts; it’s that Lacey is “more beholden to police associations who heavily endorse her and give the maximum allowable contributions.”

Abdullah had little patience for letting Lacey off the hook: “It would be relatively easy to build a better reputation than she has,” she told The Appeal. “I think you couldn’t really be much worse.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled the surname of a law professor at Loyola Law School. She is Laurie Levenson, not Laurie Levinson.