How Criminal Justice Reformers Should Confront Justice Kennedy’s Retirement

First, look to local prosecutor elections.

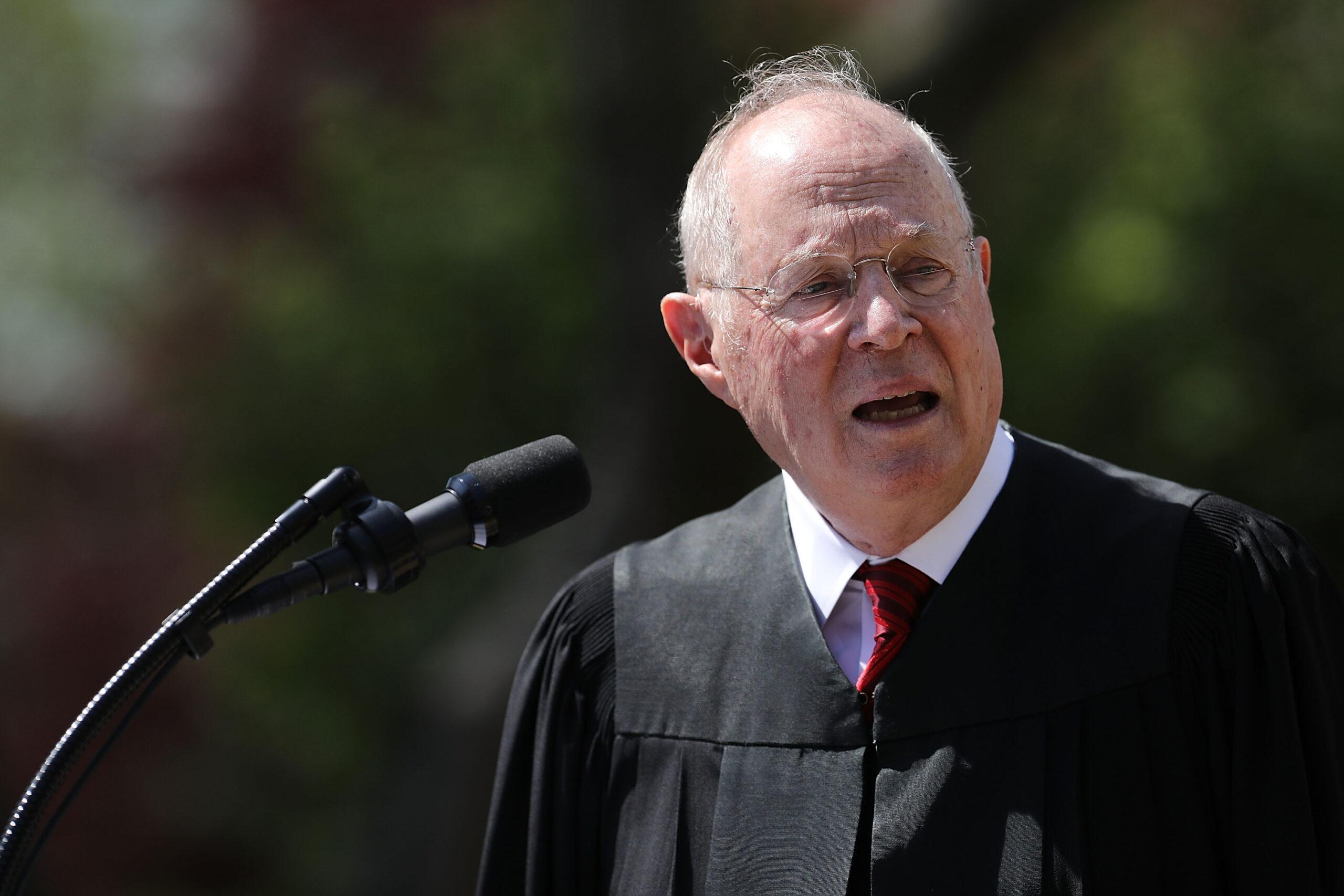

The retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy from the Supreme Court this week has left advocates of civil liberties in great despair. Kennedy, a moderate conservative who was often the court’s swing vote, will most likely be replaced by a staunch conservative. Abortion rights, voting rights, affordable healthcare, and many other issues that affect the daily lives of Americans now hang in the balance.

What will this sea change mean for the future of the criminal justice system? It is hard to tell. The system is in dire need of reform: Too many people are incarcerated for far too long; people of color are treated worse than their white counterparts; and the quality of justice one receives depends far too often on one’s income. But even while Kennedy sat on the bench, the Supreme Court has never provided a remedy to these problems. In fact, one might argue that the Court has been part of the problem.

The Supreme Court gave us Terry v. Ohio, a case that permitted cops to stop and frisk individuals based on “reasonable suspicion”—a standard even lower than the probable cause required for an arrest. Many cops stop, search and harass individuals without even meeting that low standard. Terry laid the groundwork for racial profiling, and the Court’s decision in Whren v. United States left no doubt that the Supreme Court would not provide a remedy for this practice. The Fourth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures, but the Supreme Court has created so many exceptions to the warrant requirement that the exceptions devour the rule. Cases like Graham v. Connor, Scott v. Harris, and most recently, Kisela v. Hughes, give cops permission to use excessive and deadly force in far too many circumstances. This is all settled law. With another conservative justice on the Court, it could get worse.

That is why it is so important, now more than ever, that we pay attention to the election of prosecutors at the state and local level. Over 99 percent of all criminal cases are resolved in state court, and the most powerful official in the system is the prosecutor. Prosecutors alone decide whether to bring criminal charges and what those charges should be. They decide whether to offer a plea bargain and what the plea should be. The charging and plea-bargaining decisions effectively control the system and even predetermine the outcome in most cases, especially when one considers the fact that 95 percent of all criminal cases that result in convictions are resolved with a guilty plea. The power and discretion of prosecutors is almost unlimited, and unfortunately most prosecutors have pursued tough-on-crime agendas that exacerbate the problems in our criminal justice system, like mass incarceration and racial disparities.

The good news is that prosecutors can use their power and discretion to reform the system—if they have the will to do so. That is why we must work to elect progressive prosecutors. Progressive prosecutors can choose not to bring charges for minor offenses and can divert nonviolent cases out of the system. Progressive prosecutors can oppose cash bail and propose alternatives to incarceration. Even with a Supreme Court hostile to criminal justice reform, progressive prosecutors can make a difference. They can dismiss cases based on racial profiling and unconstitutional searches, and they can prosecute cops who use excessive force. But they will only do this if we demand it.

Recently elected progressive prosecutors are demonstrating the power of their offices to create change. Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, who took office this year, issued a memo to the prosecutors in his office directing them to decline certain charges, divert more cases, and seek lower sentences. In Cook County, home of Chicago, State’s Attorney Kim Foxx, has made significant progress toward bail reform, increased transparency, and making fairer charging decisions since her election in 2016. Houston District Attorney Kim Ogg, also elected in 2016, has declined prosecution of minor marijuana offenses and implemented bail reform.

Even as the Supreme Court moves further to the right, we can fix our broken criminal justice system if we elect prosecutors committed to meaningful reform and hold them accountable. No matter who is on the Court, prosecutors can use their power and discretion to reduce the incarceration rate, eliminate racial disparities, and create a criminal justice system that is fair and just for all. We must demand that they do so.

Clarification: This article cited Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg’s commitment to bail reform. Shortly after this piece was published, a leaked email from Ogg revealed that her office is continuing to request high bond amounts for minor crimes, a policy inconsistent with a commitment to serious bail reform in the opinion of the authors.